Foreign Powers Ditch U.S. Treasuries and Stockpile Gold

Debt “Doom Loop” Activated…

He could have been the richest plumber in London.

But instead, he chose not to crawl through the sewer to rob the Bank of England’s gold vault.

The heist would have been simple enough. It was 1836, and architect Sir John Soane had just redesigned the sprawling bank complex on Threadneedle Street. But he’d cut a few corners in the process. The stately façade of London’s central bank concealed a number of unfinished rooms and hastily sealed-off tunnels.

The architect had also overlooked a man-sized sewer pipe leading directly upwards, through the floor and into the bank’s underground bullion vault.

However, the illiterate sewer-man who discovered the secret entrance (who, legend has it, signed his name “John Smiff,” for John Smith) was just too honest for his own good.

After stumbling on the pipe while working in the nearby Dowgate sewers, “Smiff” crawled back out empty-handed. Instead of pocketing a gold bar or three, he penned a poorly-spelled letter to the directors of the bank, inviting them to meet him downstairs in the bullion vault at a time of their choosing.

Skeptically, the officials agreed to wait in the securely locked room. And at the stroke of midnight, a board moved and John’s head popped through the floor.

The flabbergasted bank dignitaries took stock of all the gold and ensured that none was missing. As a reward for John’s honesty, they gifted him 800 pounds (in bank notes, not gold) – worth around $80,000 in today’s money.

That’s the way the legend goes, anyway.

The wild tale of John Smiff first appeared in the pulpy London papers a little later in the 19th century, after the rumor mill had had time to churn. There must be at least some truth in it, because the Bank of England mentions John and his 800 pounds on its official website.

As well, historians have several surviving letters from Bank of England officials in the 1830s, warning about “dangers from the sewers” and strongly recommending that all the plans revealing sewer locations near Threadneedle Street should be confiscated and sent to the bank.

In any event, Sir John Soane’s slapdash vault designs got tightened up… and today, the Bank of England stores around 400,000 gold bars, worth a total of $200 billion, in nine secure underground vaults with walls about eight feet thick (and with no access via sewer pipes, though that has served as a plot point in several heist movies).

Much of the gold is stockpiled on behalf of around 30 other countries, and can be bought and sold by those countries and their central banks and institutions on the over-the-counter London Bullion Market, overseen by the Bank of England. About one-fifth of the total gold held by world governments is stashed under the pavement in London.

To this day (barring the alleged close call in 1836), the gold vault under Threadneedle Street has never been robbed.

However, its supply of 400-ounce gold bars has been shrinking.

A snapshot of the London Bullion Market website in 2011 indicated that the Threadneedle vaults held around 9,000 tons of gold (around 800,000 gold bars). Fast-forward to 2015, and the market mentioned in a presentation that the total was now 6,250 tons (500,000 bars). In 2024, the stockpile of bullion bars now sits at 400,000.

Where has all this gold been going? (We know it’s not down the drainpipe.)

The obvious answer is that, over an extended period of time, someone… or, a number of someones… has been purchasing gold over-the-counter on the London Bullion Market and removing it from England. These purchase records are opaque and hard to get (if you visit bullionstar.com, you’ll see some intriguing detective work on the subject).

The really important thing to note, though, is that this gold… wherever it is… hasn’t gone into general circulation. Especially recently.

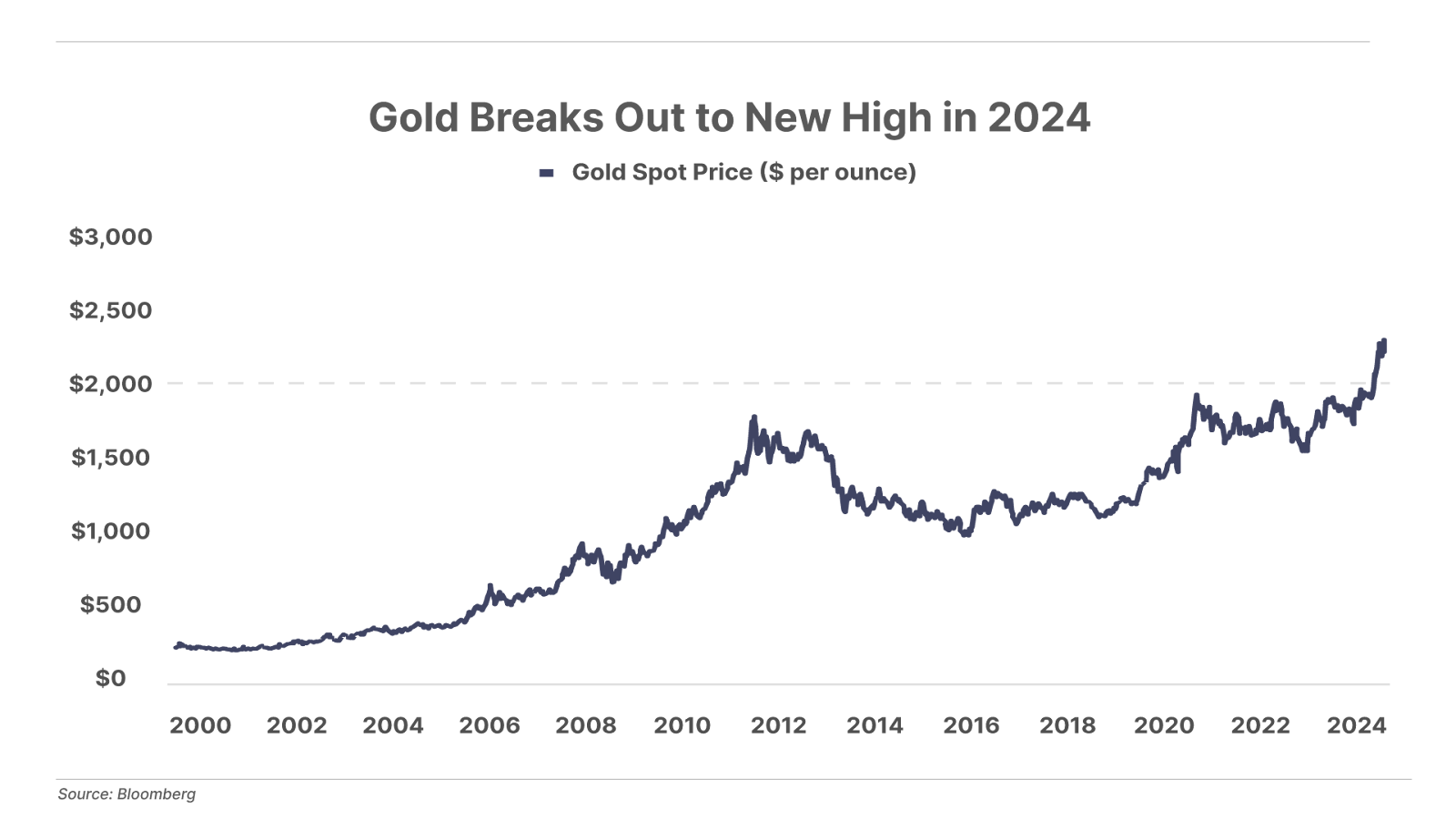

The price of gold is up 27% since October, more than both the red-hot S&P 500 (up 25%) and the technology-focused Nasdaq 100 (up 26%) in those seven months. The supply is vanishing… not just from London’s vaults, but from the worldwide markets.

Someone is buying all the gold… and sitting on it.

Who, and why?

The Gold Heist No One Is Talking About

Gold is outperforming a bull market in stocks.

Gold’s recent nearly $500-per-ounce run coincided with its breakout to all-time highs above the $2,000-per-ounce level, which had acted as overhead resistance for over a decade.

But what is particularly remarkable about this recent gold rally… is that it’s occurring with little fanfare from Wall Street or retail investors.

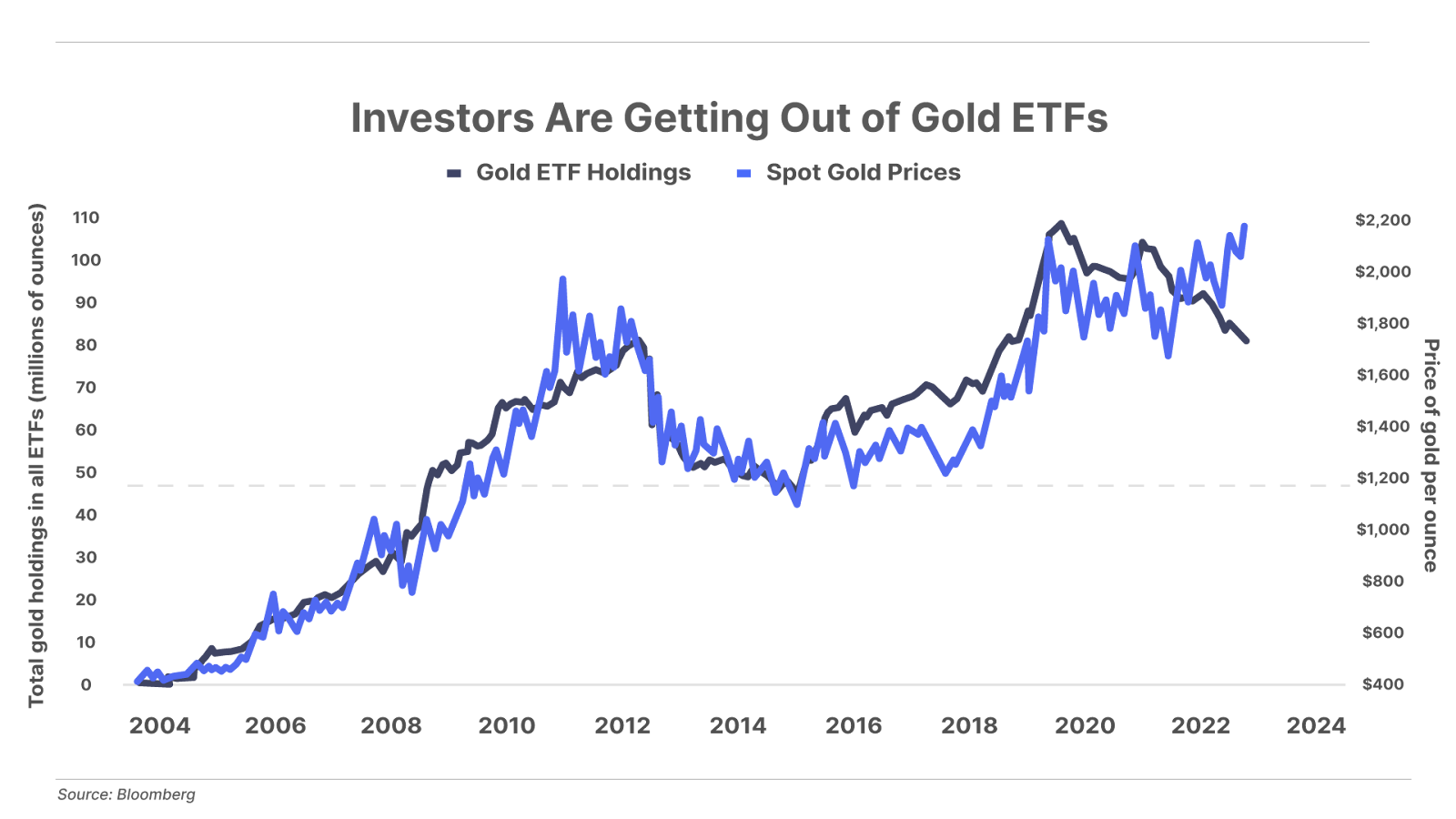

Speculative positioning in gold futures markets remains well below levels seen during big gold rallies of the past. Options-market positioning is similarly muted. Gold exchange-traded funds (ETFs) – which have become the preferred way for investors to own gold in recent decades – have actually seen significant outflows as gold has moved higher over the past couple of years. That is unprecedented.

In other words, this gold rally is not being fueled by the speculative and investment demand we’ve seen in gold bull markets of the past.

Then What (or Who) Is Driving Gold Higher?

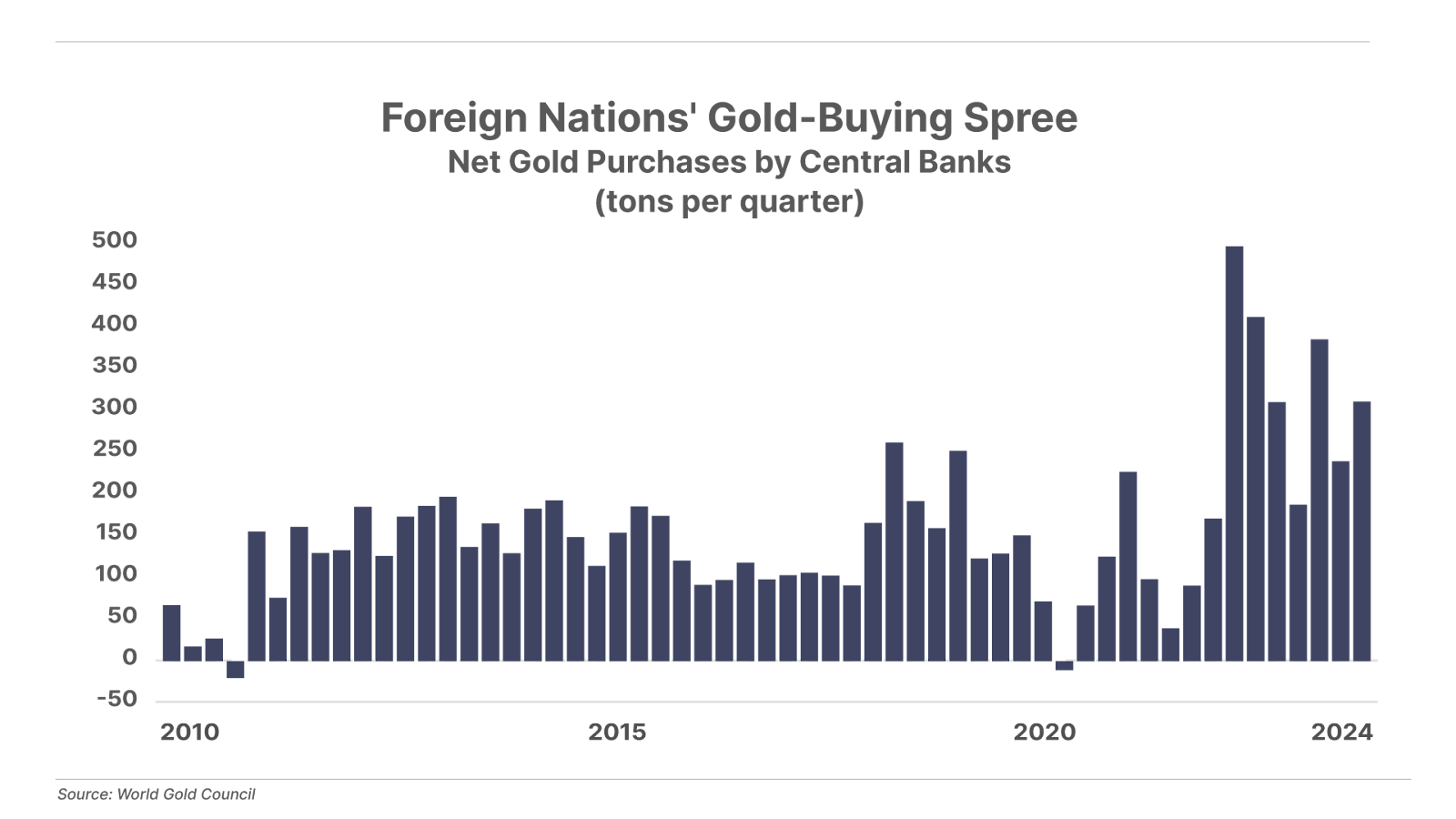

Data suggest it is foreign central banks that are buying massive amounts of physical metals and pushing the gold price higher.

As shown in the chart below, gold purchases by central banks have surged over the past couple of years.

According to the World Gold Council, central banks have added more than 2,000 tons of gold since the third quarter of 2022 – equivalent to nearly twice the average quarterly buying rate over the previous decade. Since 2022, these central-bank purchases account for nearly one-fourth of total gold demand worldwide – double the average annual demand over the prior 10 years.

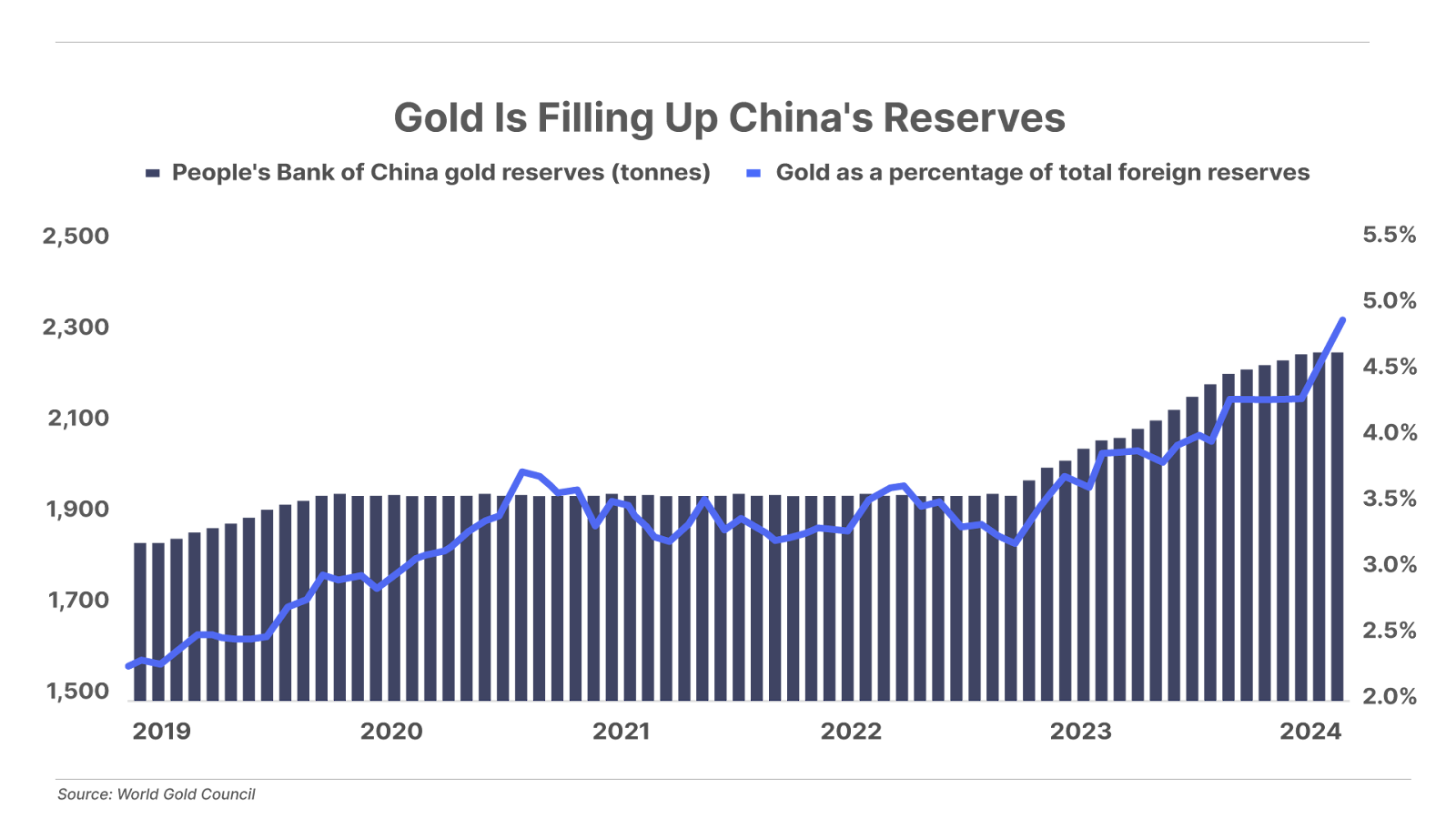

Not all central-bank buying is reported, but official statistics show that China, India, Turkey, and Russia have accounted for virtually all the central-bank buying over this period, with China leading the way… China’s official gold reserves have risen by over 20% over the past 18 months and now, as the chart below shows, account for roughly 5% of its total foreign-exchange reserves.

What’s even more noteworthy is where the funds to purchase the precious metal are coming from. The recent surge in foreign central-bank gold buying has occurred alongside a sharp decline in foreign purchases of U.S. Treasury debt.

That reality is a big deal – and might change the global economic landscape for years to come.

U.S. Treasury debt has been the world’s preferred reserve asset for decades. Foreign holdings of U.S. debt have soared from less than $100 billion in the 1970s – when the U.S. created the modern-day petrodollar system to incentivize large trading partners to begin investing their surpluses into U.S. Treasuries – to over $8 trillion today, an increase of more than 8,000%.

A decline of this magnitude has never occurred before, and here too, China appears to be leading the way…

As the chart below shows, China has been slowly reducing its U.S. Treasury holdings for over a decade. However, this trend began to accelerate in 2022, culminating in a record sale of more than $50 billion in U.S. debt in the first quarter of this year – more than 5% of its remaining holdings.

What this means is that the Chinese government is effectively selling U.S. Treasuries to buy gold.

A Shift in the Global Monetary Order

That China began upping its gold reserves and selling off U.S. Treasuries in earnest in 2022 is not a coincidence…

It was early 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. Shortly after, the Biden administration initiated severe sanctions on Russia, essentially freezing its roughly $300 billion in U.S. dollar-denominated reserves. To top it off, U.S. officials are now saying that those frozen Russian reserves might not ever be returned to Russia. Instead they could be used to fund Ukraine’s defense efforts and help rebuild the country following the war.

The message that the seizure of Russian funds sent to other large Treasury holders like China was crystal clear: Your reserves are “yours” only as long as the U.S. government deems it so. The effect was an almost immediate loss of trust in the U.S.’s role as leader of the global monetary system.

Given the severity of this move – potentially confiscating hundreds of billions of dollars from its rightful owner – it’s only natural that countries with large foreign reserves like China would seek to shift those savings to an asset that isn’t subject to the whims of a potentially adversarial foreign government. And gold – as the world’s oldest and most enduring form of money, with no central issuer and no counterparty risk – is the natural choice.

But this isn’t the only reason central banks are now looking to diversify their reserves – and get out of U.S. Treasuries.

The past couple of years have also brought a growing realization that the U.S. is on an unsustainable fiscal path. Since the COVID pandemic, the U.S. government has consistently run massive deficits, in amounts that are unheard of outside of wartime.

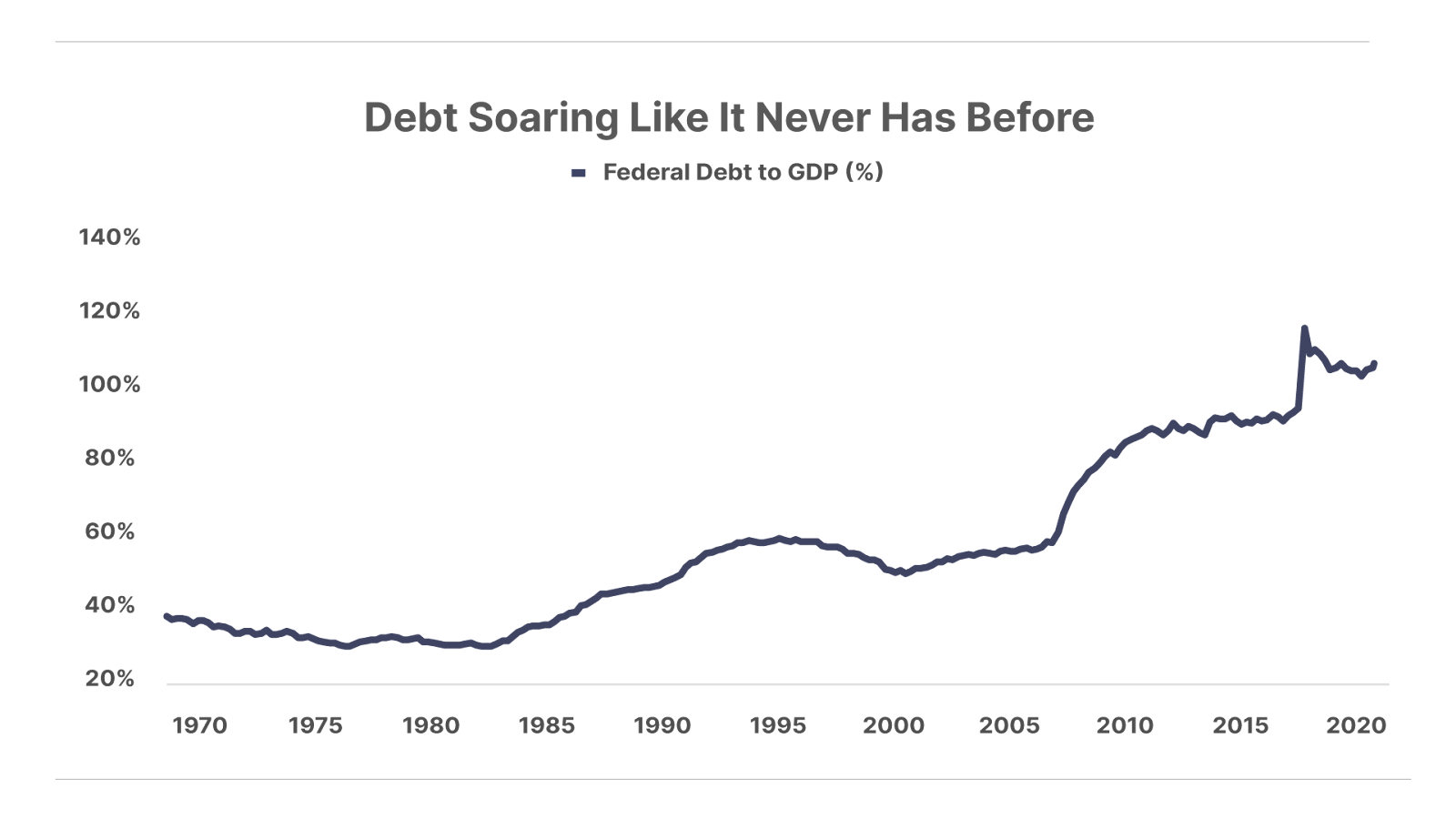

U.S. debt has soared to $34 trillion – representing more than 120% of gross domestic product (“GDP”) – and the government is adding $1 trillion to this total every 90 days. Even the relatively conservative Congressional Budget Office projects this trend is likely to continue for the foreseeable future, with debt/GDP soaring to nearly 200% over the next 30 years.

History says these debts will never be repaid in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. As we’ve noted previously, since 1800, 51 of 52 countries with debt/GDP ratios above 120% have ultimately defaulted – through some combination of currency devaluation, high inflation, restructuring, or outright default. Any of these outcomes would create significant losses for holders of U.S. Treasury debt.

(The only “exception” is modern-day Japan, where the debt/GDP ratio is currently above 200%, and has exceeded 150% since 2009. However, given that country’s recent financial troubles, it may not be the exception for much longer.)

Given this toxic combination of default risk and the threat of confiscation, countries like China would be foolish not to move their reserves out of U.S. debt. This suggests the recent rally in gold has much further to run, especially if Wall Street and retail investors eventually begin to join in on the buying as well.

Great News for Gold Is Bad News for Uncle Sam

While the continued exodus from Treasury debt is likely to drive gold prices significantly higher, it will also compound the U.S. government’s existing debt problems.

If not for the massive buying of U.S. Treasury debt by China and other central banks over the past several decades, the U.S. fiscal situation would be even more dire than it currently is.

It was this sustained demand for U.S. debt that helped fuel Uncle Sam’s profligate spending for decades without causing borrowing costs (interest rates) to rise or consumer prices to soar.

As foreign buyers continue to pull back on Treasury purchases, the government’s runaway spending is likely to cause further increases in both interest rates (already at multi-decade highs) and consumer price inflation (which has been well above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target since 2021).

This trend could trigger what economists call a debt “doom loop,” where higher rates lead to more borrowing in order to cover rising interest costs, which in turn leads to even higher rates – and this continues in a vicious cycle. Left unchecked, this would eventually result in hyperinflation or default.

Ultimately, the Fed is likely to intervene (as it has for decades) to stave off an overt crisis in the U.S. Treasury market. This scenario may involve a type of quantitative easing known as yield-curve control – which entails a central bank promising to buy an unlimited amount of bonds to hold interest rates below a maximum threshold – or some esoteric new bond-buying program hatched by those who control the purse strings in Washington.

However, while these schemes may allow the government to avoid the worst-case scenarios of hyperinflation or default, it would almost certainly lead to another huge wave of inflation as we saw following the COVID response… and a significant loss of purchasing power for holders of U.S. debt.

The simplest way for individual investors to protect themselves from these risks is to be sure to own some physical gold (as well as some “digital gold”), and to avoid owning longer-duration U.S. Treasury debt (or long-term debt of other highly-indebted sovereigns). Short-term Treasury bills – particularly those with maturities of three months or less – are generally considered “cash equivalents,” and therefore quite safe.

Beyond that, we’d also recommend investors follow good asset-allocation principles – such as those Porter and Biotech Frontiers analyst Erez Kalir shared with readers earlier this year – and continue to invest the bulk of their portfolios in the highest quality, capital efficient businesses.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD