Issue #2, Volume #1

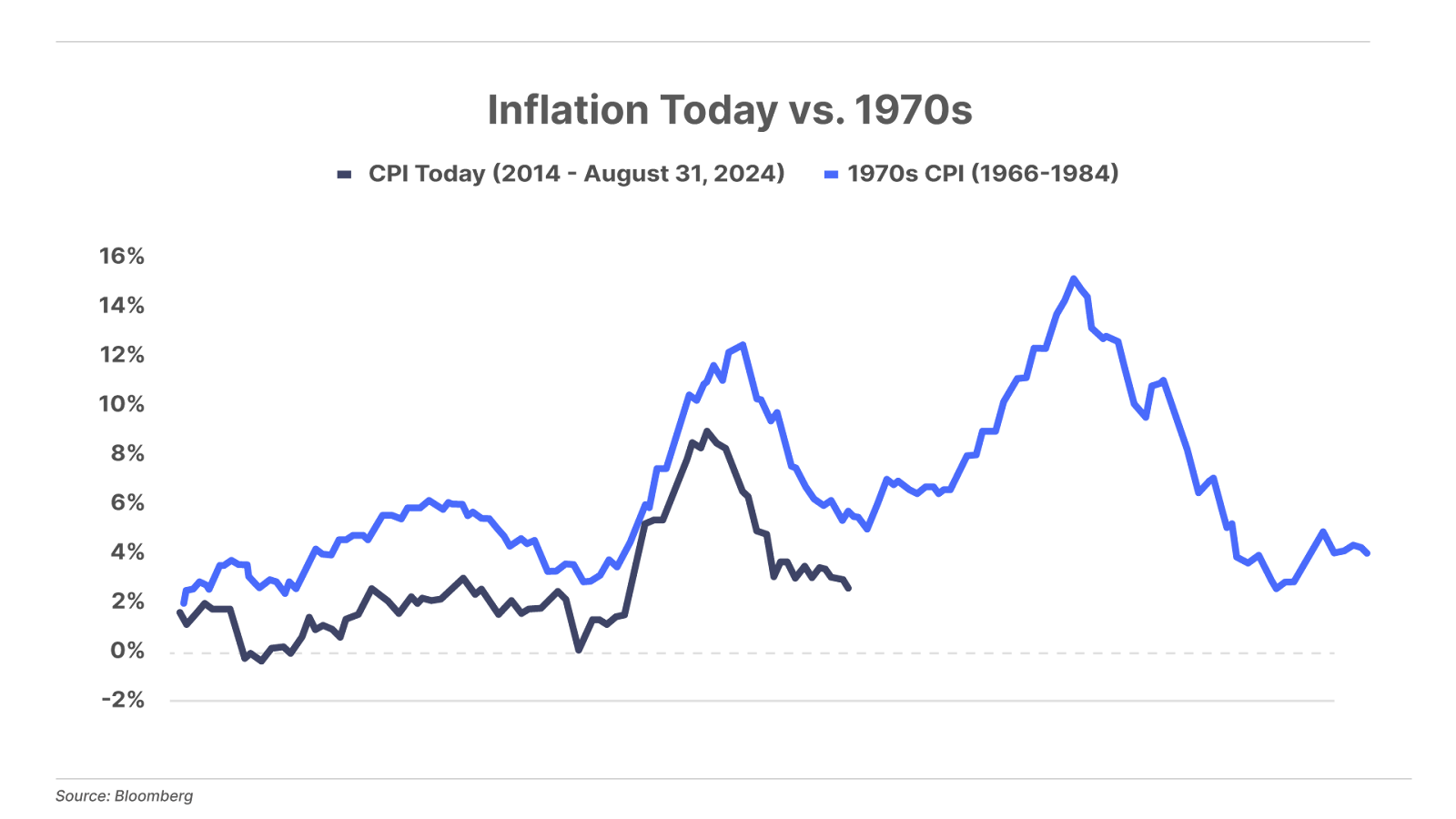

Data Out: Core consumer price index (“CPI”) month-over-month data came in hotter than expected today, up 0.3% versus 0.2%. That has put to bed the idea of a 50 basis-point cut in interest rates that the market was hoping the Federal Reserve would announce at its September 17 meeting. But we think the bigger problem (see below) is that the U.S. consumer is tapped out. Economic growth is being held up by unprecedented (in an economic expansion) government deficit spending. We are setting the stage for a 1970s-like low growth/high inflation economy. Look at this chart:

Three Things You Need To Know Now:

#1. The U.S. consumer is in big trouble. Yesterday morning Ally Financial (ALLY), which is a major issuer of consumer credit cards, reported a sharp rise in consumer loan delinquencies across the board, sending its shares down 15%. The fallout spread to Capital One (COF) and Discover Financial (DFS). Ally’s CEO hinted that it’s not only the cost-of-living crisis that is pressuring consumers, but also the growing pressures on the job market: “Our borrower is struggling with high inflation and cost of living and now, more recently, a weakening employment picture.”

#2. The Fed is way behind the curve and is at risk of causing a major financial collapse. There’s a crystal-clear sign when the Fed is making a big mistake: you’ll see the free market short-term interest rate (the 2-year Treasury note) become widely divergent from the Fed Funds Target rate, which is set by the Fed. Today, the free market rate (the 2-year note) is at 3.6%, while the effective Fed Funds rate is 5.3%. Thus the Fed is now 170 basis points (1.7 percentage points) “tighter” than the market. That’s the widest gap (the biggest mistake) since 2008. And it’s similar to the 2000-2001 tightening cycle, which led to the tech bubble collapse in 2001-2002.

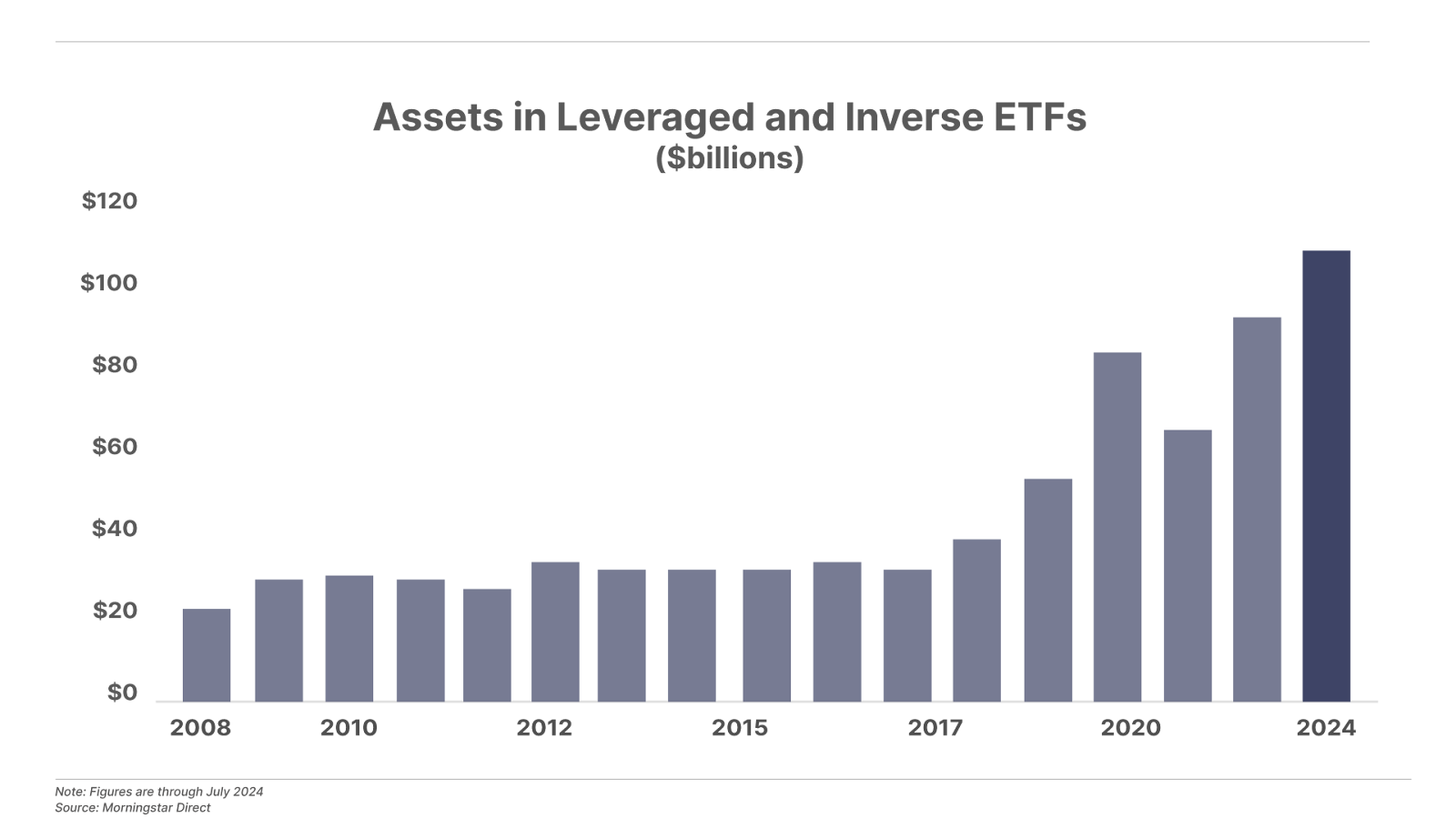

#3. A fool and his money are soon parted. One of the surest anecdotal signs of a financial bubble is speculation on margin. And today, highly leveraged ETFs have never been more popular. Do you recall what Ayn Rand taught about the poor? She said, “Don’t be one of them.” Don’t use margin when you make investments. Not ever.

And one more thing…

The tech bubble is dangerous and its collapse is nowhere near complete. Do not buy tech yet. This chart tells the whole story. No matter how much artificial intelligence (“AI”) reshapes our world and no matter how powerful the parallel-computing revolution becomes, there is no way, on average, that technology stocks can justify their current prices. This chart, from Bank of America, tells the story clearly (EV is enterprise value, a measure of a company’s total value that reflects market cap as well as debt and cash levels):

Why You Should Look for “Lindy”

An Intangible Asset You’ve Never Heard Of

Here’s an odd question for investors to consider:

Do comedians have a limited amount of humor in their brains, or is the production of humor limitless in the human mind?

This question, which doesn’t seem to be of much importance to investors, was of paramount importance to the stand-up comics of the 1960s. Stand-up comedy was booming, thanks to the emergence of national television shows, where they could be exposed to more people. But the growing demand for comics on TV led to a serious concern.

Writing comedy is extremely difficult. Performing it perfectly and getting the crowd to laugh for 30 minutes or more takes a lot of practice. Good comics might develop, test, and prove out two or maybe three hours of good material – in their entire careers. Before the emergence of TV shows, this amount of material could carry them for a long time. A comic could go from club to club in New York City, night after night, without the same audience seeing him. He could repeat the material for a long, long time. As using the same routine for years was common, most comics believed that there was a finite amount of humor in their brains. Once it was used up, they thought, it would be gone.

In New York City, local comics would gather after their sets at Lindy’s – a late-night deli at 51st and Broadway. Here they worried about this stark reality: if they took a high-paying TV gig, it would only be a matter of time before they ran out of jokes, and then their careers would be over. At Lindy’s they proposed a theory – “Lindy’s Law.” They believed the length of their careers on television would be inversely proportional to the frequency of the broadcast… that is, the more exposure to the public, the shorter their professional lifespan. It was considered career suicide, therefore, to sign up for a weekly TV show, or even a regularly monthly one. Instead, comics sought irregular specials or one-shot guest appearances.

But mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot hypothesized the exact opposite was true…

In the early 1980s, Mandelbrot famously predicted that all natural phenomena, like the talent of a human comedian, would be governed by a power law distribution. Mandelbrot hypothesized therefore, that the more frequently a comedian appeared on television, the more likely it would be for him to appear again… and again.

He defined this mathematically in his brilliant 1982 book, The Fractal Geometry of Nature.

Later, in 2012, another philosopher, Nassim Taleb, used these mathematical proofs to directly address Lindy’s Law in his book, Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder.

According to Taleb, if something is inanimate (without a natural life span), its continued usage indicates it is more likely to continue to be used. For example, if a book has been in print for 40 years, then it’s more likely than not to be in print for another 40 years. Taleb’s key insight was: things that do not have a natural life span “age” in reverse. For nonperishable things, he said, every year that passes without extinction doubles the expected lifetime.

This idea, as it applies to corporations, holds valuable implications for investors. If you’re trying to produce (or protect) wealth with common stocks, the longer the business survives and continues to compound your wealth, the better.

Looking at the past, we see that most publicly traded companies don’t survive past 20 years. They get acquired by another firm, they go private, or they go out of business.

Out of the 29,000-plus common stocks that were publicly traded in America between 1925 and today, only about 5,000 survived more than 20 years. And, as you’d expect from Mandelbrot’s work and from Pareto’s Law, which I discussed on Monday, there’s a huge “power law” in the stock market: most of the profits accrue to a very small number of companies.

Various studies show that about 1% of stocks will create about 70% of all the wealth. And what is the most important factor? Time.

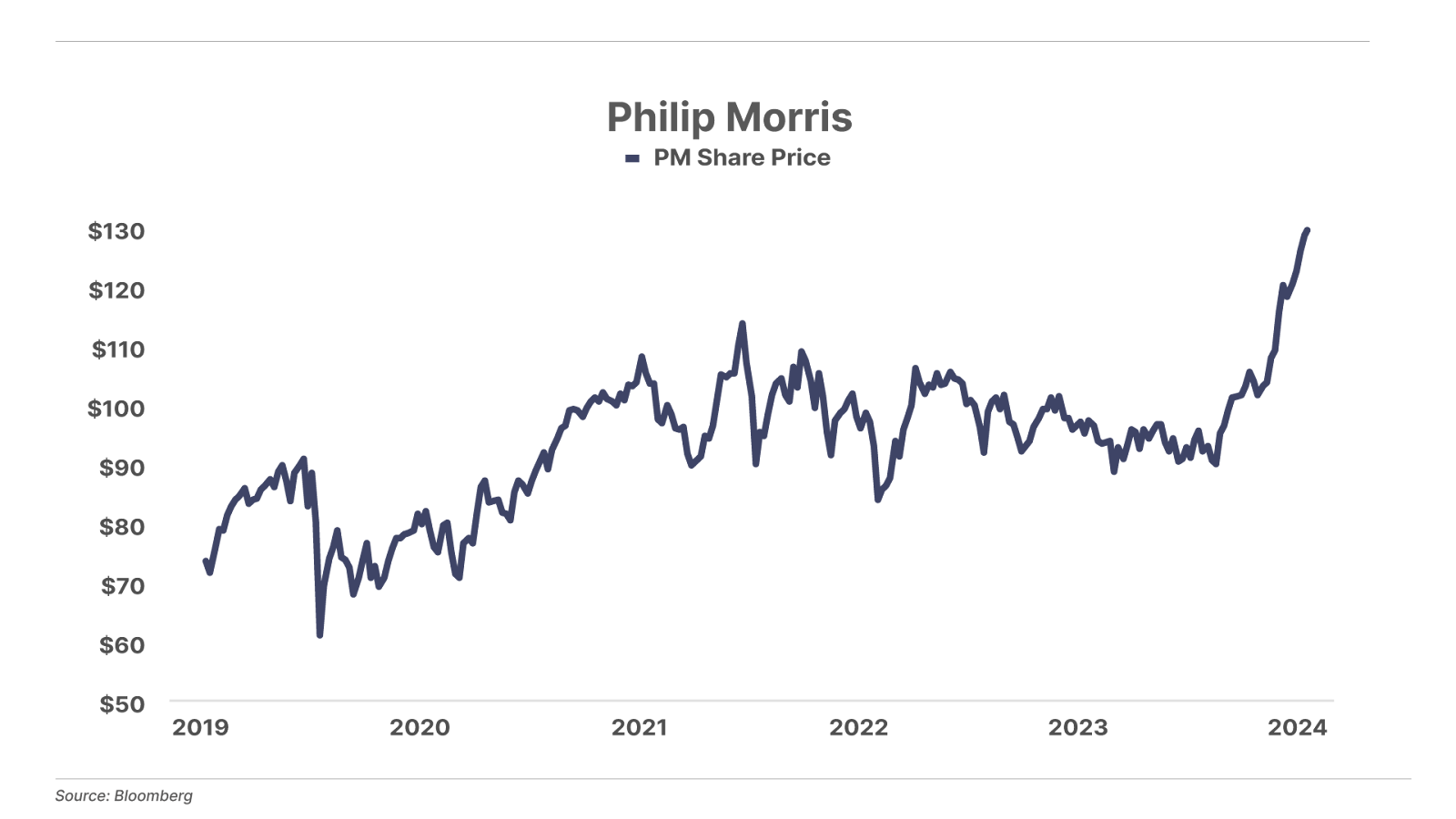

Investors in the original Philip Morris turned every $1 invested into $2.6 million from 1925 until today, a 16% annual compound return for almost 100 years. No other business even comes close to generating so much wealth. For reference, chip maker Nvidia (NVDA), which has created a huge amount of wealth, has so far “only” turned every $1 invested into $1,316, a compound annual return of 33% a year since 1999.

That’s good… but Philip Morris’ results are 2,000 times better!

That’s why I believe investors should understand Lindy’s Law and seek to own businesses that have both excellent economics and long (at least 20 year) track records. It’s these businesses that give you the best odds of producing substantial wealth.

Other notable long-term performers include (annual compound return since 1925): Vulcan Materials (VMC, 14%), Kansas City Southern (14%) General Dynamics (GD, 13% since 1926), Boeing (BA, 15% since 1934), IBM (IBM, 13%), Eaton (ETN, 13%), Coca-Cola (KO, 12.7%), Abbott Laboratories (ABT, 14% since 1937), Deere & Company (DE, 13% since 1933), The Hershey Company (HSY, 12.3% since 1927), Johnson & Johnson (JNJ, 15% since 1944), Northrop Grumman (NOC, 16% since 1951), Exxon Mobil (XOM, 11.5%), Caterpillar (CAT, 12% since 1929), Emerson Electric (EMR, 13.5% since 1944), Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMY, 12% since 1933), and Pfizer (PFE, 13.7% since 1944).

And more recent excellent long-term performers include: The Home Depot (HD, 25% since 1981), Microsoft (MSFT, 26% since 1986), and UnitedHealth (UNH, 24% since 1984).

For companies with excellent economics, a long history is a hugely valuable intangible asset – “Lindy’s Law.” Put it to your advantage.

On Friday, I’ll discuss what virtually all these great businesses have in common. And I’ll share what I believe is the biggest secret of all in investing.

And before that, on Thursday, I’ll be sending paid-up readers something very special that we’ve been working on for awhile…

This week, in The Big Secret, for the first time ever, we’re recommending a preferred stock, which is a hybrid mix between a stock and a bond, with some of the best qualities of both. And in order to talk about this unusual security properly, we’re going to have a special joint issue between renowned bond analyst Marty Fridson, who writes Porter & Co.’s Distressed Investing advisory, and The Big Secret on Wall Street.

If you’d like to sign up for The Big Secret on Wall Street before we release this issue (it’ll be at 4 pm on Thursday), just call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or (internationally) +1 443-815-4447.

Finally… to anticipate the angry rants in the mailbag…

Please, go ahead and tell me how you don’t have 100 years to invest and how all of this Lindy stuff won’t help you. Just keep in mind, Warren Buffett was born in August 1930. He began buying Coca-Cola (KO) stock following the market crash in October 1987. He was 57 years old. You can argue with me if you want, but the simple fact is, it’s never too late to buy a great business that can compound your wealth at market-beating rates. And if that’s not obvious to you, you’re probably reading the wrong newsletter.

But, go ahead. Tell me how wrong I am about all of this: [email protected]

Can Phillip Morris Return to its Winning WaysIt’s genuinely astounding how much wealth the company that began as Philip Morris & Co. has created for investors over the last 100 years. And it wasn’t all from tobacco, either. Most investors have forgotten that the company created light beer, for example.

Philip Morris bought Miller Brewing Company in 1970. And then, in 1972, Miller bought the assets of Peter Hand Brewing out of bankruptcy, including the rights to America’s first light beer, Meister Brau Lite. In perhaps the single greatest consumer product launch of all time, Meister Brau Lite was re-launched in 1975 as Miller Lite. Only two years later, in 1977, Miller Lite became the second-best-selling beer in the United States. And Miller, long an “also ran” brand, had seen its share of the U.S. beer market move from seventh place to second place.

In 2008, the original Philip Morris split into two companies: Altria (MO), which holds the company’s U.S. domestic assets. The spinoff from Altria, Philip Morris International (NYSE: PM), retained ownership of the company’s assets outside the U.S.

We’ve been recommending Philip Morris (NYSE: PM) to our subscribers almost since day one of Porter & Co. because we believe it will, once again, become a dominant consumer products company as it pioneers safe ways of enjoying nicotine. Let’s go Lindy.

Ah… The Mailbag…

No surprises here. Lots of people are grateful that I’m writing again. But some of those same people resent that I’ve asked them to pay for a subscription. Funny how that works, isn’t it? Read on if you want to learn why I left Stansberry Research and eventually started Porter & Co. And if you don’t think you should have to pay to read my work, there’s good news! Porter’s Daily Journal is free! Either way, let me know what you think: [email protected].

*** I just wanted to personally thank you. I have now joined The Big Secret. I have been following your research since the days of Pirate Investor and then Stansberry Research. I am so thrilled to be able to join The Big Secret at last. I am really looking forward to being a member and can’t wait to dive in. I am also excited to have a virtual ticket to your annual conference [which is taking place on September 25-26].. Thank you again for all you do every day to help everyday investors willing to listen to grow their wealth. Always a supporter. – Margaret G.

*** I began reading you in the early 2000s when I took a leap of faith to make what – for my circumstances at the time – was a substantial investment to become an Alliance member [at Stansberry Research]. Although I do not have a full understanding of all the machinations that occurred at Stansberry Research, I am nonetheless glad to be reading you once again. I have always appreciated your “if I were in your shoes” methodology. That said, a significant factor in the Alliance investment was the personal guarantee that it was for life. I must admit that when you announced Porter & Co., my initial enthusiasm was tempered by a feeling that it was a violation of that guarantee – simply a “rinse and repeat.” Can you help me dispel that notion? If you have been re-established at Stansberry Research, why the need to rinse and repeat with Porter & Co.? – Scott B.

Porter’s comment: Scott, I appreciate your loyalty to me, but you didn’t buy a subscription to me. You bought a subscription to Stansberry Research, a business I do not control. Although I was the founder and was a shareholder (25%) of Stansberry Research’s parent company (MarketWise), I never had a controlling interest in that business and, even now, I, personally, cannot guarantee you anything from that business.

Expecting me to be responsible for a business I don’t control… I don’t quite know how to describe it… it’s beyond frustrating.

Especially if you understand the circumstances that surround what’s happened there… so… please let me explain.

I retired from Stansberry Research in 2019 – five years ago! That is a business with 150 employees and dozens of subscription products and software tools. As far as I know, it has been serving its customers well.

For 21 years (from 1999 until 2020) I worked very hard to serve the subscribers of Stansberry Research. That might not count as a lifetime to you, but it was certainly the main part of my career. Happily, we built a great business. When I left the board in 2020, our sales were close to $500 million a year and our profits were around $100 million.

My partners and I decided that selling the company to the public was the next step for us as a business. I’m sure you can understand why we would want to do so. Access to more capital to make larger acquisitions. A liquid security to allow our major shareholder to divest. Stock to incentivize employees and to use in recruiting. I was also eager to show the world what an incredible business I’d built: our economics put us in the top 1% of all companies trading on the Nasdaq stock exchange.

For personal reasons, I decided to retire from the day-to-day writing and research of Stansberry Research in 2019. I was approaching 50 and ready to slow down. But, I planned to continue to serve as the chairman of the company.

Meanwhile, I wasn’t leaving anyone in a lurch. I’d hired several great analysts to replace me at Stansberry Research, most notably Alan Gula and Bryan Beach. The performance of my old newsletter was and remains excellent.

I understand that you’re upset that I don’t work at Stansberry Research anymore. Well, I did work there for 21 years. And I’ve tried and tried to do what’s best for the shareholders and the subscribers of that business. But the sad reality is, you never had an agreement with me as an individual. You bought a subscription to Stansberry Research and that subscription has been faithfully fulfilled.

The idea that I planned any of this — the “rinse and repeat” strategy — or that any of this in some way has benefitted me is completely ridiculous.

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, MD

P.S. What to add to a “fortress portfolio”:

This week in The Porter & Co. Spotlight, I reprinted a full issue of my long-time friend Tom Dyson’s phenomenal newsletter, Bonner Private Research. (It’s jointly written by Tom, Dan Denning, and investment legend Bill Bonner, and ordinarily, only their private subscribers would get to see it.) You can read the whole thing now, for free, here.

Tom believes there’s a massive debt crisis coming (I can’t imagine why we’re friends…), and in preparation, he’s built up what he calls a “fortress portfolio.” It includes precious metals, cash, and cheap value stocks that ideally generate 10% to 12% a year in income and capital gain. In the issue you’re about to read, he’s adding a new stock to that portfolio (a container-shipping company, of all things). You can get the full recommendation at this link.

If you’re interested in a full subscription to Bonner Private Research, Tom’s put together a special offer just for Porter & Co. readers. Details are here.