Issue #16, Volume #1

And It Continues Today in the U.S. – and Ordinary Investors Pay the Price

Three Things You Need To Know Now:

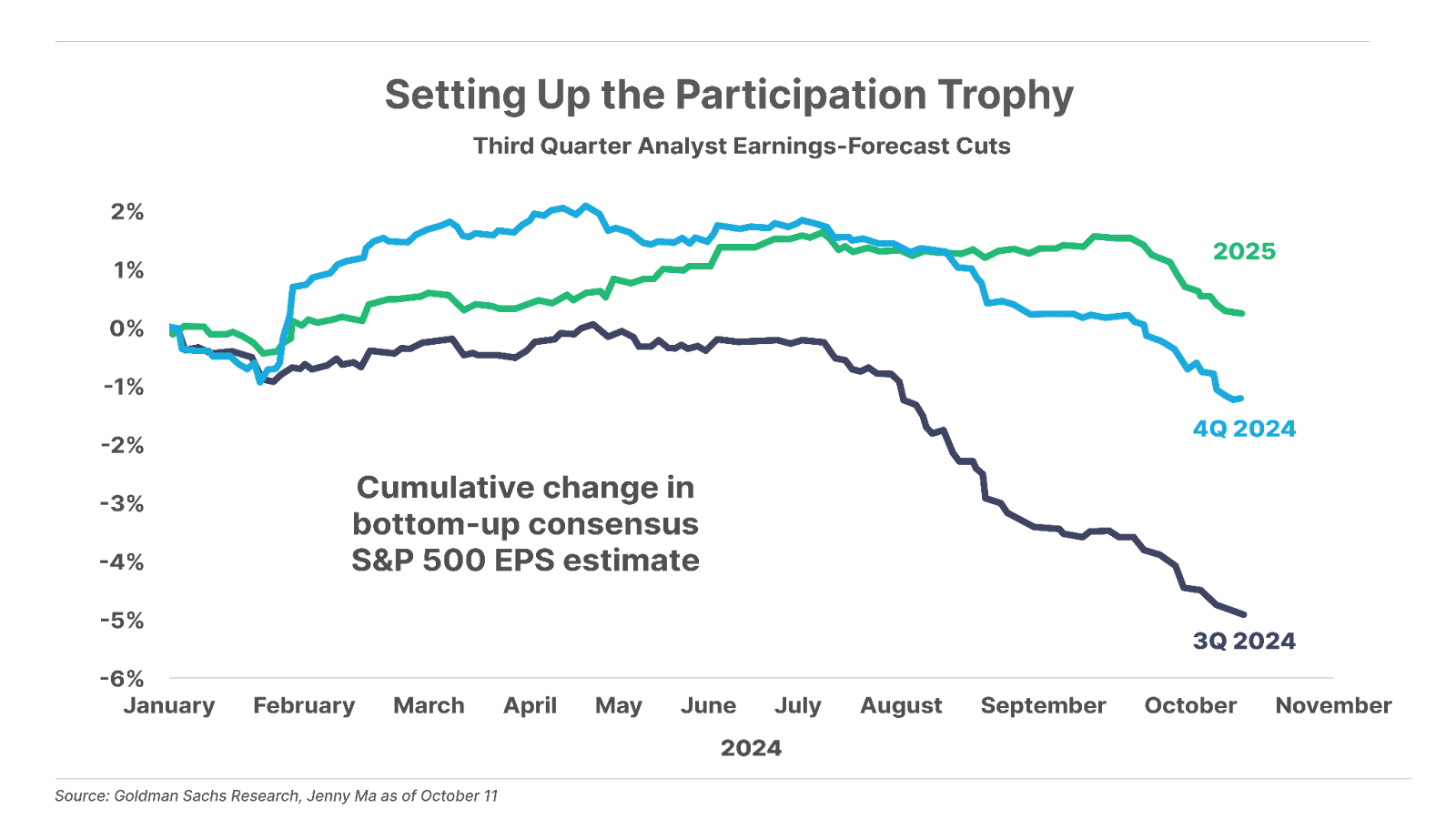

1. Wall Street lowers the bar ahead of earnings season. U.S. corporations kicked off the release of their Q3 earnings reports last week, starting with the big banks, which largely exceeded expectations. We expect more of the same, with a flurry of “better than expected” earnings headlines flashing across CNBC in the coming weeks. But one thing the talking heads likely won’t mention is how these earnings “beats” have been manufactured by the analyst community, which has set an unusually low bar. Over the last three months, Wall Street analysts have slashed their Q3 earnings estimates for S&P 500 companies by roughly 5%. Meanwhile, they’ve also significantly reduced their estimates for Q4 2024 and the full year 2025. Lowered expectations will help corporate America earn the participation trophy-equivalent of an “earnings beat” headline. But, ultimately, earnings will need to be higher – and not just make it over the finish line in seventh place – to justify higher stock prices. And with around 10% of S&P 500 companies reporting earnings this week… look out below if earnings don’t hit these already-reduced expectations.

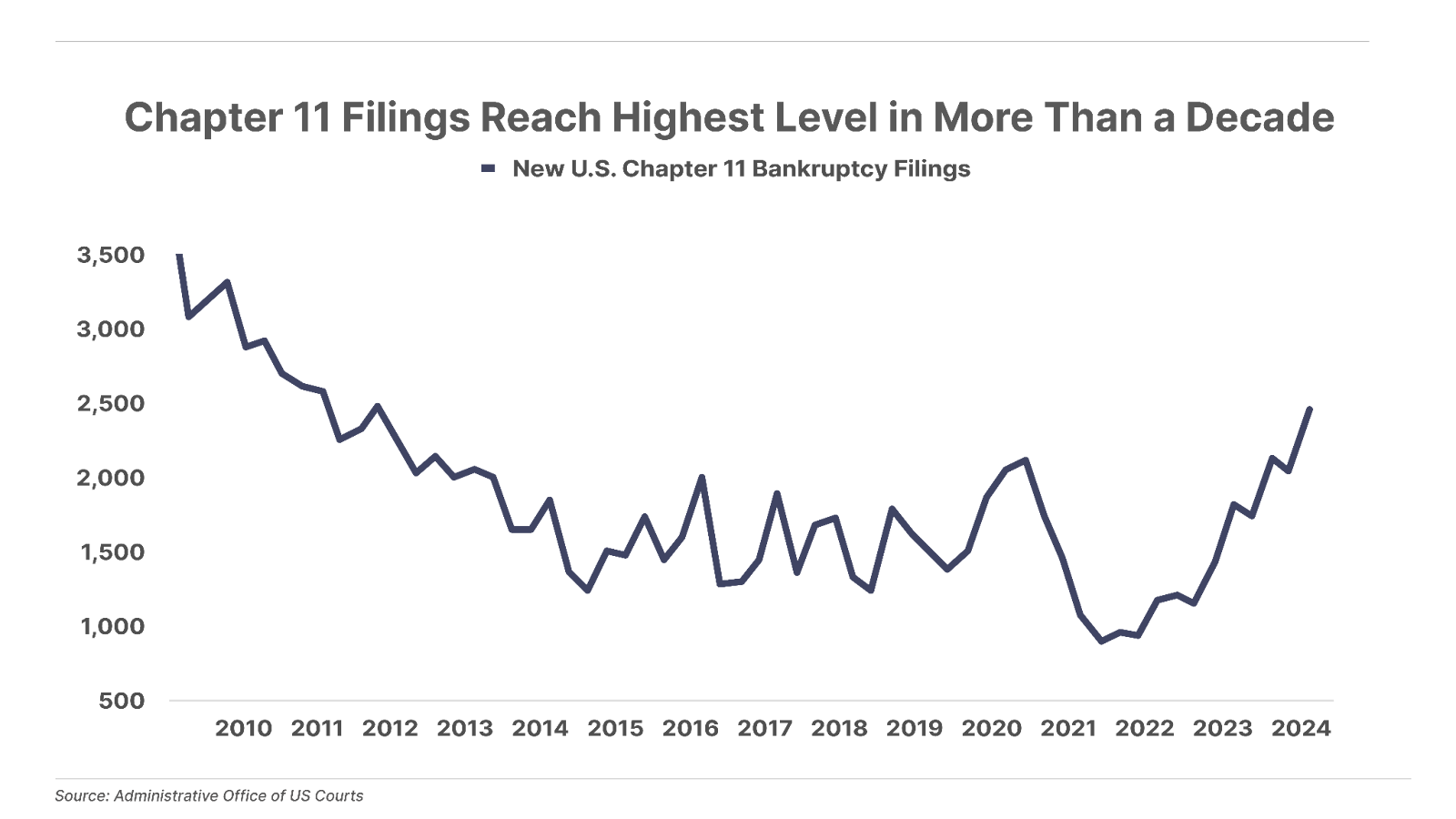

2. A bull market in bankruptcies. Q2 data on Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings shows 2,462 defaults among U.S. corporations, which is the highest level since 2012. The default rate began moving steadily higher following the start of the Federal Reserve’s rate-hiking campaign in Q1 2022. Monetary policy acts with a lag, and U.S. corporations are now feeling the full brunt of higher borrowing costs. Likewise, it will likely take many months, and a series of additional rate cuts, before the Fed’s shift to an easier monetary policy offers any relief. While the stock market seems unconcerned for now, surging default rates typically occur closer to the end of a bull market rather than the beginning.

3. Tesla shares plunge following last week’s disastrous robotaxi unveiling. On Thursday, October 10, Tesla (TSLA) CEO Elon Musk officially introduced the company’s long-awaited “self-driving” robotaxis – named the Cybercab and Robovan – designed without steering wheels or foot pedals.

As is usually the case with Tesla events, this one was heavy on promises, and remarkably light on details and hard deadlines. For example, Musk said the company would begin producing these vehicles “before 2027” (given that since 2017, he’s been promising that full self-driving vehicles were coming “next year,” we aren’t holding our breath), that they will ultimately cost “below $30,000” (the same was said of the Model 3, which still starts above $40,000 despite price cuts), and that they will use “inductive charging” to refuel without a charging cord (which does not yet exist in a commercially viable form). What’s more, Musk provided no explanation of how Tesla was planning to navigate the many technical and regulatory hurdles required to bring these vehicles to market. And unfortunately for Tesla shareholders, Wall Street was not impressed. Shares plunged nearly 9% on Friday. While we commend Musk for his pro-free-speech activism since taking over social media platform X (formerly Twitter), we continue to recommend most investors stay far away from Tesla shares.

Signs of a top…

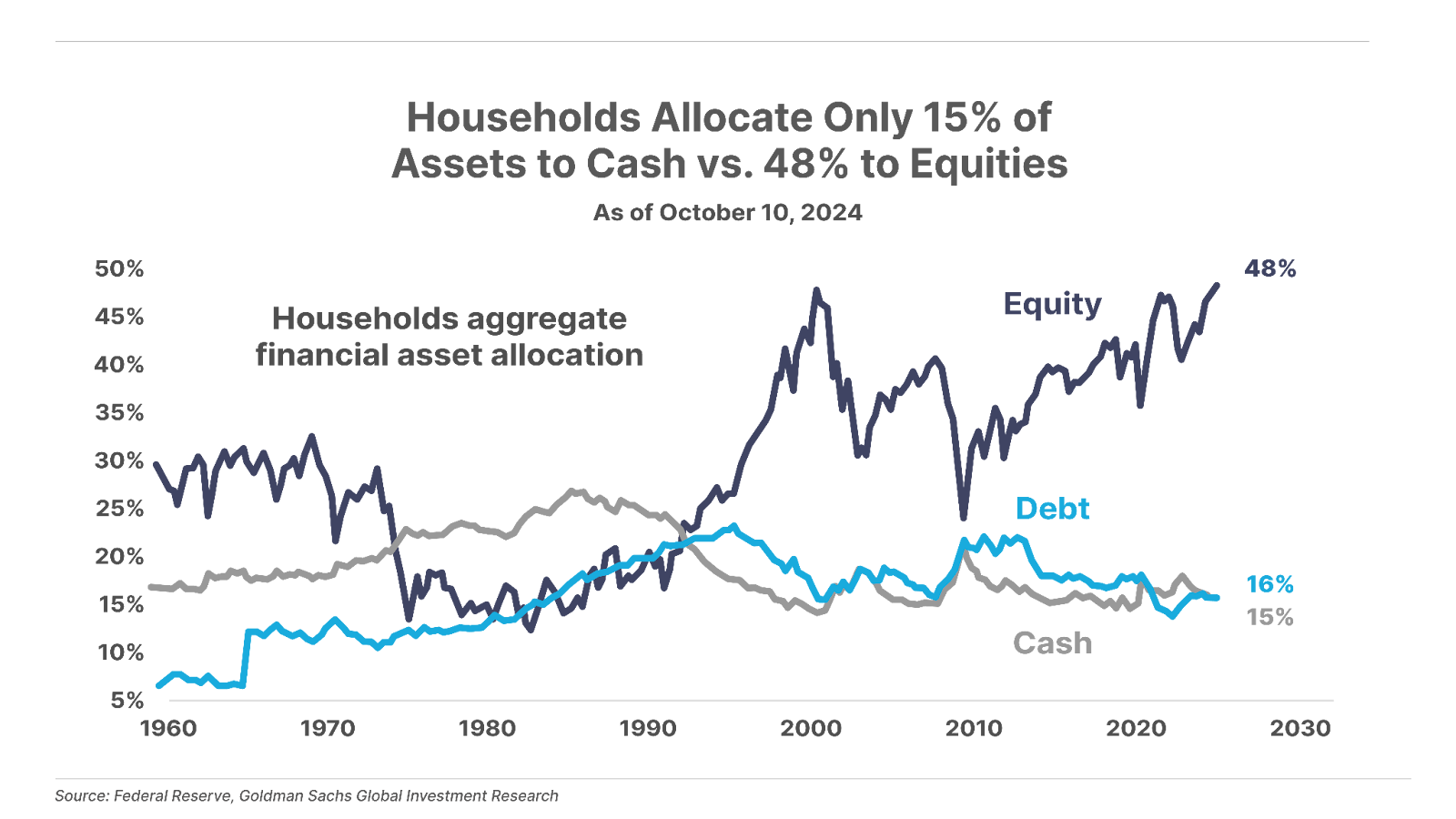

U.S. households are all-in on the stock market, with the highest allocation – at 48% – to stocks as a percentage of total financial assets, since the dot-com bubble more than 20 years ago. All too often, it’s households – mom-and-pop investors – that suffer the most in a market correction… And what’s more, enthusiasm for the stock market by small investors is often viewed by “sophisticated investors” as a bearish signal. The flip side of households holding a lot of shares, of course, is that they have less cash to put to work into the market (a trend that’s borne out globally as well, as we explained in Friday’s “Sign of a top”… another bearish sign.)

Government Lies: The “Master Manipulation” to Finance World War I

War isn’t cheap. It isn’t today – America’s foray into Afghanistan from 2001 to 2021 cost an estimated $2.3 trillion. And it wasn’t in 1914, when the British government was looking to borrow the equivalent of a full year’s total domestic output (that would be $24 trillion (!) in current U.S. economic and currency terms) to prepare for the Great War effort.

Britain’s plan was to blockade the Central Powers (that is, the military alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire) with its commercial and naval forces. It needed supplies and arms. And it needed to support the efforts of its allies. As the wealthiest country amongst the Allies – including also France and Russia (and, in 1917, the U.S.) – the burden of funding the war effort fell to Britain. (All told, government spending wound up rising 12-fold during the war.)

So the UK government went to the local bond market, in an effort to raise £350 million – at the time, about 14% of the country’s total economic output (that would be like the U.S. government trying to borrow, in today’s dollars and economic terms, $4 trillion – all at once). In addition to appealing to investors’ patriotism, the government offered an interest rate of 4.1% on the 10-year bonds – well above the 2.5% available on other government debt.

And the sale, by all accounts at the time, was a success. On November 23, 1914, the Financial Times reported that the War Loan bond issuance by the UK government was “oversubscribed,” and that the effort was an “amazing result.” It reflected, the paper continued, the strength of “the financial position of the British nation.”

The thing is… it wasn’t. The War Loan fundraising effort was an absolute failure. Britain’s banks and the Bank of England – which wasn’t yet a central bank (more on that later) – had agreed to buy around £100 million of the issuance, with the remaining £250 million slated to be sold to the public. And private investors picked up only around one-third of the allocation that the UK government had anticipated. It turned out that regular British folks weren’t so keen on buying war bonds… even one that paid a significantly higher interest rate.

Fessing up and acknowledging lukewarm enthusiasm on the part of the investing British public for the war effort would have been disastrous. As a 2017 investigation by the Bank of England of the bogus bond issuance explained,

Revealing the truth would doubtless have led to the collapse of all outstanding War Loan prices, endangering any future capital raising. Apart from the need to plug the funding shortfall, any failure would have been a propaganda coup for Germany.

So the UK government did what it – what all governments – do best: It lied. It turned to the Bank of England (not yet a central bank then) to buy the bonds itself with its own reserves, which obscured the purchase by getting the bank’s head cashier and his assistant to put the holding in their own names. The holdings were innocuously classified on the Bank of England’s balance sheet as “Other Securities”… rather than Government Securities, which would have been a dead giveaway.

Only a handful of officials knew what was really going on, including John Maynard Keynes – better known as the father of macroeconomics than as a deceitful employee of the UK Treasury – praised what he called the “master manipulation” of using the Bank of England to obscure the disastrous bond issuance.

And of course it wasn’t the last time that a government buried an inconvenient reality on someone else’s balance sheet. The U.S. Federal Reserve was established in December 1913… And it wouldn’t be until 1946 that the Bank of England was nationalized to become a government entity, rather than one owned by private shareholders.

And it certainly also wasn’t the last time that a government lied to the people it supposedly represents. Like a five year old holding a crayon in front of a white wall covered in Picasso-like squiggles, claiming “It wasn’t me!”, sometimes reality (no one wanted to buy the war bonds!) is precisely the opposite of what the government says (applications to buy are “pouring in”!)

My personal favorite example of government gaslighting: On August 14, 1998, Russian President Boris Yeltsin appeared on television – slurring his words, thanks to vodka or age (or both) – to reassure anxious Russians, who had suffered far more than their fair share of wealth-obliterating devaluations of the ruble already, that…

There will be no devaluation – that’s firm and definite… I’m not simply fantasizing. Everything has been calculated. Every day, work is done to control the situation in this area.

At the time, I (Kim Iskyan) was living in Russia. For months, the country’s bond market – where investors were demanding triple-digit yields – had been telegraphing the complete collapse of the currency. Banks had long since run out of dollars, as desperate ruble owners scrambled to find a way to survive another devaluation. Purchases of new cars hit new highs, as ruble holders looked to spend their soon-to-be-worthless paper currency on something that would retain value. (A local Costco selling gold – as we wrote recently – wouldn’t have been able to keep it on the shelves. Unfortunately for Russians, no Costco… and no gold.)

Sure enough… three days after Yeltsin’s slurry proclamation, the ruble collapsed to half its value – which was just the start of a long, slow, paper wealth-destroying decline. It was, briefly, fat city for people who held dollars, as suddenly (this was before the magic of automated repricing) everything in the store was selling at a 50% discount. And it was economic ruin for tens of millions of Russians.

Politicians lie all the time, of course. America’s politicians do too, as we wrote on Friday… and the tone and tenor rises as election day approaches.

The best way to protect yourself from government lies? For starters… Watch this video. We’ve mentioned this a lot lately… and yes, we have a sales pitch at the end. But even (especially!) if you’re already a paid-up subscriber (or a Partner Pass member), you’ll get a lot out of our presentation. We can’t stop America’s destruction, but we can make people aware of what’s happening – and show them how to protect themselves.

Good investing,

Kim Iskyan

Stevenson, MD

P.S. Porter loves introducing new people to subscribers… Just before last month’s Porter & Co. annual conference, he insisted on adding a new name to the lineup of speakers. His name is Pieter Slegers, a young Belgian man who writes Compounding Quality. It was good that he did.

Pieter focuses on exceptionally high-caliber companies that have big moats and trade at a reasonable price… which, well, is precisely what Porter does too.

He only recently discovered Pieter and Compounding Quality. And he’s never seen someone whose work he’s willing to so wholeheartedly endorse so quickly.

Pieter is one of a kind. While he’s still a young man, he’s got the insight (and performance) of an investor with decades of experience, and following his ideas could make you a lot of money. Look here to see what he has to say about Nvidia (NVDA). And take a look at this to see his list of companies he’d be prepared to hold for decades.

To find out more about Compounding Quality, and get the full portfolio and all of Pieter’s ongoing analysis and recommendations, check out the special offer Pieter has put together exclusively for Porter & Co. It’s a fantastic deal: You’ll receive the Founding Partner package for the price of an annual membership (on the web page link, just select the “Annual” choice, and Pieter will manually upgrade you.)