Fads, FOMO, and Financial Ruin

How to Be Smarter Than Sir Isaac Newton

No one wanted to be caught hanging out at Jonathan’s Coffee House.

The unassuming shop – a hole in the wall in London’s seedy Exchange Alley – was frequented by pickpockets and ladies of “easy virtue.”

Even worse… it was also a den of stock traders.

It was the early 1700s, years before London launched an official stock exchange. Commodities traded at the posh Royal Exchange, but stocks, and the “stock jobbers” who hawked them, were considered too uncouth for the classy digs. So stock traders congregated at Jonathan’s, swilled black coffee, and chalked prices on the wall, while couriers ran back and forth from the nearby post office with the latest news.

In the less-than-reputable Exchange Alley, you minded your own business. So no one asked too many questions about the mysterious “Mr. Newton” who showed up one day.

Or suggested that he maybe shouldn’t invest his entire fortune in the shares of South Sea Company.

But Sir Isaac Newton literally discovered the law of gravity. He wasn’t likely to take anyone’s advice but his own.

In 1719, the brilliant physicist, mathematician, and economist was pushing 80. He was also rich… and bored with his cushy government position as “Master of the Mint,” a largely honorary post he’d been awarded thanks to his encyclopedic knowledge of finance and currency.

Tired of micromanaging the depth of engravings on the gold guinea, Sir Isaac likely wandered down to Jonathan’s Coffee House one afternoon… and got sucked into one of the biggest stock market bubbles of all time.

The Physicist and the Ponzi Scheme

The South Sea Company – whose shares Newton bought – was a British joint-stock company (an early version of an LLC) founded in 1711 by an Act of Parliament. It primarily facilitated the slave trade between Africa and Spain’s western colonies… and, later, branched out into other schemes to reduce the British government’s sizeable debt.

After a few years of lackluster performance, King George took over as the company’s governor, which sent the shares soaring.

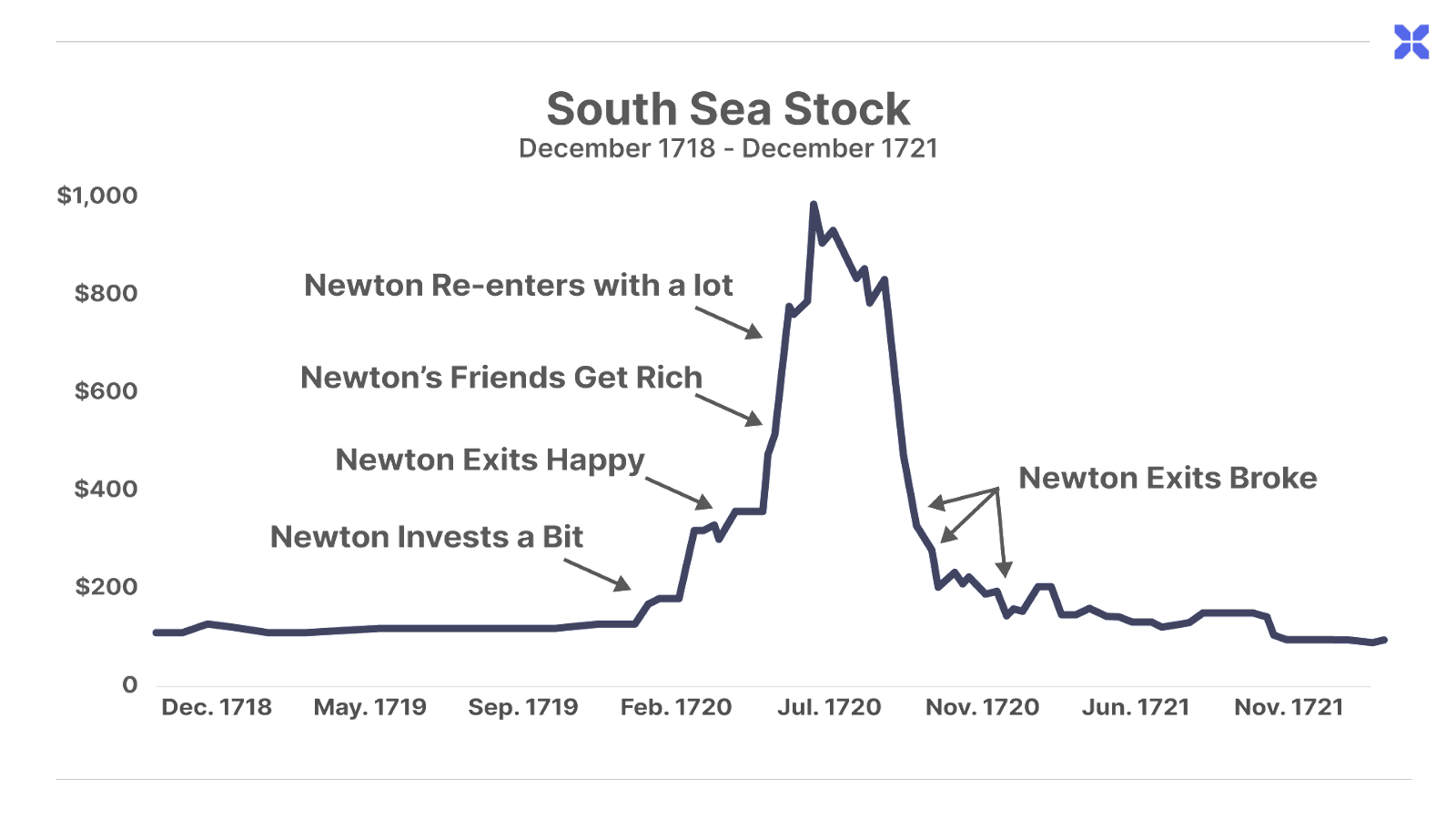

Profits couldn’t justify these valuations, but try telling that to the patrons of Jonathan’s Coffee House. By late 1719, Sir Isaac Newton had succumbed to the mania and accumulated a South Sea position valued at £13,000, equivalent to $2.5 million in today’s money. After buying in under £200 per share, he began selling the stock at £400 per share.

He should have stopped while he was ahead. But instead, he got caught up in phase two of the South Sea bubble: the Ponzi scheme.

In 1720, the South Sea Company pitched a program to convert British debt into South Sea shares. The scheme sparked an even wider mania as bribes flowed through Parliament (ensuring its acceptance). Company owners encouraged others to continue fueling the speculative bubble (and the Ponzi) as it proposed using the sale of new shares to pay down the £32 million in British government debt that had accumulated.

Demand kept rising from February 1720 to April 1720, and South Sea share prices roughly doubled.

That year, Parliament member Archibald Hutcheson published warning pamphlets arguing that South Sea stock was worth no more than £200. Newton should have listened. But as the stock moved past £500, the Master of the Mint got greedy.

He bought back in… at almost double the price he received as a seller months prior.

Weeks after his new purchase, the stock price collapsed from over £950 to under £200 and dropped further over the following two years.

By December 1720, Newton lost today’s equivalent of millions. He’d discovered gravity decades earlier when an apple fell in his garden – but now, he’d learned painfully that the same principles held true in the stock market.

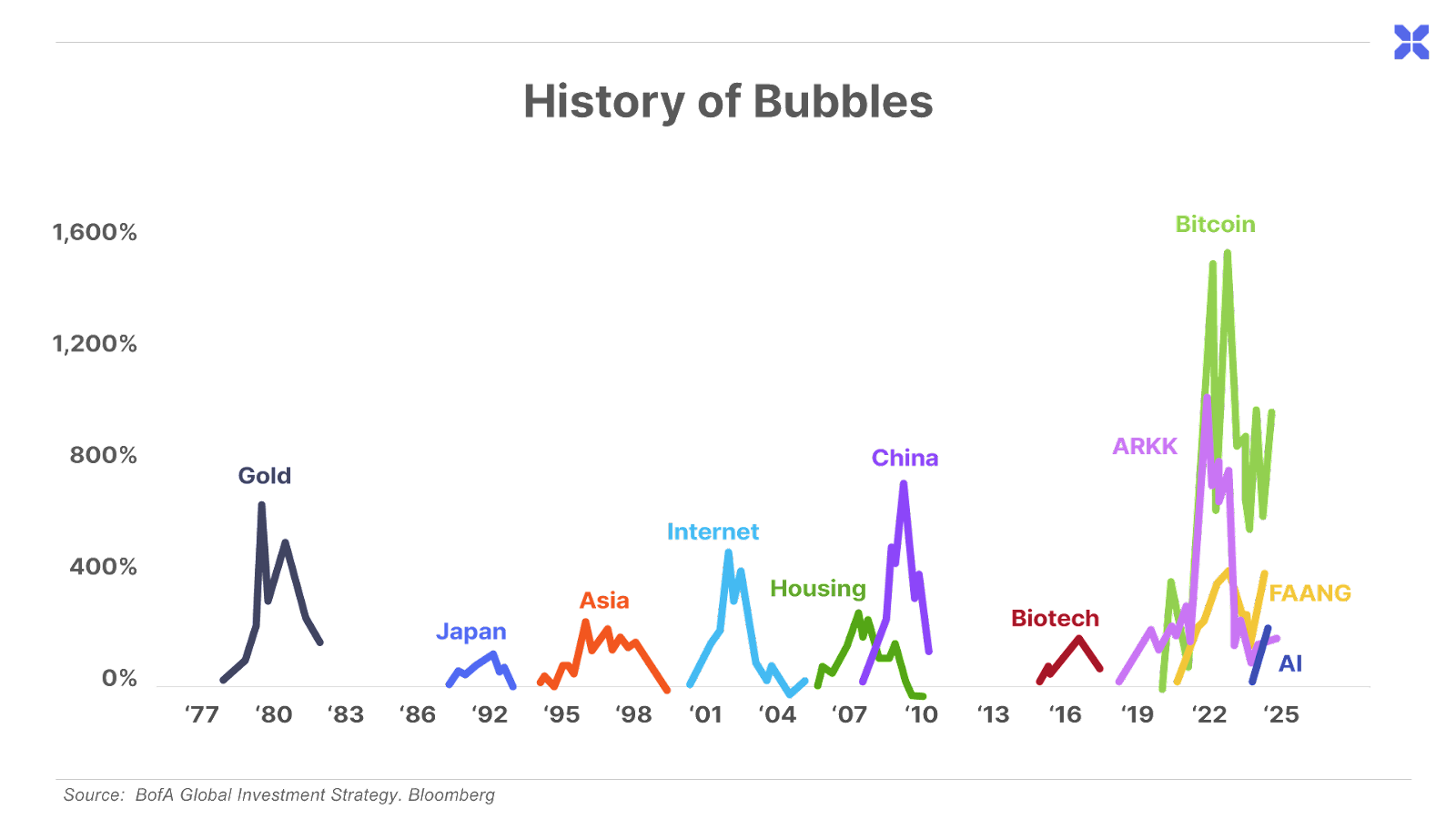

Despite his education and preternatural understanding of risk and numbers, Newton fell for a classic economic bubble – just like countless other speculators over the centuries. And we’ll keep making those errors today… unless we understand how fads work and how to avoid them.

What Isaac Newton Missed

An investment fad is a short-term financial trend that quickly gains popularity and interest among investors – but typically lacks long-term viability or strong underlying fundamentals.

You don’t need a deep understanding of finance – or physics, or astronomy – to spot fads. (As Newton regretfully acknowledged after the South Sea disaster: “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”) You simply need a strong mix of skepticism, market awareness – and knowledge of a few bright-red flags:

- Red Flag #1: CNBC or other media outlets push the new trend. Media-sponsored events and “investment conferences” typically encourage investors to invest large sums immediately, pushing a combination of FOMO (fear of missing out) and promises of high, fast returns.

- Red Flag #2: The returns don’t align with historically average market returns. Fads typically lack fundamentals, strong business models, revenue streams, and developed markets. Instead, they rely more on hype than substance.

- Red Flag #3: The “peanut gallery” is buzzing. Watch to see if people with a shallow knowledge of investing get excited about an opportunity. If your cousin – who can’t balance a checkbook – starts trading Dogecoin on his cell phone, that’s a bad sign.

- Red Flag #4: The business operators make bad decisions. In addition to the investment, you must look at the people who are operating the companies… and see if they have a weak track record or a history of failed ventures in various businesses. A person who was working in cannabis in 2019, angel investing in 2020, jumped to blockchain in 2021, and then ran a non-fungible-token (“NFT”) company in 2022 probably isn’t your ideal CEO.

- Red Flag #5: The regulators are cautious. If you can’t spot fads independently, regulatory agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) or Commodity Futures Trading Commission occasionally issue alerts about potential investment scams or fads.

As a masterclass in fads, consider one-time wunderkind investment manager Cathie Wood, who has notoriously invested in unprofitable companies with terrible fundamentals. They usually do great… for a while… until they collapse. Wood’s Ark Innovation Fund (ARKK) portfolio consists of tech wunderkinds like Coinbase (COIN), Roku (ROKU), and Zoom Video Communications (ZM).

Wood argues that investors need to “wait five years” for Ark’s investment to pay off – yet continue to burn through money in overhyped industries that still lack developed markets and companies that have competitive advantages in those spaces.

Let’s look at several prominent fads of the last decade and see how they fit into our framework… and where they are now.

Digital Junk

In what could be the largest bubble in the last 50 years, junk cryptocurrencies (non-Bitcoin or Ethereum) and NFTs reigned over other recent fads like Cathie Wood’s fund or the Magnificent Seven or FAANG stocks.

NFTs are unique digital assets that are verified using blockchain technology. The developers say they ensure the authenticity of digital artwork or collectibles.

Three years ago, it was impossible to escape the hype of the cryptocurrency and NFT market – including the media’s godlike praise for fraud extraordinaire Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX.

The NFT craze peaked when digital marketplace Opensea surpassed $10 billion in all-time trading volume in November 2021. Media speculation fueled expectations of massive growth in the NFT space, especially with large tech firms like Facebook (now Meta Platforms) angling toward the Metaverse (another fad that hasn’t reached its potential).

The craze suggested widespread disruption of mortgage contracts, concert tickets, and other forms of contract law. There was even speculation on individual NFTs, including the purchase of the first Tweet ever (Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s) for $2.9 million.

Today, most NFTs are worth a fraction (at best) of their speculative values just three years ago. A few years later, the Dorsey NFT received a bid of just $4.

The best equity representation of this fad was the collapse of the Defiance Digital Revolution ETF (NFTZ). The exchange-traded fund (ETF) tracked the performance of various companies expected to benefit from adopting blockchain, NFTs, and, ultimately, the Metaverse.

Following its inception in late 2021 (the height of this bubble), the ETF cratered by more than 70% before shutting down in February 2023. From Dogecoin to cryptocurrencies designed to pay for dental work, the space has experienced a dramatic decline in recent years. And all the money remaining has spilled into the last two major projects standing: Bitcoin and Ethereum.

We anticipate that Bitcoin will continue to do well as investors push into “digital gold” and institutions move into the space via spot ETFs. Bitcoin is the one consistent cryptocurrency that isn’t built around fad projects.

The Cannabis High Is Over

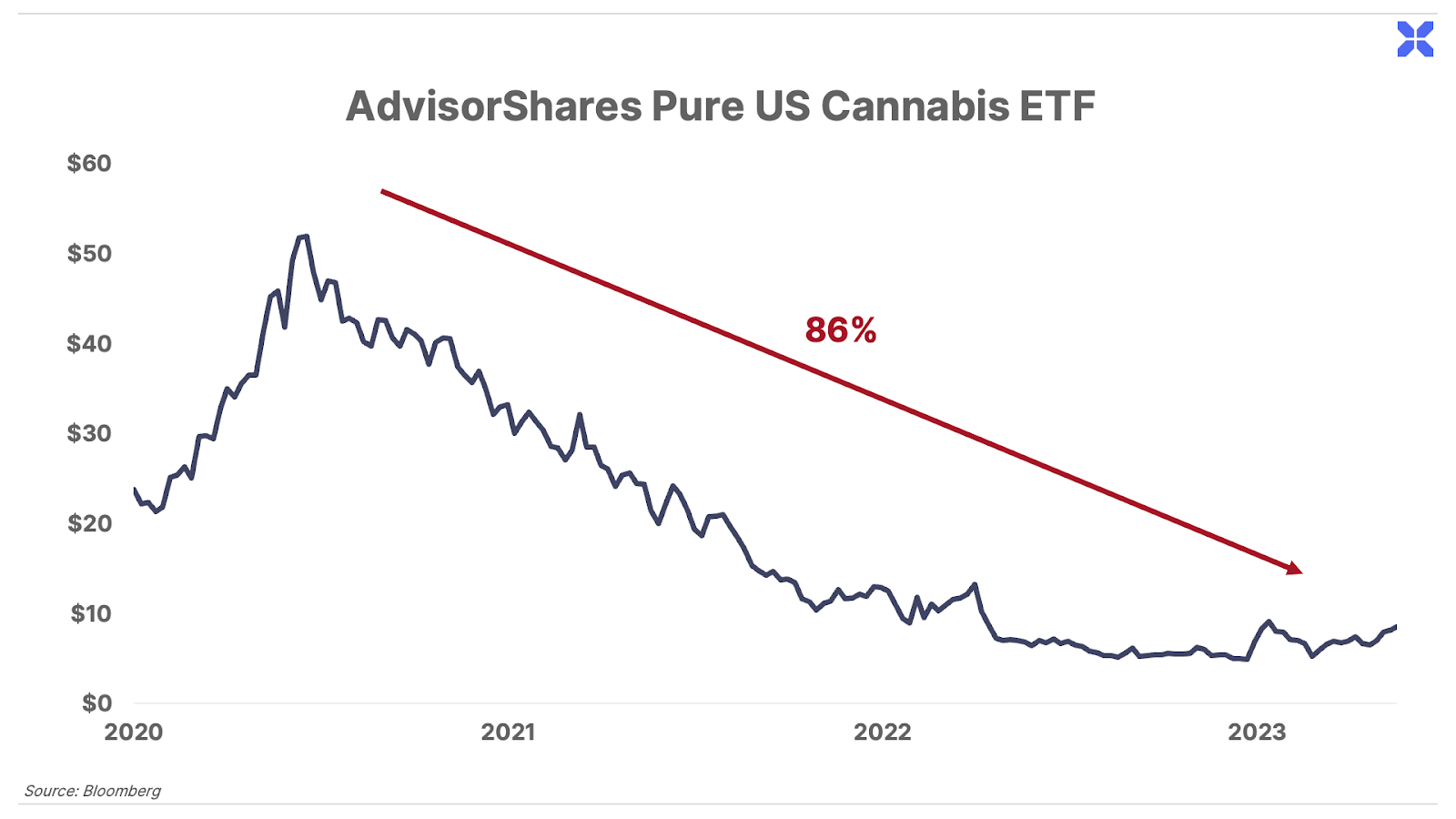

Cannabis has been another speculative fad in the last five years.

The media helped fuel this craze by over-sensationalizing minor policy shifts, while pundits encouraged investors to pour billions into the sector.

Investors speculated on catalysts like widespread legalization of medicinal and recreational cannabis at the state level. Toronto-based cannabis company Canopy Growth (WEED.TO) hit a market capitalization above $40 billion, while stocks like Scotts Miracle-Gro (SMG) – a fertilizer company – surged from $100 per share to nearly $250 in two years.

But years later, marijuana remains a Schedule I drug, companies still can’t bring cannabis across state lines, and questions still exist about the banking sector’s future role in providing services to cannabis operators. Scotts Miracle-Gro is trading today at $57 per share, while the investors lost more than $39 billion on Canopy Growth from its top in February 2021 (at C$547 per share) to the C$6.00 price it traded on January 18.

And, since its inception, the AdvisorShares Pure U.S. Cannabis ETF (MSOS) has declined by 68%, while it’s dropped roughly 86% from its all-time high in February 2021.

More Bad Apples Fall

The past few years have been a bumper crop for fads, as the Federal Reserve’s massive quantitative easing and trillions in Congressional stimulus gave speculators all the fiscal grease required to keep the markets running at outlandish valuations.

The electric-vehicle (“EV”) mania has fizzled, with stocks like ChargePoint (CHPT) and Rivian Automotive (RIVN) off 96% and 90% from their 2020 and 2021 respective highs. Despite all the government mandates, consumers still don’t want EVs, and the sector is crashing.

Work-from-home stocks like DocuSign (DOCU) and Zoom Video Communications (ZM) have also collapsed 80% and 88%, respectively, from their speculative highs after the COVID-19 bubble. The short-term thinking argued that companies would allow their workers to stay home in their sweatpants and be unproductive. But companies have sobered up, and put frameworks in place to get workers back to the office – or, in Porter & Co.’s case, the barn.

Finally, the wave of special purpose acquisitions corporations (SPACs) has fueled dramatic losses, bankruptcies, and busts in recent years. In 2020, the SPAC craze started with private companies merging with shell companies to bring those companies public. This included names like sports-gambling business DraftKings (DKNG) and EV maker Lucid Group (LCID). These companies were largely venture-capital-level investments with sky-high valuations in developing industries. Speculators went crazy bidding up these stocks. DraftKings surged more than 600%, before crashing back to Earth a year later.

In 2023 alone, 21 SPACs went bankrupt, according to Bloomberg. All told, those bankruptcies wiped out $46 billion in shareholder equity from their peak market capitalizations.

These aren’t the last fads or bubbles of our lifetime.

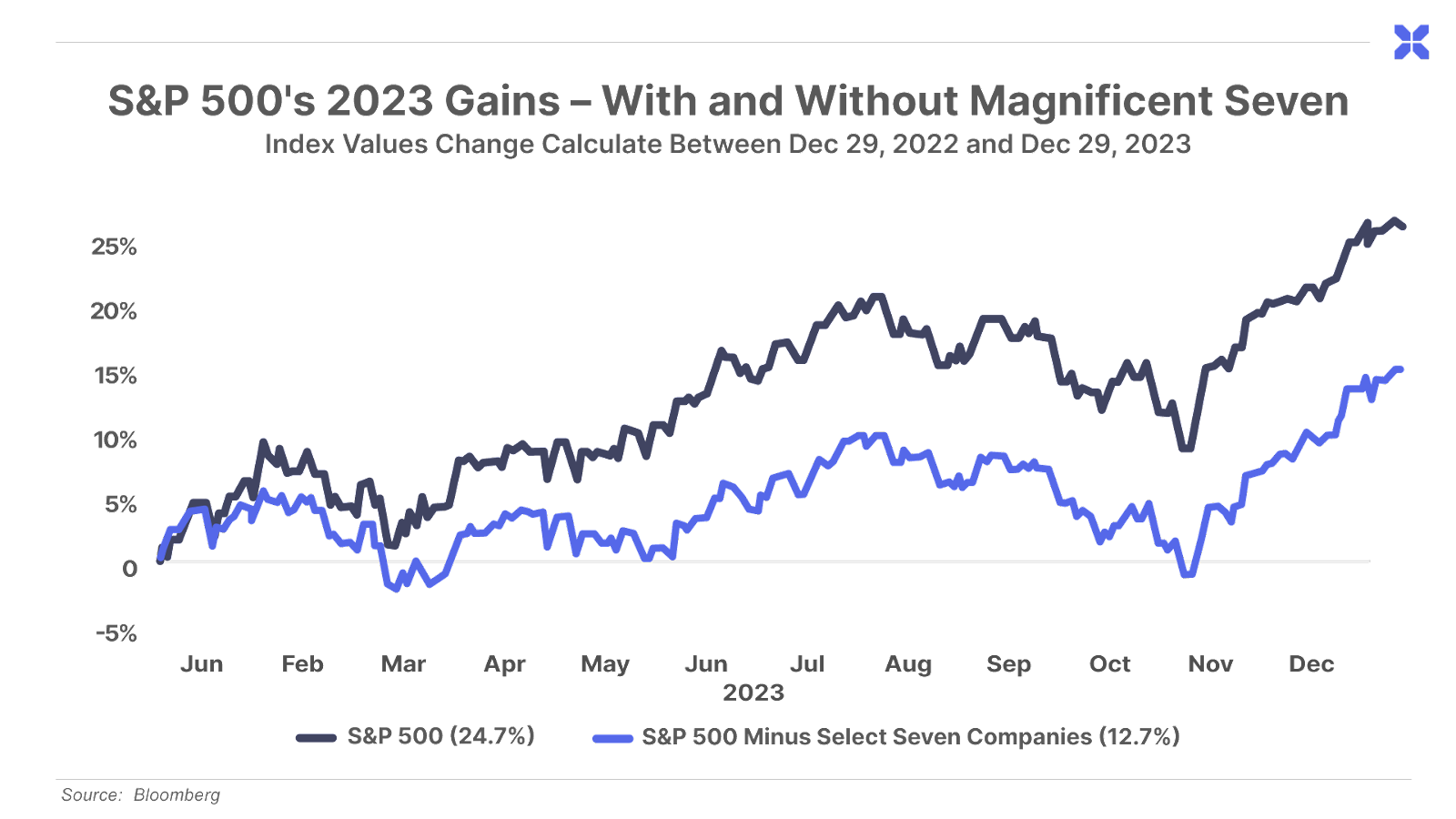

In fact, we are still watching the Magnificent Seven rally of the last year that has pushed the largest S&P 500 stocks by market capitalization to unreasonable valuations. And we expect this will eventually pop. As we recently explained, companies like Tesla (TSLA) and Microsoft (MSFT) are now trading at 69 times and 37 times earnings, respectively. The companies responsible for the S&P 500’s 2023 performance are trading at bubble-level metrics.

In fact, the S&P 500 finished 2023 up 24.7%, but taking out the performance of these seven high-flying stocks, the index rose only 12.7%

Avoid Fads, Focus on the Long Term

The adage goes that if it’s too good to be true, it likely is.

While the hype of these “disruptive” sectors and speculative investments creates profits for some early investors, the downside risk is much larger than the short-term outcomes.

Here at Porter & Co., we refuse to chase fads. We focus on great companies with low debt, tangible assets, and strong capital efficiency – ones that return the maximum amount of cash possible to shareholders over a long period of years. You can see our capital efficient watchlist here.

If you’d like to get access to our latest recommendations, click here to join our paid version of The Big Secret on Wall Street and get access to our biweekly recommendations and portfolio of long-term, viable investment ideas.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team, you can get acquainted with us here. You can follow me (Porter) here: @porterstansb.