America’s banking system teeters on the edge of insolvency. The stage is set for more bailouts, more inflation, and the End of America. Here’s how to prepare – and what to do with your money.

The Next Financial Crisis Starts October 17, 2023

How the Government’s Out-of-Control COVID Spending Set the Stage for the Next Crash

Trimming Our Portfolio to Survive 5%+ Yields

|

Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email your personal concierge, Lance, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected]. |

The reckoning begins on Tuesday.

For decades, America has lived well beyond its means. The ongoing 50-year deluge of money, credit, and soaring government spending began with Nixon’s (a Republican) repudiation of the gold standard on August 9, 1971.

America’s experiment with paper money reached its zenith – $7.1 trillion in unfunded government spending – in the insane over-reaction to the flu of 2020.

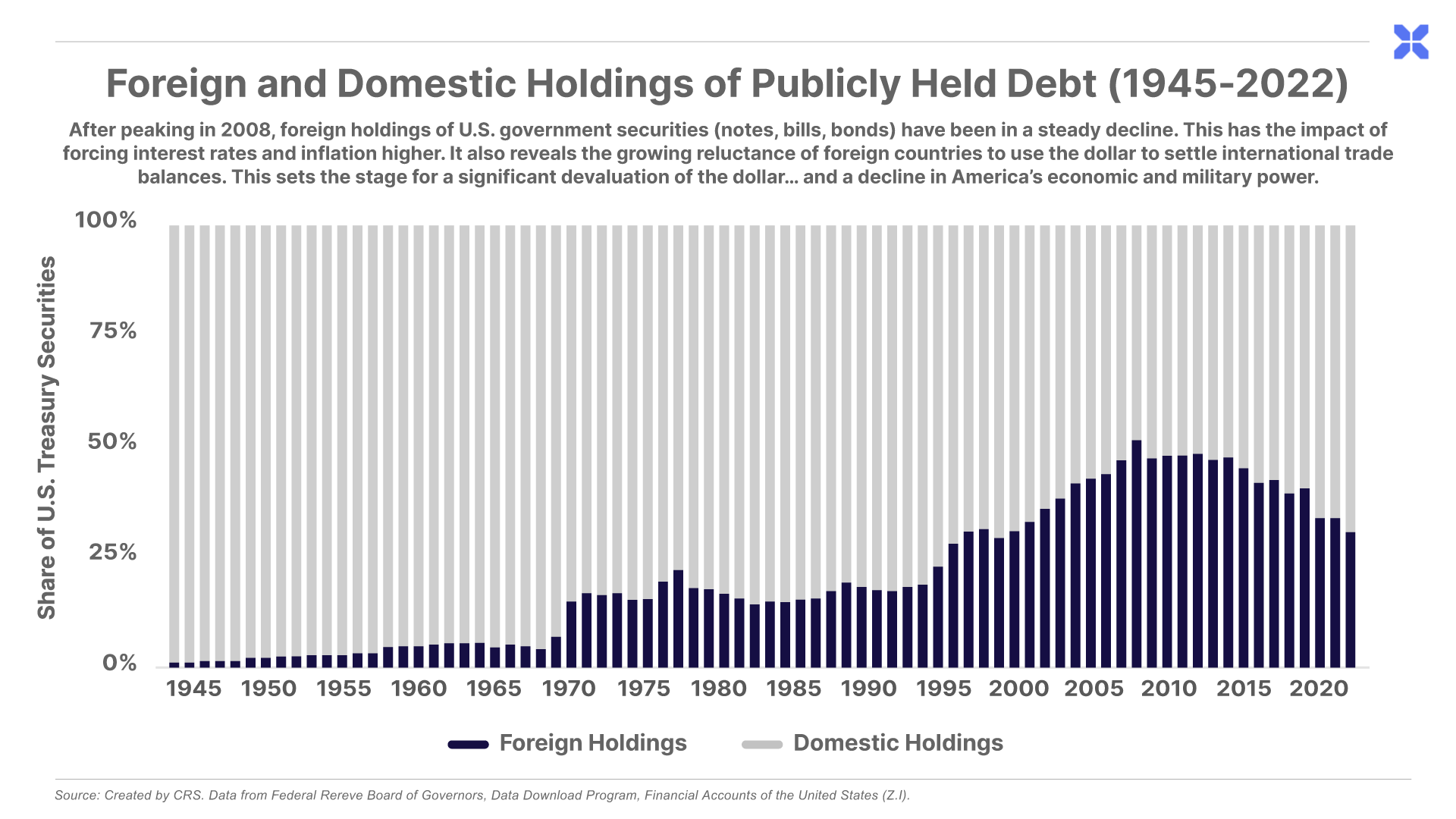

Looking back, historians will point to 2008, and the Global Financial Crisis, as the beginning of the end. That’s when our foreign creditors began to abandon our currency and our bond market.

Soon after, I (Porter Stansberry) first documented America’s looming disaster in the film “The End of America.”

The End of America (2010) was an economic and social prophecy.

It predicted that America, which was financing its government spending by debasing its currency, would enter into a debt spiral. And the consequences wouldn’t merely be financial. When countries begin to finance their government this way, what becomes debased isn’t merely the currency – but the entire society.

Absent financial constraints and protections for property rights, democracies rapidly devolve into competing parasitic factions, each attempting to live at the expense of the “other.”

The result is, inevitably, a continuing increase in government spending and government debts; a decline in the value of the private economy; and a concurrent decline in the standard of living.

This spiral also leads to a marked increase in social problems (gambling, prostitution, corruption, theft); soaring rates of both public (war) and private (murder) violence; a proliferation of rabidly competitive social, racial, and economic groups (strikes, racial tensions, demands for “social justice”); and a substantial rise in health problems associated with desperation, such as suicide, alcoholism and drug addiction.

Why? Why does debauching the money lead to debauchment of the society?

Money is not merely a means to facilitate exchange. It is not merely a store of value. And it is not merely a measure of accounts.

Money is, most importantly, the foundation of a market economy because of price mechanisms. IPrices discipline the market. Prices incentivize production. And prices – invisibly without additional costs – drive an economy towards greater efficiency.

The Invisible Hand

One of the greatest ironies of the modern world is how few people who enjoy the cornucopia of capitalism and free markets understand even the most basic elements of what creates wealth.

In 1776, economist Adam Smith – the founder of the entire discipline of economics, and of capitalism too – published his masterwork: An Inquiry into the Nature of Causes of the Wealth of Nations. In that book, Smith explained the essence of the price mechanism by describing how the incentives of the entrepreneur to enrich himself – in fact enrich the entire society.

He called this powerful, positive force of self-interest “the invisible hand”:

“By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an Invisible Hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.”

Prices guide the “invisible hand” by informing widely dispersed actors in a free market economy – with stunning efficiency. It’s how farmers know what to plant. How industrialists know what to produce. How capital markets know what to finance. Sound money (and relatively stable prices) create the incentives for risk taking and for saving capital.

Absent this mechanism for communication and for rewarding production, an economy quickly falls apart. Instead of creating abundance and opportunity, society is soon rendered into competing tribes, each organizing only for their benefit. The result is poverty, anomie, violence, and desperation. And these changes happen fast – within only a decade or so.

This week’s Big Secret On Wall Street is, ostensibly, about $1 trillion in losses that are being hidden (in plain sight) in our banking system. Most urgent are the massive losses at Bank of America. We believe these losses total at least $200 billion.

These losses, and the inability of Bank of America to pay a competitive interest rate for deposits, will soon trigger a run on the second-largest bank in America. The deposits will flee in a matter of hours. In fact, there isn’t any logical explanation for why such a run hasn’t already occurred. (Our advice: don’t be last in line.)

But, before you condemn our warnings as alarmist, know that everything that’s happening right now in America has happened before.

Maybe history only rhymes. But finance repeats.

How Britain Went Bankrupt: A Road Map to The End of America

Warren Buffett likes to dismiss gold. He complains gold has no utility. He complains (and we agree) it is a poor hedge against inflation.

Buffett says:

“Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.”

Buffett is like a Catholic priest offering marital counseling. He can describe the social contract – exactly what’s expected from each party – but he has no idea what he’s talking about. Or, as my long-time business partner, Bill Bonner, more eloquently says: it’s like a squirrel watching a bank robbery. Saw the whole thing. Never understood, in the slightest, what it meant.

To use Buffett’s analogy, if the people from Mars knew how governments manipulate (and steal) with paper money, they wouldn’t be scratching their heads. They’d insist any trade between Mars and Earth be settled in gold. And they should.

The purpose of gold – its utility – is to ensure that long-term economic relationships can be established and maintained efficiently, without either side having to resort to force. The value of gold is determined by the market, not by a central bank. It can’t be printed. Gold’s increasing supply is almost entirely determined by increases to industrial productivity – gains that are real, are hard won, and that require the willing cooperation of thousands of people.

That’s why gold has an unmatched 5,000 year history as a stable currency and store of value. From ancient Greece and Rome all the way up to modern day central banks, nothing else has maintained its value across countless cultures, geographies and economic regimes through time. It has been – for thousands of years – the ultimate free market currency.

Let’s contrast gold’s record with what happened to the world’s last great empire: the British.

Until the 1950s, the sun did not set on the British Empire. Its currency was, almost without exception, the international standard.

But… within 25 years of World War II… Britain’s own citizens were living in poverty and depending on external financing to pay for essential government services. Meanwhile, two of its most squalid territories, cities that were completely overrun by the Japanese, Hong Kong and Singapore, soon surpassed Great Britain in per capita wealth.

Why? Because they abandoned the British pound and based their free market economies on the U.S. dollar. They became two of the greatest cities in the world.

This economic history is worth studying. And, if we may be so bold, please share this analysis with anyone you think will give it some thought. It isn’t too late to save America, but the darkness gathers.

The story of how Great Britain went from being the world’s most dominant empire to becoming a beggar nation begins with the fateful decision, in 1914, to abandon sound money in favor of pursuing a global war without any defined strategic purpose.

In 1914, one day after declaring war on Germany, Britain suspended the public’s ability to exchange its currency (pounds) into gold.

Its monetary base rapidly doubled, generating a rising amount of inflation. This made financing its global war progressively more expensive. As the government raised funds in the world’s largest capital market (The City, in London), it had to offer higher and higher interest rates. By 1917, it had to offer a coupon of 5%. And because all of these war bonds offered holders the ability to exchange into future issues if the coupon offered was higher, virtually all of Britain’s outstanding war debt was converted into this, the Third Great War Loan.

Total capital raised and exchanged was 2 billion pounds. In some ways that’s equivalent to $348 billion today, but because these debts came on top of the pre-war government budget of only 200 million pounds, it’s very difficult to even imagine how enormous these debts were at the time.

This loan had one very important provision: no capital gains.

Britain believed it would return to the gold standard after the war. A return to the gold standard would, most likely, result in much lower prevailing interest rates. So, these bonds could be redeemed, at par, any time after 1929. That prevented these bonds from appreciating much once the war ended, and inflation declined.

By 1919, Britain’s national debt totaled 7.4 billion pounds, or 137% of GDP. (Hint: remember this figure.) Paying only the interest on these obligations required 30% of all tax receipts.

These debts, and the growing power of the government, warped the British economy and society.

More and more industries, and more and more capital, were directed by political forces, rather than market forces. Most notably, there was a huge increase in the amount of government transfer payments, which increased by seven-fold from the end of the war through the 1920s. To pay these bills, taxes soared.

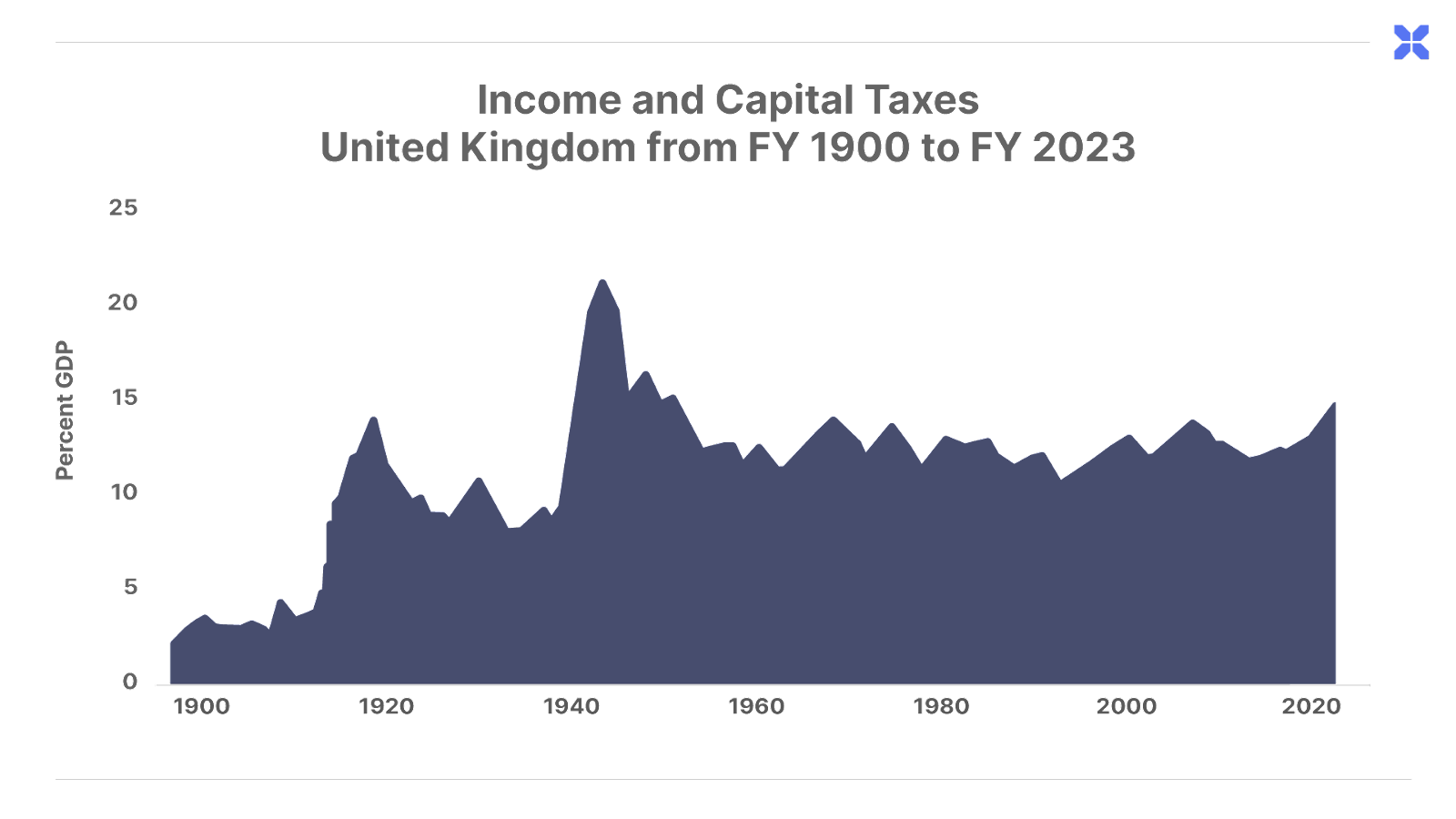

Income taxes rose from 5.8% to 30%. Prior to the war, income taxes were only levied on the rich – much like in America. But during the war, the tax was extended to millions of Britons. Revenues raised from income and property taxes (direct taxes) grew from around 50 million pounds a year in 1913, to 400 million pounds a year by 1919 (+700%).

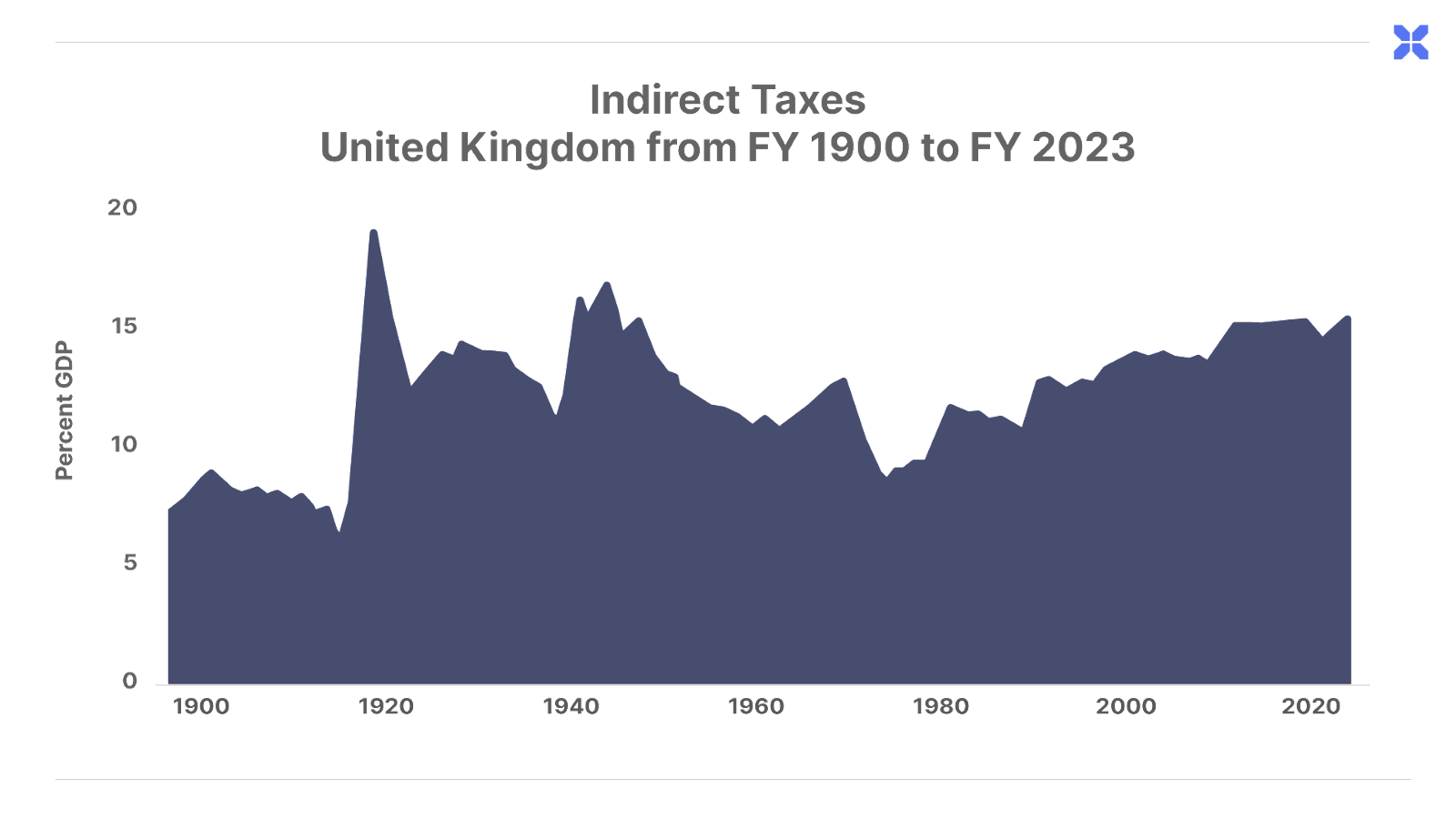

Even more damaging to the economy were “excess profits” corporate taxes, which began in 1917. These taxes seized 80% of whatever was deemed “excessive.” These, and other “indirect” taxes, such as levies on imports and luxury goods, came to equal 30% of the government’s budget.

As a result, taxes, which had been below 10% of GDP for decades, rose to account for more than 20% of GDP. That enabled vastly more government spending: The government’s annual budget grew from 200 million pounds a year before the war to almost 1 billion pounds after the war. Socialism had taken root.

What happened next?

With 80% of “excessive” corporate profits being taxed and with so much of the economy being directed by political factors, Britain’s post-World War I economy never regained its global competitiveness. Unemployment soared in Britain’s export trades: shipbuilding, engineering, steel, and wool textiles. Before the war, exports made up 25% of GDP… but by 1920… they’d declined to only 18%.

In the eight years between 1923 and 1931, real GDP growth was negative 18%.

The British economy was in a permanent decline because of the socialist policies they’d adopted after World War I. Higher taxes and more government spending wasn’t creating prosperity – no matter what the politicians promised.

By 1931, with a global recession underway, 2.5 million people were unemployed in Britain – more than 20% of the workforce. The government’s unemployment fund was borrowing more than 100 million pounds per month, or 5% of GDP, to pay unemployment benefits. This caused government spending to double. As the government’s deficits exploded, there was no orthodox way to continue to make interest payments. So, in September 1931 Britain left the gold standard and began to monetize their debts.

So… with total debt to GDP at around 130%… and transfer payments exploding, causing a doubling of government deficits… Britain began its final collapse.

Sound familiar?

According to the Federal Reserve, the U.S. government debt to GDP ratio peaked in the 2Q of 2020 at 132%.

And since then, annual government deficits have exploded – reaching over $2 trillion this year – because of unconstrained spending on transfer payments.

When You Abandon Sound Money, You Go Broke

Leaving the gold standard meant the Bank of England could print whatever money was needed to finance the government’s debts. And they did.

The global depression and financial uncertainty led to a dearth of new bond issues. But the British government wasn’t taking any chances. To make sure the value of government bonds soared, they outlawed any new bond issues and began monetizing the debt. The combination of massive amounts of new money, a collapsing economy, and no new bond issues resulted in bond prices soaring (and bond yields declining).

After manipulating bond yields lower – to around 3% – the government saw the opportunity to refinance its huge war debts. In July 1932, at the very bottom of the Great Depression, Britain exchanged 92% of its Third Great War Loan into the new 3.5% War Loan. Famously, the only British bank that refused to convert, The Midlands Bank, was bought out at par, so the British could claim that every major domestic holder of the bonds willingly converted.

Why would investors swap into a lower coupon bond?

Because the new issue didn’t include a provision to be repurchased at par. Investors in these new bonds, ironically, believed they would see capital gains because they believed that interest rates would move even lower than 3%. Why did they believe that? Because the Bank of England was monetizing so much short-term debt that one-year notes were yielding less than 1%. Banks thus had a choice: own short-duration government bonds that were paying almost nothing, or own perpetual bonds (which would only be paid off at the government’s option) for around 3.5%.

British banks’ holdings of government bonds soared. They grew by 50% in 1932 with the big war bond conversion. And, by 1938, British banks held 75% of their deposits in British government bonds.

So… to summarize… Britain moved off the gold standard in 1914 to finance a European war that even today no one understands. As the government became the primary actor in its economy, taxes soared, resulting in a moribund economy that eventually would have defaulted on its war debts. But, rather than default, Britain abandoned sound money (the gold standard) and began to monetize its debts, while, at the same time, encouraging its banks to buy very long duration bonds.

You’ll never guess what happened next.

Britain, once again, enmeshed itself in a ruinous European war by promising to protect the sovereignty of Poland in 1939. That didn’t work out so well: Poland was occupied for the next 50 years or so by the Russians. But Britain ended up with a national debt that was completely unfinanceable – about 250% of GDP – and was never able to return to the gold standard.

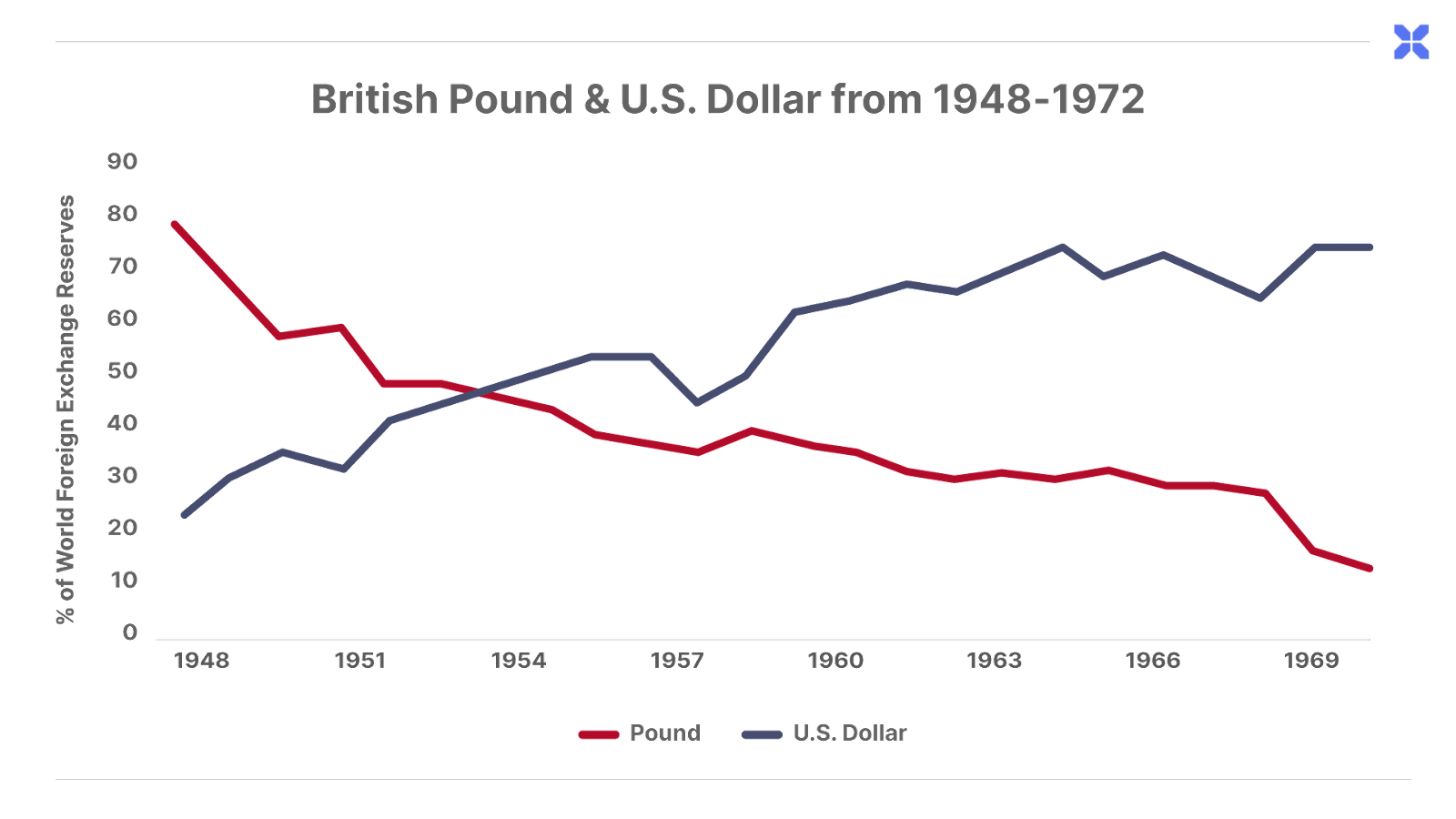

Over the next 25 years – from 1947 until 1972 – it employed a variety of currency controls like the Exchange Control Act of 1947. These controls were designed to try to force Britain’s trading partners to hold its bonds and currency. Meanwhile, crisis after crisis – mostly in foreign policy – caused repeated rounds of currency devaluation so that, by the 1960s, Britain was completely broke. Its entire global trade dominance had been destroyed, along with its economy, its military might, and its currency.

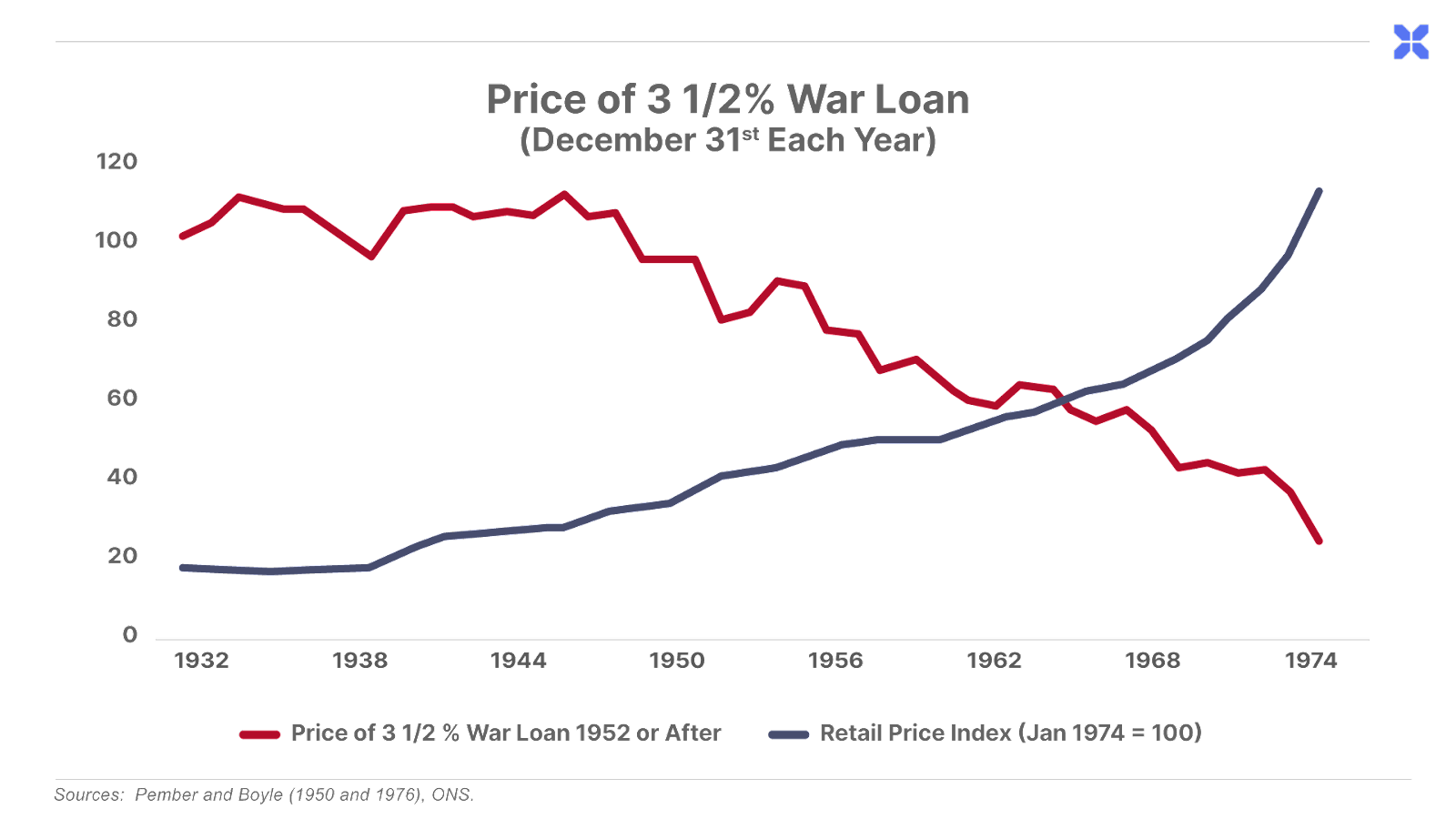

The chart above shows what happened to the British pound during the period. Even as late as 1948, the British currency continued to be the world’s reserve currency, which allowed its central bank the ability to borrow enormously. But… as repeated devaluations harmed its trading partners… more and more central banks turned to the U.S. dollar to settle trade.

And… what happened to the British banks that invested in long-duration bonds?

As the graph below shows, the price of those bonds plummeted over time, eventually falling 99% from their peak in U.S. dollar terms, decimating the banks’ balance sheets. And, as the bonds collapsed, so did the purchasing power of the British pound.

What’s very important to know is… virtually all of these same things have been happening to America since 1971. And, thanks to digital banking and the creation of Bitcoin, the flight out of the dollar as a global currency and collapse of our bond markets isn’t going to take 20 years. It’s happening right now. We suspect it will all be over in the next 12 to 36 months.

“Unrealized Losses” Are About to Get Very Real

During COVID the government printed enormous amounts of money and manipulated bond rates to their lowest point ever. Our banks faced the Hobbesian choice: earn nothing on safe short-term U.S. Treasury notes or earn 1.5% or so on long term U.S. Treasury bonds and longer duration mortgages.

Bank of America made the largest investment in its history. It bought $760 billion of long-term U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgages, with most of the purchases occurring in mid-2020 at the absolute peak in long-term bond prices.

Similar bonds have now declined 50% from their peak. We don’t know – yet – exactly what Bank of America’s losses have been, but we do know the bank reported unrealized losses of $109 billion as of Q2 2023. These losses are not caused by defaults, but merely because inflation has radically reduced the real value of these bonds – enormously. We suspect that, this coming Tuesday, when Bank of America reports 3Q earnings the losses on these long term bonds will have exceeded its $175 billion in tangible equity capital, meaning any sustained run on its deposits would render it insolvent.

Why isn’t anyone else concerned? If you Google and research these issues, you’ll find recent articles by The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg that downplay these huge losses. You see, because the bank designates these investments “long-term holdings,” the losses don’t count against its required capital base.

Among the reasons the mouthpieces of the government say we shouldn’t worry? Well, because Bank of America isn’t alone in this dilemma.

Through the end of Q2 2023, U.S. banks were sitting on $550 billion in unrealized losses from their holdings of long-duration Treasuries and MBSs. That’s nearly 25% of the total equity capital in the U.S. banking system.

That doesn’t reassure us.

Instead, we think that proves our point. Think of it this way. Much like Britain in World War I, our government wasted $7 trillion on a completely unnecessary war (against the flu). There was no economic return on these investments. But… where will these losses materialize? Seems pretty clear that the government has done a great job of foisting these bad debts onto banks – most notably Bank of America.

And here’s the real issue.

In today’s world, 100% of bank deposits are only a few taps on a cell phone from heading out the door. Bank of America, due to its massive purchases of low-yielding long-term bonds, currently has an average portfolio yield of only 2.44%. There’s no way that Bank of America can pay anything like short-term Treasury yields in excess of 5%.

Thus… it is only a matter of time before depositors wake up. They’re not being paid anything like a fair rate of return. And, Bank of America is, mostly likely, already insolvent. Thus, the only thing that’s keeping Bank of America alive is… no one has noticed yet.

That doesn’t seem like a solid foundation to us.

When a run happens, it won’t take days or weeks. It will take hours.

That’s exactly what already happened to SVB Financial, where the unrealized losses don’t compare to those Wells Fargo and Bank of America are sitting on.

This situation isn’t merely speculation.

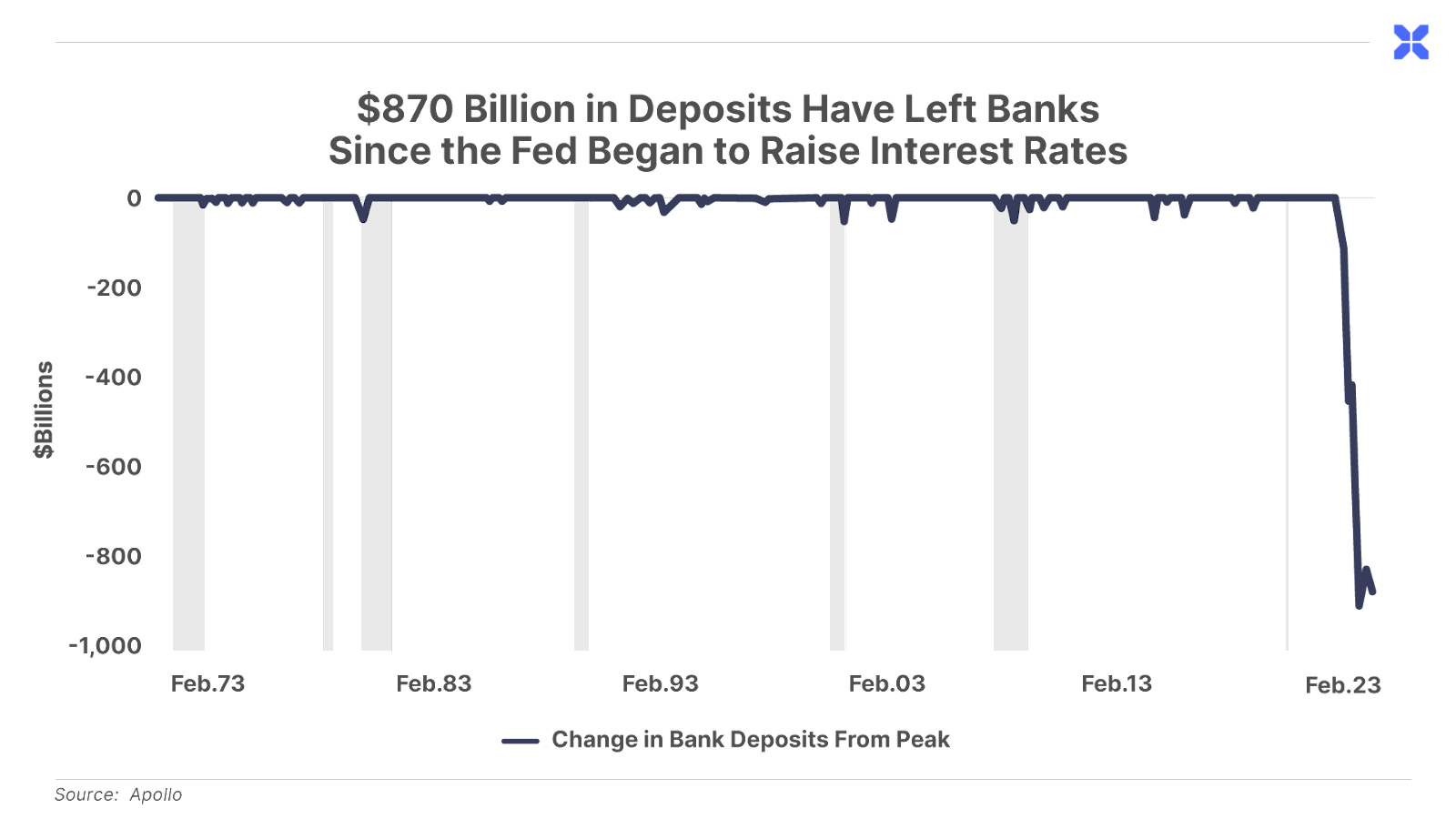

In the 18 months since the Fed started raising rates in March 2022, depositors have yanked nearly $1 trillion from U.S. banks. Never before in history have we seen deposit flight on this scale.

When will you pull your deposits? If that chart doesn’t tell you what to do, we probably can’t help.

My advice: don’t wait. To quote John Tuld from the famous Wall Street movie Margin Call, “if you’re first out the door, it’s not panicking.”

Oh… one more thing…

The banking sector’s losses on investment securities is only part of the problem.

These institutions are also sitting on an estimated $120 billion in losses from commercial real estate loans. Richard Barkham, chief economist at CBRE – the world’s largest commercial real estate investment firm – estimates these losses would wipe out 100% of the tier-one capital buffer at over 300 U.S. banks.

That’s on top of any expected losses that would normally occur during a credit-cycle downturn. We expect record defaults in the unprecedented $5 trillion of consumer credit spanning auto loans, credit cards, student debt and personal loans, not to mention nearly $3 trillion in commercial and industrial loans.

Another Bailout in a Long Line of Bailouts

While it might seem imprudent to keep these enormous potential losses on the books, the banks have historical precedence on their side. In every financial crisis since its inception in 1913, the Fed has bailed out America’s lending institutions.

With each crisis since then, the scope of the Fed’s intervention has expanded into new territory. As a result of the 2008 mortgage meltdown, the central bank changed its mission from only buying Treasuries to purchasing MBSs as well. Its new quantitative easing (“QE”) programs – providing virtually endless amounts of cheap money – created $4 trillion in new currency over the subsequent decade to indirectly monetize ballooning government deficits.

During the 2020 COVID meltdown, the Fed expanded into buying corporate bonds for the first time. It also launched a record QE program to subsidize $10 trillion in government spending, creating $5 trillion in new currency in just over two years.

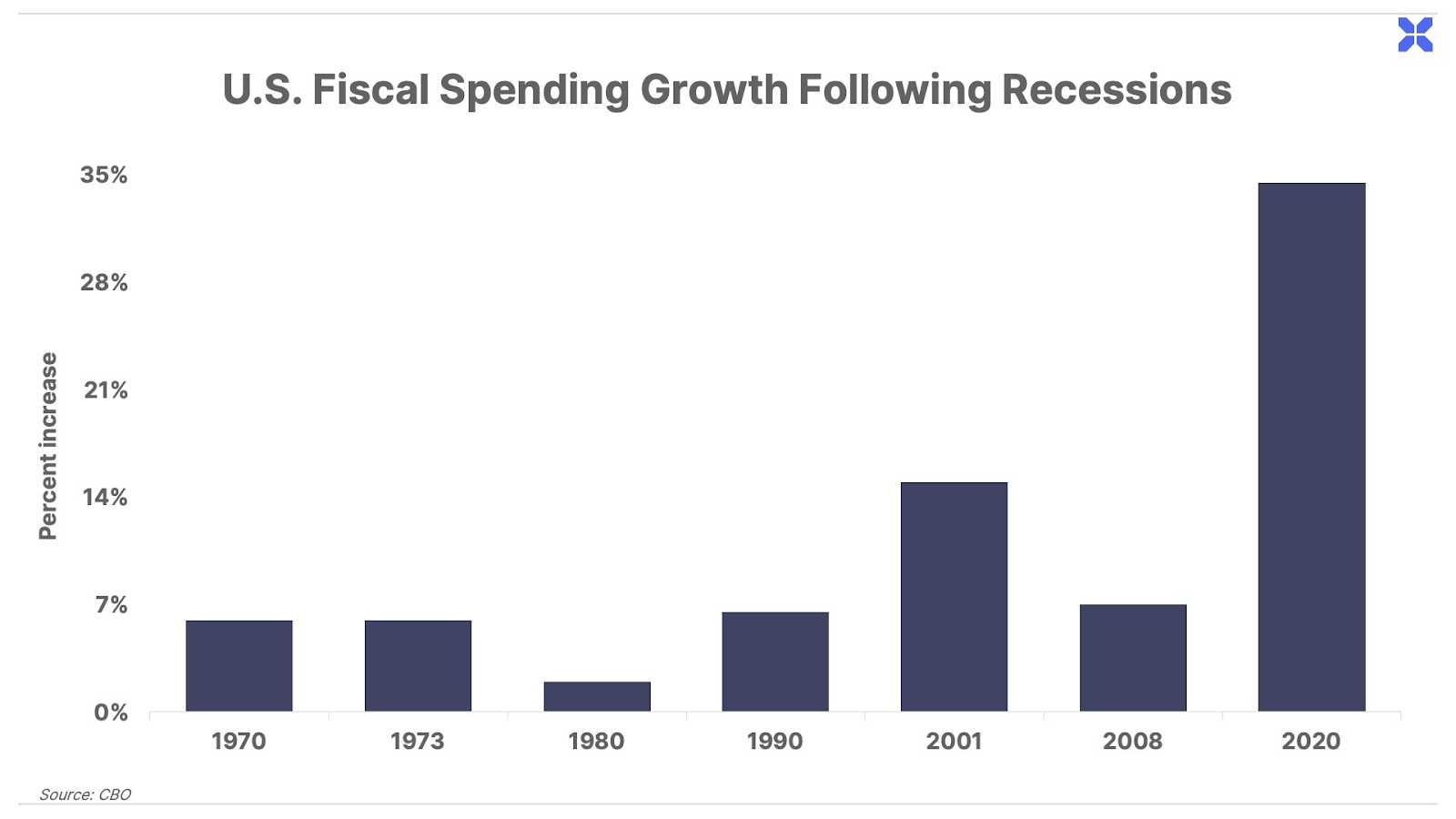

The following chart measures the amount of non-defense-related government spending increases from when a recession began. As we can see, from the start of the short downturn brought on by the pandemic, spending increased by almost 35%. That’s 5x the 7% increase during the 2008-09 Financial Crisis. And it’s more than double the 15% bump in 2001.

In the next crisis, the Fed’s intervention will once again venture into uncharted territory. Bailing out the banking sector from trillions in underwater Treasuries, mortgage securities, and commercial real estate loans will not solve the underlying problems, but simply paper over them.

The real problem, of course, is that these bailouts are financed with currency conjured from thin air – there is nothing intrinsically backing this money. In the past, foreign governments subsidized America’s endless bailouts by providing steady demand for U.S. currency and Treasury bonds. But now, the world is waking up to the downside of becoming the lender of last resort to an insolvent borrower.

Today, the biggest credit risk of all lies with the U.S. federal government, and the currency it stands behind – the U.S. dollar.

The Final Bailout and the End of America

When policymakers inevitably bail out America’s banking system in the coming crisis, it will push America’s debt burden past the point of no return. This will lead to a bailout of the Federal Government, as the central bank is forced to become the buyer of last resort of U.S. government debt.

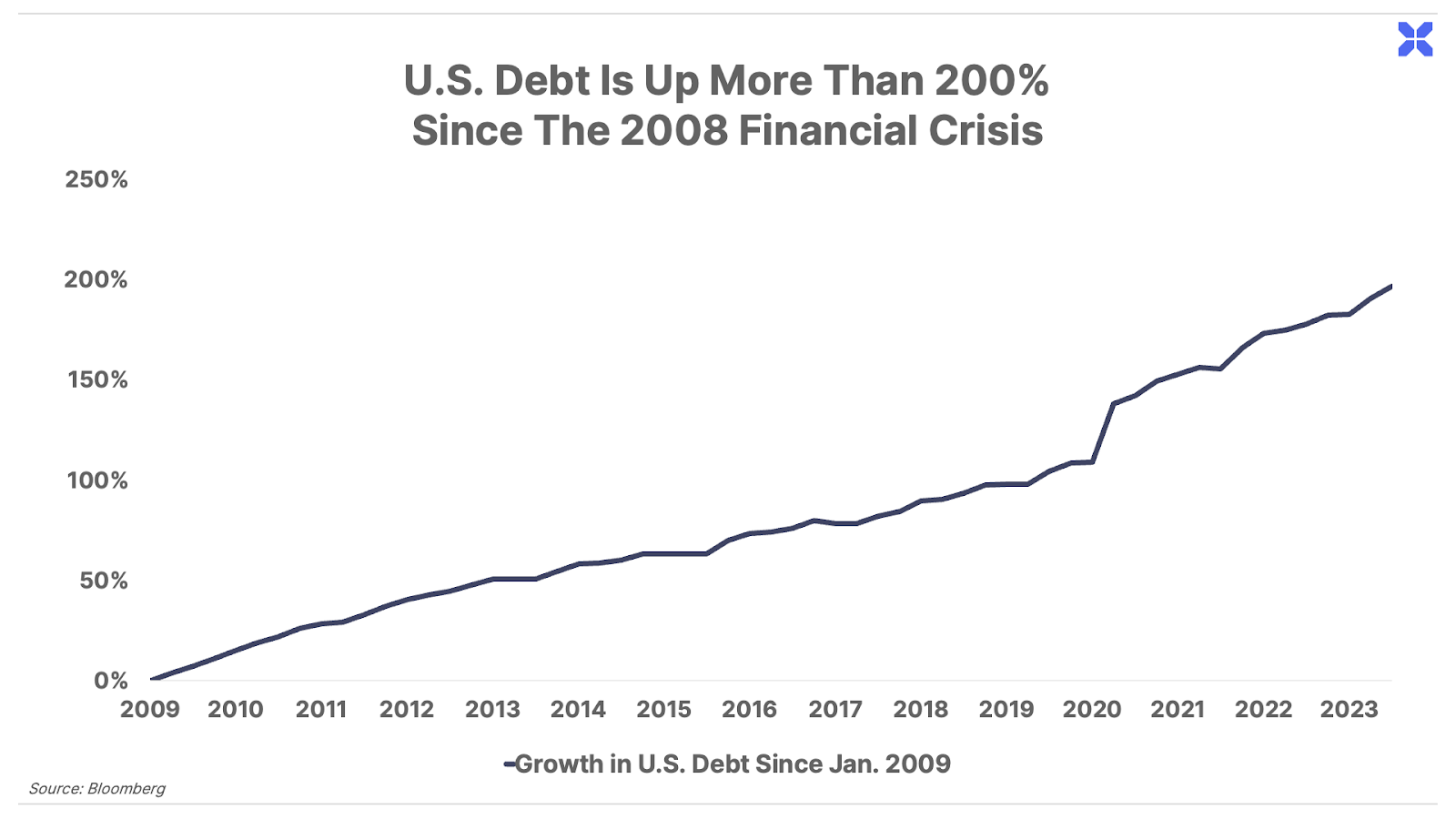

U.S. federal debt recently hit a staggering $33 trillion. That’s up an incredible $10 trillion in the last four years alone, and a more than 200% increase since the 2008 Financial Crisis. And the debt bonanza shows no sign of ending. In 2023, the U.S. federal government is on track to run a $2 trillion budget deficit, or 8% of GDP.

Outside of COVID-19, the U.S. has never run deficits this large in a peacetime, non-recessionary economy. America’s largest creditors see the same data presented here and conclude that the country’s debts can never be repaid under the current conditions. And these creditors are no longer providing the same support they once did for America’s finances.

For example, in the last few years, many of America’s largest creditors have become net sellers of U.S. Treasuries. This includes China, which Apollo Global Management estimates has sold $300 billion of its Treasury stockpile since 2021 – likely a contributing factor to the record rout in Treasury prices.

With foreigners providing less support for U.S. Treasuries, compounded by the Fed’s monetary tightening campaign, financing costs for the U.S. government are exploding. In 2022, the U.S. government spent a record $475 billion on interest alone, or roughly 10% of total U.S. tax receipts.

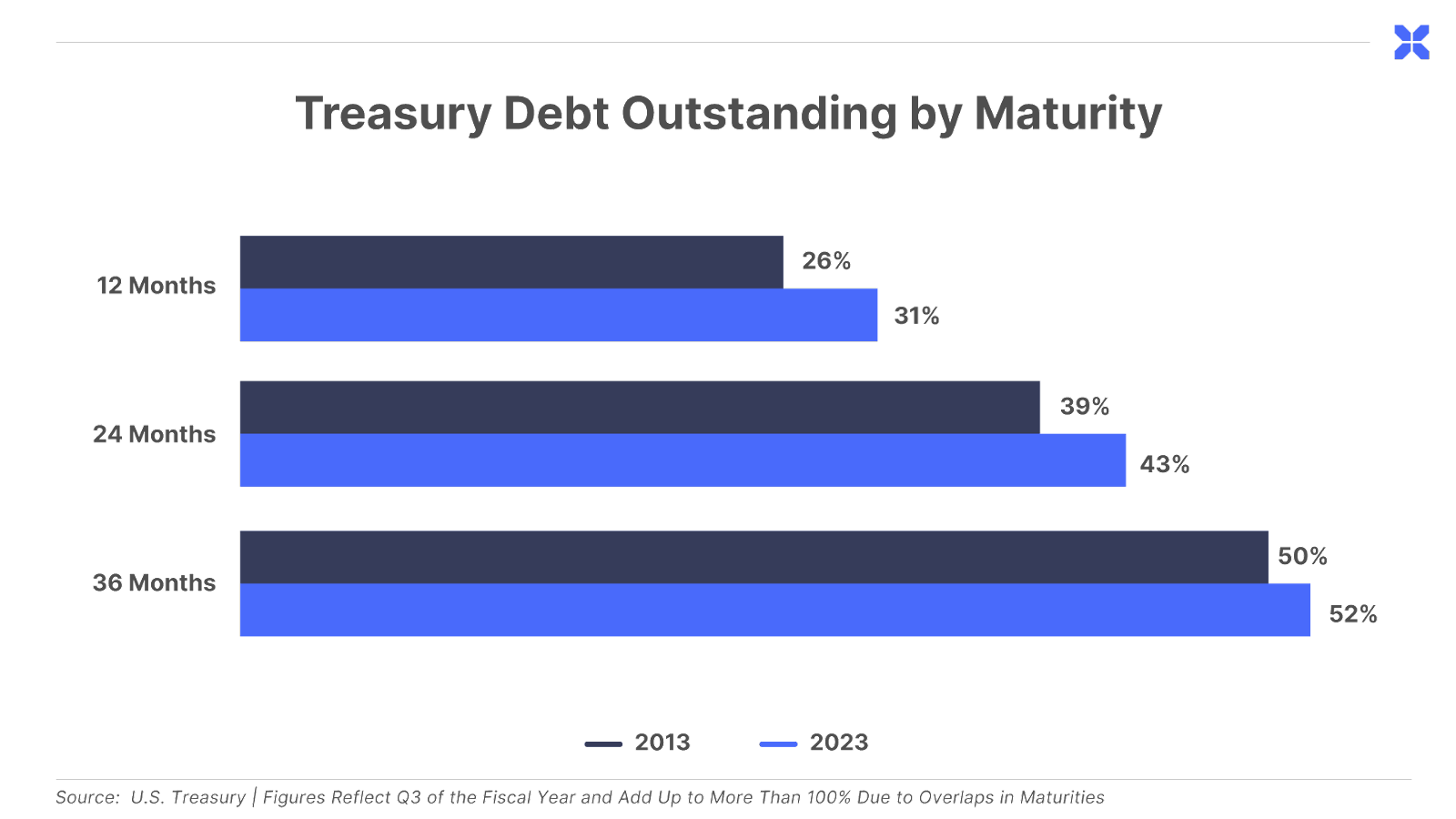

But the situation is about to become far worse. Nearly one-third of the outstanding U.S. debt is set to mature over the next 12 months. By 2026, half of America’s $33 trillion debt burden must be refinanced. And that spells more trouble.

Since this debt was last financed, interest rates on Treasuries have more than tripled, from around 1.5% to 5% today. Now, with $33 trillion in debt rolling over at 3x more expensive financing costs, this mounting interest burden will consume an ever-greater share of the federal budget.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (“CRFB”), a non-profit policy group in Washington, D.C., estimates that interest expense in the federal budget will grow to $1.4 trillion by 2033 – up from $475 billion in 2022. The CRFB projects this interest expense will continue rising, reaching $2.7 trillion by 2043 and $5.4 trillion by 2053.

By 2051, interest will make up the single largest expense of the already-mammoth federal budget. America’s spiraling debt and interest burden are approaching the event horizon – where no amount of tax increases or wealth confiscation will bring in enough revenue to repay the debts in any feasible way.

As the government continues spending money it does not have just to keep the lights on and pay interest expense, foreign creditors will increasingly unload investments in the U.S. government. As the world turns from buyers to sellers of U.S. Treasuries, the Fed will become the ultimate buyer of last resort – financing America’s runaway deficits with even more printed money.

This will be America’s final bailout, as it will lead to the loss of faith in the value of the rapidly devaluing U.S. dollar. Once the Federal Reserve crosses the monetary rubicon of endlessly financing U.S. deficits with printed money, the curtains will close on America’s status as the holder of the global reserve currency.

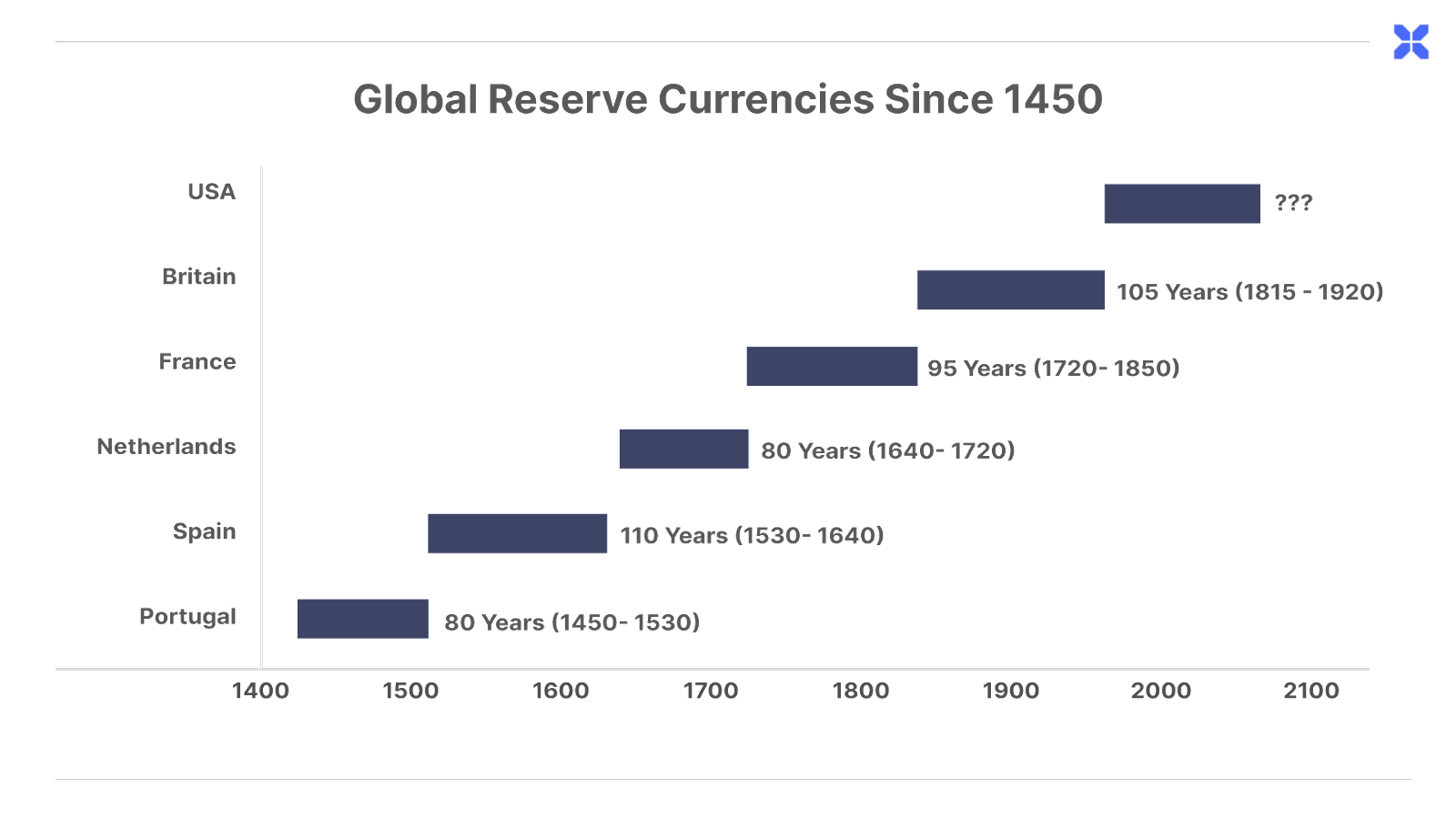

The following chart shows that the average lifespan for global reserve currencies is roughly 100 years. The dollar’s reign is just over the century mark now.

This will lead to crippling inflation, and a further unraveling of America’s social fabric. When endless currency devaluation destroys the wages of America’s lower and middle class, people will lash out.

Once the citizenry wakes up to the fact that endless government spending and money printing have made it impossible to put food on the table or a roof over their head, all bets are off. Crime, theft, and even violent revolution are on the table in this final act of the End of America.

How to Survive This “End of America” Scenario

So what’s our gameplan?

The most important thing you can do right now is to upgrade your portfolio. Take a close look at every holding and ask one simple question: are you comfortable holding this security through a financial panic? If the answer is not a resounding yes, the decision should be easy: sell and raise cash.

For the first time in 15 years, short-term Treasuries offer a real yield above inflation. Investors are no longer penalized for playing defense. That cash will become worth its weight in gold when this crisis erupts, and world-class businesses trade down to fire sale prices.

We’re putting this advice into action in our model portfolio today.

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care Concierge, Lance James, at 888-610-8895.