The precious metal has been the world’s “hardest” money for 2,500 years. But that may not be the case much longer.

But Bitcoin Could Ultimately Replace It

The press called him “The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

After killing a man (some sources say two) in a dockside brawl in Georgia sometime in the 1860s, red-headed adventurer David O’Keefe sought sanctuary on the remote Pacific island of Yap. There, he settled down with a native woman (some sources say two).

And eventually he established himself, not exactly as a king, but as the head coconut merchant on the island.

Along the way, he did something that not even today’s Federal Reserve has been able to do (yet) to the U.S. dollar: He completely destroyed the Yapese form of currency.

Yap money wasn’t gold, silver, or paper bills. The islanders’ legal tender was massive, doughnut-shaped stone disks called fei – some as large as 10 feet across. Carved from a special, shiny limestone, they were quarried on an island 250 miles away and ferried to Yap via canoe. They were scarce, difficult to carve with primitive shell tools… and precious.

In between romancing the ladies and introducing cheap rum to the gents, O’Keefe looked at the hatchback-sized round stones and saw opportunity.

His big idea: Give the Yapese modern tools to carve and transport fei. Then use the fresh supply of stone money to pay other Yapese people to harvest coconuts (in those days, a sought-after source of lamp fuel in Europe).

For a few years… long enough for O’Keefe to make a fortune, anyway… the plan worked perfectly.

By 1882, 400 Yapese (a tenth of the island’s population) were hard at work carving fei with metal tools, transporting them on sturdy boats, and accepting them as payment for work on O’Keefe’s bustling coconut plantations. The coconuts themselves – 30 trade vessels’ worth per year – netted the “King of the Cannibal Islands” what amounted to more than $10 million in today’s money over the course of his trading career. (The wild tale was eventually fictionalized in a 1954 Burt Lancaster movie called His Majesty O’Keefe.)

But in the process – if you’re a student of economics, you may see where this is going – the stone coins of Yap became worthless.

The influx of new fei – now, too easy to mine, carve, and transport – inflated the Yapese economy but in time destroyed the value of the islanders’ savings. After O’Keefe fled the island in 1901 – driven out by political unrest and invasive, coconut-destroying “leaf lice” – the Yapese fell prey to first German, then Japanese colonizers, and ultimately were forced to adopt foreign currencies. The once-treasured fei were repurposed as ballast and anchors.

Today, the big, round stones are still scattered all over the island of Yap (now part of the Federated States of Micronesia)… cautionary monuments to the dangers of “easy money.”

What Is Money?

Throughout human history, various goods have served the role of money. In addition to the Yapese’s prized fei stones, these include basic items like seashells, salt, and glass… refined metals like gold, silver, and copper… and of course, countless iterations of government-printed paper.

Yet among them all, only gold has stood the test of time. It alone has maintained its monetary role for more than 2,500 years.

This is not happenstance. But to understand why gold has endured, let’s first review the primary roles of money.

The first – and most fundamental – role of money is to serve as a medium of exchange. A medium of exchange is an item that is acquired for the sole purpose of being traded (exchanged) for other goods, rather than consumed directly or used in the production of other goods or services.

Without a widely accepted medium of exchange, an economy must rely on barter or direct exchange, making efficient trade difficult. For any transaction to take place in a barter system, there must be a mutual need: what one party wants to trade must be precisely what another party seeks. For example, if an apple farmer wants to trade for bread, he must find a baker who wants to exchange bread for apples. This “coincidence of wants” becomes more difficult to arrange the more complex an economy grows.

A fei, a gold coin, or dollar bill became the medium to execute these exchanges.

The second role of money is to serve as a store of value – a means to preserve wealth and transfer purchasing power into the future. This function is critical for capital accumulation… without it, investment – and the specialized production of our modern economy that it enables – would be impossible.

Finally, the third role of money is to serve as a unit of account. Widespread acceptance of a particular good as both a medium of exchange and a store of value allows the prices of other goods to be expressed in its own uniform terms, in turn enabling the “invisible hand” of the market to work its magic. The farmer’s apple and the baker’s loaf can be expressed in a value not related to the other item.

Any number of goods could potentially serve as a medium of exchange. All that is truly required is that it has three traits.

It must be scalable – that is, able to be divided into smaller units or grouped into larger units, allowing its holder to use it in any quantity necessary. Think pennies to $100 bills. It must be portable – easily transported and transferable. That’s why we have wallets and purses. And it must be fungible – each unit is interchangeable with any other. “Give me two fives for a 10, please.”

“Hard” Versus “Easy” Money

To maintain purchasing power over time – to act both as a medium of exchange and as a store of value – a monetary good must be physically durable as well. It must be resistant to rot, corrosion, and general deterioration.

However, durability alone is not enough. As the natives of Yap Island (and countless other societies throughout history) learned the hard way, money can lose significant value even if it remains in good physical condition.

To serve as a dependable store of value, the supply of a monetary good must also remain relatively stable over time.

For this reason, many earlier forms of money shared some kind of natural restraint on their production. Salt was relatively rare and hard to obtain for much of history. Likewise, primitive monies like Native American wampum shells, African aggry beads, and fei stones required significant time and effort to create when they were originally adopted.

In fact, this relative difficulty is where the terms “hard money” and “easy money” originate… When a money’s supply is difficult to increase, it’s considered “hard,” and vice versa.

One of the best ways to assess a particular money’s hardness is through a metric called the stock-to-flow ratio.

This ratio compares the existing supply (or stock) of a monetary good – which includes all that has been produced in the past, less any amount that has been consumed or destroyed – to how much new supply (or flow) can be produced in a given period (typically a year).

The higher the stock-to-flow ratio, the harder the money and the more likely it is to maintain its value over time.

This dynamic implies that the hardest money – and the best store of value – would be one that not only has a relatively low flow, but also a relatively high stock. When viewed through this lens, gold’s advantage over other historical forms of money becomes clear.

Why Gold Continues to Win

Again, most monetary goods – including gold – were relatively difficult or energy-intensive to obtain at the time of their adoption. Their flow was relatively low.

However, gold’s physical durability is unique. The metal is so chemically stable that it is virtually impossible to destroy. And unlike many other commodities, only a relatively small proportion (about 3%) of gold production is consumed in industrial uses.

This combination of traits means most of the gold that has ever been mined is still owned today, giving it an extremely high stock compared to other monetary goods.

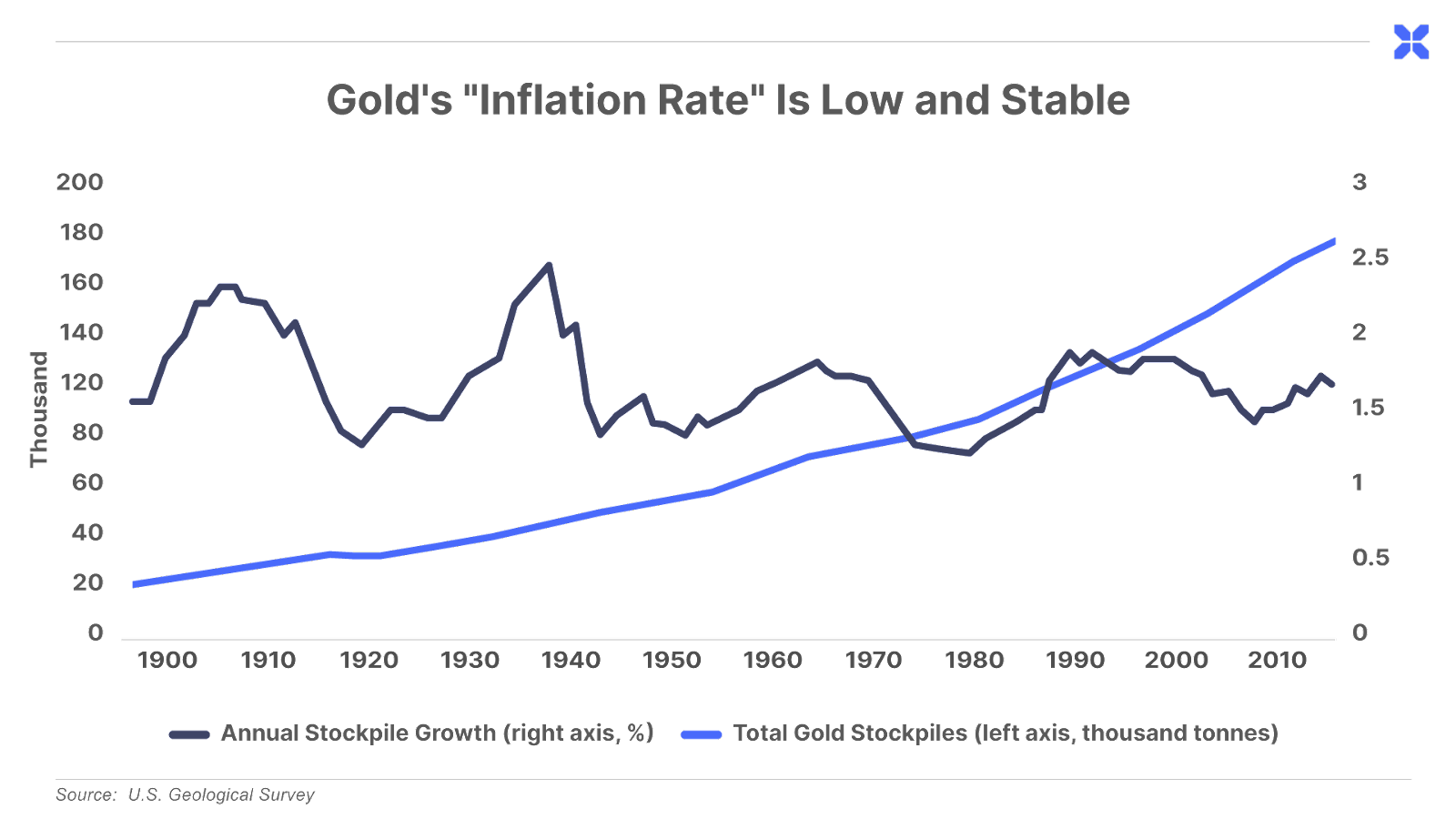

This vast and ever-growing existing stock means producers can only “inflate” the gold supply by an average of around 1.5% a year, despite ongoing technological improvements that make mining ever more efficient. And this figure has been remarkably stable over time, regardless of fluctuations in the price of gold.

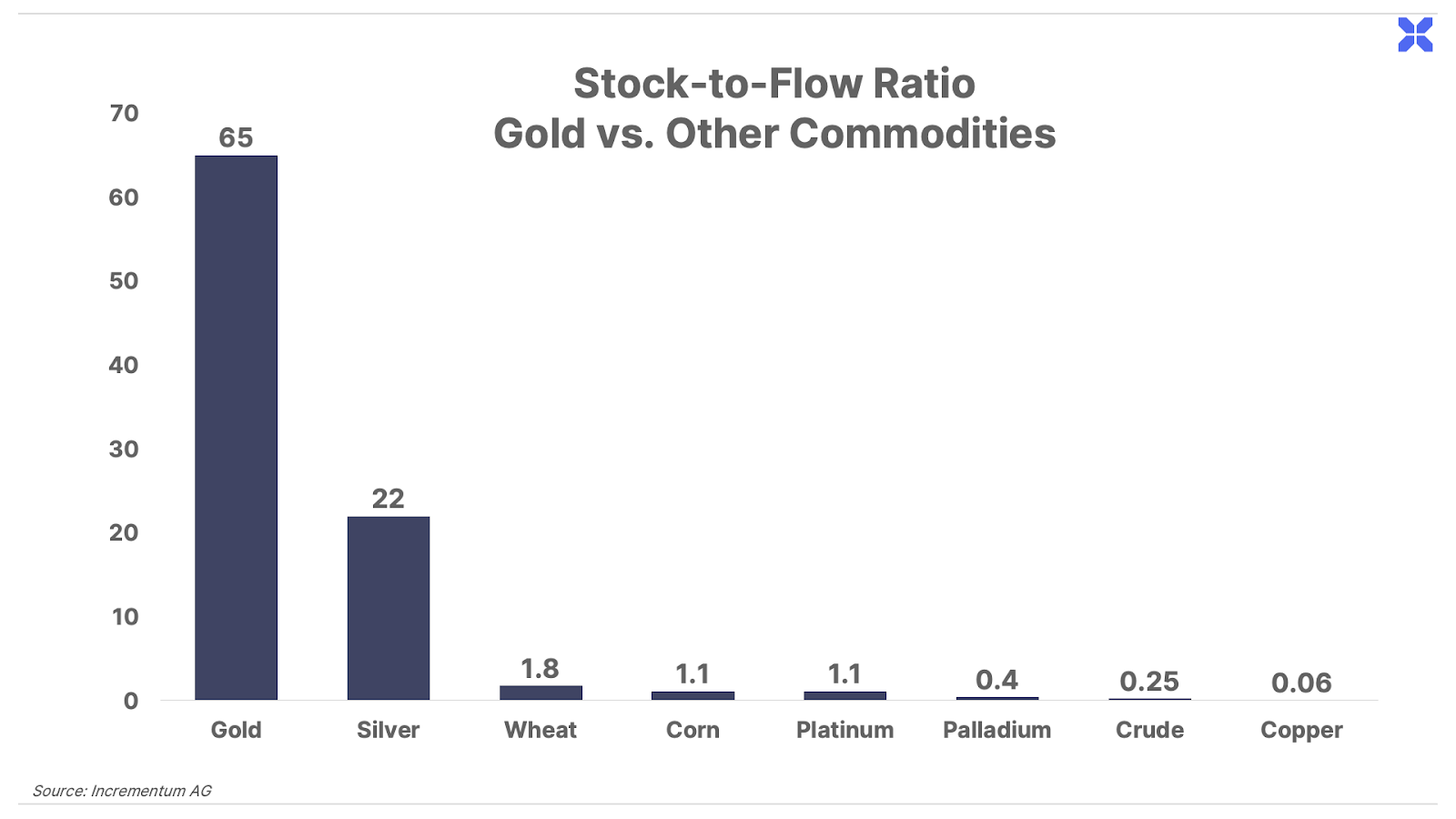

The total amount of existing gold is estimated to be around 200,000 metric tonnes today. At the current annual production rate of around 3,100 metric tonnes, this represents a little more than 65 years’ worth of supply – giving gold a stock-to-flow ratio of around 65.

The stock-to-flow ratio for fiat currencies is theoretically zero, as there is technically no limit to how much new currency can be created. In practice, the U.S. money supply has increased by about 10% annually since the dollar was officially severed from gold in 1971. That equates to a stock-to-flow ratio of roughly 10, though this number is likely to plummet in the years ahead as the government has no choice but to paper over its soaring debts.

By comparison, the stock-to-flow ratio for most commodities other than gold and silver is generally around one, indicating that new production roughly equals or exceeds existing global stocks that are constantly being consumed.

When savers choose to store their wealth in one of these “easy” forms of money, a predictable cycle emerges.

First, the increased demand for the commodity causes the value of the money to rise… Rising prices then incentivize producers to invest in increased production… This increased production then greatly expands the supply of the commodity… And finally, soaring supply causes the value of the money to crash – effectively transferring the wealth of those savers to the producers of the commodity they bought.

This was exactly what happened to early savers who continued to hold their wealth in primitive monies like salt, seashells, or fei after technology caused their stock-to-flow ratios to plummet. And a similar dynamic has impoverished countless others who saved in modern fiat currencies in the centuries since.

But gold’s unique properties make it immune to this cycle.

Because so much gold already exists, even if new gold production were to double overnight, it would result in only a 3% annual increase in total supply. Meanwhile, the simultaneous growth in gold’s existing stock would make each additional annual increase less significant, even if that rate of production is maintained.

In other words, unlike most other monetary goods, it is practically impossible to create enough new supply to suppress the price of gold significantly.

Among commodities, only silver comes close to rivaling gold. Its stock-to-flow ratio is around 22 – indicating one-third the hardness of gold.

Silver is “easier” money than gold for two important reasons. First, silver is significantly less rare and easier to refine – giving it a higher flow than gold. Second, silver is less chemically stable than gold (it can corrode) and significant quantities are consumed in industry. The metal plays a critical role in a huge number of products including batteries, nuclear reactors, semiconductors, touch screens, and water purification – meaning its existing stock is much lower than the existing stock of gold.

Despite these drawbacks, silver was used as money alongside gold for thousands of years – its lower value per unit of weight made it more convenient for smaller transactions. However, the widespread adoption of the gold standard in the late 19th century enabled gold-backed paper transactions that eliminated this need, ultimately causing silver to lose its monetary role.

Why “Digital Gold” Is the Future

No current discussion of hard money would be complete without mentioning Bitcoin.

We’ve detailed many of the reasons for owning Bitcoin previously. This decentralized, digital currency allows seamless monetary transfers to anyone around the globe with the click of a button. And its peer-to-peer transfer arrangement means it exists outside the scope of governments and central banks.

However, Bitcoin is also the first money in history whose stock-to-flow ratio rivals – and could eventually, exceed – that of gold… suggesting Bitcoin could ultimately become an even better long-term store of value than the time-tested precious metal. Bitcoin’s big advantage is that both its total stock and flow are mathematically predetermined via software.

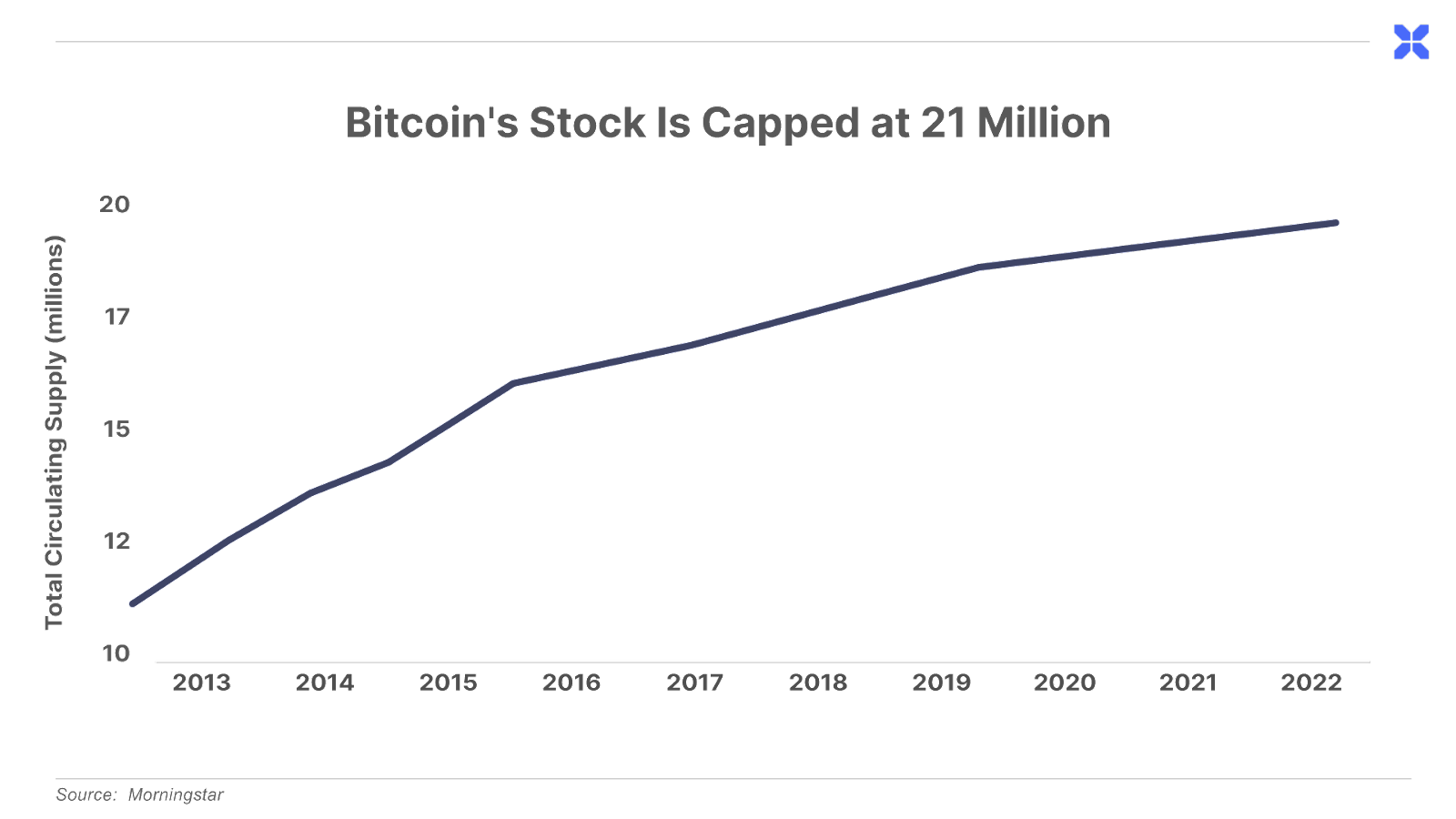

As decided by its creator, there will only ever be 21 million Bitcoin – of which a little over 19 million have already been mined.

Meanwhile, we know Bitcoin miners are currently awarded 6.25 new Bitcoin per “block.” With a new block being mined roughly every 10 minutes, this equates to an annual “flow” of around 328,000 new Bitcoin.

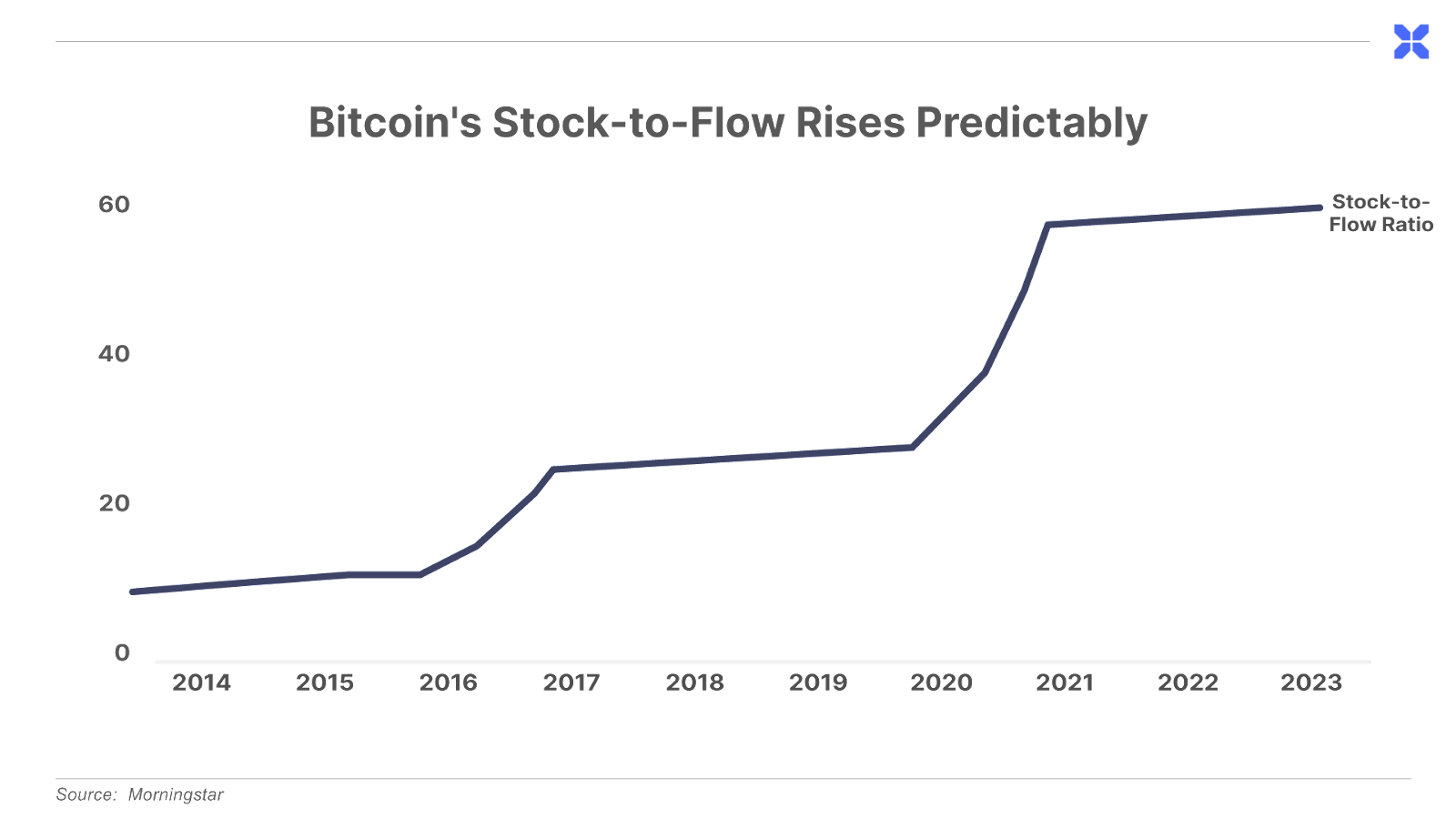

Dividing the current stock of around 19 million by this figure gives us a stock-to-flow ratio of a little less than 60. This is closer to gold’s ratio of 65 than any other commodity.

However, this won’t be the case forever.

Bitcoin undergoes a halving after every 210,000 blocks are mined (roughly every four years). Each time this occurs, the amount of new Bitcoin miners receive per block is cut in half.

The next halving is expected to occur in early 2024. When it does, the block reward will drop from 6.25 Bitcoin to just 3.125. As Bitcoin’s flow drops by 50%, its stock-to-flow ratio should double to over 100.

This process will continue roughly every four years until all 21 million Bitcoin are mined and its stock-to-flow ratio effectively reaches infinity.

Of course, Bitcoin has only been around for about 15 years. It hasn’t yet weathered even a recession, let alone centuries of crises like gold. So, we certainly don’t recommend holding all your savings in Bitcoin.

But this mathematical certainty tells us that if Bitcoin does survive, it is likely to become the hardest money in history… and could ultimately become a global reserve currency, supplanting the U.S. dollar and potentially even gold.

For now we recommend all investors hold at least a small portion of their wealth in both gold and Bitcoin. Paid-up Big Secret subscribers can review our favorite ways to own gold here, and learn more about the benefits of owning Bitcoin here.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, you can get instant access to these special reports by signing up for the Big Secret on Wall Street today.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team, you can get acquainted with us here. You can follow me (Porter) here: @porterstansb.