Issue #85, Volume #2

When A Sound Concept Overstays Its Welcome

This is Porter’s Daily Journal, a free e-letter from Porter & Co. that provides unfiltered insights on markets, the economy, and life to help readers become better investors. It includes weekday editions and two weekend editions… and is free to all subscribers.

| How a sound investment concept can get out of control… Private credit emerged after the Global Financial Crisis… Now they are offered in ETFs… LBOs in the 1980s followed a similar trajectory… Only time will tell whether private credit will escape that fate… The spending will never stop… Kinsale earnings explained… |

Editor’s note: Today, Porter turns the Journal over to Distressed Investing senior analyst Marty Fridson.

Marty has a long background in trading, investing, and finance… Investor’s Digest called him “the most well-known figure in the high-yield world.” Over a 25-year span with Wall Street firms including Salomon Brothers, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch, he became known for his innovative work in credit analysis and investment strategy.

In today’s Journal, Marty talks about the remarkable growth in the private-credit market over the last decade… and how it might be getting out of control.

Here’s Marty…

Private credit has entered the “excesses” phase.

Many new Wall Street investment categories follow a familiar trajectory:

It starts with a sound concept, hits rapid growth, then expands into excesses, followed by blowout, and then possibly reform and revival… or not.

Ominously, private credit moving into the excesses phases is coinciding with the product becoming increasingly available to ordinary investors through exchange traded funds (“ETF”). The story is instructive to both debt and equity investors.

Private credit is indeed a sound concept. In the aftermath of the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, U.S. banks tightened lending standards, cutting back on new loans in order to repair their damaged balance sheets. That created a huge new growth opportunity for private credit funds. These are pools of capital that invest primarily in loans to non-public companies. Many companies that didn’t meet the banks’ raised bar to qualify for loans turned to this investment vehicle instead.

Up until the last few years, private credit funds lent only to small- and medium-sized companies, but now they compete directly with banks and the public bond market with offerings of $1 billion or more. Many distressed companies have turned to private credit funds for loans to help them through a potential crisis point, such as to pay off a large chunk of debt coming due.

The rise, fall, and resurrection of high-yield bonds in the 1970s and 1980s follows the pattern that currently appears to be playing out in private credit.

In the late 1970s, investment banks initiated something almost unheard of up until that time – newly issued bonds with speculative-grade ratings (BB or lower). Before then, almost all bonds BB or lower were “fallen angels” – issued with investment-grade ratings of BBB or higher, but later downgraded to “junk.”

This innovation widened the range of financing options for companies that didn’t qualify for investment-grade. Additionally, ordinary investors could now obtain higher income on their savings, without taking irresponsible risks, by owning shares of high-yield bond mutual funds that diversified across many different low-rated issues.

So far, so good.

But Wall Street has a habit of taking a good idea too far. That occurred during the 1980s. Another innovation, leveraged buyouts (“LBO”), became a major source of the issuance required to meet the mushrooming institutional demand for the lofty yields offered by speculative-grade debt. As the buyout firms competed to offer the highest equity returns to their limited partners, the equity components of the LBOs’ capital structures shrank to levels that made defaults all but inevitable once the inevitable next recession hit.

Until that happened, high-yield investors enjoyed lofty returns. But there were some question marks about the prices underlying those returns. These bonds traded primarily over-the-counter – through broker-dealer networks – rather than on an exchange. Many traded infrequently, enabling market-makers to slow-walk the lowering of their bids and offers to reflect credit quality deterioration in bonds underwritten by their firms.

The monkey business went as far as “parking” crimes, which landed “junk-bond king” Michael Milken in prison. To hide the fact that a bond manager had bought a bond that tanked, Milken’s firm Drexel Burnham Lambert’s trading desk bought out his position prior to the quarterly date for reporting performance to clients. Drexel agreed to sell it back after quarter-end at a prearranged price. That’s illegal and it also results in inaccurate transaction prices.

As the 1990 recession approached, default rates soared, especially on the overleveraged buyouts. In what became known as the Great Debacle, returns collapsed and not a single high-yield new issue came to market during the last 10 months of 1990.

Following that Great Debacle, with Drexel out of business, the surviving underwriters raised their standards and the high-yield market recovered. It’s now many times larger than it was in the 1980s and has become a mainstream asset class for institutional investors.

Revival may be the ultimate fate of private credit, which is paralleling the high-yield market’s history… or maybe not.

Once again, the financial innovators who dreamed up private credit began with a sound idea: Non-bank companies can provide quick-response, customized loans to small and medium-sized companies, particularly those facing a temporary strain that makes traditional bankers wary.

So successful has private credit become that the lenders have moved up from small- and medium-sized companies to corporations large enough to access the public debt market. At the latest high-yield bond conference that I annually run for the CFA Society New York, Melissa Brady of Alvarez & Marsal, reported that the $1.7 trillion private credit is projected to grow to $3 trillion by 2029. That will make it twice as large as the U.S. high-yield bond market, which has been around several decades longer.

This success has been accompanied, Brady reported, by excessive leveraging of the market’s weaker credits. So much debt has been put on companies funded by private credit that they’re at near-term risk of default in increasing numbers. Rating agency Fitch reported that of the private companies it monitors, the percentage failing to cover their interest charges by even 1.0x jumped from 7% in Q1 2024 to 17% as of May 2025.

In addition, borrowers are playing games with their financial reporting by calculating key financial ratios with a lot of addbacks. (“That item cost us some money, but we’re going to call it a one-off and say it doesn’t count.”)

As with high-yield bonds in earlier times, the prices that are the basis for calculating private credit returns are often dubious. There’s little organized trading of the loans by which to establish transaction-based prices, so pricing is left to the fund managers’ judgment. Their judgment may be that their returns will look better if they don’t pay much attention to mounting risk of default.

It all adds up to a possibility of a blowout in private credit in the inevitable next recession, echoing the 1989-1990 high-yield Great Debacle. But it’s not a certainty that private credit will afterwards arise phoenix-like and fly to even greater heights. One example of a Wall Street innovation that didn’t come back from a near-death experience is the once-thriving market in collateralized bond obligations (“CBO”). Those were packages of high-yield bonds, somewhat like the ones that constitute mortgage-backed securities. The creators’ overly aggressive tactics caused CBOs to lose too much credibility to recover from the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Only time will tell whether private credit will escape that fate.

If you’re not already a subscriber to Distressed Investing… call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447, for more information on becoming a subscriber.

You will buy these four miners (now or when the herd panics)

BREAKING: Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” Passed – which guarantees the U.S. will add another $10 trillion to its already massive debt pile. This means big beautiful gains are coming to the best gold miners – because gold runs higher and longer in times of out of control monetary inflation.

Click here to learn about the four “Golden Anomaly” miners selling at discounts up to 90% below the value of their gold in the ground.

Three Things To Know Before We Go…

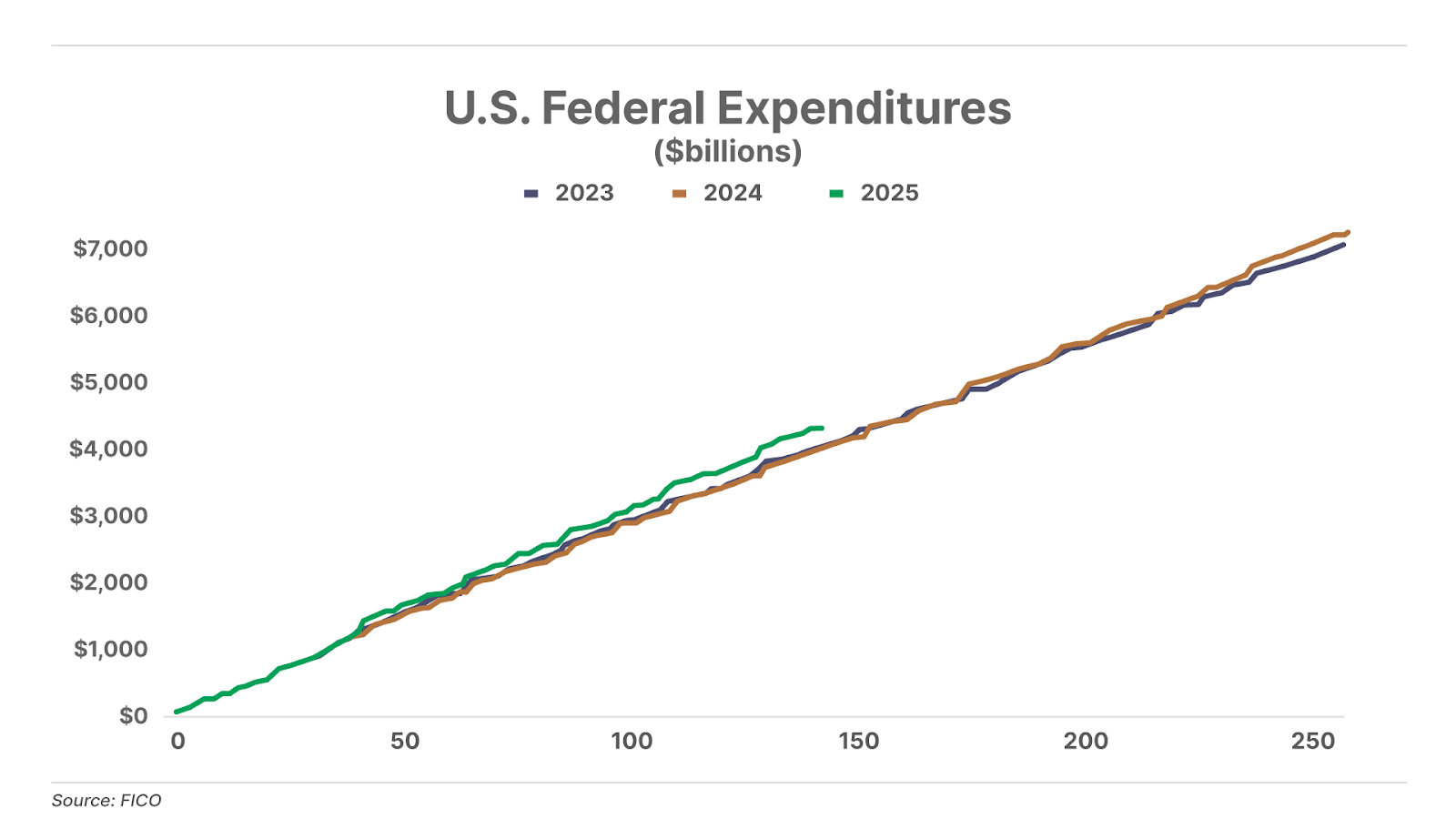

1. Margin debt reaches a new high. In June, the reported margin balances in U.S. investor accounts represented the largest monthly increase ever, jumping $87 billion to reach an all-time high of just over $1 trillion. The prior peak of $936 billion was reached in late 2021, just before stocks entered into a bear market in 2022. It’s the latest sign of the growing speculative frenzy in today’s market.

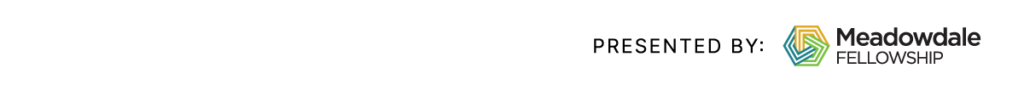

2. Durable Goods Orders post their sharpest decline since COVID. Durable Goods Orders fell 9.3% in June following May’s 16.5% surge, largely due to a 22.4% drop in transportation equipment orders. Excluding transportation, core orders rose 0.2%, above expectations, signaling modest resilience in manufacturing demand. However, non-defense capital goods orders, excluding aircraft, a key gauge of business activity, fell 0.7% for the first time since February. While businesses remain active, they are being more cautious with new investments amid looming tariffs and rising input costs.

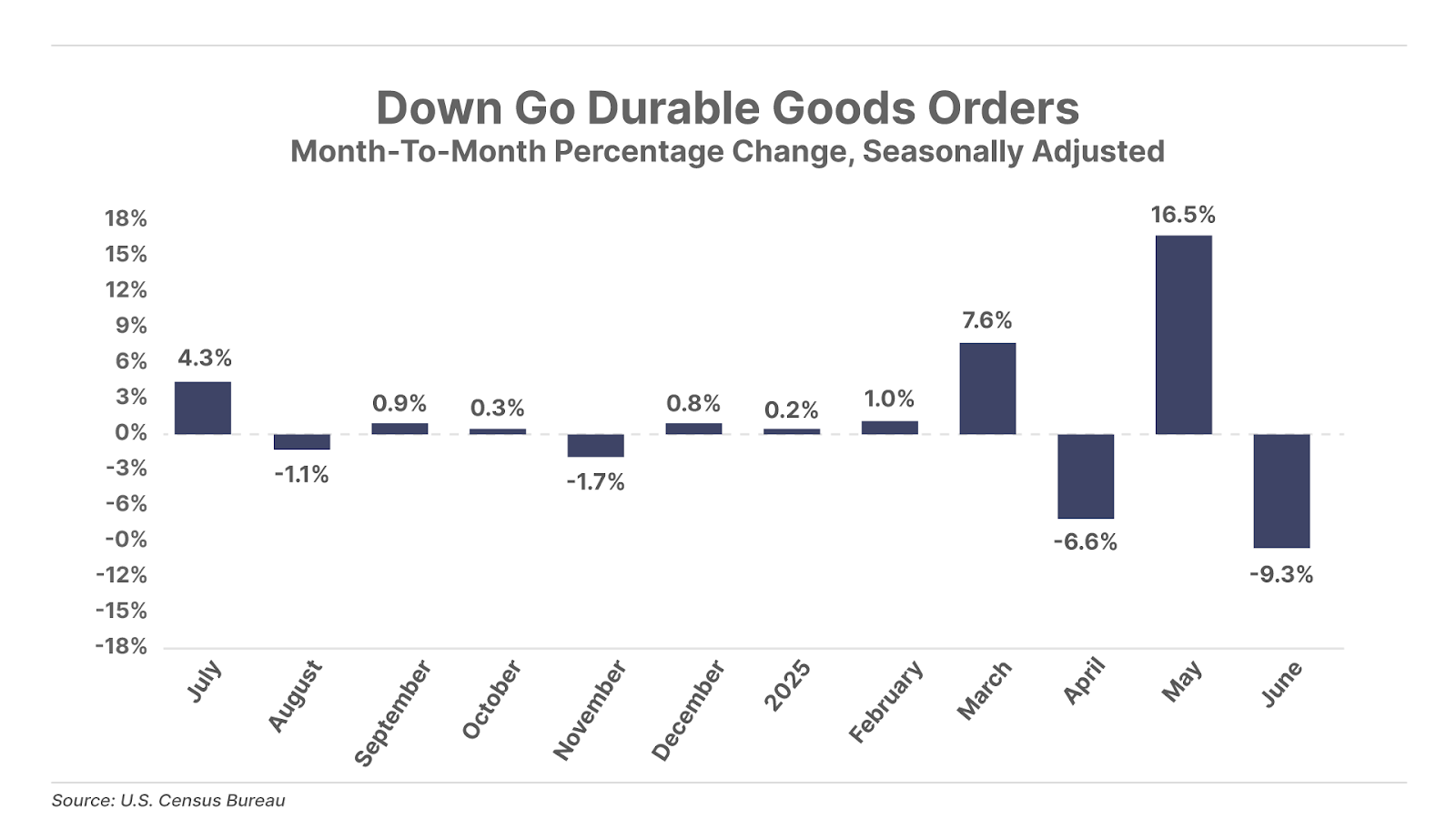

3. DOGE is officially dead. When President Donald Trump took office for the second time in January, many hoped his Department of Government Efficiency (“DOGE”) would do what no administration has done in decades: cut government spending. However, while DOGE initially promised to cut $2 trillion from the federal budget, the department itself admits it has saved less than 10% that total to date… a paltry $190 billion, with several outside sources putting the real savings at a tiny fraction of even that reduced figure. Meanwhile, real-time data shows federal spending is actually higher year-to-date than it was in either of the past two years. Repeat after us: The spending will never stop.

And One More Thing… Kinsale Capital Earnings News

Kinsale Capital (NYSE: KNSL) released another stellar report for its Q2 earnings yesterday… but instead of the usual post-earnings plunge we expected, the stock actually went up.

While our hopes for buying the stock cheaper didn’t pan out, long-term investors should be pleased. Net income jumped 45% year-on-year to $5.76 per share, while the combined ratio remains best-in-class at 75.8%. Some critics may take issue with the slowdown in premium growth of just 4.9%. But we don’t. We see this as underwriting discipline. Kinsale doesn’t write bad business. Look at the recent big losses from the Palisades fires. The E&S market leader, Arch Capital (which was a long term holding of Porter’s at Stansberry Research), lost $550 million. Kinsale’s losses? $22 million.

Kinsale continues to do more business and earn more profits, with better underwriting and more and more efficient operations. It’s the industry’s clear leader. While trading around earnings can be fun and occasionally lucrative for traders, this latest episode confirms the one thing we know for sure: buying and holding world-class companies is the surest path toward long-term wealth.

Moral of the story: predicting short-term stock prices is a guessing game.

Tell us what you think… good, bad, or indifferent: [email protected]

Good investing,

Martin Fridson

New York, New York

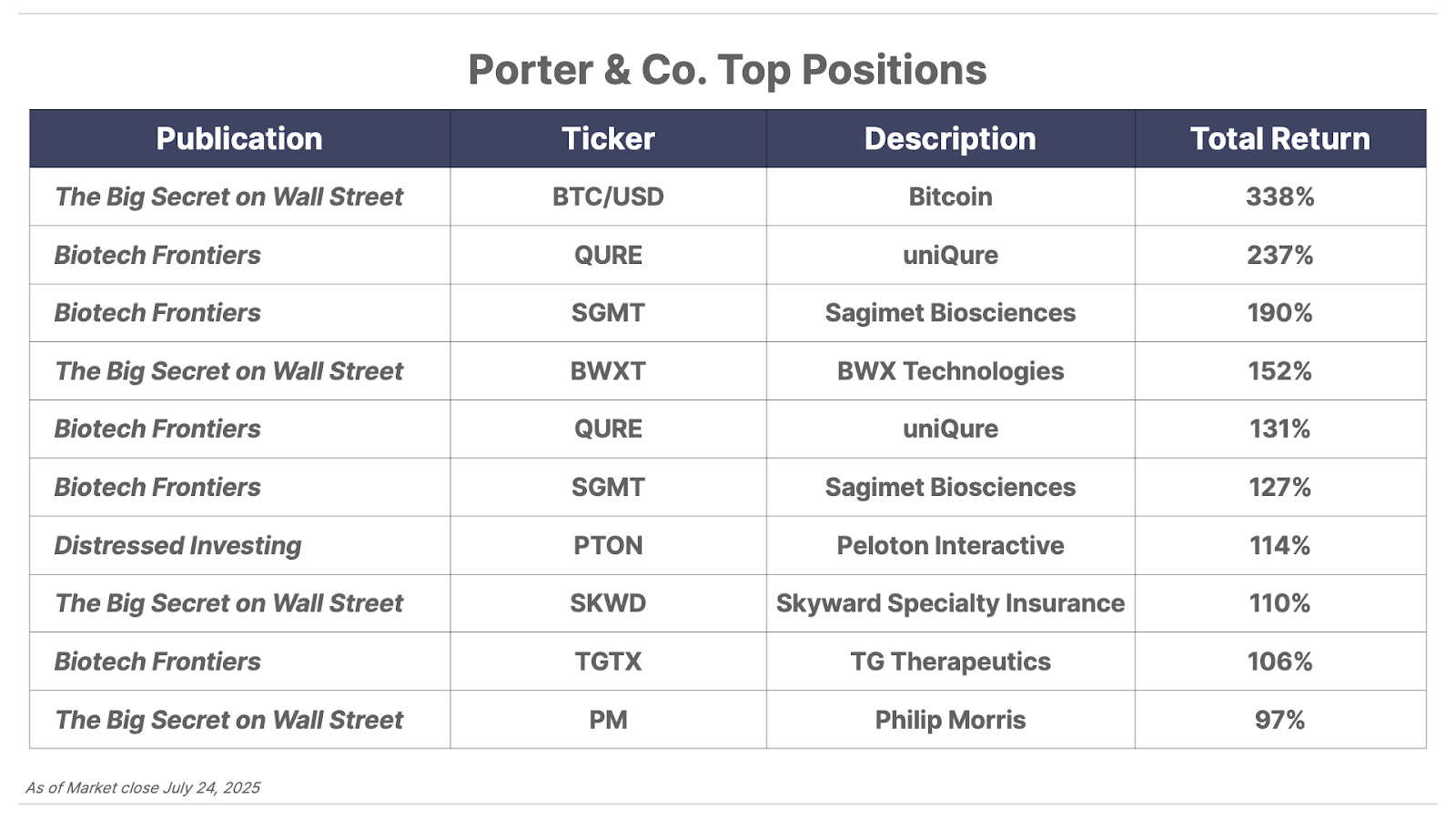

Please note: The investments in our “Porter & Co. Top Positions” should not be considered current recommendations. These positions are the best performers across our publications – and the securities listed may (or may not) be above the current buy-up-to price. To learn more, visit the current portfolio page of the relevant service, here. To gain access or to learn more about our current portfolios, call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447.