Issue #20, Volume #1

Porter & Co.’s Marty Fridson Was There

Three Things You Need To Know Now:

1. Loan delinquencies spike at America’s largest banks. New data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”) reveals that the percentage of loans that are more than 90 days delinquent has jumped to 4.85% at America’s largest banks (those with over $250 billion in assets) in Q2, up from 2.4% in Q2 2023. That’s the highest rate of delinquencies since 2011, and is being driven by souring commercial real estate and consumer credit card loans (see below). These are the same big banks (like Bank of America) that own the largest portfolios of underwater U.S. Treasury and mortgage bonds – where losses are growing as interest rates shoot higher. Stress continues building across the banking sector… don’t say we didn’t warn you.

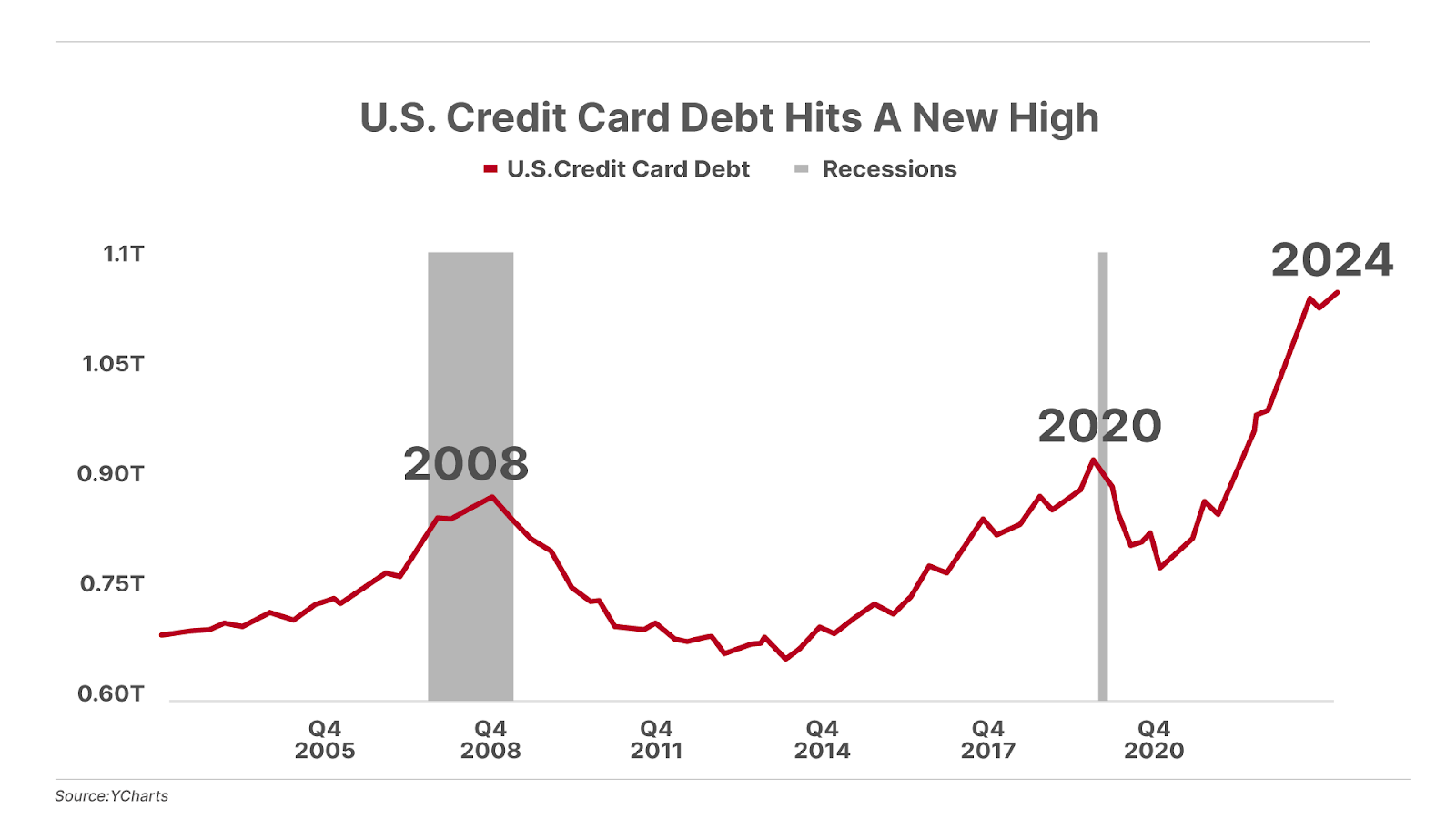

2. Credit card debt hits a new high. U.S. credit card debt is hitting historic levels, far surpassing those seen in the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. Today, American households owe more than $1.1 trillion in credit card debt. To make matters worse, interest rates on this debt have risen to a record high, now 21.8% – which is 38% above the historical average going back to 1970. Not surprisingly, credit card defaults hit a 13-year high of 3.25% in Q2, more than double the delinquency rate three years ago.

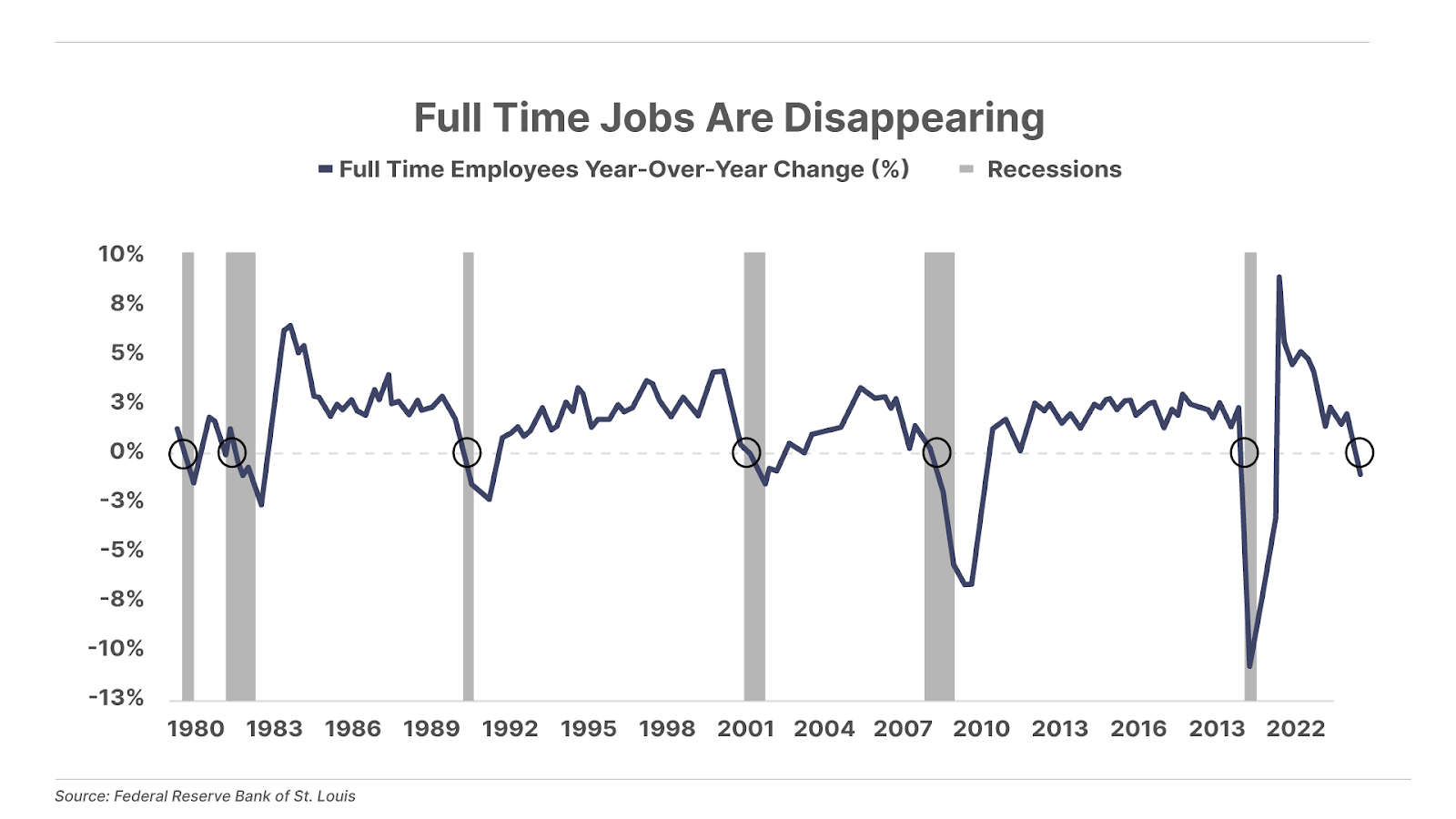

3. Full-time jobs are disappearing. Last week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) reported that the number of full-time employees declined year-over-year in Q3, for the second consecutive quarter. Unlike the rising unemployment rate – which has arguably been influenced by a recent influx of immigrants who have increased the total number of available workers – this number shows unmistakable weakness in the jobs market. And going back to at least 1980 (when this data series began), two quarters of decline have indicated the economy was already in recession. Will this time be different?

And one more thing…

We’ve written about gold a lot recently… as an investment safe haven, as portfolio insurance, as a way to hedge against the decline of the U.S. dollar, and – with the price of gold up 33% this year so far – a compelling investment in its own right. Meanwhile, though, the shares of gold mining companies have been seriously lagging: As we wrote in last week’s Big Secret on Wall Street issue, the benchmark NYSE Arca Gold BUGS Index (HUI), which tracks the shares of gold mining companies, hit an all-time high in 2011. Today – although the price of gold is more than double what it was in 2011, and sitting at an all-time high – the HUI is about half the level as it was back then.

That doesn’t make sense. And it’s a market anomaly that I think will go away soon, as one of the foundational rules of life, money, and the universe – mean reversion – kicks in.

I’m not a gold analyst. Fortunately, I’m friends with Marin Katusa, who is one of the best in the gold business. He and I recently sat down for a wide-ranging conversation about gold and where it’s going… and the best ways to invest in gold today. You can watch it here.

Bonds and Liar’s Poker at Salomon Brothers

On Monday, I interviewed author Michael Lewis, live on stage at the Stansberry Conference in Las Vegas. Lewis, author of Going Infinite (about Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder of busted crypto platform FTX), Moneyball, and The Big Short, wrote his first book about the years he spent as a bond salesman for Salomon Brothers in the late 1980s – at the time, one of the biggest and most powerful investment banks in the world.

Liar’s Poker was an instant best-seller for revealing the (often hilarious, often horrifying) reality behind what was at the time the larger-than-life Ground Zero of free-wheeling American capitalism in its 1980s heyday – the bond trading floor of one of the most venerable Wall Street investment banks… and the fast-evolving, hotter-than-hot niche of mortgage-backed securities.

More than that… Liar’s Poker has for decades been a point of departure – and required reading – for anyone contemplating setting foot on a Wall Street trading floor. It’s inspired countless recent college graduates to ponder a career – or a job, at any rate – in finance.

“Everyone read the book differently. I was just telling a story,” Lewis told me. For some, the book vilified Wall Street. For others, he explained, it glorified the world of trading.

Just a few years before Lewis was at Salomon, flogging bonds and collecting material for his first book, Porter & Co. Distressed Investing analyst Marty Fridson was in another part of the building at One New York Plaza, identifying profitable trade opportunities in the debt market.

This is Marty now…

For me, the larger-than-life personalities on the bond trading floor portrayed in Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker are more than just characters in a spellbinding story… they were the BSDs (read the book!) that were defining a culture of Wall Street at the time. I worked in bond research at Salomon Brothers from 1981 until 1984, and many of the characters in the book were my colleagues.

The firm was in its heyday in the 1980s. CEO John Gutfreund landed on the cover of Business Week with the headline “King of Wall Street.”

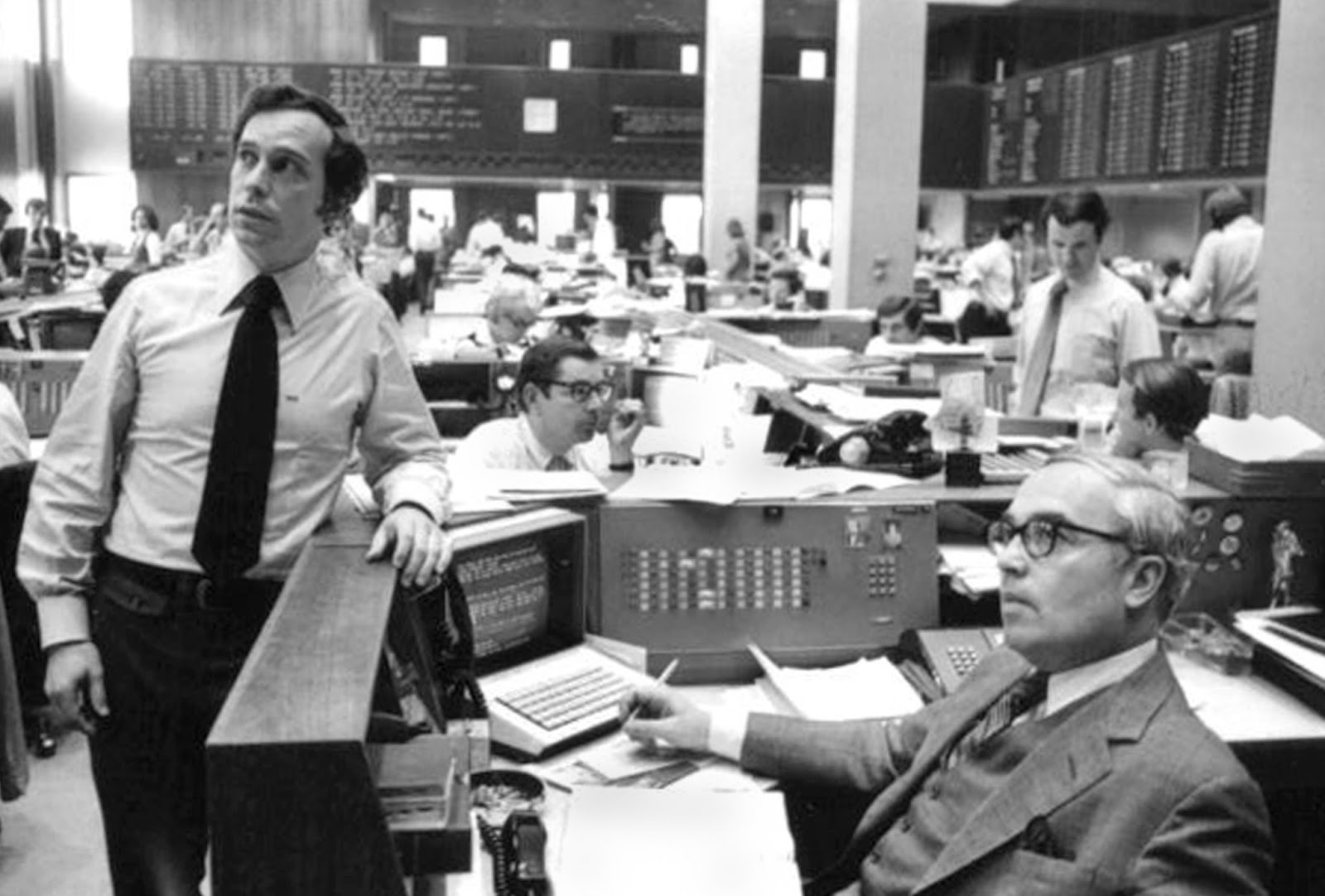

Gutfreund (pronounced “Goodfriend” and seated in the photo below) didn’t fit the image of a Wall Street CEO. His office was next to the rowdy trading floor – so he could get in on the action when he felt the urge.

Back then, trading floors weren’t covered by computer screens filled with colorful charts, endless digits of data, and the down-to-the-millisecond prices of stocks and bonds. There were of course computers – for example, a dedicated share-price machine called the Quotron, and Bloomberg units scattered everywhere. But trades were sealed by traders and salesmen and sales traders shouting to each other across the floor (or through the squawk box), and over the phone with their counterparts at other banks… penciling in orders that got recorded later.

Liar’s Poker gets its name from a poker-like game that Salomon Brothers traders would play, using the eight digits of the serial numbers printed on the front of a one-dollar bill. Usually involving two to around six players, each holding his own one-dollar bill close to his chest, the game would start with one person saying, for example, “three threes,” suggesting that there were at least three threes on all the serial numbers held by all the players.

The game moves clockwise, so the player on the left of the person who started has two options. He can make a higher bid – by throwing out either three of a higher number, “three fours” or “three sevens” – or more of a number like “four twos” or “five sixes.” Or he challenges, in which case the guy who bid three threes would ask everyone to show their bills to see if three threes exist on all the serial numbers of the players’ dollar bills.

If there are three threes, the challenger loses the bet and hands over his dollar (or whatever the bet was). If there are not three threes – and the first player had been bluffing (or “lying”) – the challenger wins the bet. Usually, the wager was the dollar in your hand, but often the stakes were jacked up higher.

As Lewis details in the book, one day, Gutfreund challenged one of Salomon’s best traders, John Meriwether, to an exceptional round of liar’s poker: “One hand, one million dollars, no tears.” (Adjusted for inflation, that’s around $3 million in today’s dollars.)

Traders regularly wagered hundreds of dollars. But a million? Never.

The game of liar’s poker is similar in a sense to trading bonds, in that it revolves around risk and probability: Is the potential payoff worth the risk?

In this case, Meriwether – who rose to the top of the most cut-throat trading floor on Wall Street thanks in part to his keen ability to compute the risk/reward tradeoff of a trade, or situation – knew it was not, because he’d lose either way. If he won, he’d make his boss look bad. If it lost… he’d be out $1 million.

So, as Lewis recounts, Meriwether shot back: “I’d rather play for real money. Ten million dollars. No tears.”

Gutfreund forced a smile, said, “You’re crazy,” and walked away.

Gutfreund personified the scrappy culture of high-stakes bond trading. Making it in that world requires nerves of steel, plus strong convictions about value that you’re prepared to back up with the capital entrusted to you.

Then, as is the case today, many bonds trade very infrequently, so prices are produced only when a transaction is in the works. Traders have to calculate a bond’s true value on short notice by comparing similar trades of similar issuers with similar maturities. And when the market is gyrating wildly, and an eager buyer is on the line, they must decide on a price in a matter of seconds, with the firm’s risk managers hovering nearby.

For example… suppose you and I both have positions in a bond of XYZ Corporation. Hoping to add to my position in a bond that I see upside in, I ask what price you want for your XYZ bonds. You reply, “95¾,” with the face value being 100. I say “too high,” citing the levels at which several recent trades occurred in comparable bonds, calling them by their nicknames: “Sobell 8s just traded at an 8.25% yield. Telephone 7⅞s got lifted at 97½”.

But you refuse to budge – possibly because you paid a higher price for it and want to unload your position on a guy (and they were all guys then) who’s “off his market”…

I’m not that guy, though. “Okay,” I say. “I’ll make you a two-sided market. I’ll buy your bonds at 95 or I’ll sell you mine at 95½. Tell me what you want to do.”

Walking away from this challenge is not an option. You’d lose credibility within the trading community. “Hitting the bid” – selling your bonds to me at 95 – will be a painful loss. Your trading profit for the year directly affects the size of your annual bonus. But buying mine would likely be throwing good money after bad – you’d have more of the bonds that you are trying to unload. It’s a real-life liar’s poker game of risk versus reward.

A bond trader’s personal financial well-being is on the line every minute of every trading day… and beyond. Unlike the stock exchange, the over-the-counter bond market – direct dealer-to-dealer trading by phone rather than in one central exchange – has no official opening or closing time. I saw trades consummated in bars, like Harry’s of Hanover Square, a favorite watering hole of Wall Street traders.

John Gutfreund carried this tough-as-nails trading style into his management of Salomon Brothers. Every Monday morning, he ran a meeting with the head of each desk giving market color and highlighting major positions he wanted the salespeople to focus on unloading. As each desk head spoke, Gutfreund ferociously challenged comments he disagreed with. Anyone who strayed from facts or logic risked getting ripped to shreds in front of the entire firm.

The head of one trading desk told me there were only two things he could possibly do if Gutfreund ever challenged him during his part of the meeting. “One is to say, ‘John, I quit!’ and walk out of the room,” he said. “The other is to fall on the floor clutching my chest and wait for the medics to carry me out on a stretcher.”

He’d rather quit or fake a coronary than face Gutfreund’s wrath.

Fortunately, the ordinary investor doesn’t have to operate under the intense pressure that made Salomon Brothers the top bond house in those days. But developing a keen sense of value and backing up your convictions with serious money can produce handsome profits in a personal portfolio, just as it can for a world-famous investment bank.

Marty is the best in the distressed investing business. He’s seen it all… from the legendary bond trading floor of Salomon Brothers, to the high-yield research teams at a who’s-who of Wall Street banks. And now he’s leading Porter & Co.’s Distressed Investing advisory. Month after month, Marty and his team have shown that distressed bonds – the right distressed bonds – are a fantastic place to put your money. And as the U.S. economy deteriorates, we’ll be entering a sweet spot for buyers of the debt of troubled companies. If you’re not already a subscriber to Distressed Investing… see what we’re talking about here, or call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447, for more information on becoming a subscriber.

Good investing,

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, MD

P.S. Who do you think will win the U.S. presidential election?

The two candidates differ on a range of policies. But one arena in which they agree – or seem to agree, as they’re both carefully ignoring the issue – is the rising federal debt. At $35.8 trillion – up an incredible $473 billion over the first three weeks of October! – it’s arguably the biggest issue facing America. And it’s one that no one’s talking about.

I am, though… and not long ago I sat down with economist and Mises Institute Fellow Peter St Onge to talk about what comes after the elections. We discuss issues that are avoided in the mainstream media because… the solutions won’t sit well with the financial sheeple who are listening to the talking heads. I urge you to hear what we have to say.

Mailbag

As always, let me know what you think, by emailing me at [email protected]. I’d love to hear from you!

Today’s letter comes from P.T., who writes:

Hi Porter,

I am a Porter & Co. partner and Stansberry Alliance member. I love your work at Porter & Co.

I have a question which puzzles me. At the breakout session on Tuesday at the Stansberry Conference & Alliance meeting, which you co-hosted with Austin Root of Stansberry Asset Management, you commented that you think equities will fall when interest rates go up again. I understand that concept, but am struggling to reconcile it with the proposition that ownership in stocks of great companies is the only way to beat inflation. Can you comment on this?

Thank you, P.T.

Porter’s comment: There’s a very well-proven (and logical) link between the 10-year Treasury bond yield, which is commonly thought of in financial circles as the “risk free” rate of return, and the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of the stock market. Right now, stocks (the S&P 500) are trading at 27x earnings. If you invert that number, you get the S&P 500’s earnings yield: 1/27 = 3.7%. Stocks normally have a “risk premium” over bonds, meaning with a Treasury bond yield of 4.2%, you’d expect to see the stock market’s earnings yield higher than that.

So it’s logical that if rates keep going higher, stocks, eventually, are going to go lower. My belief that stocks are the best form of asset protection isn’t a prediction of current equity prices. It’s based on the reality that through things like the Great Depression and WWII, stocks were the very best way to avoid government confiscation and government’s constant debasement. And I’m sure that’s still true. If you own stocks, you’ll keep your wealth over the next decade. That doesn’t mean I don’t expect the S&P 500 not to have a lot of ups and downs in the meantime.