The Hidden Risks Of This Very Big Bank

What Every Investor Should Know… And Do

| Below is this week’s Big Secret on Wall Street… We are making the full issue available to our non-paid subscribers because we are doing something we rarely do at Porter & Co.: we’re issuing a short recommendation, which you can read more about below… |

In this issue, we’re issuing a short recommendation… for just the second time in two weeks.

Shorting stocks – which means we are banking on the share price to decline – is risky and it’s expensive to pull off. As we mentioned last week when we recommended shorting shares of aircraft manufacturer Boeing (BA), the best possible outcome is a 100% return if the stock goes to zero. The worst possible outcome, though, is losing your entire investment and more.

Shorting also goes against the longtime odds of the stock market, which historically has been up more than it has been down – on an annual basis since 1926, the overall market has risen nearly 75% of the time.

But there are situations when shorting can make sense. One such time is when there is a high level of certainty that the shares of a particular company are going to decline. In the case of Boeing last week, the company’s reliance on cutting corners has led to disastrous and deadly plane crashes, while its financial mismanagement has created a sky-high pile of $57 billion in debt. As we detailed, it’s almost inevitable that BA shares will drop, possibly to zero, over the next few years.

Another such time is in a bear market, when the profits from short exposure can be considerable. That’s because of what’s known as crisis alpha, or the ability to generate profits when everything else in a portfolio is falling in value. Those profits can then be invested into buying high-quality, capital efficient businesses at deeply discounted prices, setting the stage for massive long-term wealth creation.

In that context, the real value of shorting stocks is as a tool for limiting losses, reducing portfolio volatility, and securing capital during a bear market. And we believe it’s only a matter of time before the supremely elevated valuations in today’s market, combined with a financially tapped-out consumer, give way to a significant bear market.

So today, we’re making another short recommendation.

It comes with a warning that is likely to be ridiculed by Wall Street… similar to, in the past, what I’ve written about the failure of General Electric (GE)… General Motors (GM)… Fannie Mae (FNMA) and Freddie Mac (FMCC)… and, just last week – Boeing.

But like these prior warnings, my analysis leads to one clear conclusion: One of America’s largest, most ubiquitous, and most important financial institutions is in serious trouble.

Tens of millions of Americans place their trust in this bank, so it’s easy to assume that their money and investments are secure. But that’s not the case. If you have an account with this financial institution, you should close it and move your funds elsewhere immediately… and we’re also selling short the shares of this bank.

A Very Big Bank With Very Big Problems

Bank of America (BAC) has long been a pillar of the nation’s financial industry. It’s the second-largest bank in the United States, with $3.3 trillion in assets. Around one in five Americans has an account there, entrusting it with $1.9 trillion in deposits, which is 11% of total U.S. bank deposits. It’s a linchpin of not just the American but the global financial system.

So… you’d hope that it is one of the safest, most closely regulated, and stable financial institutions on Earth.

The thing is… it’s not. In fact, I’m convinced that Bank of America is going to go spectacularly bust. And when it does, it’s going to take down a lot of other banks – and make the bank runs of Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic Bank, and Signature Bank and in the spring of 2023 look like a walk in the park by comparison.

The Problem With Bonds

First, though… a bit of background.

Beginning in 2020, the massive COVID bailouts resulted in $7 trillion in new money being created, which ended up as deposits in the biggest commercial banks. Banks had to invest these funds somewhere, and banking regulation heavily favors buying U.S. Treasury bonds and “Agency” debt, which are both backed by the U.S. Treasury.

The result has been a surge in holdings of these securities by U.S. commercial banks. Since early 2020, U.S. commercial banks increased their holdings by nearly $1.5 trillion, rising as a share of total assets from 19.6% to 23.0% as of the end of Q2 2024. Beyond the significant growth, the increased holdings were in longer-dated maturities, extending portfolio duration, thus exposing banks to heightened interest rate risk.

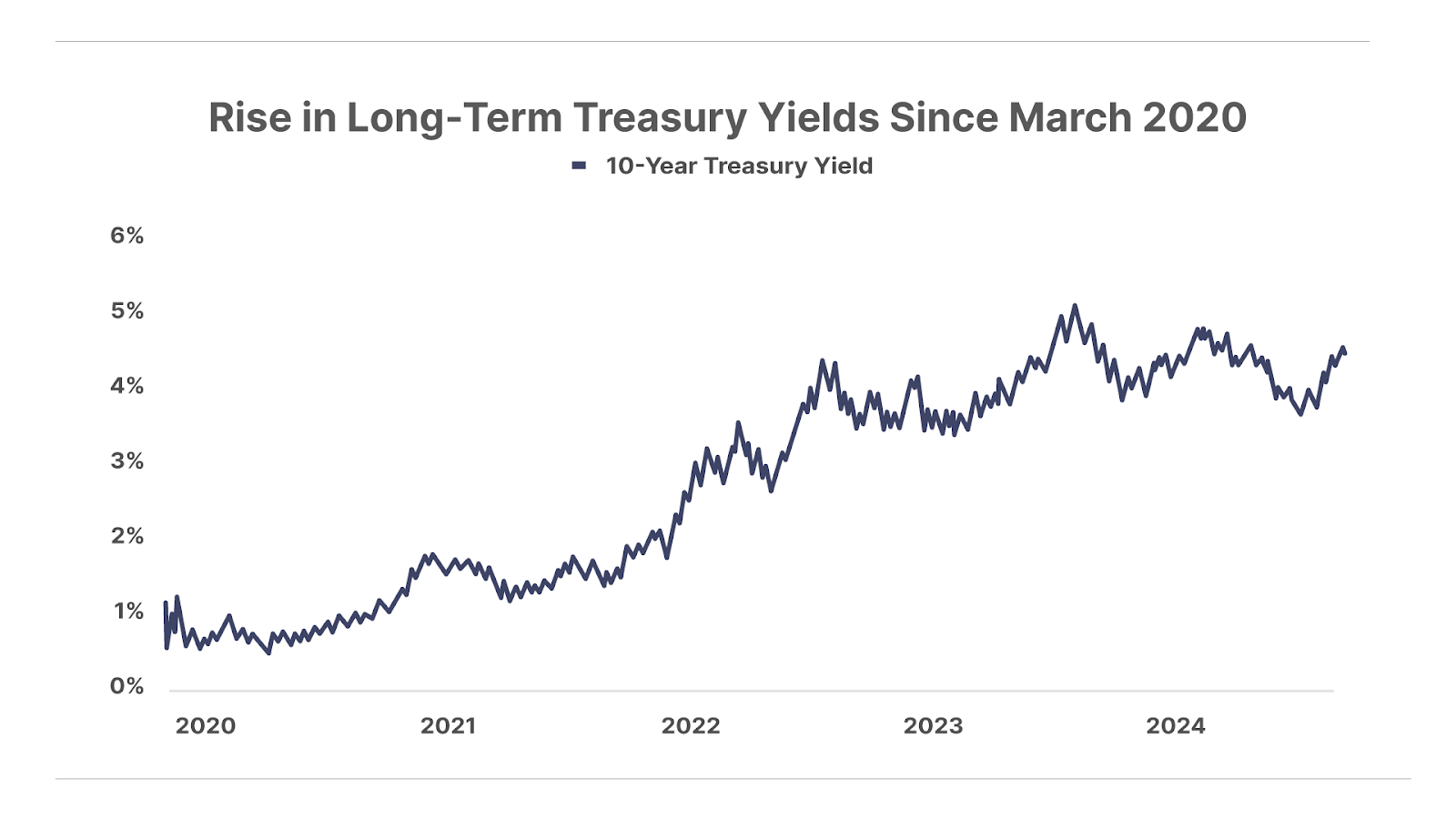

The big problem is that long-term interest rates have risen sharply since then, moving from roughly zero in 2020 to a peak of 5% in early 2024, and roughly 4.4% now.

A brief aside about how bonds work: As the yield of a bond rises, its price declines. In 2020, an investor could have paid $1,000 for a bond that yielded less than 1%. Today, that same investor can buy a bond for $1,000 that yields 4.4%.

What does that mean for all of those 2020 bonds in the market? They’re worth a lot less than $1,000. If you could buy an instrument that yielded nearly five times more, why would you pay much at all for the low-yielding bond? The answer is… you wouldn’t. For example, a 30-year Treasury that was issued in 2020 now trades for as little as $400.

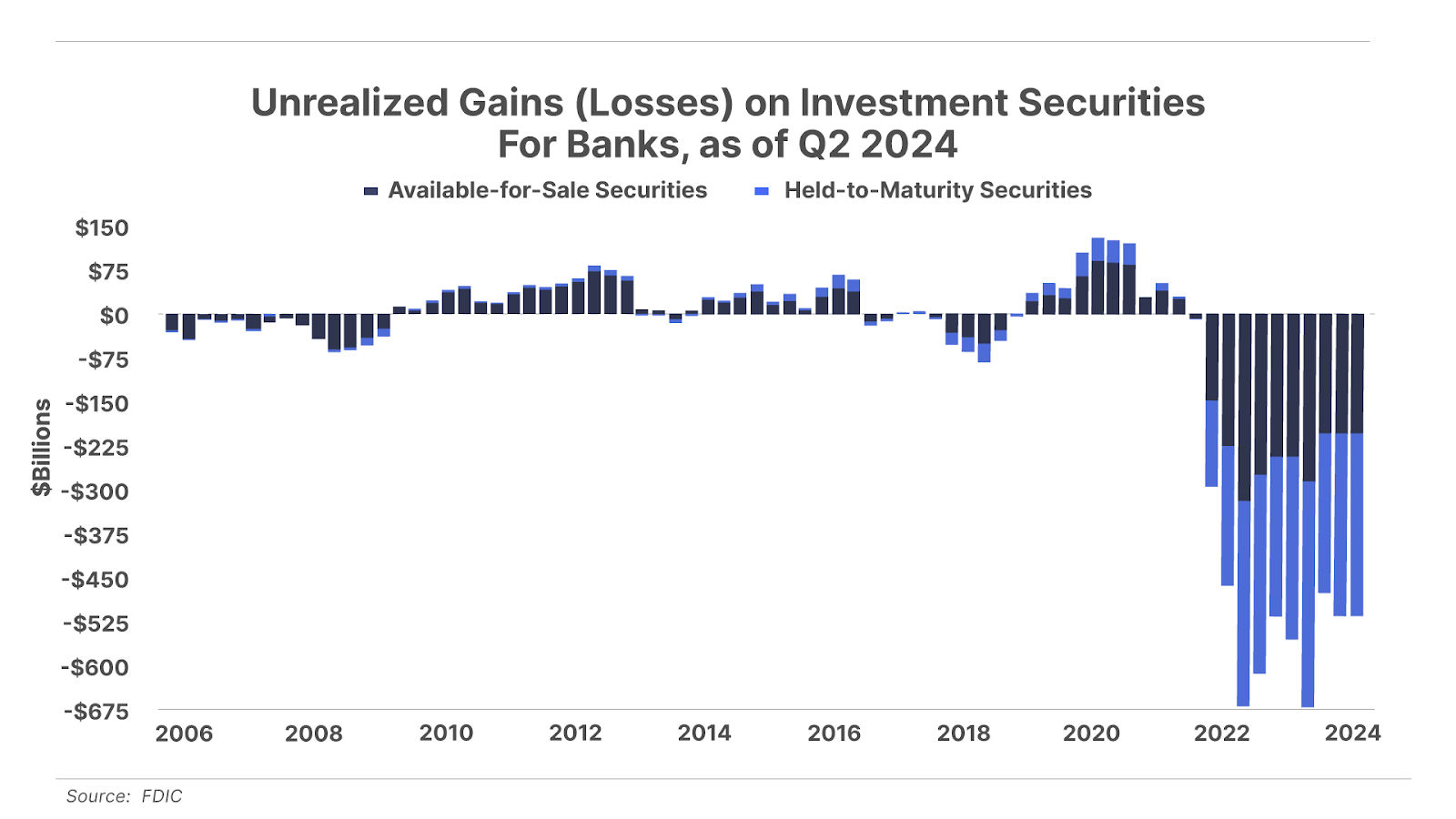

As a result, the banks that loaded up on long-term bonds in 2020 are sitting on enormous losses… As of the end of Q2 2024, U.S. banks were sitting on $513 billion in unrealized losses from their holdings of long-duration Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

That’s nearly 22% of the total equity capital in the U.S. banking system.

And Bank of America has more exposure than almost any other bank.

The Illusion of “Risk-Free” Bonds

Let’s step back for a moment. Why do banks buy bonds in the first place?

Well, they collect deposits and need to do something with the money. They lend it… and they invest it. To encourage banks to own U.S. Treasury bonds, banking regulations consider these assets risk free. Because the assets are considered safe, banks that hold them are allowed to be highly leveraged, following complicated risk-weighted capital regulations put in place as part of the Dodd-Frank reforms, an Obama-era law enacted after the Global Financial Crisis meant to prevent excessive risk taking. The measure was implemented ostensibly to improve the financial system’s accountability and transparency.

These regulations, though, completely ignore market reality – which is that any financial instrument with a fixed coupon (interest payment), like a 20+ year Treasury bond, will have an extremely volatile market price. As real yields fluctuate, investors will adjust what they are willing to pay for that instrument. This can potentially inflict huge losses on the banks, and limit their liquidity during a bank run – because if a bank can only sell a note for (say) $500 that it paid $1,000 for, it has lost 50% of the deposits that investment represents.

In short, by pretending that U.S. Treasury bonds are risk-free when they’re not, the banks’ biggest assets, rather than being a bulwark against market volatility, have actually become the biggest source of volatility.

Risk-weighted capital is a deeply misleading figure. The real metric to look at is how much actual equity capital a bank holds – that’s the figure that tells the investor how prepared the bank is to absorb a shock, regardless of the source.

Bank of America: The Worst Investor in History

Bank of America CEO, Brian Moynihan, proves that even people in the highest positions in banking can make really dumb decisions with other people’s money.

Moynihan made what may well be the single worst investment in the history of capitalism in the summer of 2020 when he bought more than $500 billion worth of “COVID bonds” – long-duration mortgages paying only about 1% a year.

As a result of this huge investment in low-yield, high-duration (15 years+) bonds, Bank of America can’t afford to offer its customers interest on their deposits: Depositors are being paid just 0.01% to 0.04% on checking and savings accounts – making it very vulnerable to a run on the bank if its customers pull their money out to put into another bank offering higher interest rates on their deposits.

And even so, the bank’s yield spread (that is, the difference between what it earns on its money, and what it pays depositors) is still only around 2.2%. So, if the bank offered even 1% on its deposits, its earnings would virtually disappear.

Today, Bank of America has $89 billion in unrealized losses on that bond portfolio. The bank has tangible equity (that is, real equity) of $200 billion. As rates go higher, the losses will grow. The losses on these bonds – in the not-at-all-unlikely event that it would need to sell a very significant portion of them – will bankrupt Bank of America.

These losses, and the inability of Bank of America to pay a competitive interest rate for deposits, will eventually trigger a run on the second-largest bank in America. And while no one is talking about it now, these events can happen in an instant. Once a run starts, a trickle of cash out of Bank of America can quickly escalate into a flood. In the era of smartphones and online banking, a majority of depositors could flee with their money in a matter of hours.

In fact, there isn’t any logical explanation for why such a run hasn’t already occurred… not when depositors can earn 4%-plus in deposit accounts at banks such as SoFi, Discover, and Goldman Sachs – or better yet, 4.50%-plus in short-term U.S. Treasuries.

This is exactly what happened in the spring of 2023 to First Republic Bank, Signature Bank, and Silicon Valley Bank, all of which owned similar bonds on their balance sheets that were very low-yielding and thus couldn’t be sold without huge losses.

Yet… when Bank of America reported third quarter 2024 earnings last month, Moynihan called the results “solid,” noting growth in investment banking, asset management fees, and sales and trading revenue. “I thank our teammates for another good quarter. We continue to drive the company forward in any environment.”

Neither he – nor the 19-page quarterly press release – made any mention of the enormous losses in the bank’s $850 billion bond portfolio.

Follow The Money

When Warren Buffett sells a significant portion of a holding, it’s worth taking note.

And for the past four months, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (BRK) has been selling shares of Bank of America. These details are public: As of October 2024, Berkshire Hathaway had sold 260 million BAC shares at an average price of $41, for proceeds of $10.6 billion. These sales reduce Berkshire’s stake in Bank of America to less than 10% – a level below which Buffett no longer has to immediately report any additional sales. Berkshire Hathaway still owns more than $30 billion worth of shares in the bank.

What nobody has figured out is whether Berkshire is going to dump its entire position. The even bigger secret is why Berkshire has sold almost all of its other bank stocks since early 2020 as well:

- Sold 100% of its 346 million shares in Wells Fargo (WFC)

- Sold 100% of its 150 million shares in U.S. Bancorp (USB)

- Sold 100% of its 60 million shares in JPMorgan Chase (JPM)

- Sold 100% of its 12 million shares in Goldman Sachs (GS)

In regard specifically to Bank of America, Berkshire invested $5 billion in the bank in 2011. This was one of the most famous “Buffett deals.” Berkshire bought preferred stock that paid a 5% dividend and gave Buffett the right (but not the obligation) to buy 700 million common shares at $7.14 each. Berkshire exercised its conversion rights in 2017. And then, in 2018 and 2019, Berkshire continued buying, adding another 300 million shares at prices in the high $20 range, worth approximately $8 billion.

This was a massive move that he is now undoing. Since July 2024, Buffett has been selling as fast as the market will allow.

And he’s not the only investor who sees what’s coming. Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates (the largest hedge fund in the world) has recently dumped more than $100 million of Bank of America and virtually every bank stock in America, including: JPMorgan Chase (JPM), Wells Fargo (WFC), Goldman Sachs (GS), Morgan Stanley (MS), Bank of Hawaii (BOH), PNC Financial (PNC), Citizens Financial (CFG), and Capital One Financial (COF).

The banking sector’s losses on investment securities is only part of the problem. These institutions are also sitting on an estimated $120 billion in losses from commercial real estate (“CRE”) loans. Richard Barkham, chief economist at CBRE – the world’s largest CRE investment firm – estimates these losses would wipe out 100% of the tier-one capital buffer at over 300 U.S. banks.

That’s on top of any expected losses that would normally occur during a credit-cycle downturn. We expect record defaults in the unprecedented $5 trillion of consumer credit spanning auto loans, credit cards, student debt, and personal loans, not to mention nearly $3 trillion in commercial and industrial loans.

How A Run Happens… And What’s Next

In the 12 months after the Fed started raising rates in March 2022, depositors yanked nearly $1 trillion from U.S. banks. Never before in history have we seen deposit flight on this scale.

And though deposits have recovered some of those losses since, here’s the real issue: In today’s world, 100% of bank deposits are only a few taps on a cell phone from heading out the door. Bank of America, due to its massive purchases of low-yielding long-term bonds, currently has an average portfolio yield of only 2.44%. There’s no way that Bank of America can pay anything like short-term Treasury yields in excess of 4.5%.

Thus… it is only a matter of time before depositors take notice. They’re not being paid anything like a fair rate of return. And, Bank of America is, mostly likely, already insolvent. The only thing that’s keeping Bank of America alive is that no one has noticed this situation yet.

That and… the FDIC. Without the protection of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Bank of America would, mostly likely, collapse tomorrow. That’s because it has a huge hole in its balance sheet that the U.S. government is allowing it to fudge.

All those people with accounts at Bank of America might say: I’m not worried because Bank of America is too big to fail. And the FDIC will pay back depositors, right?

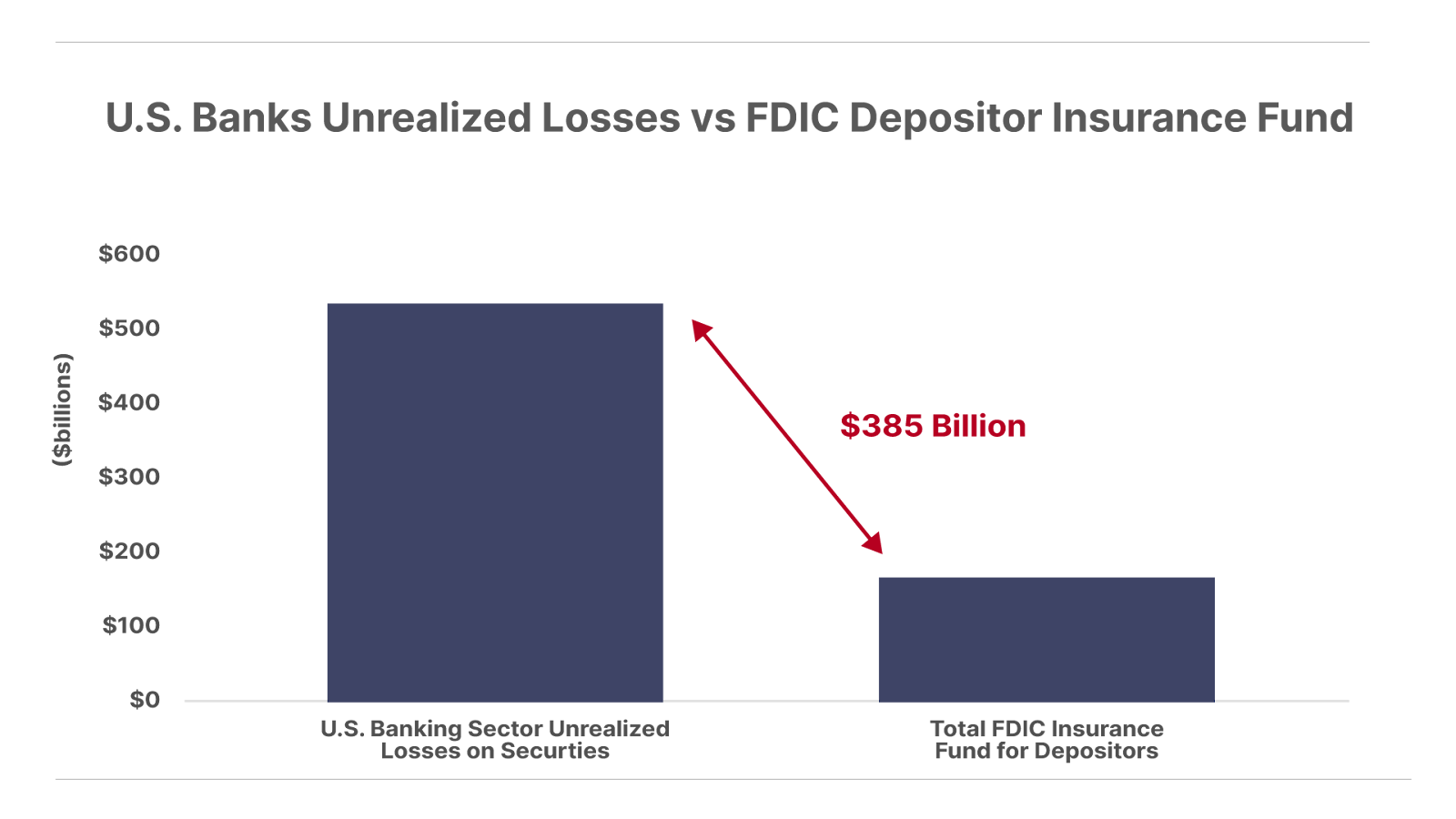

Yes… perhaps. But the FDIC is dramatically underfunded compared to the unrealized losses on U.S. banks’ balance sheets.

So the FDIC will undoubtedly need more money. And the Federal Reserve will always backstop the banks, no matter how poorly run they are… how greedy their managers are… or how absurd their risk-management policies are. And when that happens, who pays the bill?

You do… I do… as more money-printing generates more inflation… continues to run up the federal debt… and, as we’ve written before, slowly erodes the fabric of American society.

When a run happens, it won’t take days or weeks. It will take hours. A run on Bank of America could spark panic in other banks too, of course. The end result will lead to yet another national bailout of the banks.

And that will drive inflation far, far higher. It will also panic the stock market… which now sits at a record high.

Do This Now

First, don’t wait to get your money out of Bank of America. To quote the sinking firm’s CEO, John Tuld, from the famous Wall Street movie Margin Call, “If you’re first out the door, that’s not called panicking.”

Ideally, we recommend holding the bulk of your cash in short-term Treasuries, either directly or via an exchange-traded fund. You might also consider opening a bank account outside the U.S. – which isn’t easy, but well worth the hassle. And be sure to “hedge” your cash with some physical gold and Bitcoin.

Next, the best way to shelter your investable assets from the inevitable bust of Bank of America is to diversify… into the shares of high-quality, capital efficient companies like those we recommend here in The Big Secret on Wall Street.

Finally, those willing to take a little more risk can consider shorting Bank of America shares as well. Like our Boeing short recommendation last week, we believe shorting BAC shares should offer “insurance” to help offset potential losses in the event of a bear market.

But again, as we noted last week, stock prices can and often do diverge from their fundamentals over the short-term. Given the risks involved with short selling, where there is theoretically no limit to how much you can lose, we are recommending a stop loss of $60 per share, or roughly 30% above current levels. This would represent a new all-time high for BAC shares – above its previous pre-Global Financial Crisis peak – and suggest our timing was premature.

We also urge investors to size this position appropriately, in order to withstand the potential for shares to move as much as 30% higher. If that happens, we would recommend exiting the position in order to limit the potential losses.

| Action to Take: Short Bank of America (NYSE: BAC) above $45, with a stop loss at $60 per share |

For readers who aren’t familiar with shorting shares, the process is very similar to buying shares, except the orders are reversed: you sell to open the trade, and then buy to close.

The first step is to ensure you have the trading permissions from your brokerage provider, including the option to make short sales, as well as margin borrowing capabilities. Once you have these trading permissions, most brokerage platforms will have a field where the user will input the ticker symbol of the company, and an option to “sell short” or “sell to open” for initiating the short sale. When the time comes to exit the trade, you will then “buy to cover” or “buy to close” the short position.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

Mailbag

In The Big Secret on Wall Street mailbag, Porter answers letters from readers. He cannot offer individual investment advice, but can respond to general questions.

Please email us at [email protected] to have your questions answered. We’d love to hear from you!

Today’s first letter comes from T.O., who writes:

You reference Q2 earnings for ARM Holdings in the year 2025. Is this a typo or mistake? You also reference a 10% trailing stop loss, but show purchase price at $138 with current market at $134. This is not 10%. I am confused by this communication as there are too many inaccuracies in it. Can you please confirm the legitimacy of communication with more realistic and accurate data?

Porter’s comment: Sure – although I will note that there are no inaccuracies in our latest update on ARM Holdings (Nasdaq: ARM). ARM, like many companies, reports earnings based on a fiscal calendar that’s different from the calendar quarter. As we wrote in our sell alert on November 19, ARM’s fiscal Q2 2025 quarter references the three-month period ending on September 30:

ARM posted better-than-expected earnings and revenue for its fiscal Q2 2025 reporting period (the quarter ending September 30) after the close of trading on November 6…

As for the question on the calculation of the stop loss, note that we use a “trailing” stop loss, which “trails” the share price higher over time. As a simplified example, if we recommend buying a stock at $100 with a 10% trailing stop, the initial stop loss is 10% below the entry price, or at $90 per share. If the stock rises to $110, the stop loss moves higher as well, which in this example would move to 10% below $110, or $99 per share.

In this way, a trailing stop is designed to lock in gains and limit losses relative to a fixed stop loss. Fortunately, the TradeStops service takes care of all the math for us, and that’s one of the many reasons why we recommend using this service. And in our latest update on Arm published November 19, we have provided the latest trailing stops for all of our open positions in the Parallel Processing Revolution stock basket, which if followed, should allow for healthy gains across the board even if these stop losses get triggered.

Today’s second letter comes from A.R., who writes:

The P&C Insurance Valuation Report is interesting, but prompts me the following question: What is more important, discount or return on equity (“ROE”) and up to what point? The question is because the discounted ones seem to have low ROE, and Progressive (PGR) has high ROE…

My second question: I have read many times, if I understood correctly, that the float does not belong to the company, but the revenue on it does belong to the company. Could you elaborate on this? For example, if a severe catastrophe happens, the claims are higher than the reserves and the float, what happens to the P&C insurance company?

Thanks in advance.

Porter’s comment: Thanks for your question.

On the first point, you are correct in your assessment that higher-quality insurance companies (measured by ROE) typically command higher valuations than their lower-quality counterparts. As for which is more important: buying a high-quality company at a valuation premium, or a lower-quality business that trades cheaper, we refer to Warren Buffett’s advice:

It is far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.

Yes, there is a limit to what constitutes a “fair” price. This is unique for each company, but in general, higher returns and faster growth rates can justify higher valuations. In the case of a company like Progressive, which is among the highest-quality insurers in the market based on its returns and growth rate, we can justify paying a higher price and still expect to generate market-beating returns, as we have with that recommendation to date. Even today, after a nearly triple-digit return, the shares remain attractively valued at less than 20x earnings, or a roughly 25% discount to the S&P 500. In this case, investors get the chance to buy a high-quality company at what we would argue is a more than fair price.

In regards to your second question, you are correct that the float generated by insurance companies is contributed by policyholders paying their premiums. As such, this is money not technically “owned” by the insurance company, but rather owed to its policyholders. That’s why it doesn’t show up on the asset side of the balance sheet.

If an insurance company ends up paying out more in claims versus the float it collects in premiums, instead of earning a profit on its underwriting, it generates a loss – which eats into the company’s own capital, instead of building it. While this can happen in any given single year from an unexpectedly large catastrophe, over the long run, high-quality insurance companies will tend to pay out less in claims versus what they generate in premiums. That’s why it’s critical to only buy well-run insurance companies that have a long track record of excellent underwriting discipline, so that they end up generating a profit on their insurance underwriting, and also earn the positive returns available from investing their float over time.

The key metric for measuring the success of an insurance company’s underwriting ability is through the combined ratio, which tells you how much of the premiums collected they retain as earnings over time. For the insurance companies we’ve recommended to date, you’ll note that they tend to generate combined ratios consistently below 90, meaning they retain more than 10 cents of every dollar in premiums collected as earnings.

P.S. One of the safe havens in a bank collapse is also the best way to preserve value over time… and that’s gold.

In the days after the U.S. presidential election, the price of gold fell 8%, as investors went “risk on.”

But subsequently – as investors realized that geopolitical dangers, the ongoing debasement of the U.S. dollar, inflation, and the escalating federal debt didn’t magically evaporate overnight – the price of gold has resumed its upward trend.

And that’s not going to stop.

Not long ago, Porter sat down with gold expert Marin Katusa to discuss the best ways to invest in gold (hint: It’s not buying it at Costco…). It involves investing in a kind of asset that usually tracks the price of gold – but during the current gold rally, has seriously underperformed. That’s going to end soon… watch Porter’s conversation to find out why… and how to best capitalize on this gap – and the pending mean reversion.