Issue #31, Volume #2

What A Real Bear Market Looks Like

This is Porter’s Daily Journal, a free e-letter from Porter & Co. that provides unfiltered insights on markets, the economy, and life to help readers become better investors. It includes weekday editions and two weekend editions… and is free to all subscribers.

| The bond market collapsed in the late 1970s… Marty Fridson reflects on 21% interest rates and a 27% drop in bond prices… There are always gems to be found when there is lots of distress… The latest episode of the Black Label Podcast drops today… |

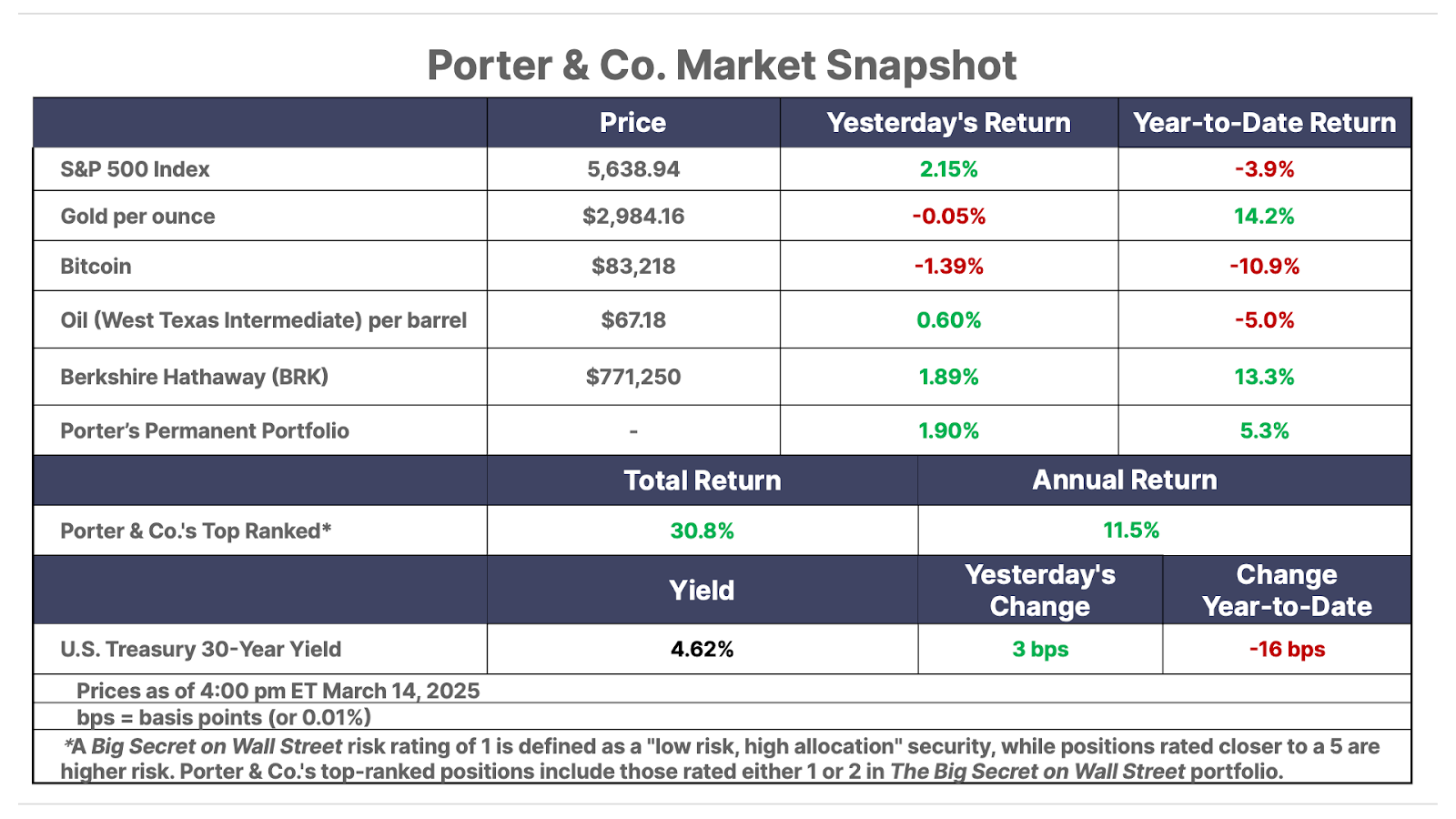

U.S. stocks last week were down 10% from recent highs – which is defined as a correction – erasing around $5 trillion in market value. That’s not pocket change…

And that’s only half way to a bear market (down 20%)… and even that is just for starters.

So to remind us what a real bear market feels like… we asked Marty Fridson, the lead analyst for Porter & Co.’s Distressed Investing, to help us out. Marty is a pioneer of the entire asset class of bonds. Marty has seen it all… Investor’s Digest called him “the most well-known figure in the high-yield world.” Over a 25-year span with Wall Street firms including Salomon Brothers, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch, he became known for his innovative work in credit analysis and investment strategy. Marty joined Porter & Co. in March 2023. Since then he’s made 17 distressed-bond recommendations, which are up 16%… and eight distressed equity recommendations that are up an average of 31%.

Below, Marty describes the brutal bond bear market of 1978-1982, when super-high interest rates caused yields to soar and prices to plummet.

Here’s Marty…

Unsettling as the recent share price decline is – particularly after two straight years of 20%+ returns – I’m here to tell you that a real downturn in the financial markets feels a whole lot worse.

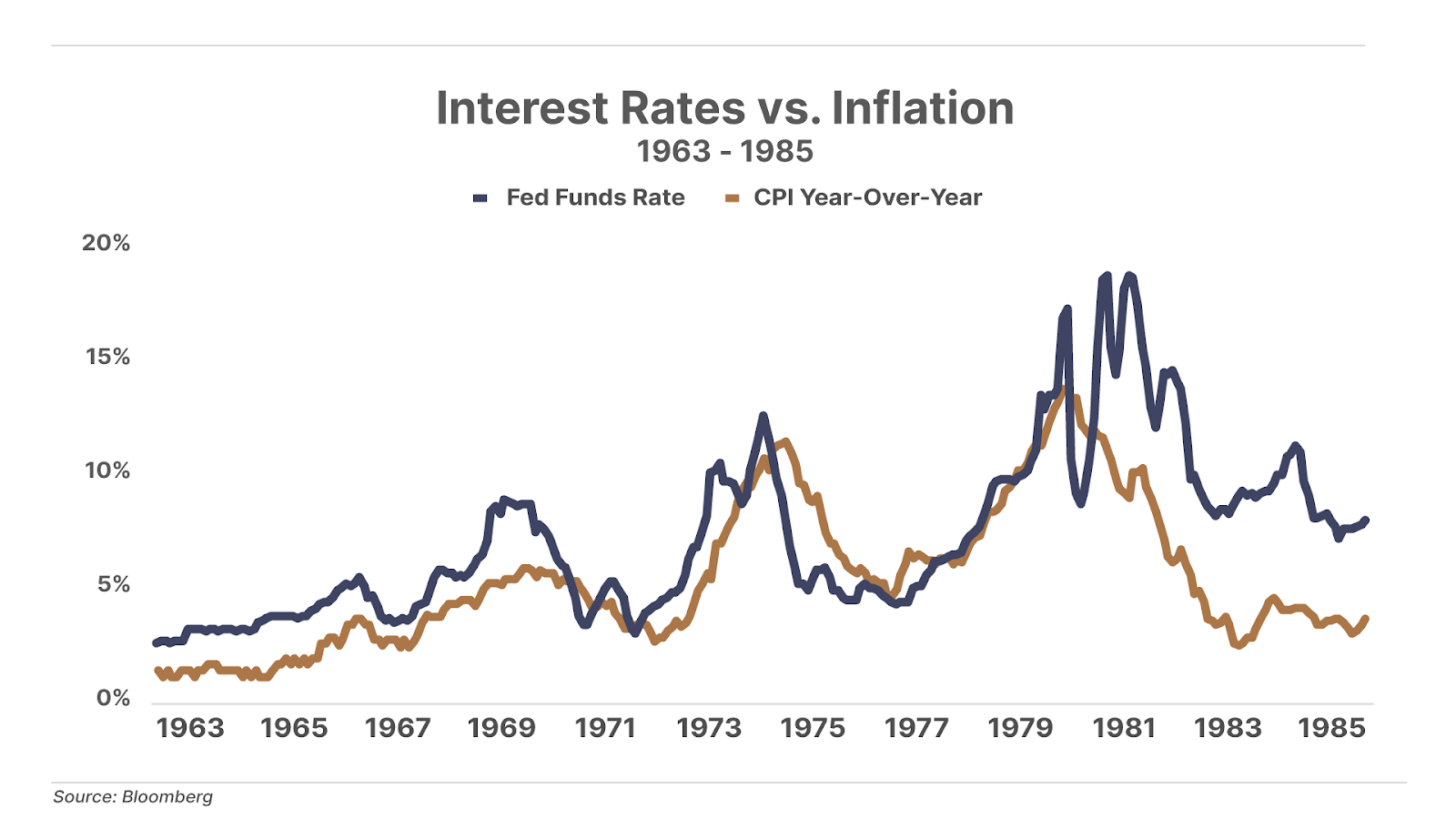

The late 1970s/early 1980s was a bond market apocalypse. Inflation is the mortal enemy of fixed-income investors, and the U.S. economy suffered serious inflation during that period. The seeds of rising prices were sown under President Lyndon Johnson’s 1960s “guns and butter” policy – the double whammy of paying for the Vietnam War, and funding massive social programs. The huge infusion into the money supply sent the consumer price index (“CPI”) soaring to a year-over-year peak of 14.8% in March 1980 (today, it’s just under 3%).

Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker made it his mission to club inflation into submission by reining in the expansion of the money supply. Through his efforts, the Fed funds rate – the key rate for managing U.S. monetary policy – which stood at 6.53% at the beginning of 1978, skyrocketed to 21.09% on July 1, 1981. That sent the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury yield rising from 7.78% to 14.04% over the same three-plus-year period.

I experienced firsthand the impact of interest rates shooting up so dramatically, so quickly. In 1980, my wife and I pooled our entire life savings to make a down payment on a one-bedroom apartment in New York City. A bank loan officer jumped through hoops to enable us to get a loan to cover the balance. The loan came with an option: We could either take the then-prevailing 14.5% rate, or accept whatever the rate would be at closing, three months later.

To help us decide, I checked in with a Wall Street chief economist friend. He confidently assured me – presumably thinking that rates had peaked – that the worst was over, and that by the time we completed the purchase, rates would be down considerably. Luckily, I ignored him, and went with my gut, locking in the loan at 14.5% – which was better than the 16% the bank was charging when our loan closed.

The unprecedented upsurge in interest rates during that period had an even greater impact on my professional life. As the Wall Street Journal frequently reminds us, when bond yields rise, bond prices fall. And how they fell! From the end of 1977 to early 1981, the Merrill Lynch U.S. Corporate Index, consisting of investment-grade issues rated from AAA to BBB, plummeted by 27%.

That kind of collapse in bond prices wasn’t supposed to happen. Bonds were traditionally the ballast of an investment portfolio, holding steady while volatile stocks experienced bigger price swings but ultimately delivered higher long-run returns. Asked at the time if he would buy long-term bonds, the CEO of one Wall Street firm replied, “I may be stupid, but I’m not crazy.”

During this financial bloodbath I personified the typical senior trader slight about youth in the market.… I was indeed “the 26-year-old who’s never seen a bear market.” For the first couple of years after entering the business in 1976 as a trader of electric utility bonds, I was consistently profitable. There was a sizable bid/ask spread on the small lots that I dealt in, and the market fluctuations were modest. As long as I kept close tabs on price quotations, I dependably made money.

But once Fed Chair Volcker put the squeeze on – boosting interest rates – my cozy little niche was upended. As the prices relentlessly marched lower, the bonds that I took into inventory quickly dropped below the levels where I bought them.

In an effort to capitalize on declining bond prices, I very cautiously put on some short positions – which go up in value when the market drops. But shorts are a risky undertaking in the corporate bond market. Not only do you face the risk of loss from a temporary upturn in prices – but also, while you’re short you have to pay the interest that’s accruing on the shorted bond. And because corporate bonds aren’t as liquid as stocks, there’s a danger that you won’t be able to cover the short from other dealers’ offerings. If that happens – and at some point it will – you have to deliver the shorted bond by finding a holder who’s willing to sell… likely only at an exorbitant price divorced from market forces.

All in all, trading corporate bonds was a disastrous experience in the late 1970s. I was tying up a considerable amount of my firm’s capital without being able to generate a return on it.

I was not alone in this predicament. The dirty little secret of Wall Street’s corporate bond trading business was that profitability depended heavily on positive carry – that is, a positive spread between bond yields and the cost of financing bond inventories. Before the bond market collapse, traders earned profits by getting loans at low, short-term interest rates, while collecting the higher-rate interest payments on the bonds for as long as they owned them. That meant that even if they sold a bond at the same price that they paid, they still made money on the deal. But with short-term rates at sky-high levels, the positive-carry profit engine disappeared.

Major firms like Goldman Sachs and Salomon Brothers were able to keep their corporate bond desks going despite the profit drought. They had sufficient capital to wait it out, and were earning income from other lines of business. But my firm and I weren’t that fortunate. At the time, in 1979, I was part of an independent group that had seceded from our original firm when PaineWebber acquired it. We became the corporate bond department of Scandinavian Securities Corporation, a small investment bank owned by a larger Swedish bank that was going after lucrative opportunities in underwriting new issues in the U.S. market. (I started spelling my name Fridsǿn the better to fit in.)

But that’s not what happened – it wasn’t easy to break into U.S. underwriting, and the Europeans weren’t prepared for the trading losses that engulfed us. And at corporate headquarters in Stockholm, the mindset wasn’t to stick with the American initiative no matter how long it took, or how much capital had to be injected until market conditions improved.

Scandinavian Securities Corporation wasn’t long for the world. The collapse of the bond market killed it, along with its bond department. Luckily for me, a former senior colleague who had stayed with PaineWebber thought I had the makings of a good credit analyst, and took me back. Landing a credit-analyst job at PaineWebber in 1980 worked out extremely well for me, as the high-yield market was beginning to take off around that time. From a career standpoint, it was a case of no Paine, no gain and resulted in a very happy ending. I stayed there two years before moving on to Salomon Brothers, and eventually became head of corporate bond research at Morgan Stanley.

Investors who bought bonds at the lows of the early 1980s also made out exquisitely. In the four years beginning July 1, 1982, the price of the previously mentioned corporate bond index (which had fallen 27% at the low point the first quarter of 1980), jumped 51%. Again, that’s the sort of volatility that you’re not supposed to see in high-quality bonds, but this time around it was upside volatility… so everyone involved was happy about it.

So that’s what an honest-to-badness bear market looks like. It’s pretty brutal on the nerves, the pocketbook, and the career. But getting buried by the market has its benefits. Way below ground level lie hidden treasures in the form of securities that can be had for far less than their intrinsic value. And those are the sorts of treasures we find in Distressed Investing, particularly so when we begin to see more distress in the market.

So far the level of correction is nowhere near what the bond market experienced in the late 1970s. But if this 10% decline in the S&P 500 turns into a 20% or 30% downturn, we can see some real bargains arise.

Last week, Porter released a video about how buying distressed bonds is providing him with a Second Life in investing. In his presentation, he talks about how bonds are the investment world’s best-kept secret. They offer a high level of security, superb returns, and significantly less volatility than stocks. You can watch it right here.

Important Note… Marty Joins Porter And Aaron On The Podcast

Marty is Porter and Aaron’s guest on this month’s Black Label Podcast… Marty discusses risk and how to manage it, he explores how tariffs could play out for corporate bonds, and he and Porter share their thoughts on why bonds are better than stocks… Watch this latest episode now, or listen on your favorite podcast platform.

Three Things To Know Before We Go…

1. Fed is unlikely to cut rates. Markets overwhelmingly expect the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates steady on Wednesday. Heading into 2025, investors were pricing in just one rate cut from the Fed. However, after weaker-than-expected consumer price index (“CPI”) and producer price index (“PPI”) reports in February along with deteriorating consumer sentiment, expectations have shifted to three rate cuts this year, which would boost a slumping economy. But the Fed’s preferred measure – core personal consumption expenditures (“PCE”) – suggests inflation is not going away. Airfare, the key driver behind the CPI decline, does not significantly impact core PCE, while categories that do – such as healthcare and financial services – rose sharply in February.

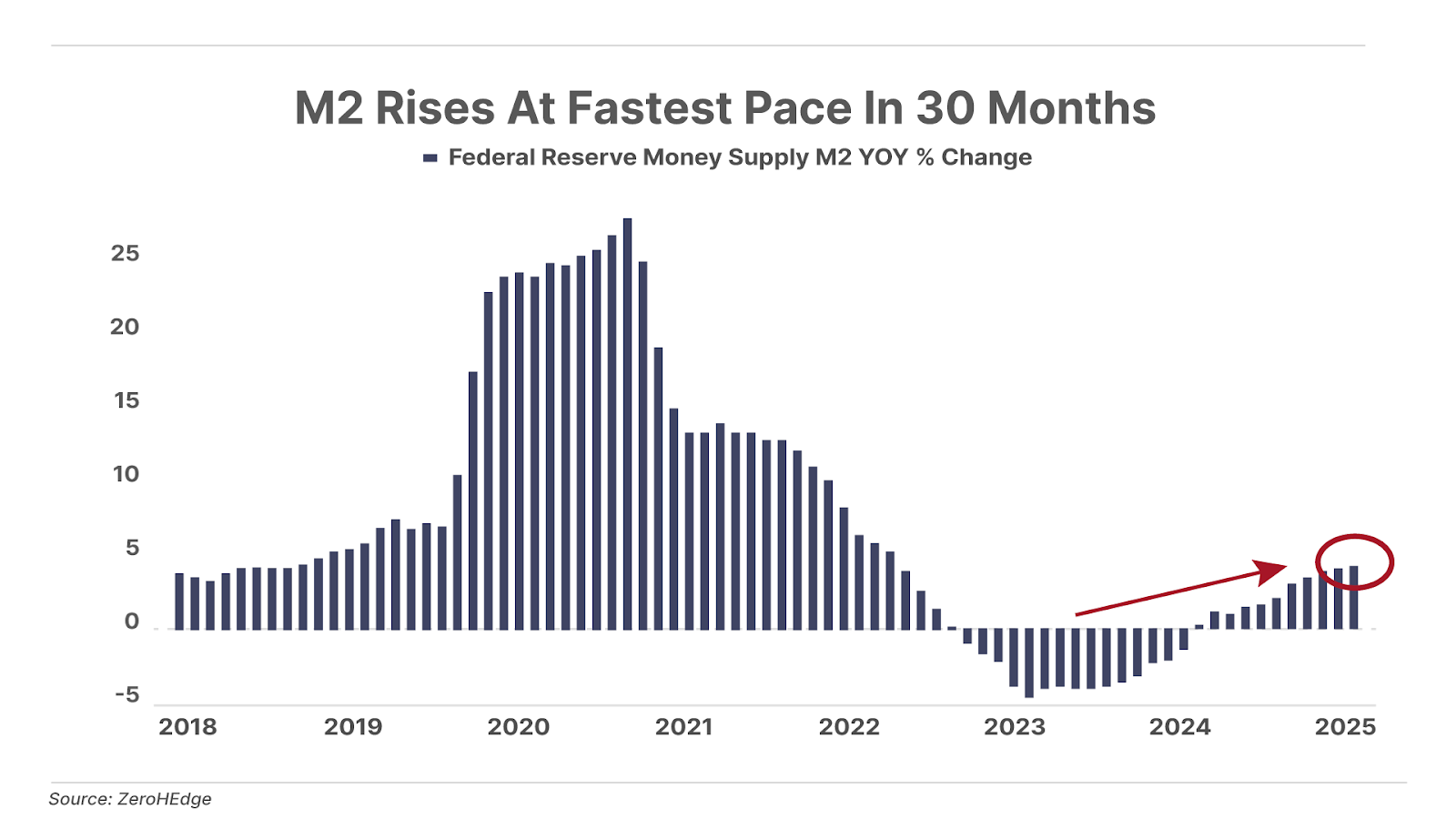

2. Growth in U.S. money supply is accelerating. The latest government data show that M2 – a measure of broad money supply that includes cash, checking and savings accounts, and money market deposits – continues to rise. M2 grew 3.9% year over year (“YOY”) in January, its fastest pace in 30 months. M2 has now expanded for 11 consecutive months, after briefly contracting for the first time in decades in 2022 and 2023. More money sloshing around the economy could ultimately drive both consumer and asset prices higher.

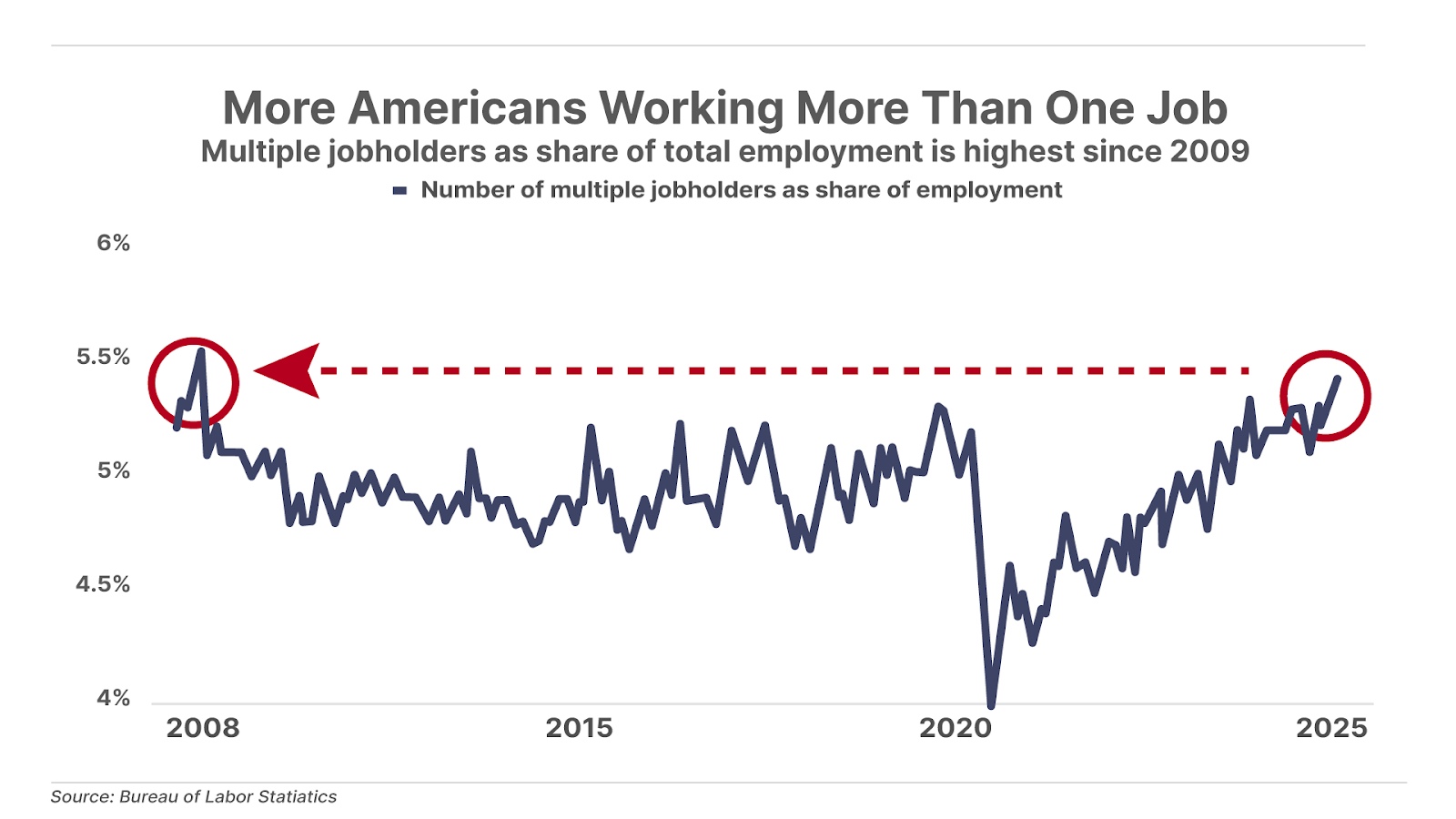

3. How Americans are coping with uncertainty: Working harder. The number of Americans holding more than one job hit an all-time high in February, of 8.86 million people – which is 5.4% of total employment, the highest share in 16 years. Meanwhile, the number of Americans holding a primary full-time as well as a secondary part-time job increased by 395,000 in February – to a record 5.37 million people… which is 3.3% of total employment, the highest proportion since 1999. What’s going on? Plummeting consumer sentiment, inflation concerns, tariffs, an increasing likelihood of recession, market volatility, political uncertainty… faced with a cloudy future, and rising costs, Americans are working more, and harder.

And one more thing… Poll Results: Where Will HOV Be In Five Years?

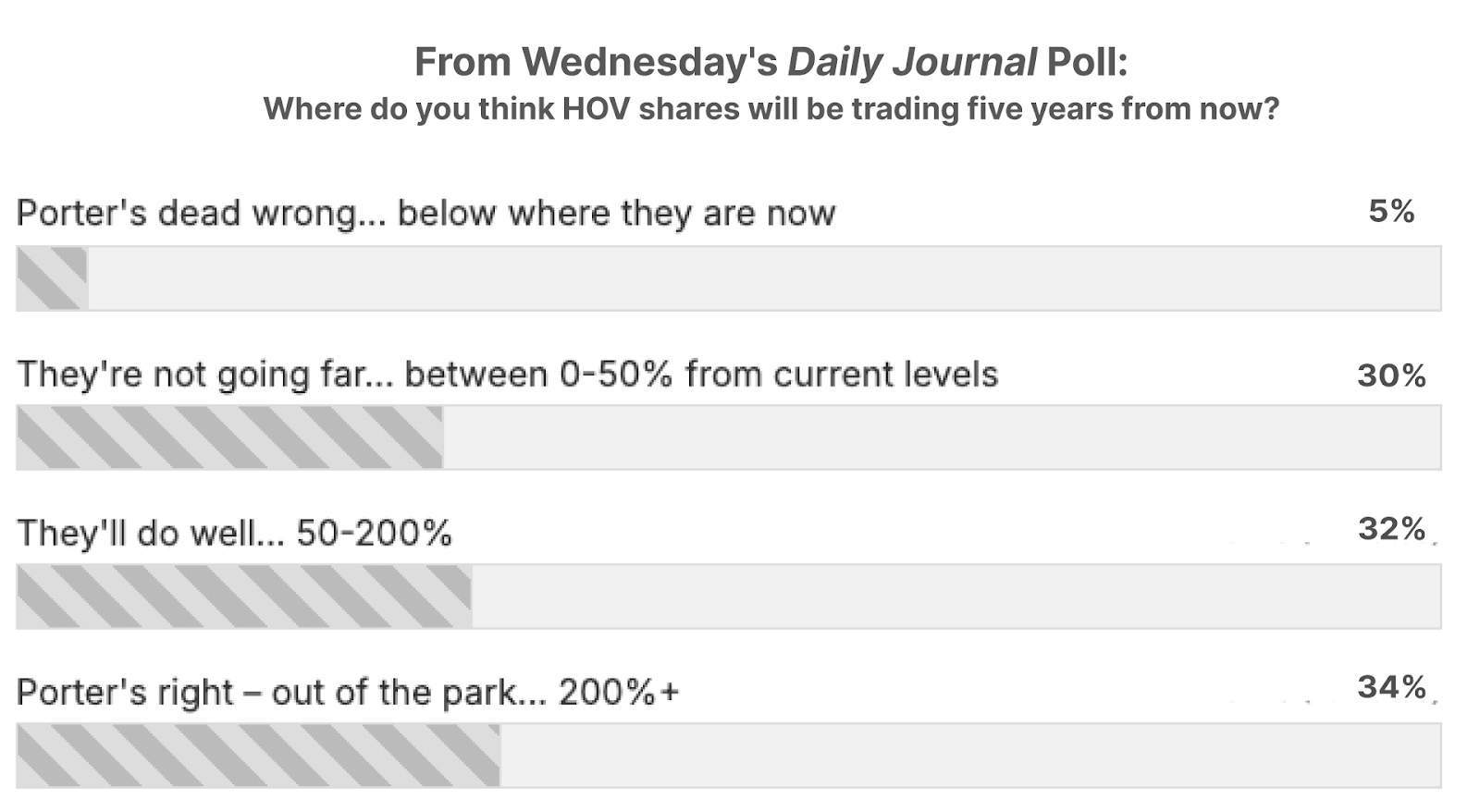

Last Wednesday, Porter shared with readers his analysis of U.S. homebuilder Hovnanian Enterprises (HOV), a company he’s revisiting after regrettably selling shares too soon in 2002, concluding: “Over the next seven years, the results for investors in Hovnanian today will be stupendous – annualized returns in excess of 30%”

We asked Journal readers: “Where do you think HOV shares will be trading five years from now?” Survey takers overwhelmingly agree with Porter on the future of HOV shares, with 34% selecting the option “Porter’s right… out of the park… 200%+,” 32% saying “They’ll do well… 50% to 100%,” with 30% less enthusiastic: “They’re not going far… 0% to 50%.” Just 5% of survey takers selected “Porter’s dead wrong… below where they are now.”

Chinese Issue New Financial Threat to America

Presented by Jim Rickards

The global economic war has arrived.

This announcement from China means they are set to implement massive tariffs on America any day now.

Are you going to learn how to leverage this global trade war to potentially generate returns 1,000% or more in a matter of months as this plays out?

Or are you going to sit on the sideline and become one of the victims in this new economic war?

Click here and I’ll show you everything you need to do.

Coming Up This Week…

Housing and manufacturing data suggest weaker growth. As we reported last week, inflation continues to climb (though slowly) and consumers are nervous. Data out this week will likely reflect those fears. On Tuesday, we’ll see the official release of February’s housing starts data, which tracks the number of new residential builds in the U.S. In January they were down 9.8%, and 0.7% from last January. On Thursday, we’ll also get existing home sales for February – which is expected to show subdued growth of 3% or less, below the historical average.

And please let us know what you think by dropping us an email: [email protected]

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, MD

P.S. Wanted… Porter & Co. Seeks Time-Tested Trader

Do you know anyone who is a battle-tested trader with years of street cred, deep market insight, and the scars and medals to prove it?… Porter & Co. is looking for such a person to lead our premium trading research service, to deliver high-impact ideas to our subscribers. See here for more details… and even if this isn’t you, please note that we offer a generous finder’s fee if you refer us to the right candidate.

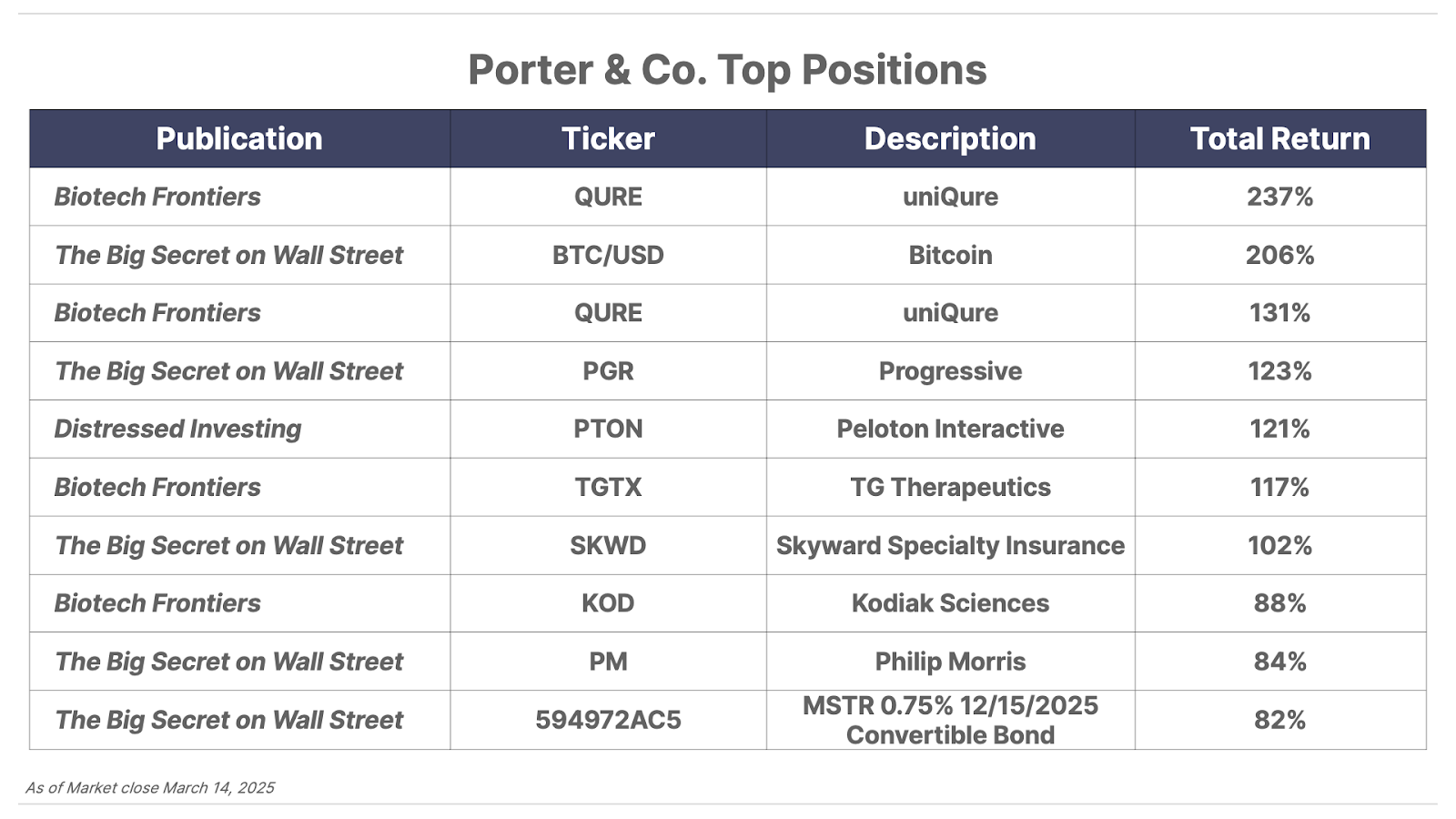

Please note: The investments in our “Porter & Co. Top Positions” should not be considered current recommendations. These positions are the best performers across our publications – and the securities listed may (or may not) be above the current buy-up-to price. To learn more, visit the current portfolio page of the relevant service, here. To gain access or to learn more about our current portfolios, call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447.