In this issue, we’re introducing a business poised to reap a windfall by unleashing the next agricultural revolution: the rise of autonomous, precision farming.

A Fail-Safe Way to Play AI

The “New Malthusians”… Foiled Again

Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email your personal concierge, Lance, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected].

At the end of this issue, you’ll find our model portfolio, watchlist (which is also here), and Mailbag — as well as a “Best Buys” section, where we’ll briefly cover three portfolio names that we think you should consider buying first.

Again… we’re excited that you’re with us…and we’re looking forward to a long and fulfilling relationship.

If you’re not a member and would like to learn more, click here.

Charles Parker was starving. And all he had to eat was bones.

It was 1845, and Parker was an inmate at the brutal Andover workhouse in England – a grim brick building where pauper families were separated (males on one side, females on the other) and set to back-breaking labor. Entrance into the workhouse was “voluntary,” but for desperately poor people, it was often their only choice – the law didn’t allow any other type of aid. Once you were in, you lost rights to vote and became, effectively, a prisoner.

And a chain-gang laborer, at that. Inmates at Andover spent long hours crushing animal bones with heavy mallets, to create nutrient-rich “bone meal” fertilizer for the agriculture industry. (Of course, the profits all went to the workhouse overseers.)

Inmates weren’t fed, either – or at least, not very much. Colin McDougal, the crooked superintendent at Andover, routinely docked workers’ rations in order to pad his own pockets. Grown men had to get by every day on just a hunk of bread and a bowl of gruel. And so eventually, Andover workers started gnawing on the bones in the fertilizer room.

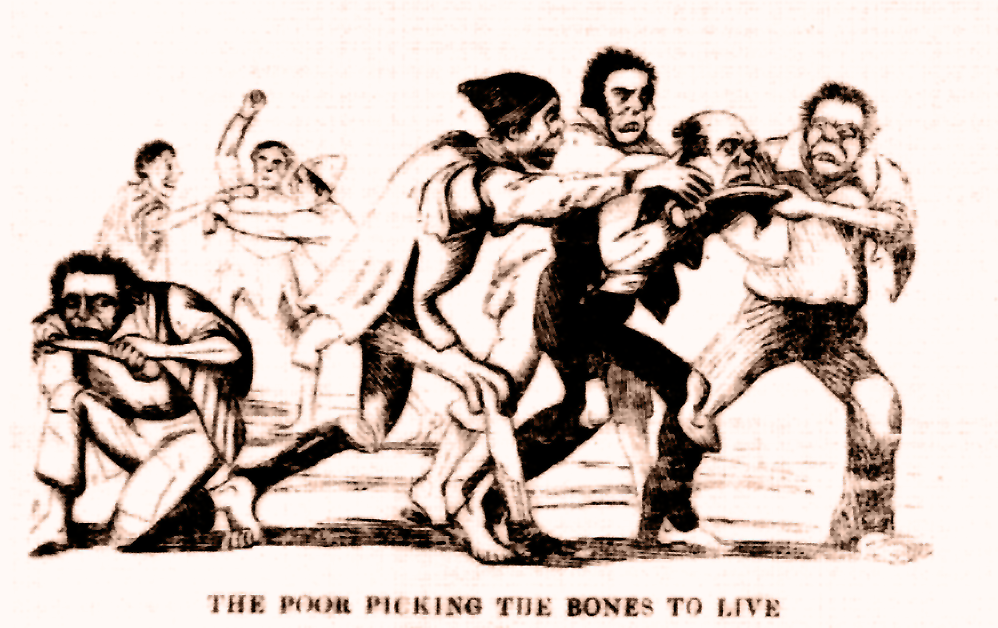

As the Victorian public discovered when the “Andover scandal” made headlines in 1845, the starving men assigned to “bone-crushing” duties would fight over fresh bones, and even suck the marrow out of rotten ones. Charles Parker – who later gave testimony in court – said he was “extremely hungry,” but couldn’t eat the bones because his “stomach wouldn’t take it.” The smell, he explained, was “very bad.”

Outrage notwithstanding, bleak conditions at workhouses like Andover – said to be the inspiration for Charles Dickens’ dark novel Oliver Twist – were largely by design…

England’s stringent 1800s “Poor Laws” – which broke up poor families and locked them in institutions, simply for being destitute – were directly inspired by the population-control theories of doomsday economist Thomas Malthus. In Malthus’s seminal 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population, he argued that exponential population growth would soon outstrip Earth’s natural resources, leading to famine, starvation, and death. Supporting his argument at the time was the fact that the amount of arable land available for crop production was shrinking measurably.

Malthus’s solutions to overpopulation were bleak. He suggested that only “misery,” war, and artificially lowering the birth rate could keep numbers in check. These ideas eventually spurred England’s legislators to create the “workhouse” – a cruelly effective way to starve the “less-desirable” population, keep them from breeding, and save resources for worthier people. (Sounds a bit like eugenics? You’re not wrong.)

Dickens’ most famous character, the notoriously stingy Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, expresses classic Malthusian philosophy (before he encounters the true spirit of Christmas, that is). On hearing that many poor people would rather die than enter workhouses, Scrooge retorts, “If they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Viewed through the lens of today – as well as of the times – Malthus’s ideas are abhorrent. And (surprise) they don’t work…

England’s draconian Poor Laws (and its workhouses) did nothing to improve the country’s economy. A 2018 academic study concluded, “This deliberately induced suffering gained little for the land and property owners who funded poor relief. Nor did it raise wages for the poor, or free up migration to better opportunities in the cities. … [T]he Poor Laws … consequently had no effects on economic growth and economic performance in Industrial Revolution England.”

What does improve economic performance? Human ingenuity and intelligence. (Oh, and capitalism.)

Mechanized farming… not eugenics… eventually solved the “shrinking farmland” problem. Throughout the 1800s, a growing array of new tools and machinery – the mechanical reaper, the grain elevator, the mowing machine – enabled farmers to produce more crops per acre of land with each passing year. And as farmers spent less time hunched over plows and rakes, labor moved from the fields to the factories and fueled the Industrial Revolution.

Two centuries after An Essay on the Principle of Population first appeared, the world has ample crops, shelter, and resources to support an additional 7 billion people. Sorry, Malthus. We are not running out of food.

But try telling that to the climate change zealots…

Today, you can spot Malthusian ideology coming from organizations like the World Economic Forum (WEF). Made up of today’s global elite, the WEF argues that traditional agricultural production consumes too much land, water, and fuel. And this excess resource consumption is contributing to climate change, which will supposedly also reduce future agricultural output. The WEF website claims that the world will fall short of traditional crop and animal-based proteins by 2050:

“We’re actually running out of protein. By 2050, the earth will have nearly 10 billion people. The demand for protein will exceed our ability to procure it. That’s a scary thought.”

Their solution? Let them eat bugs. No, seriously, that’s an official recommendation from the WEF, which advocates insects as an alternative food source to fight climate change:

Internationally funded climate organizations are making their way into the policy discussion at the local level. The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, which includes 14 U.S. cities, is advocating restrictions in meat consumption, private clothing, and personal transportation. A 2019 press release from the C40 group states:

“Cities, businesses, restaurants, farmers and citizens need to work together to help people cut their meat consumption by two-thirds, for example eating meat just two days per week rather than every day.”

The idea that humans must cut back on their living standards in the name of “climate change” is the same scarcity mindset the Malthusians introduced more than 200 years ago. It assumes that human beings can’t devise new methods of energy and crop production that increase output while minimizing environmental impact.

Call us optimists, but we’re taking the other side of that bet.

Porter Stansberry has been betting against the Malthusian mindset for more than two decades. Perhaps most famously, he predicted the fallacy of peak oil as far back as 2006. Back then, the consensus on Wall Street said that the world was running out of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, Porter was writing about the incredible new shale drilling technology that would unleash an unprecedented boom in American oil and gas production.

Subscribers who followed his work reaped a windfall as America became one of the world’s largest exporters of cheap shale oil and gas.

Today, we’re introducing a business poised for similar upside by unleashing the next agricultural revolution: the rise of autonomous, precision farming.

This company’s game-changing new artificial-intelligence (AI) technology will transform the productivity and resource management of modern-day farms. This tech will not only help farmers become more productive, but it will dramatically reduce the environmental impact of crop production. (Perhaps most importantly, this means we won’t have to resort to eating bugs to feed the world’s growing population.)

For close to two centuries, this company has led its industry in delivering productivity-boosting technology on American farms. It’s the dominant market leader today, with premium pricing power and best-in-class profit margins. Shares of this business have consistently compounded capital at 15% to 20% annually for decades. And we see even more upside ahead, as the company benefits from higher-margin software sales that will transform the modern-day farm.

Unlike most AI-focused stocks in today’s market, investors have largely ignored this opportunity. This world-class business today trades at just 13x earnings – compared with nearly 50x earnings multiple for Nvidia (NVDA), the epicenter of today’s AI enthusiasm.

To begin, let’s rewind the clock to see how the company first established what became one of the most enduring brands of all time.

Planting the Seeds for Long-Term Profits

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.