A Third-Generation Compounding Machine

Better Than Buffett And Under The Radar

| Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at: [email protected]. Paid subscribers can also access this issue as a PDF on the “Issues & Updates” page here. |

In 1983, a silent killer infiltrated the Jackson County Courthouse in Kansas City, Missouri.

Courthouse administrator Nancy Lopez never stood a chance.

The threat came from the construction crew working overhead Lopez’s office. For months, the demolition crew of U.S. Engineering unleashed a steady downpour of white flakes that covered every surface of Lopez’s office like a winter wonderland.

But unlike harmless snowflakes from the sky, these white flakes contained millions of microscopic asbestos fibers. In the 1980s, asbestos was a commonly-used construction material for flooring and insulation. But the same properties that make asbestos a prized construction material for its durability and heat resistance also allow these molecules to wreak havoc inside the human body.

For months, as the construction crew ripped apart the flooring above Lopez’s office, a torrent of tiny asbestos fibers made their way into her respiratory system. These deadly fibers remained lodged inside Lopez’s lungs for the next 29 years, causing scarring, inflammation, and, ultimately, mesothelioma – an aggressive, incurable form of cancer that attacks the lining of the lungs. After her diagnosis in 2009, the 54-year old Lopez sued U.S. Engineering for gross negligence and punitive damages.

Lopez died in 2010 before the suit was resolved. But in 2011, her family received a $10 million settlement – the largest amount ever for an asbestos suit in the state of Kansas.

Included in the group of insurers footing the bill for the record payout was National Indemnity Company (“NICO”), a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (BRK). Lopez’s suit was the beginning of an avalanche of record-setting asbestos liability claims that would ultimately result in a multibillion-dollar underwriting loss inside Berkshire’s reinsurance segment and the bankruptcy of another subsidiary company.

Buffett Becomes The Asbestos Clean-Up King

Buffett’s asbestos fascination began in the early 2000s, during the industry-wide distress of insurers being crushed by exploding asbestos liabilities. In the 1980s and 1990s, asbestos lawsuits skyrocketed as the public (and class-action lawyers) became aware of a growing list of companies that released deadly, asbestos-laden products onto the public. The number of asbestos lawsuits tripled in the 1990s, and by the year 2000 over half a million suits were filed each year.

As product manufacturers and construction companies began going bankrupt, the fallout spread into the insurance companies that wrote policies against asbestos liabilities. Before long, even titans of the insurance industry like American International Group (AIG) and Lloyd’s of London were crushed as claims costs spiraled out of control.

Warren Buffett spotted an opportunity. Specifically, he saw a chance to acquire cheap insurance float – the upfront cash insurers collect from policyholders, which is set aside to pay out future claims. In the period between collecting the cash and paying out claims that money can be invested to earn a return.

In the mid-2000s, Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway’s insurance guru Ajit Jain reached out to insurance companies facing runaway asbestos liabilities to offer reinsurance deals (insurance for other insurance companies). In simplified terms, Berkshire would take a portion of the asbestos liabilities off the insurers hands. In exchange, the insurers would transfer an agreed upon amount of float to Berkshire, which it could then invest.

The trick was figuring out what ratio of liabilities to float to offer. Buffett and Jain crunched the numbers, including the estimated costs of future asbestos claims and the timetable over which they would occur. They then compared that cost schedule against the estimated returns Berkshire could earn from investing the float along the way. Their math said Berkshire could make money by taking on roughly $2 in asbestos liability for every $1 of float acquired.

The first major deal Berkshire struck was in 2006 with a Lloyd’s of London subsidiary called Equitas. Buffett described the terms of the deal in Berkshire’s 2006 annual shareholder letter:

We said – and I’m simplifying – that if Equitas would give us $7.12 billion in cash and securities (this is the float I spoke about), we would pay all of its future claims and expenses up to $13.9 billion. That amount was $5.7 billion above what Equitas had recently guessed its ultimate liabilities to be.”

This was the single largest deal of its kind in the history of the industry, and it was just the beginning. In a 2010 deal with CNA Financial, Berkshire took on another $4 billion in asbestos liabilities in exchange for $2 billion in float. The following year, AIG offloaded $3.5 billion in asbestos liabilities to Berkshire for $1.65 billion in float.

By 2013, Berkshire completed over two dozen similar reinsurance policies. That year, Jain noted in an email to a journalist that Berkshire had the “largest single exposure to asbestos and pollution claims of any insurer.” Even for a company of Berkshire’s size, which was generating about $10 billion in profits annually, this was a massive bet with tens of billions of dollars at stake.

Commenting on the risks involved, Buffett noted in Berkshire’s 2006 shareholder letter:

And how will Berkshire fare? That depends on how much ‘known’ claims will end up costing us, how many yet-to-be-presented claims will surface and what they will cost, how soon claim payments will be made and how much we earn on the cash we receive before it must be paid out. Ajit and I think the odds are in our favor.”

But one thing Buffett and Jain didn’t count on was just how sky-high the costs of these asbestos claims would ultimately become.

Buffett’s Asbestos Blunder

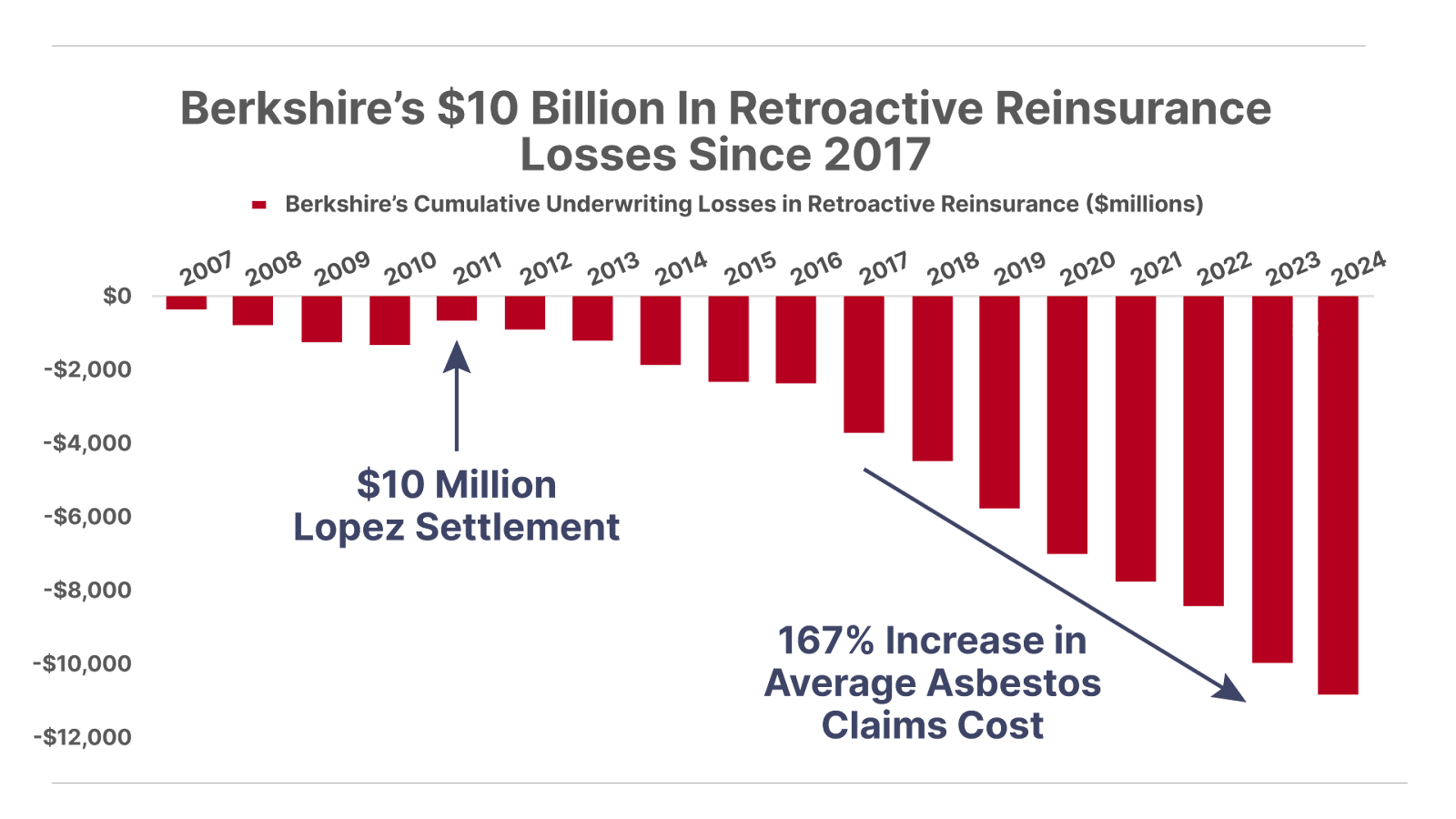

Just as Berkshire was inking the last of its multibillion-dollar asbestos reinsurance deals in the early 2010s, settlements like the $10 million payout to Nancy Lopez’s estate in 2011 started becoming the rule rather than the exception. This trend has only accelerated in the years since. From 2017 to 2023, the average settlement for asbestos liabilities claims among insurers rose by 167%.

And as the world’s largest asbestos liability insurer, Berkshire has felt the brunt of these runaway costs. The company includes the underwriting results from its asbestos reinsurance contracts in a segment called “retroactive reinsurance.” This refers to reinsurance contracts that provide liability coverage on policies previously written (as opposed to standard reinsurance contracts written for new policies).

Berkshire doesn’t necessarily need to earn an underwriting profit on these insurance policies. It only needs to avoid losing more money than it can earn on the float. However, if the underwriting losses balloon faster and larger than expected, the odds of earning a positive return from the float go way down.

With that in mind, take a look at the table below showing Berkshire’s cumulative underwriting profit/loss in retroactive insurance starting in 2007, the first full year after its landmark $14 billion asbestos deal with Lloyd’s in 2006. Note how the underwriting losses were contained at several hundred million for the first few years, but then began accumulating into a mountain of red ink starting in 2011 – the year of Nancy Lopez’s $10 million payout. The losses then accelerated starting in 2017, when asbestos claim costs increased by 167% over the next six years. The end result: Berkshire has now accumulated $10.8 billion in underwriting losses in its retroactive reinsurance segment since 2007:

We wonder whether Jain and Buffett forecast this level of underwriting losses during their asbestos-liabilities buying spree, and whether the returns on float have more than offset nearly $11 billion in underwriting losses. As one example, consider that Berkshire has paid out $3.7 billion in asbestos claims through its reinsurance policy with CNA Financial, a deal struck in August 2010. Berkshire received $2 billion in float in exchange for taking on these liabilities.

Using that example as a proxy for the rest of its retroactive reinsurance policies, we estimate that Berkshire needs to earn a consistent 12% return to avoid eroding the value of the float it acquired from these deals. While that’s not an impossible hurdle rate for one of the world’s greatest investors, it’s far from a layup investment with a wide margin of safety that has made Berkshire famous. And should asbestos claims continue surging higher over time, that hurdle rate will increase, raising the risk that Berkshire’s asbestos gambit backfires.

But the risks don’t stop at the insurance level.

The Texas Two Step

In 2007, Buffett spotted another source of asbestos-fueled float buried within a company called Whittaker, Clark & Daniels (“WCD”). WCD was a major supplier of talc for cosmetics companies L’Oréal, Maybelline, and Revlon, until it was discovered that its talc was laden with asbestos. Lawsuits landed the talc supplier in bankruptcy court in 2004, during which the company shuttered its manufacturing operations and established a cash reserve to pay out future claims against its asbestos liabilities.

In 2007, Berkshire bought WCD out of bankruptcy for an undisclosed sum. This gave Berkshire control of the company’s cash reserve, which it planned to invest and generate a return on while managing the asbestos-liability claims – effectively tapping into another source of float. The problem was, losing bankruptcy protection meant the liabilities Berkshire took on from WCD were open-ended (unlike the reinsurance deals described earlier, which contained liability limits).

By 2023, WCD’s claims liabilities had grown to hundreds of millions of dollars, and threatened to drain away the cash set aside to pay out the claims. In March 2023, a South Carolina jury awarded a crushing $29 million settlement against WCD for a single asbestos victim. With thousands of other claimants waiting in the wings, and WCD’s cash reserves running thin, Buffett threw in the towel.

Berkshire attempted to stem the bleeding at WCD by deploying a controversial legal maneuver known as the “Texas Two Step.” Step one involves re-incorporating a liability-laden subsidiary into a friendly jurisdiction (often Houston, hence the Texas Two Step designation), and step two is placing that subsidiary into bankruptcy. The net effect is that the assets of the parent company (in this case, Berkshire Hathaway) are shielded against the liabilities of the subsidiary through bankruptcy protection.

The problem for Berkshire is that the courts are pushing back against this practice. Pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) has spent the last several years attempting the same maneuver to limit its exposure to tens of billions in asbestos liabilities related to talc products. It created a subsidiary called Red River Talc, and tried and failed three separate times to place the subsidiary into bankruptcy. After the third and final attempt was rejected on March 31 by a federal judge in Houston, J&J’s management team announced it would give up on the bankruptcy plan.

The company will now be forced to litigate its asbestos claims through the court system, which opens the company up to the unlimited liability from over 90,000 individual claimants. With the new strategy opening the company up to liabilities in the tens of billions of dollars, J&J shares plunged 7% on the day of the ruling, its largest drop since March 2020.

Berkshire could face a similar, albeit less severe situation, if its attempts to resolve WCD’s asbestos claims through bankruptcy are rebuffed by the court system as well. So far, Berkshire has recorded a $490 million impairment charge on its WCD investment – a figure based on its current proposal to pay $535 million to the bankruptcy estate of WCD.

One attorney representing WCD’s talc claimants described the $535 million offer as a “smack in the face” to claimants. Lawyers representing WCD’s asbestos victims have appealed Berkshire’s bankruptcy proposal for WCD, which is subject to the approval of a New Jersey court. If the court follows the recent precedent of the Johnson & Johnson case and rules against the bankruptcy plan, Berkshire could be on the hook to litigate individual claims for thousands of asbestos victims – representing a potential liability that could run into the billions of dollars.

Of course, for a company the size of Berkshire Hathaway, even a multibillion-dollar liability is not an existential risk. But at the very least, we think investors should get a little more disclosure from the Oracle of Omaha on its ballooning asbestos liabilities. Berkshire has so far provided little disclosure on the WCD risks – not even mentioning the company by name when it reported the bankruptcy filing in its quarterly and annual filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Berkshire simply referred to a “certain non-insurance affiliate” when noting the $490 million impairment charge from WCD in its Q3 filing.

There’s also the ongoing potential for losses in Berkshire’s far larger asbestos bet in its retroactive reinsurance policies. While these liabilities are capped and thus known with certainty, that should provide little solace to investors. As of its latest 2024 annual report, Berkshire notes that the maximum loss of this segment will “not exceed $47 billion.”

Remember that number. It’s not the only ~$40 billion legal exposure Berkshire faces. Asbestos isn’t the only huge problem Berkshire’s been hiding.

Buffet The Investor: The Greatest of All Time

Buffett The Operator? Average At Best

Very few executives have been able to successfully build and manage a conglomerate.

Henry Singleton at Teledyne is a notable and outstanding exception.

It’s difficult to have a “circle of competence” that’s broad enough to fully understand, in a deep, visceral, and meaningful way the operating challenges of dozens of disparate businesses, much less dozens of disparate industries.

Where Buffett has been able to find great operators (Nebraska Furniture Mart, GEICO, Forest River) Berkshire has done extremely well.

But since the Global Financial Crisis, as the size and complexity of his whole-company acquisitions grew, Buffett has done shockingly poorly.

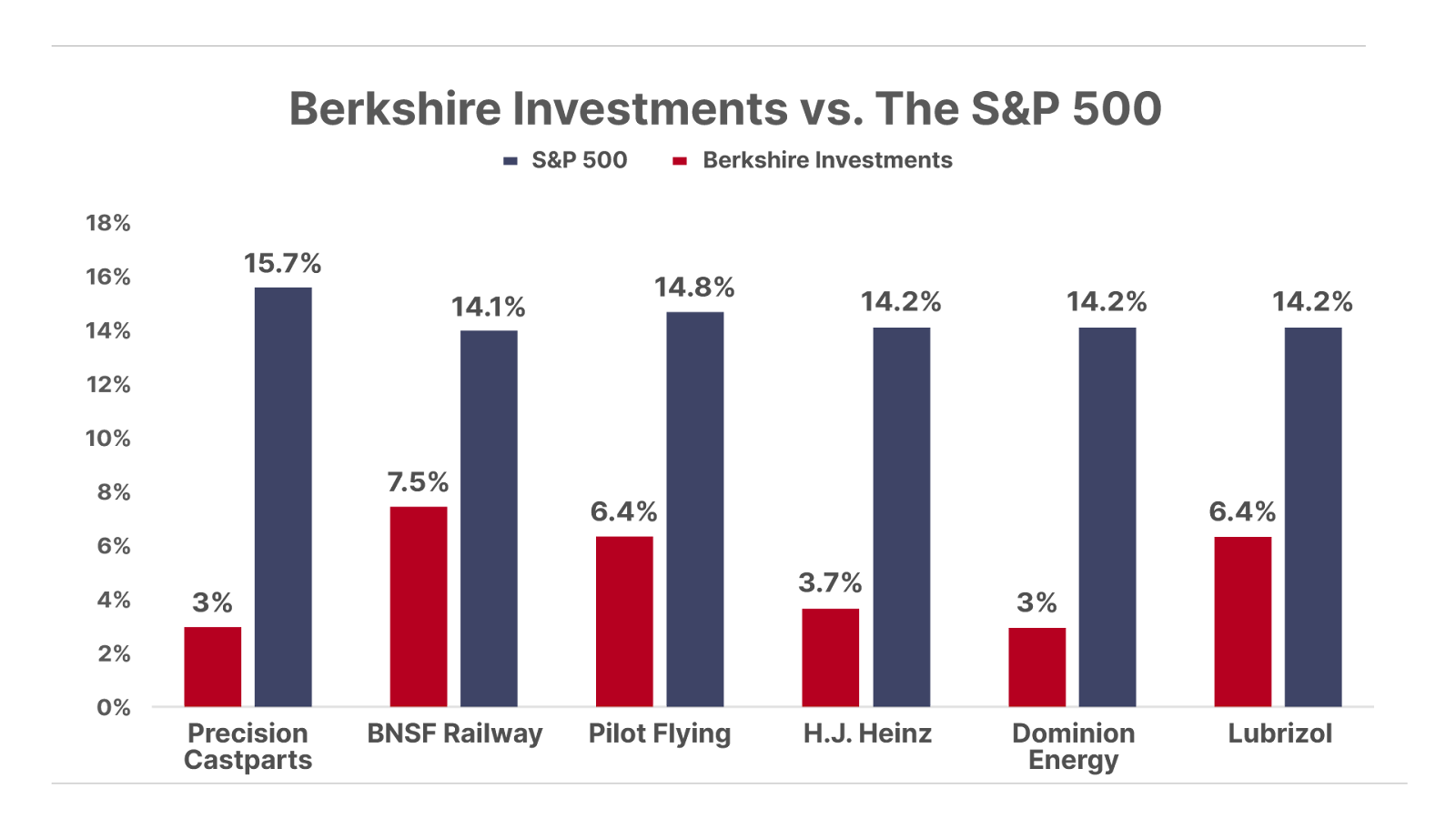

Since the financial crisis in 2008, Berkshire Hathaway has made six major acquisitions: Precision Castparts ($32.7 billion), BNSF Railway ($26.5 billion), Pilot Flying J ($14 billion), H.J. Heinz ($12.1 billion), Dominion Energy ($9.7 billion), and Lubrizol ($9.2 billion). Total initial invested capital: $104 billion, or roughly 12.5% of Berkshire’s entire equity.

To put the scale of these major investments into perspective, Buffett is justly famous for what was the greatest single investment of all time: plunging $41 billion into shares of Apple (AAPL) from 2016 to 2020.

But these whole-company investments were, combined, vastly larger. And, remember: these were all private transactions where Buffett had complete access to the company’s books. In these situations, he had a tremendous informational advantage.

And yet NONE of these acquisitions produced anything like an acceptable return. In each instance, Berkshire’s shareholders would have been vastly better off if Buffett had simply bought back his own stock or just bought into an S&P 500 Index fund.

Here’s a chart of the annualized returns of these investments (“ROIC”) versus the comparable S&P 500 return, annualized:

The lackluster performance of these subsidiaries isn’t the real problem. The real problem has been, faced with overwhelming evidence of poor management, Buffett has famously “sucked his thumb” – and been reluctant to replace his managers or sell these businesses.

In fact, in two notable cases (BNSF and what’s now called Berkshire Hathaway Energy) he’s aggressively invested more capital into these poorly performing businesses.

Since the acquisition, capital investments at BNSF alone have been over $50 billion. And Buffett has invested another $35 billion into more windmills at Berkshire Hathaway Energy (“BHE”).

As a result, $200 billion of Berkshire’s equity (or about 30%) resides in these three lackluster businesses: BNSF, BHE, and Precision Castparts. These make up most of Berkshire’s manufacturing, service, and retailing (“MSR”) business unit. None of these businesses are capable of producing even average returns on equity. They are an anchor tied to the Berkshire ship.

And here’s the really bad news.

Two of these six businesses (Precision Castparts and what is now Kraft Heinz) have already taken multibillion-dollar write-offs. They won’t be the only ones.

It is only a matter of time before Berkshire Energy takes a $20 billion+ write off.

How do we know? First, because BHE isn’t earning its cost of capital. Second, because it relies heavily on government tax credits and other government incentives that, under the Trump administration, are almost certain to be curtailed. And, third (and most importantly), because this business unit faces enormous liabilities related to western wildfires, damages that could be as much as $40 billion… there’s that number again.

Although Berkshire hasn’t written off this amount yet, Buffett clearly knows the unit is deeply impaired. In June 2022, Berkshire acquired BHE chairman Greg Abel’s 1% stake in BHE for $870 million, implying a market value of $87 billion. More recently (in September and October of last year) Berkshire acquired the remaining 2.12% of BHE that it didn’t already own from the family of Walter Scott, one of Buffett’s oldest business partners. The new valuation? $48 billion. The difference? More or less $40 billion.

That means, either Buffett is cheating the family of one of his best friends (not possible) or else the value of BHE has fallen in half.

Not many people will remember, but in 2018 the daughter of our Biotech Frontiers analyst Erez Kalir brought down the house at the Berkshire annual meeting by taking Buffett and Berkshire co-chair Charlie Munger to task for making a series of poor investments coming out of the Global Financial Crisis (See the video here).

We expect Erez and his daughter will be at Berkshire’s annual meeting in May… and we hope she’ll get another shot at asking Buffett some tough questions about these poor investments.

For now, we continue to believe Berkshire’s future performance will be weighed down by the prior two decades of subpar capital-allocation decisions. That’s why we’re not recommending shares of Berkshire Hathaway today. Instead, we’ve found the ultimate replacement stock.

We call it the Baby Berkshire, because its market cap is minuscule in comparison, at less than 2% of Berkshire Hathaway’s $1.1 trillion. But we believe that’s one of its greatest strengths. This business started with the original Berkshire plan of building a foundation of steady cash flows around a core insurance business and carefully reinvesting those earnings into high-quality businesses within the circle of competence of its managers. And it’s stayed true to that simple formula for the last eight decades.

Instead of building an empire of disparate and hard-to-manage businesses, the owners have increasingly simplified the operating structure. Today, it owns a handful of core subsidiaries that produce reliable cash flows even through periods of economic and financial turbulence. And with its disciplined capital-allocation strategy, when management finds nothing better to invest in, it simply buys more of its own shares. That’s how the company has eliminated 80% of its share count over the last 30 years.

The current management team plans to continue executing this plan for the foreseeable future. In this issue, we show why this business offers a clear path toward compounding shareholder capital at 15% per year over the next decade, without taking much risk along the way.

Turning A $125,000 Loan Into A Multi-Billion Dollar Conglomerate

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care Concierge, Lance James, at 888-610-8895.