How to Profit From America’s Decades-Long Infrastructure Boom

This Company Unlocks Premium Pricing Power From Selling Commodities

| Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email Lance, our Customer Care Concierge, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at: [email protected]. Paid subscribers can also access this issue as a PDF on the “Issues & Updates” page here. |

“I can’t f***ing believe this is allowed.”

… so muttered fund manager Steve Eisman “a thousand times” as he uncovered layer after layer of fraud and deception permeating America’s housing market between 2006 and 2007.

Eisman was no stranger to financial chicanery. He got his start on Wall Street analyzing the shady underbelly of American finance – subprime-mortgage lenders, a business model built on making home loans to borrowers at high risk of not repaying their debts.

Eisman made a name for himself by doing something most Wall Street analysts shy away from – advising his clients to “sell” instead of “buy.” And he did it with no reservations. He once walked into the middle of the trading floor at Oppenheimer & Company (where he worked as an analyst) and made an announcement: “The following eight stocks are going to zero.” He listed the eight companies, all of which eventually went bust.

| The Big Secret This company’s distribution advantage unlocks premium pricing power from a commodity product by meeting the needs of its customers. It’s the most powerful feature of its business model, and one that most investors don’t fully appreciate, but that should drive high profit margins over the next decade. |

The problem was, Eisman’s cynicism didn’t help drum up much business for the investment banking firm he worked for. They were in the business of helping corporations raise capital – not bash their stock prices. So in 2004, Eisman launched his own hedge fund, FrontPoint Partners. He was then free to bet against bad business models instead of simply writing reports about their inevitable demise. His previous experience with subprime lenders in the 1990s made him the perfect candidate to bet against what became the mother of all manias: the subprime-housing bubble of the early 2000s.

When Eisman was analyzing subprime lenders in the 1990s, they were a tiny piece of the overall mortgage market. Back then, $30 billion a year in new subprime loans was a big deal. But by 2000, that number surged to $130 billion, before ballooning to $625 billion in 2005. Eisman knew that a lot of bad loans were being made, and that the companies making them would eventually go belly-up.

Eisman bet against the subprime-mortgage craze by shorting stocks like New Century Financial – one of the leading originators of subprime mortgages. But the reward did not necessarily outweigh the risk. The most Eisman could make was 100% if a shorted stock went to zero. Even those profits got eaten away, as short sellers had to pay a 20% dividend to the shareholders they borrowed stock from in order to bet against it. Plus, short sellers had to pay a 12% interest rate along the way. This meant Eisman had to shell out $32 million per year for the privilege of holding a $100 million short position. Meanwhile, if the shares increased in value, he faced the prospect of unlimited losses.

Then in February 2006, a Deutsche Bank trader named Greg Lippmann introduced Eisman to a different way of betting against the subprime-mortgage market. Credit default swaps (“CDS”) provided a form of insurance against a subprime-mortgage meltdown. They offered the ability to bet directly against the subprime loans being issued, instead of against the companies that were making the loans.

The upshot was that buying CDS contracts could produce returns of as much as 1,000% on an original investment. The lopsided return proposition stemmed from the fact that the banks selling the insurance contracts had grossly mispriced the odds of a subprime bust. Eisman was elated, describing the conversation he had with trader Lippmann:

“When he walked in and said you can make money shorting subprime paper [from buying CDS contracts], it was like putting a naked supermodel in front of me.”

Over the next 18 months, Eisman and his crew explored the underbelly of Wall Street’s subprime machinery. He learned how Wall Street, with help from the ratings agencies, packaged low-grade mortgages into AAA-rated fixed-income securities known as mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”). And how even lower-quality bonds were packaged into collateralized debt obligations (“CDO”). The credit default swap contracts he purchased provided a way to profit if these loans went bust.

The deeper Eisman dug, the more incredulous he became. For instance, he learned that bonds were being made from mortgages, known as “no-doc” loans, for which no documentation was required about the borrower’s job history, income, or assets. As Eisman explains…

“The first time I realized how bad it was, was when I said to Lippmann, ‘Send me a list of the 2006 deals with high no-doc loans… I figured Lippmann was going to send me deals that had 20% no docs. He sent us a list and none of them had less than 50%.”

That meant that half of all mortgages were being granted to borrowers who provided no proof of their ability to repay the loans. This lack of oversight is how Wall Street’s subprime machinery allowed borrowers to take out more money than they could ever repay. Eisman discovered loans like one made to a strawberry picker in Bakersfield, California, who had income of $14,000 per year, and yet was able to secure a loan to purchase a $724,000 house.

Early on in the housing boom, these loans didn’t go bust because borrowers paid rock-bottom interest rates for a short period – before the rates contractually reset at higher levels a few years down the road. Before then, though, with home prices rising, borrowers could refinance for more than the original value of the property, receiving a cash infusion that enabled them to keep making their monthly payments. It was a perfect Ponzi scheme – homeowners, mortgage issuers, and investment bankers would all get rich if home prices kept moving higher.

But Eisman figured it was only a matter of time before home prices peaked, and interest rates reset at higher levels, triggering a wave of defaults. It was obvious, he thought – why could no one else see what’s coming?

What kept the bubble from bursting was the complicity of the ratings agencies.

Eisman discovered how corrupt the ratings agencies had become in facilitating the sale of these subprime mortgages through mortgage-backed securities. The agencies rated a substantial portion of bonds as AAA, or as good as U.S. Treasuries, based on a series of what proved to be ludicrous assumptions they plugged into their ratings models.

After personally meeting with analysts at the ratings firms, Eisman learned that the models used to rate bonds assumed borrowers’ ability to pay back the loans would be unaffected by their mortgage rates resetting at higher levels. He also learned that the models had no input for a drop in home prices. They assumed, like many on Wall Street, that U.S. housing prices couldn’t go down. Eisman was shocked by each new revelation, as he recalled:

“I cannot f***ing believe this is allowed. I must have said that one thousand times.”

Along the way, in typical Eisman fashion, he didn’t hesitate to express his views on the situation. During a financial conference in Hong Kong, the chairman of HSBC bank claimed that the losses in his bank’s subprime portfolio would be “contained.” Eisman stood up from the audience and responded, “You don’t actually believe that, do you? Because your whole book is f****d.”

Eisman couldn’t believe how even the supposedly “smart money” sitting at the top of the global financial system was sleepwalking into disaster. And he grew giddy about the prospect of cashing in on their ignorance. As he explained the situation to a coworker, he said:

“It’s a gold mine. And nobody else knows about it.”

By January 2007, Eisman (pictured below) had placed an all-in bet on what he expected to be a housing armageddon. His fund had purchased $550 million in credit default swaps against subprime-mortgage bonds, believing that the bonds would quickly lose value. By June 2007, subprime-mortgage bonds began selling off slowly, and then suddenly. FrontPoint’s positions began moving up in value by hundreds of thousands of dollars each day, and then by millions.

Over the following year, these positions produced a windfall for his fund investors as the subprime-bond market entered into freefall. Eisman’s fund ballooned to $1.5 billion, netting his investors $1 billion in profits.

Today, Eisman is more optimistic about the future of the U.S. economy – going long more often than he shorts. In particular, there’s one major theme that he’s betting heavily on, which we’ll dive into in this issue.

Eisman’s Next Act: The Big Long

In a June 2023 interview on the Bloomberg Odd Lots podcast, Eisman made the case for what we’re calling the Big Long, in reference to the 2015 Big Short film that profiled a group of fund managers, with Eisman as a major character, who profited from the collapse of the housing market in 2007-2008.

Eisman believes there are huge profits to be made from the record influx of capital reshaping and revitalizing America’s industrial infrastructure over the next decade. This includes $2 trillion in stimulus spending from the federal government, plus trillions more from the private sector.

The first big theme driving this trend is the rise of onshoring, which involves U.S. manufacturers bringing their overseas operations back home. This trend began gathering momentum in 2018 after the Trump administration imposed a series of tariffs and import duties that upped the cost of outsourcing U.S. manufacturing to China.

The COVID-19 outbreak and economic turmoil that resulted massively accelerated this trend. The pandemic-driven supply-chain disruptions revealed the extreme reliance U.S. corporations had on overseas suppliers, for everything from computer chips to pharmaceuticals.

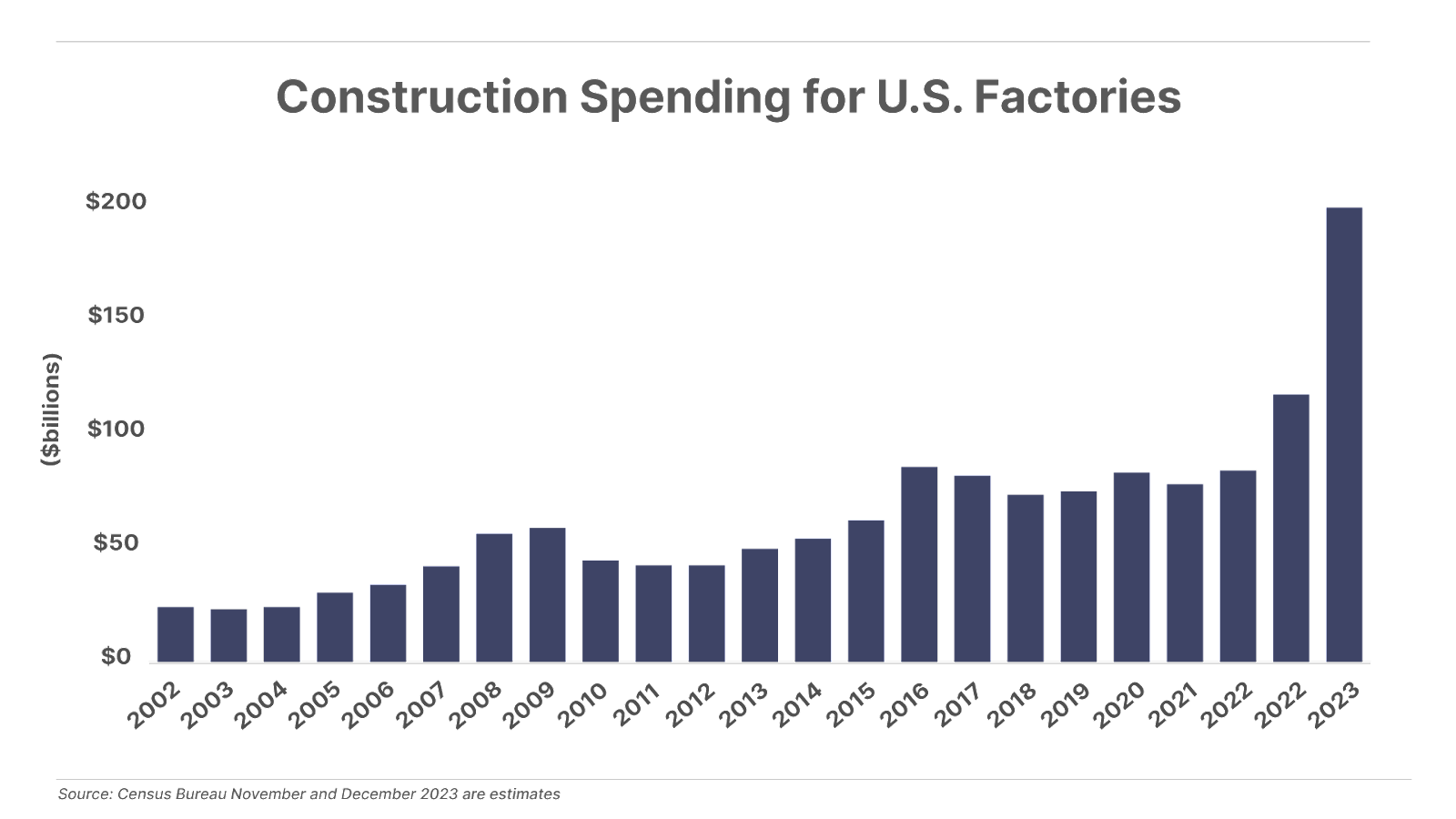

As a result, U.S. companies across many industries are pouring record amounts of capital into domestic manufacturing facilities. In the last three years alone, $500 billion of investment has gone into new U.S. factory construction, compared with about a total of $200 billion over the previous three-year period:

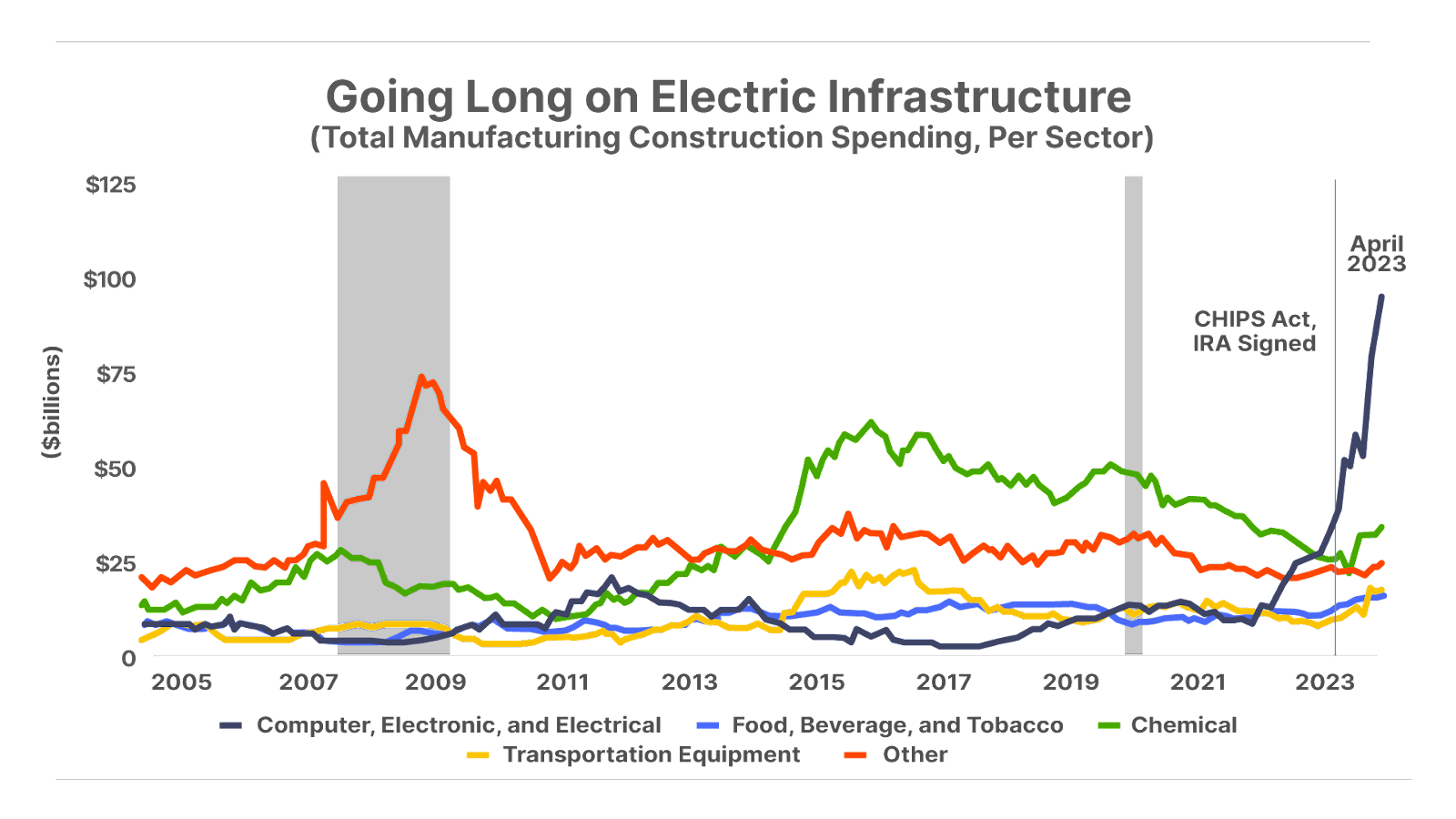

Within this manufacturing bonanza, one area in particular is benefitting the most – investment into computers, electronics, and electrical power transmission:

Three major factors are driving the building boom in this sector:

- The rise of electrified transport (i.e., electric vehicles and charging stations) and “green” power generation (i.e., solar and wind power).

- The artificial-intelligence (“AI”) revolution that’s fueling a boom in U.S. semiconductor manufacturing and data-storage centers.

- The dire need to overhaul America’s flailing electric grid in response to the massive new electrical infrastructure needs from the two trends noted above.

We’ll dive deeper into each of these three segments later. For now, the key is that all of these trends are being turbocharged by $2 trillion in federal grants and incentive programs launched in 2021 and 2022. These include the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act (“CHIPS”), the $579 billion Inflation Reduction Act (“IRA”), and the $1.2 billion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (“IIJA”):

Together, these three pieces of legislation represent the largest infrastructure stimulus program in American history. And we’re still in the very early stages of this infrastructure bonanza, with most of this money still slated to be allocated over the next decade.

In this issue, we’re recommending our best idea for capitalizing on this decades-long infrastructure boom.

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.