Groupthink Has Once Again Led Us Into a Bubble

…And An Unexpected Pin May Pop It

For the past several weeks in The Big Secret on Wall Street, we’ve detailed the technological transformation that is driving artificial intelligence (“AI”), machine learning, and so much more. We call this big story The Parallel-Processing Revolution.

In honor of Porter & Co.’s second anniversary, we’re making this vital series free to all our readers. You are getting a high-level view of this tech revolution and receiving several valuable investment ideas along the way. However, detailed recommendations and portfolio updates will be reserved for our paid subscribers. If you are not already a subscriber to The Big Secret on Wall Street, click here…

Here are links to the first four issues of the series:

- Part 1 explains how chipmaker Nvidia led the industry switch to parallel computing

- Part 2 chronicles two near-monopoly companies that power chipmaking globally

- Part 3 compares current investment opportunities with the internet boom 25 years ago

- Part 4 highlights the company that’s developing the “brains” that power the Parallel-Processing Revolution

“Stop asking questions about your son.”

Startled, Mary Lou Ray looked across the breakroom at her newest coworker, a nondescript little man who’d just started working with her at JCPenney that morning.

How did he know who she’d been talking to… or what she’d been saying?

“If you ask anyone about the Bay of Pigs again,” he hissed, “you’ll be in trouble.”

It was April 1961, and Mrs. Ray’s 31-year-old son, Captain Pete Ray – a member of the Alabama Air National Guard – had recently disappeared without a trace, leaving behind a wife and two young children.

Rumor had it that Pete was mixed up in the recent, unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro’s Communist dictatorship in Cuba. But the U.S. government steadfastly denied that they’d sent any American troops to storm the Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs), or that the U.S. was involved at all.

Not surprisingly – since the Bay of Pigs invasion turned out to be a complete disaster.

And it seemed that someone didn’t want Mary Lou Ray asking inconvenient questions.

The “official” story about the Bay of Pigs invasion was as follows: Cuban nationals planned to rebel against recently installed dictator Castro. Their agenda: Attack the Bay of Pigs airstrip on the southern coast of Cuba, bomb and disable Castro’s air force, and then march on the capital, Havana. They’d inspire their fellow Cubans to join them, and in no time, the Communist regime would be toppled from “within.”

In reality, the Bay of Pigs invasion was a completely U.S.-planned operation, with planes, weapons, funding, combat training, and National Guard assistance for a small army of Cuban expats – all organized by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Many Cubans hated Castro’s regime – and the U.S. government saw an opportunity to use that hatred as a tool to take down their own political enemy.

The plot was top secret… until it flopped miserably.

Due to a series of miscommunications, the U.S. only sent in eight B-26 bomber planes instead of the planned 16. Instead of wiping out Castro’s entire air force, the small group of B-26s destroyed only about half of the fleet – which meant Communist forces were ready, locked and loaded when the second part of the invasion, the ground troops, arrived.

The waiting 20,000 Communist soldiers ate 1,400 U.S.-backed Cubans for lunch.

About 1,200 of the unlucky Cubans were taken prisoner, and the rest were killed… along with American National Guard member Pete Ray, whose body was just abandoned in Cuba since, officially, he’d never been there at all.

The whole fiasco was over in just three days, kicking off a heavy-handed cover-up by the Kennedy administration of what would come to be known as one of the greatest foreign policy blunders of all time.

Three government spooks in a shiny car informed Pete Ray’s family that Pete had “died in the Caribbean Sea”… but wouldn’t give his relatives any straight answers, or send a body home. Increasingly frustrated, Pete’s mother went to question the general in charge of the Alabama air base where her son had last been seen.

The general didn’t have any answers for her, either… but the next day, a mysterious little man showed up to threaten Mrs. Ray at JCPenney.

He shadowed her for a few more months until she quit her job. Then, he quit, too.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, when a number of CIA documents were declassified, that America’s involvement in the Bay of Pigs debacle fully came to light. And it would be many more years before Pete Ray’s body would be located in a Cuban morgue, returned to his family, buried with full military honors, and posthumously awarded the Intelligence Star, the CIA’s highest honor, in 1998.

And, over the years, as more Bay of Pigs documents surfaced, the most curious part of the story emerged…

Brass Delusion

Kennedy’s war room was a close-knit group of about 50 brilliant minds, including renowned historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., lawyer and intelligence director Robert Dulles, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. They were all passionate about stopping the Communist threat to 1960s America… so passionate, in fact, that it overrode their good sense.

It turned out that several of the top brass – including President Kennedy – thought the secret Cuban invasion was a bad idea from the get-go. And yet no one spoke up and said anything. JFK had inherited the plan… along with many top advisors… from his predecessor in office, Dwight D. Eisenhower – and he felt pressured to continue with the increasingly complex operation.

Schlesinger recalled that “senior officials… were unanimous for going ahead… Had one senior advisor opposed the adventure, I believe that Kennedy would have canceled it. No one spoke against it.”

“There were 50 or so of us, presumably the most experienced and smartest people we could get,” Kennedy said later. “But five minutes after it began to fall in, we all looked at each other and asked, ‘How could we have been so stupid?’”

It was a kind of mass delusion… a state of collective denial. And it fascinated social psychologist Irving Janis so much that he wrote a book about it.

As more details on the Bay of Pigs story came to light, Janis wrote and revised his now-classic text, Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Janis used the Bay of Pigs and several other high-level political disasters to examine the madness of crowds. And he laid out his central theory, the now-familiar concept of “groupthink”:

I use the term groupthink as a quick and easy way to refer to the mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence-seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive ingroup that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action.

In many ways, groupthink works like Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale, “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Individuals within the group may notice something is wrong – but as long as group consensus chooses not to see the naked emperor, no one will say anything.

Often, disaster follows.

Once you start looking for groupthink… symptoms of which, Janis says, include the illusion of invulnerability, the collective rationalization of group decisions, and stereotyping of opponents… you see hints of it everywhere.

Not just in top-secret Oval Office meetings (or, in the collective agreement to pretend certain elderly politicians aren’t frail and ill)… but in markets, too.

The Future Is (Not) Now

In each of the major asset bubbles we’ve witnessed in recent years… the dot-com bust, the mortgage crisis, and now, the rapidly expanding AI mania… we notice a loud cohort chanting the classic market refrain, “this time is better.” And outside that group, a few lone voices saying, “hang on a sec.”

Possibly, there are a lot more quiet voices who are afraid to disagree with the consensus and speak up… until it’s too late.

Of course, market “groupthink” isn’t as clean-cut as a single policy directive from a Presidential brain trust. We’ll always have a plurality of voices and beliefs as long as the airwaves and the internet are free.

But right now, it’s worthwhile asking if the market’s obsession with all things AI shows any of the telltale signs of groupthink, and if one day soon investors will find themselves asking, as did President Kennedy, “How could we have been so stupid?”

Over the past several weeks, we’ve explained how The Parallel-Processing Revolution – led by Nvidia and a handful of other critical technology companies – will transform the global economy in the years ahead… and create generational wealth for savvy investors along the way.

This revolution will extend well beyond artificial intelligence. We believe it will ultimately change the very concept of what a computer is, enabling all kinds of incredible new technologies – such as self-driving cars, human-level machine interfaces, and advanced robotics – in addition to products and services we can’t even imagine today.

However, we’ve also warned Big Secret readers that this transformation won’t happen overnight. The revolution will take a decade or more to fully develop… and overeager investors going “all in” now on this early speculative mania are likely to regret it.

That’s because the recent boom in Nvidia and related stocks has centered almost exclusively on one parallel-processing application in particular: a subset of AI known as generative AI, or “gen AI.” And unfortunately for investors, gen AI has some serious shortcomings…

Gen AI Appears to Have a Groupthink Problem

In simple terms, gen AI models identify patterns and structures within existing data to generate new content in the form of text, images, sounds, etc. Large language models (“LLMs”) like ChatGPT are among the best-known examples of gen AI.

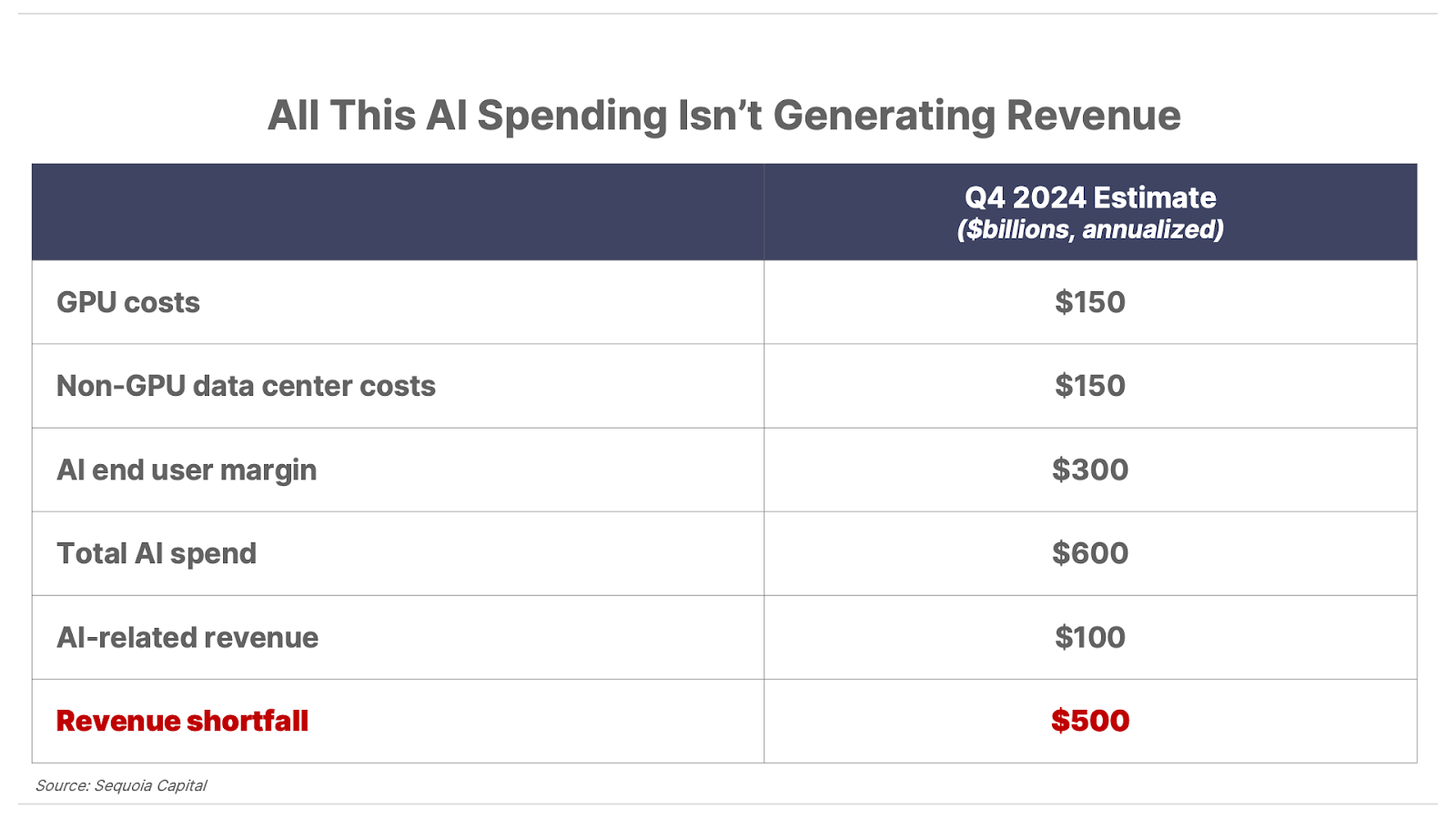

Gen AI applications have accounted for the vast majority of the roughly $167 billion spent over the past 18 months on graphics processing units (“GPU”) – the high-powered chips supercharging the parallel-processing revolution. And companies continue to ramp up spending: by the end of 2024, Nvidia alone will be generating revenue from GPU sales at an annualized rate of $150 billion.

Because of the potential scale of what AI has to offer, many players are trying to get into the game. These include the Big Tech firms spending all those billions on GPUs, Wall Street analysts and financial media pundits hyping the trend, and fund managers and individual investors bidding up the shares prices of Nvidia and other AI-related stocks to new highs. Not to mention every entrepreneur with a tech background and a dream raising funds for their AI-related startups. For the most part, they have all largely been ignoring a couple of inconvenient truths.

In short, despite this massive spending on gen AI infrastructure, companies have seen a relatively small return on those investments. And contrary to the hype predicting gen AI would transform “knowledge work” and usher in dramatic increases in productivity across dozens of industries, gen AI models have thus far had little impact on the broad economy – and demonstrated relatively few transformative use cases.

And it appears the market may finally be starting to wake up to these realities…

The AI Backlash May Now Be Underway

In just the past weeks we’ve seen a notable wave of gen AI skepticism emerge from Wall Street and the mainstream financial media. And though the specific arguments differ, all have highlighted these two critical problems in particular.

For one, a late June report from venture capital giant Sequoia Capital suggests that AI firms in aggregate would need to generate a total of $600 billion in revenue this year to justify their current annual AI capital expenditure (“capex”) rates. The table below summarizes Sequoia’s findings using chipmaker Nvidia’s GPU sales, average data center operational costs (energy, backup generators, etc.), and typical margins for AI end users (the businesses actually making use of this infrastructure spending in their AI applications).

Yet, even the rosiest estimates suggest firms are likely to generate no more than $100 billion in new AI-related revenue this year, leaving a $500 billion shortfall in needed investment returns for each year of capex at current levels.

A recent report by global investment bank Barclays compared this apparent overspending on AI infrastructure to the dot-com boom, when companies invested billions installing fiber-optic cable that wouldn’t become economically viable for a decade or more.

And perhaps most notable, investment bank Goldman Sachs – which as recently as May was still making a bullish case for gen AI – has now turned cautious as well. Head of Global Equity Research Jim Covello sums it up nicely in a June 25 Goldman report…

My main concern is that the substantial cost to develop and run AI technology means that AI applications must solve extremely complex and important problems for enterprises to earn an appropriate return on investment (ROI). We estimate that the AI infrastructure buildout will cost over $1tn in the next several years alone, which includes spending on data centers, utilities, and applications. So, the crucial question is: What $1tn problem will AI solve?

… While the question of whether AI technology will ever deliver on the promise many people are excited about today is certainly debatable, the less debatable point is that AI technology is exceptionally expensive, and to justify those costs, the technology must be able to solve complex problems, which it isn’t designed to do [today].

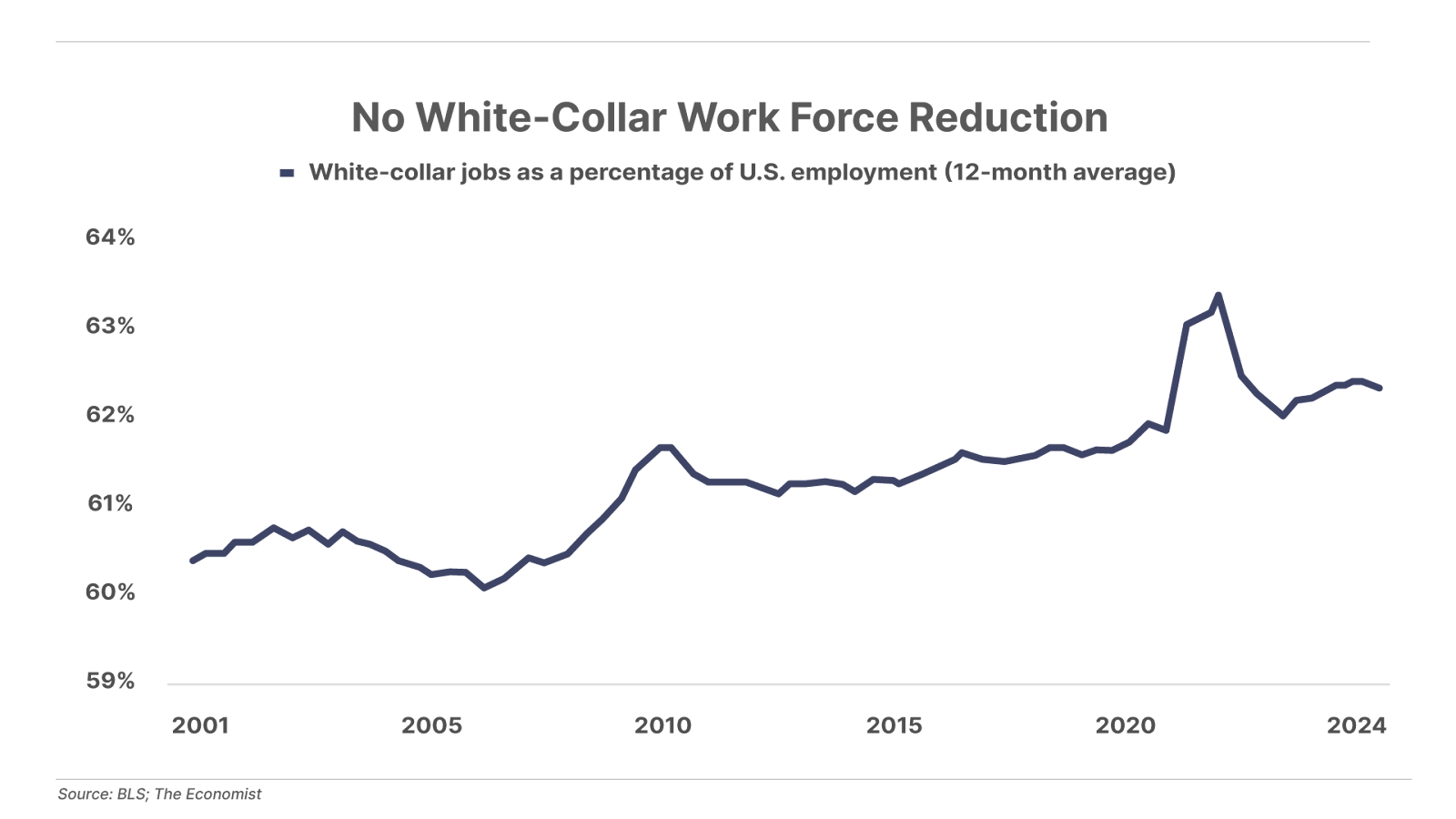

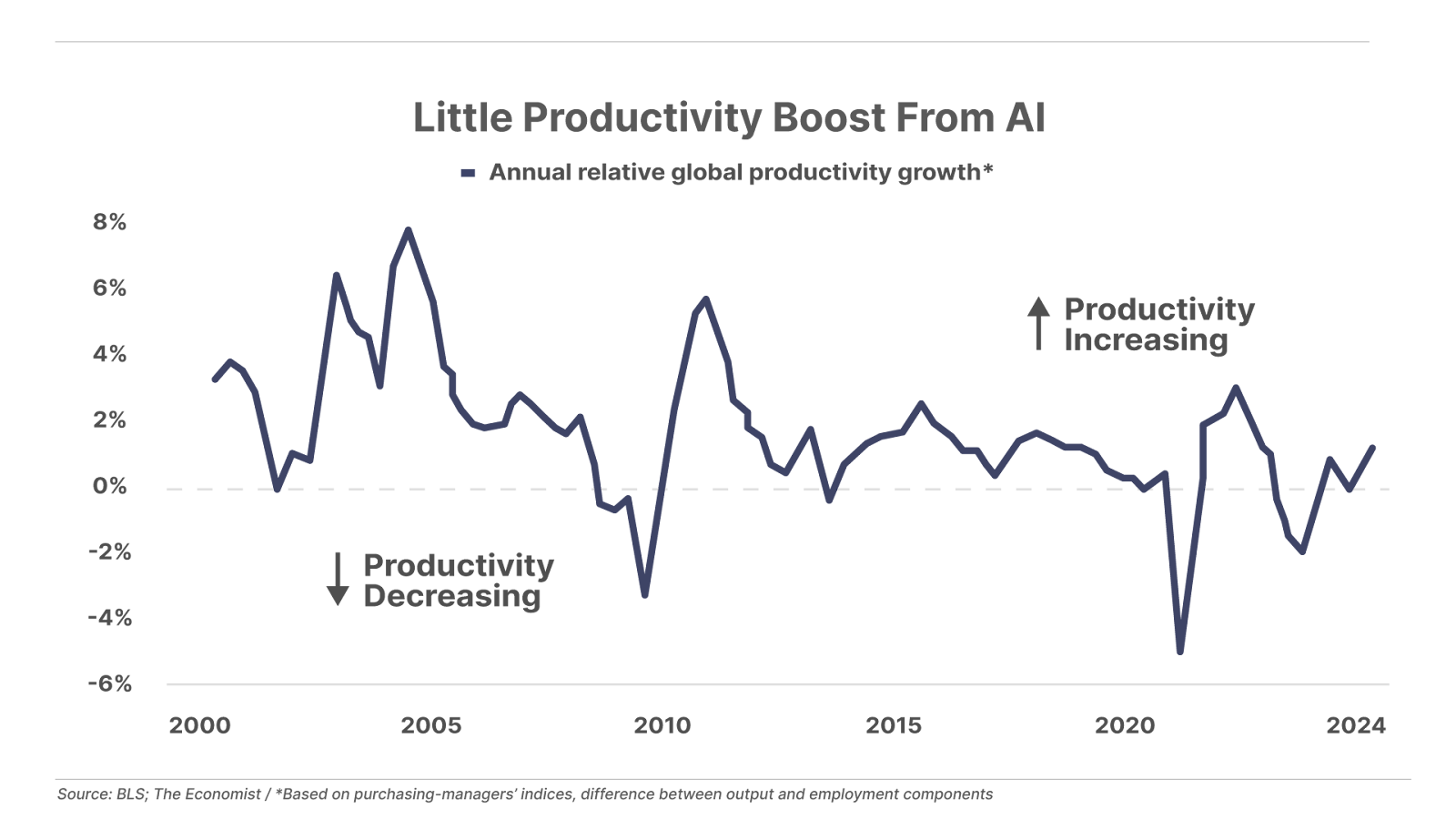

Secondly, a July 2 article in The Economist highlighted the fact that gen AI has thus far failed to deliver any obvious economic benefit as well.

If it had, we would expect to see some signs of weakness in the white-collar job market or a meaningful increase in measures of global productivity over the past couple years. Yet, as the charts below show, white-collar employment remains relatively strong, and productivity growth remains tepid.

Those fueling this mania for two years now are beginning to realize that AI is not boosting productivity or reducing labor costs as promised. Some stocks are riding high, but with little current or future revenue to support those valuations, those share prices are tenuous. All that’s needed for a wide-scale collapse is a catalyst that causes market participants to rush for the exits.

As we’ve discussed, this catalyst could be a recession that forces tech firms to dramatically pull back on AI spending… or (worse), a flare-up in tensions between Communist China and neighboring Taiwan, the island nation where the vast majority of GPUs are produced.

But it could also be something far more benign…

Is Apple the Pin That Pops the AI Bubble?

For the past 18 months, AI bulls have dismissed concerns about the actual usefulness of gen AI technology, and the economic impact its having for businesses, with reassurances that, sooner or later, the industry would find its “killer app” – a use case that would make gen AI exciting and indispensable for consumers.

When Apple (AAPL) unexpectedly announced a partnership with ChatGPT creator OpenAI at its annual Worldwide Developers Conference in June, hopes soared that the iPhone creator would be the company to bring on that killer app.

AAPL shares rallied more than 20% since the announcement – adding more to the company’s market cap in roughly six weeks than electric vehicle maker Tesla (TSLA) is currently worth – as investors imagined the partnership could unleash exciting new AI features and drive more iPhone sales.

However, as more details have emerged, we anticipate that this deal could be a huge disappointment in the end.

That’s because Apple’s AI features themselves are arguably underwhelming… consisting primarily of a “smarter” version of its Siri virtual assistant that essentially offloads requests to ChatGPT when it can’t figure out an answer itself – along with some personalized emojis and productivity tools. Apple Intelligence – as the company is calling it, cleverly capturing the AI acronym – certainly doesn’t appear to be the killer app many have been waiting for.

When considered alongside a saturated smartphone market and growing signs of financial strain among many consumers, these features seem unlikely to drive a big iPhone upgrade cycle.

And if generative AI fails to gain traction even on the world’s most popular smartphone, it could further highlight just how far this technology has to go to be useful.

Given these downside risks, we continue to urge Big Secret readers to remain conservative with all parallel-processing-related stocks today. When this speculative mania eventually ends, patient investors will have the opportunity to purchase the companies that are actually driving this revolution, at a fraction of their current valuations. Thus avoiding having to answer the question that so many will likely be asking: “How could we have been so stupid?”

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD