Issue #66, Volume #2

A Bond Is Only As Good As The Business That Underlies It

This is Porter’s Daily Journal, a free e-letter from Porter & Co. that provides unfiltered insights on markets, the economy, and life to help readers become better investors. It includes weekday editions and two weekend editions… and is free to all subscribers.

| High-yield telecom bonds produced negative-67% in 2002… Bond issuers need strong cash flow to support interest payments… “The biggest and fastest rise and fall in business history”… Selling puts can be an effective income-generating strategy… Look how magnificent the Magnificent 7 is… |

Today, Porter turns the Journal over to Distressed Investing senior analyst Marty Fridson.

Marty has a long background in trading, investing, and finance… Investor’s Digest called him “the most well-known figure in the high-yield world.” Over a 25-year span with Wall Street firms including Salomon Brothers, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch, he became known for his innovative work in credit analysis and investment strategy.

In today’s Journal, Marty talks about understanding the real degree of risk in bonds and other investments.

Here’s Marty…

Sometimes the risk you need to worry about has to do with things much more basic than a ratio derived from a company’s financial statements or a zig-zaggy pattern on a technical chart.

Here’s a cautionary tale on that theme.

At the beginning of 2000, telecommunications was the largest industry in the U.S. high-yield bond universe, accounting for 20% of total market value. Its performance over the next two-plus years was disastrous. Through June 2002, high-yield telecom bonds produced a negative-67% total return versus a positive-10% for the non-telecom sector.

The default rate on telecom debt skyrocketed during that period. To make matters worse, investors recovered less of their principal on telecom debt issues than on defaulted bonds of any other industry. Because of its performance, telecom ranks last out of 35 industries in recoveries on defaults for the entire 1983-2024 period. Its 26% average recovery on senior unsecured bonds compares with a 38% median and an 82% rate for the top-ranked industry.

My heads-up to high-yield investors about the flaws of the telecoms that went belly-up wasn’t a case of Monday-morning quarterbacking. Their high susceptibility to bankruptcy was apparent to me well ahead of time, even if the market eagerly continued doing deals. My conclusions weren’t based on detailed analysis of the companies’ financial statements. Rather, the risks should have been seen by anyone with a basic understanding of corporate finance.

Up until the late 1990s, high-yield bond portfolio managers were very clear about what they looked for in an issuer: Strong cash flow to support required interest payments and solid asset values to ensure the highest possible recovery of principal in the event of default.

The new breed of telecom issuers represented the opposite of that model. Many were “business plan” companies. They not only lacked profits and cash flow, but weren’t even generating meaningful revenue. Most of these companies had little in the way of physical assets that could be sold to pay off creditors if they went bust.

Many early-stage companies were seeking to capitalize on telecom deregulation and exciting new technologies. In these circumstances, it’s normal for there to be a lot of competitors, but only a few survive. Between 1900 and 1908, for example, 502 companies entered the new business of car manufacturing. Just a handful – Ford Motor, General Motors, and Chrysler, the most notable – lasted through the eventual industry shake-out. A similar win-loss rate was taking place in the early-stage telecoms.

The inevitability of thinning of the herd hit me forcefully at a Merrill Lynch high-yield conference in the late 1990s. During a break, I heard two young analysts comparing notes on the presentation they’d just seen. One analyst said to the other:

I like the company, but I don’t really understand how it’s different from the one in the session before that.”

Presenters were telling investors,

We provide business-to-business telephone service. We go into the same office buildings as that other company, but we service a distinctly different set of customers.”

To believe that all of the paging and cell-phone service providers would still be around in a few years, you had to assume we would all be walking around with four or five handheld devices.

Those issuers didn’t belong in the public bond market – which is where mature and proven companies went for capital to expand without giving away equity in the company. Telecom start-ups should have been financing themselves with venture capital (“VC”) – the VCs expect most companies they invest in to be losers. They earn their returns from the huge upside in the small minority of winners. Buyers of a new bond at par, on the other hand, have very limited upside – a guaranteed set interest rate – and huge downside if the company goes bankrupt.

And many did. In the 18-month period leading up to June 2002, there was $110 billion of telecom bankruptcies. The Economist called the industry’s experience “the biggest and fastest rise and fall in business history.”

Here are some of the most spectacular flameouts:

WorldCom, Global Crossing, and Allegiance Telecom all – and many top executives either went to jail or settled suits because of bad accounting practices… Many other telecoms also went bankrupt, including At Home Corporation, 360 Networks, and PSINet.

The above-mentioned 26% average recovery on telecoms underscores how great that downside can be. The 26% recovery figure means that if you paid par ($1,000) for one of the bonds that defaulted, your bond was worth $260 after things settled out, so you lost 74% of your principal.

The telecom craze’s mismatch of issuers and investors resulted from an excess of investment capital. Overstimulation by the Fed was the underlying cause – rates were low, so money was cheap. In the equity sphere, the excess of capital pulled a lot of insufficiently mature dot-coms into the public market. Early-stage telecoms were the bond market analogue. Eyeing huge fees, the investment banks obligingly lowered their underwriting standards.

The silver lining in the high-yield telecom fiasco of 2000-2002 is a lesson that’s useful beyond the specialized field of high-yield bonds. Bonds are usually a safe bet… unless the underlying business isn’t generating the cash to service the debt. And selling puts can be an effective income-generating strategy… as long as the puts are on companies with business models that make sense.

You can reduce the risk of winding up on the wrong side of one of these trades by stepping back from the financial minutiae and the technical charts. Make certain the company is in a reasonably stable competitive environment. If a shakeout is still underway – or hasn’t yet begun – you’re not just facing a risk of the share price dropping by 10% or 20%. If the stock went public before its time, you could see it go to zero. Just keep in mind how those early-stage telecoms and dot-coms vanished almost overnight a quarter-century ago.

To learn more about trading techniques that are safe, simple-to-understand, and profitable, click here to get on the waiting list for Porter & Co.’s new Trading Club. Once you are in, you can be part of the next round of trading in the coming weeks.

Three Things To Know Before We Go…

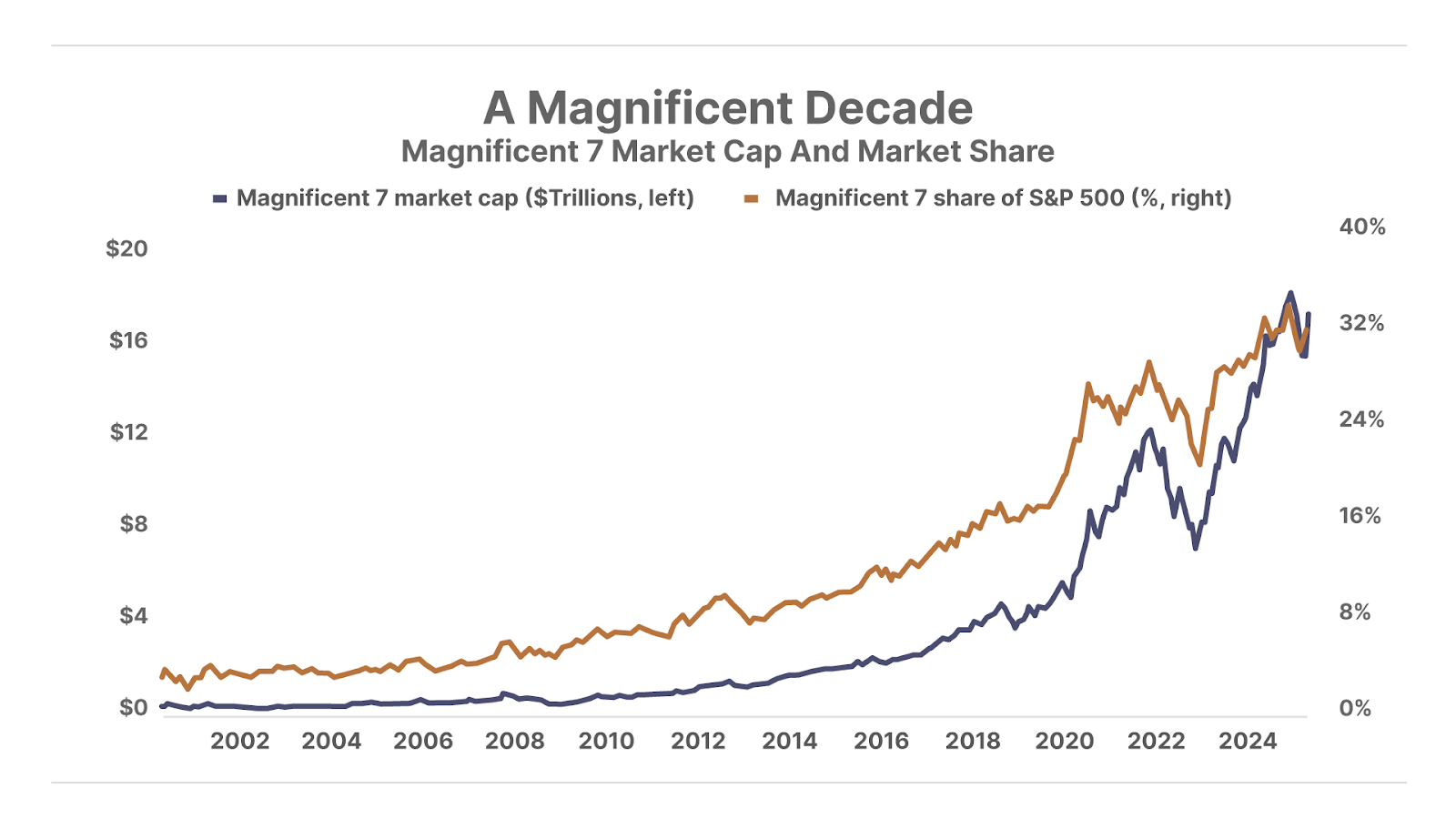

1. The rich get richer. The Magnificent 7 – the stocks of the most dominant giant tech companies – have delivered an average return of more than 4,900% over the past decade. Meanwhile, the other 493 companies in the S&P 500 have barely budged – 7% annualized or 106% total returns. A decade ago, the Mag 7 – Alphabet (GOOG), Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL), Meta Platforms (META), Microsoft (MSFT), Nvidia (NVDA), and Tesla (TSLA) – made up just 10% of the S&P’s value. Today, their combined $16.7 trillion market cap accounts for nearly a third. The valuations are well-deserved: they are global tech leaders with massive scale, strong financials, and dominant platforms. But the risk cuts both ways. A major stumble – whether from regulation, disruption, or failure – could send shockwaves through the entire index.

2. Is the buyback “well” running dry? S&P 500 firms authorized a record $717 billion in share buybacks through the first five months of 2025, already exceeding the total authorizations for all of 2024. However, while companies’ plans to repurchase shares are surging, actual buybacks have been slowing. As you can see below, quarterly buybacks through Q4 2024 are down more than 13% from their 2022 peak, suggesting companies’ ability to finance these their massive intentions may be drying up.

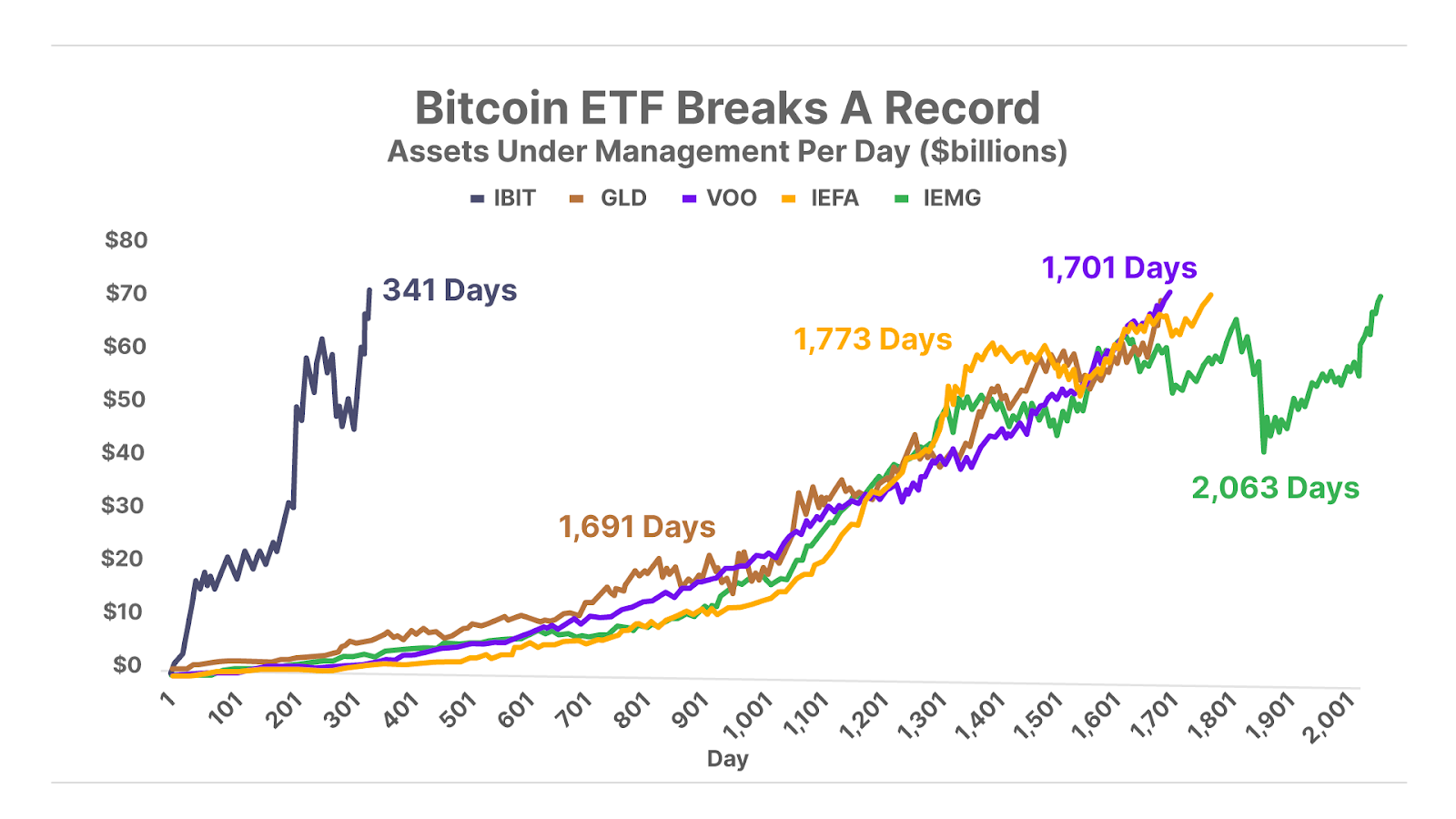

3. Bitcoin breaks a record. This morning, the largest Bitcoin exchange-traded fund (“ETF”) – the iShares Bitcoin Trust ETF (IBIT) – became the fastest ETF in history to surpass $70 billion in assets under management (“AUM”). It achieved this milestone in just 341 trading days, nearly five times faster than the previous record of 1,691 days set by the SPDR Gold Trust (GLD) in 2011.

And One More Thing… Poll Results

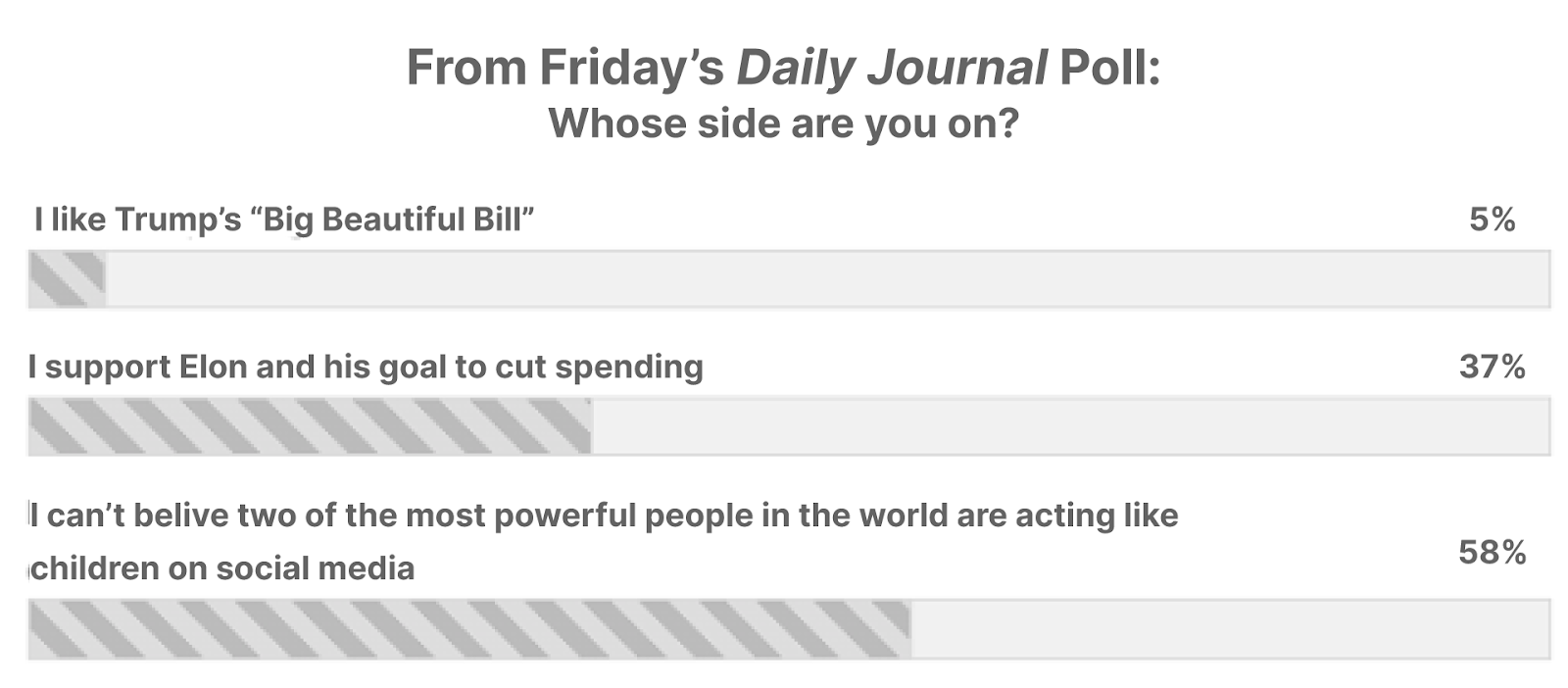

Following President Donald Trump and Department of Government Efficiency head Elon Musk’s very public and very heated social media spat over the GOP tax bill last week, we asked readers on Friday: “Whose side are you on?”

While 37% chose “I like Elon and his goal to cut spending” and 5% went with “I like Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill,’” the majority of survey takers – 58% – went with the third option provided: “I can’t believe two of the most powerful people in the world are acting like children on social media.”

Mailbag

We’ve received a great deal of positive feedback about the newly launched Trading Club, with nine of our 11 initial positions in the green to date. Subscribers have also enjoyed the educational component of the service, including the video presentation (with Porter, CEO Jared Kelly, and lead analyst Ross Hendricks) we put together to explain the inaugural trades in our live $100,000 trading account.

The first note comes from Bob J., who writes:

Guys, I just want to say the trading video is a terrific addition to this service, for several reasons.

The two most interesting items it revealed for me:

Patience: when and how to use patience when selecting an order price to get filled at. The video shows that sometimes you want to fill the order now, and sometimes you are willing to let the order sit for a bit, and explains why.

The nuance of selecting the strike price, and why you may want the price to be more in the money or just out of the money.

These candid conversations are invaluable to me, as a person who learns best by listening and watching.

Congratulations and well done! Keep on keeping on!”

And this note from Steve P.:

Excellent video presentation. Everything was clearly explained and demonstrated. I appreciate the nuance of adjusting either the strike price or the premium as market conditions change while executing each trade. That answered a concern I had.

Great job by all!”

This last note from Robert M. raises the question of whether we plan to take profits on a trade that’s moved sharply in our favor within just a few days:

Will you ever consider exiting a position early if it moves quickly after opening?

For example, the British American Tobacco (BTI) calls moved 50% higher after a couple of days. I would think a 50% gain after a short time on a long-term position is a good idea. We could always re-enter. Just wondering.”

Ross Hendricks’ comment: It’s a great question, and it hits on one of the most important aspects of successful trading. That is, fighting the natural temptation to take a quick gain on a position and hope to re-enter at lower prices.

Having tried that same tactic myself on many occasions, I’ve learned the hard way that it’s the single most expensive mistake a trader can make. The problem is, the market doesn’t always provide the re-entry opportunity you’re hoping for. In which case, you risk missing out on a home-run trade that can make or break your returns for an entire year.

The market doesn’t provide many opportunities to make 1,000% or more. And that’s exactly the opportunity we believe we’ve found in our BTI call options, if the shares hit our price target of $70 to $80 by the option expiration date.

But the only way we will ever capture a 1,000% return is by not selling when the trade is up 50% or 100%. And that means resisting the temptation to out-trade the market, and instead simply sitting tight when you have a winning position on your hands.

Legendary trader Jesse Livermore said it best, in the iconic book Reminiscences Of A Stock Operator:

After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: It never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It always was my sitting. Got that? My sitting tight! It is no trick at all to be right on the market. You always find lots of early bulls in bull markets and early bears in bear markets. And their experience invariably matched mine, that is, they made no real money out of it. Men who can both be right and sit tight are uncommon. I found it one of the hardest things to learn. But it is only after a stock operator has firmly grasped this that he can make big money. It is literally true that millions come easier to a trader after he knows how to trade than hundreds did in the days of his ignorance.”

To get on The Trading Club waiting list, click here.

Tell me what you think: [email protected]

Good investing,

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, Maryland

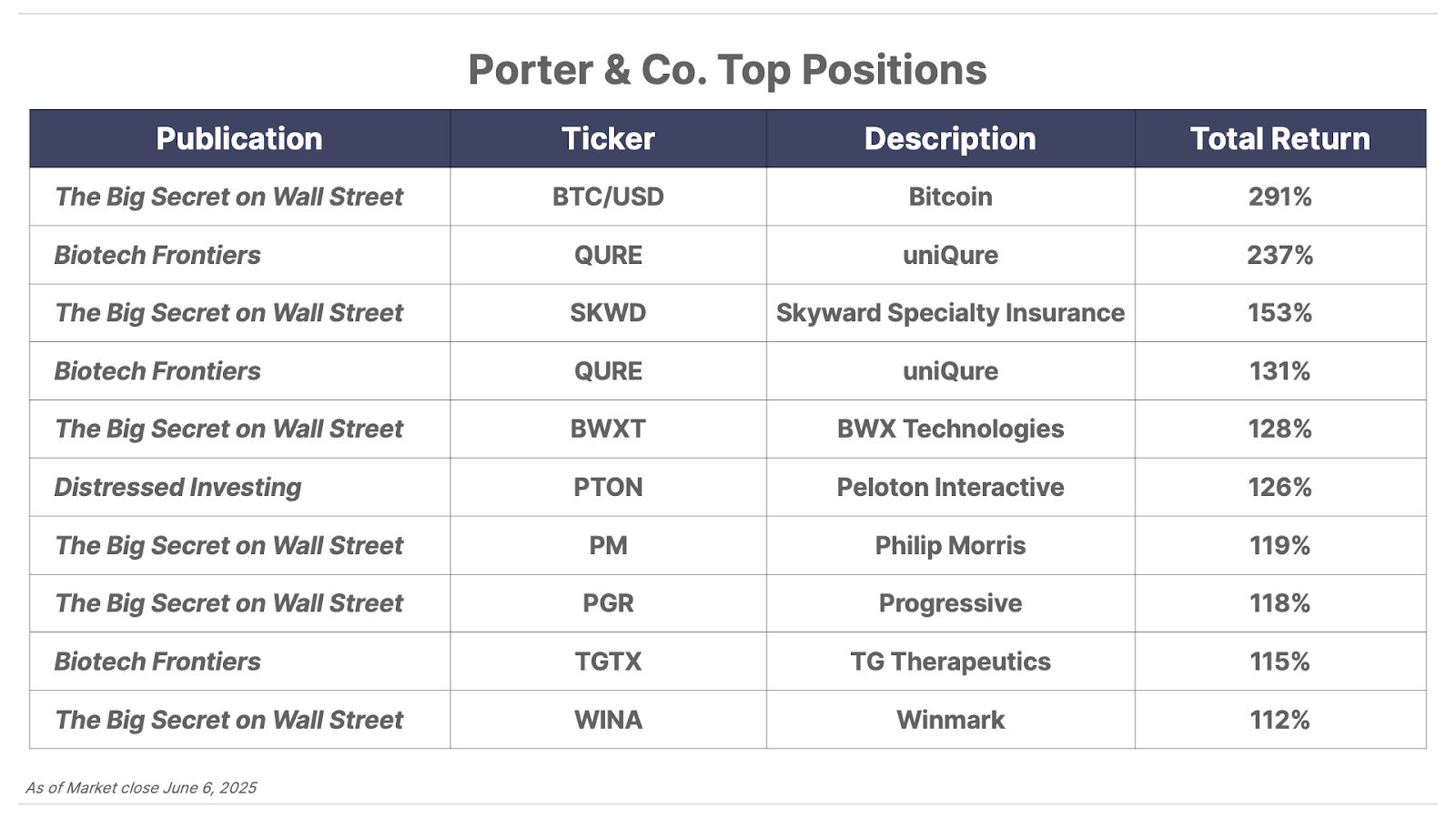

Please note: The investments in our “Porter & Co. Top Positions” should not be considered current recommendations. These positions are the best performers across our publications – and the securities listed may (or may not) be above the current buy-up-to price. To learn more, visit the current portfolio page of the relevant service, here. To gain access or to learn more about our current portfolios, call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447.