Charles Schwab May Not Go Bust…

But Some of Its Investors Might

It’s entirely possible that David Grusch saw a few aliens.

But they most likely climbed out of a whiskey bottle, not a flying saucer.

Grusch is the “UFO whistleblower” who made headlines last year with his claims that the U.S. government is hiding alien spaceships. Apparently, he also has a serious substance abuse problem… as investigative journalist Ken Klippenstein recently discovered using a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request to access Grusch’s police records.

Perhaps the truth about the little green men is more likely to be found “in rehab” than “out there.”

We wouldn’t know this – or any of thousands of other formerly hidden bits of info, both serious and not-so-serious – if not for a quiet, bespectacled U.S. Congressman named John E. Moss.

Moss was the architect of FOIA – which took him 10 years to coax through Congress, under the disapproving glare of several presidents. Under FOIA (passed into law in 1966), U.S. citizens can request – and receive – a wide variety of previously unreleased government documents at state and federal levels. It’s often described as the law that keeps Americans “in the know” about their government, and – as long as you know what to ask for – you can use FOIA to find out quite a lot.

During his 25-year tenure in public office, John Moss managed to tick off his colleagues on both sides of the political aisle. (President Lyndon B. Johnson, who grudgingly signed FOIA into law, complained that the act was likely to “screw the Johnson administration.”) In defiance of his doubters, Moss was fanatically committed to transparency… and to supporting the interests of the average American citizen.

Moss didn’t stop with FOIA. He spearheaded the Consumer Product Safety Act of 1972, which regulated the contents of household products so people could be sure they weren’t handling harmful ingredients. And he was responsible for the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act of 1975, a piece of legislation that made it much tougher for car dealers to sell lemons.

And – perhaps most impressively – in 1975, he opened up the stock market for retail investors. (Without Moss, we here at Porter & Co. would likely have a very different business model today.)

Prior to that year, securities traded at fixed commission rates – and the commissions were so high that the average Joe typically couldn’t afford to participate. Most stock market traders, back then, were deep-pocketed tycoons and institutions. (You’ll recall that something very similar happened once upon a time in the airline industry.)

But Moss’s groundbreaking Securities Act Amendments of 1975 abolished these high fixed rates and opened them up to competition, which in turn, made it much easier for normal folks to invest in stocks.

Moss’s legislation effectively deregulated the stock market – a watershed moment for trading and investing worldwide.

And it was that moment when the Charles Schwab Corporation (SCHW), the first “regular-people” broker, got its start.

San Francisco-based Charles (“Chuck”) Schwab had been in the traditional brokerage business for a few years. But, following the passage of the Securities Act, Schwab realized he could now slash his fees, market aggressively to retail investors, and become the nation’s go-to “discount broker.”

Schwab charged half of what regular brokers did, made the decision to stay open 24/7 – and soon his phones were ringing off the hook, to the detriment of his competitors.

It was a winning strategy. Today Schwab is the U.S.’s largest publicly traded brokerage company, holding over $9 trillion in client assets. (Our publisher and CEO, Kim Iskyan, has fond memories of opening his first trading account there many years ago.)

But while Schwab is still best known as a discount broker, its business has changed quite a bit since those early days in the 1970s.

The Discount Broker That Isn’t

Today, Schwab offers a number of additional financial services, including asset management and retail banking services like checking and savings accounts and home mortgages.

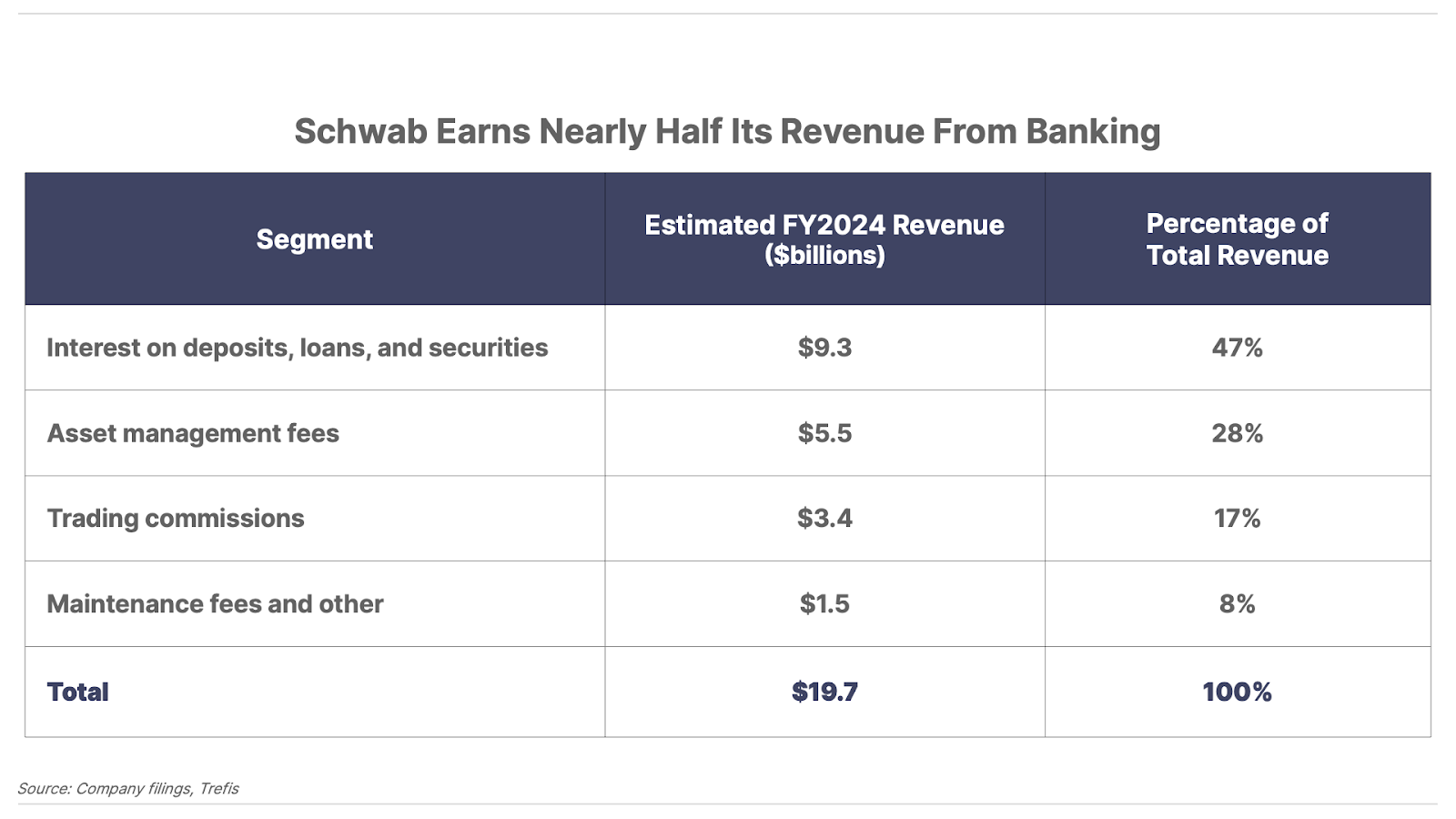

As you can see below, Schwab’s banking services business now generates almost 50% of its total annual revenue. Meanwhile its traditional brokerage segment – which over the decades became a highly competitive business, to the point where today most brokerages, including Schwab, don’t even charge commissions for basic equity trades – accounts for less than 20%.

In other words, Schwab is more a bank than a brokerage firm today. And that could ultimately spell trouble for its shareholders in the years ahead.

The 2023 Banking Crisis Hasn’t Been Resolved

Longtime Big Secret on Wall Street readers may recall the “perfect storm” of conditions that brought the American banking system to the brink of disaster last year.

Following COVID, when the U.S. government unleashed trillions in fiscal stimulus and the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates to the lowest levels in history, many banks invested heavily in low-yielding long-term bonds. These primarily included long-term U.S. Treasury bonds and longer-duration “agency” debt – issued by government-sponsored entities (“GSEs”) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and typically backed by mortgages.

At the time, this arguably made some investment sense. While these bonds were yielding a paltry 1% to 2% a year, it was far more than the 0% investors could earn in short-term Treasury bills and money-market funds. And because the Fed forecasted that interest rates were unlikely to rise meaningfully for years, there appeared to be little in the way of interest rate risk.

Of course, as we know now, the Fed (and many investors) were dead wrong. The trillions in COVID stimulus caused inflation to soar… and the central bank was forced to carry out one of the most aggressive rate-hike cycles in history.

The Fed raised short-term rates by more than 500 basis points in less than 18 months – from nearly 0% in March 2022 to 5.25% in August 2023. And this sharp rise in rates caused the market value of long-duration debt to plunge.

Before we proceed, a quick review of “bond math”: As you may know, bond prices move inversely to bond yields (which are driven by interest rates).

For example, when a bank buys a newly issued 10-year Treasury note that yields 1%, the bond price starts out at par value (100 cents on the dollar). If the interest rate in the market moves higher to 2%, then the price of the old 1% bond falls. That’s because there’s no incentive for investors to buy a 1% yielding bond at par value, if they can instead buy a bond with the higher 2% rate. So, the price of the old 1% bond falls to the point where it will generate returns equal to the 2% bonds in the current market.

Generally speaking, the longer the duration of a particular bond, the more its price fluctuates based on a given move in interest rates.

If an investor is able to buy and hold a Treasury bond until maturity, those short-term price gyrations don’t matter – the bond will always get repaid at 100 cents on the dollar when it matures, regardless of its market price in the interim. But if an investor needs to sell a bond before it matures – say, like a bank with a skittish deposit base – it’s possible to lose a lot of money when interest rates move sharply higher.

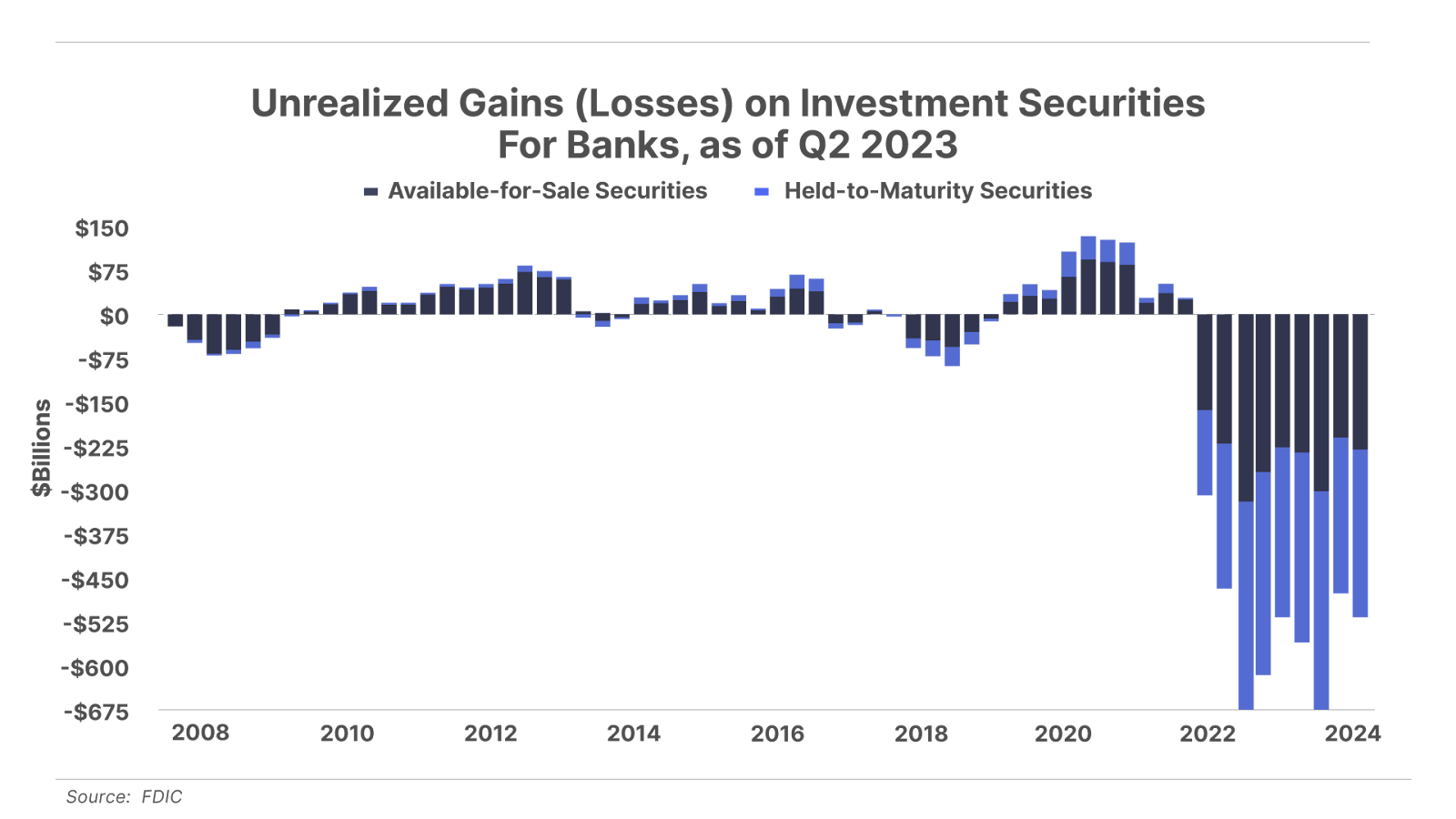

At the peak of the banking crisis last spring, U.S. banks were sitting on nearly $700 billion in unrealized losses from their holdings of “risk-free” Treasuries and agency debt.

As word of these losses spread – and customers realized they could now earn significantly higher yields on their cash in short-term Treasury bills or money-market funds – many people withdrew their deposits. This forced several banks to sell those Treasury holdings and realize losses, quickly making them insolvent.

Following the high-profile failures of several banks in March, including Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) and Signature Bank, the government stepped in to stop the panic with its Bank Term Funding Program (“BTFP”). BFTP allowed banks to temporarily swap their underwater bonds for cash, which in turn reassured depositors and prevented the bank run from spreading further.

However, while the Fed’s bailout halted the acute phase of the crisis, it didn’t actually solve the underlying problem. Interest rates remained (and remain) well above their COVID lows, which meant those unrealized losses didn’t go away.

Today, U.S. banks are sitting on more than $500 billion in unrealized losses in these securities.

And Charles Schwab is one of the worst offenders…

A Problem Bank in Disguise

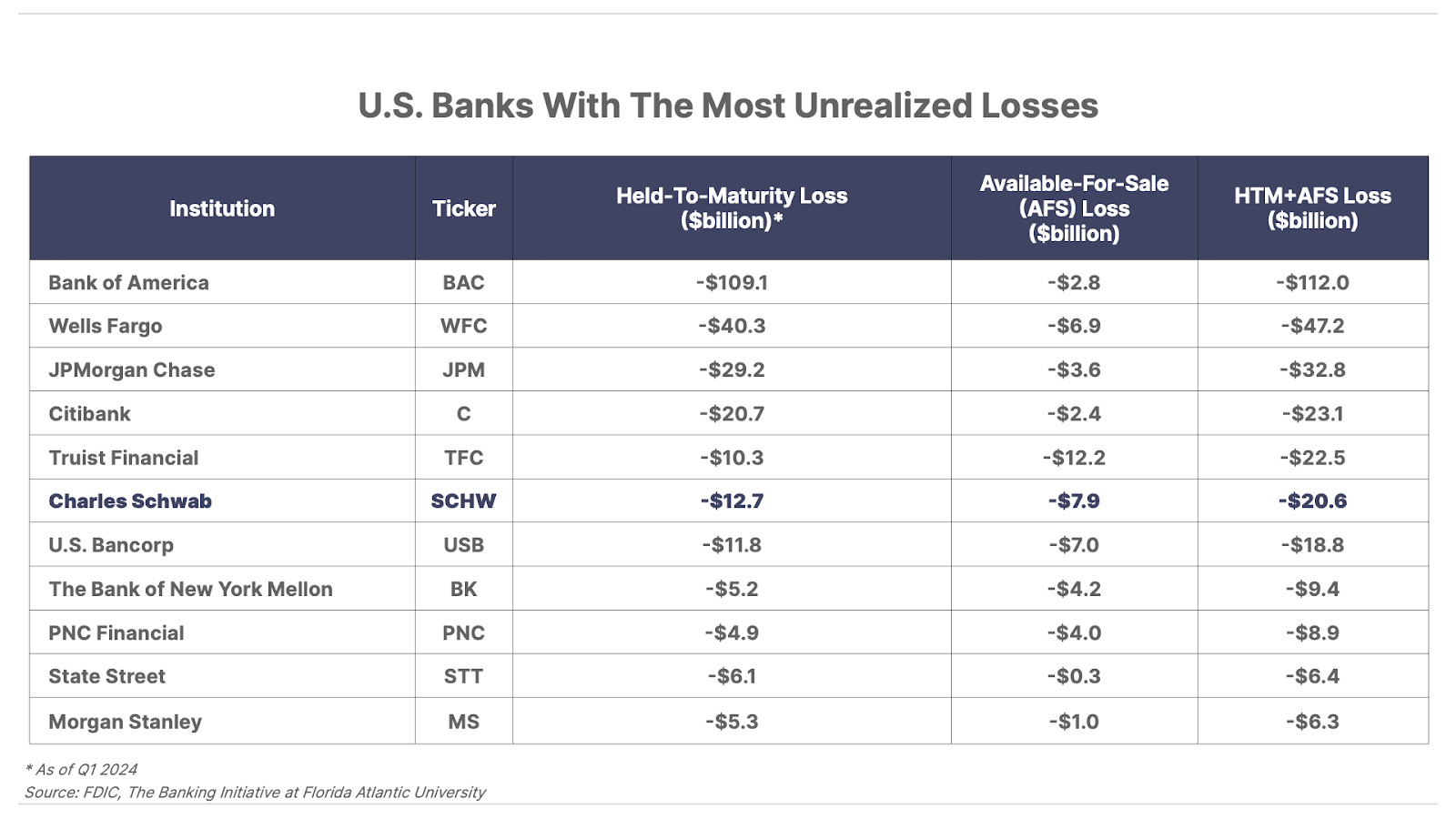

Last October, we highlighted that Bank of America (BAC) had the most unrealized losses of any U.S. bank by far. That remains the case today. However, as you can see below, Schwab isn’t far behind, with unrealized losses that exceed those of all but five of the largest banks in the country.

Yet, even that jaw-dropping figure – showing that Schwab has nearly $21 billion in unrealized losses, between both held-to-maturity and available-for-sale securities – doesn’t tell the whole story. That’s because Schwab is smaller – and holds significantly lower reserves – than most of the banks on this list.

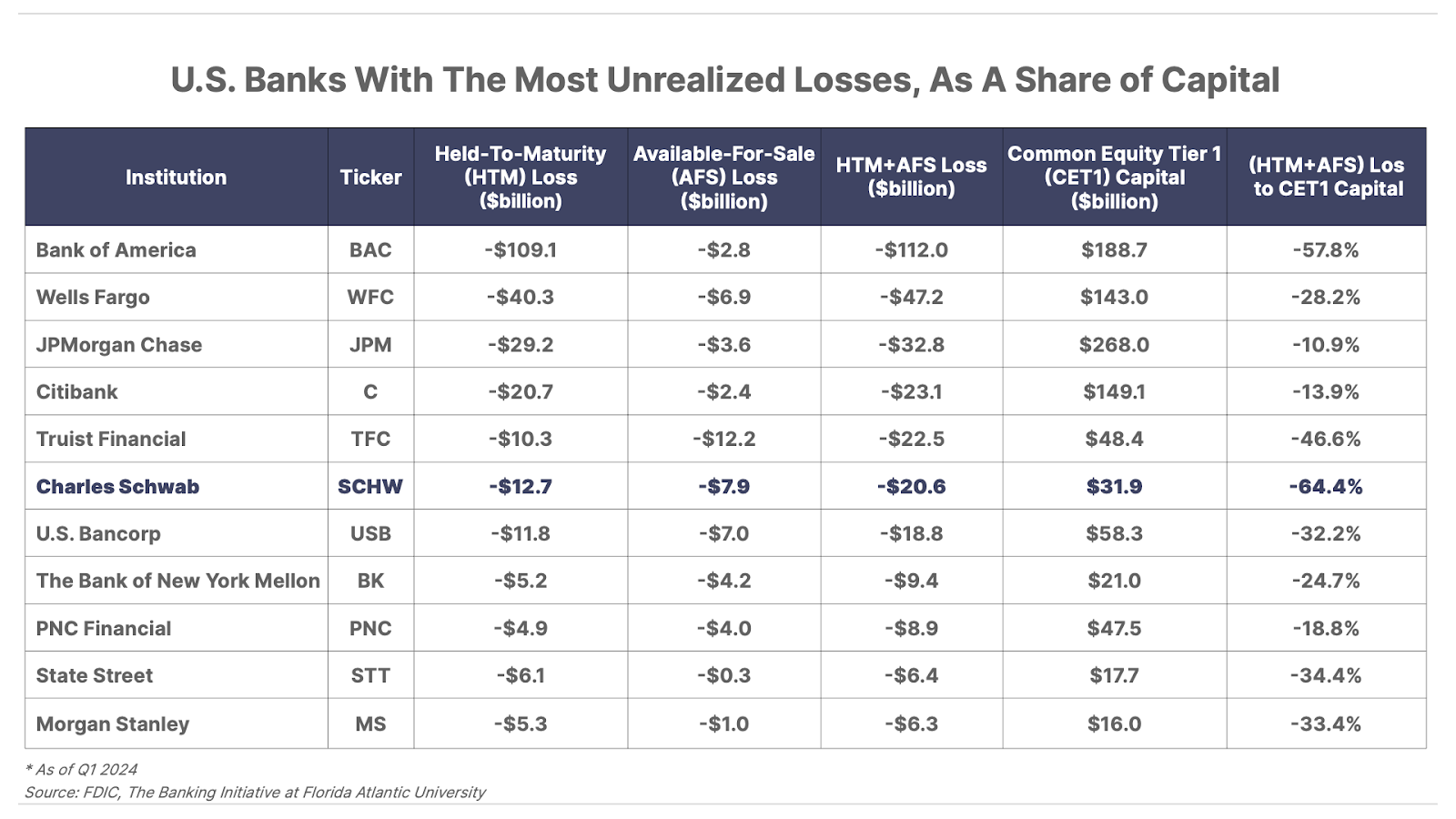

When viewed through this lens, Schwab appears even more fragile.

The company’s unrealized losses exceed 64% of its common equity tier 1 (“CET1”) capital – regulators’ preferred measure of bank capital that includes ordinary shares and retained earnings – and well over 100% of its tangible equity capital, as of the first quarter of 2024.

That’s worse than any bank on this list by a huge margin, including Bank of America.

So if Schwab were forced to realize those losses today – due to deposit flight or another unexpected reason – it could easily become insolvent.

In that case, Schwab shareholders could be wiped out even if the government bails out depositors in full (as we saw with SVB and others in the spring of 2023).

“Talk to Chuck”… But Don’t Own His Stock

To be clear, insolvency is not our expectation here. However, there are still some huge potential risks for Schwab shareholders, even if the company avoids a worst-case scenario.

First, Schwab’s deposit base has been shrinking significantly, as customers move funds from accounts currently paying them just 0.45% to competitors (like Robinhood, which pays up to 5% on cash balances) or Schwab’s own money-market fund (offering more than 5%).

Earlier this month, Schwab reported that bank deposits fell 17% year-over-year in the second quarter, to $252 billion. All told, the company has lost roughly $175 billion in bank deposits since the Fed started raising rates in 2022, a total decline of nearly 40%.

This exodus of customer deposits is far from a true panic-driven bank run. But it is a massive obstacle to the growth and profitability of Schwab’s most important business segment going forward.

Second, there is a significant opportunity cost for holding those underwater assets, even if the losses are never realized. Those bonds represent tens of billions of dollars in idle capital that Schwab can’t deploy elsewhere to earn a higher return and pay out higher yields to slow further deposit flight. This again is likely to be a drag on growth for years.

To be fair, Schwab management did recently announce that it’s exploring plans to offload some of this debt to TD Bank – a Canadian institution and Schwab’s largest shareholder following its recent merger with TD Ameritrade.

If successful, this move would reduce the existential risk of those unrealized losses. However, it would also permanently shrink Schwab’s asset base, and would further weigh on growth. A true Catch-22.

Finally, Schwab’s brokerage business has also been underperforming lately, despite an artificial intelligence-fueled stock market mania and soaring trading volumes.

The company reported new brokerage accounts grew by just 3% year-over-year in the second quarter – and actually declined 10% from the previous quarter. For comparison, privately held competitor Fidelity Investments reported that its brokerage accounts grew by 9% year-over-year in its latest quarter.

When the market mania inevitably ends, brokerage businesses like Schwab’s are likely to experience a dramatic decline in revenue as record trading volumes slow. And though this business only accounts for 17% of Schwab’s total revenue, it could certainly exacerbate the banking issues above.

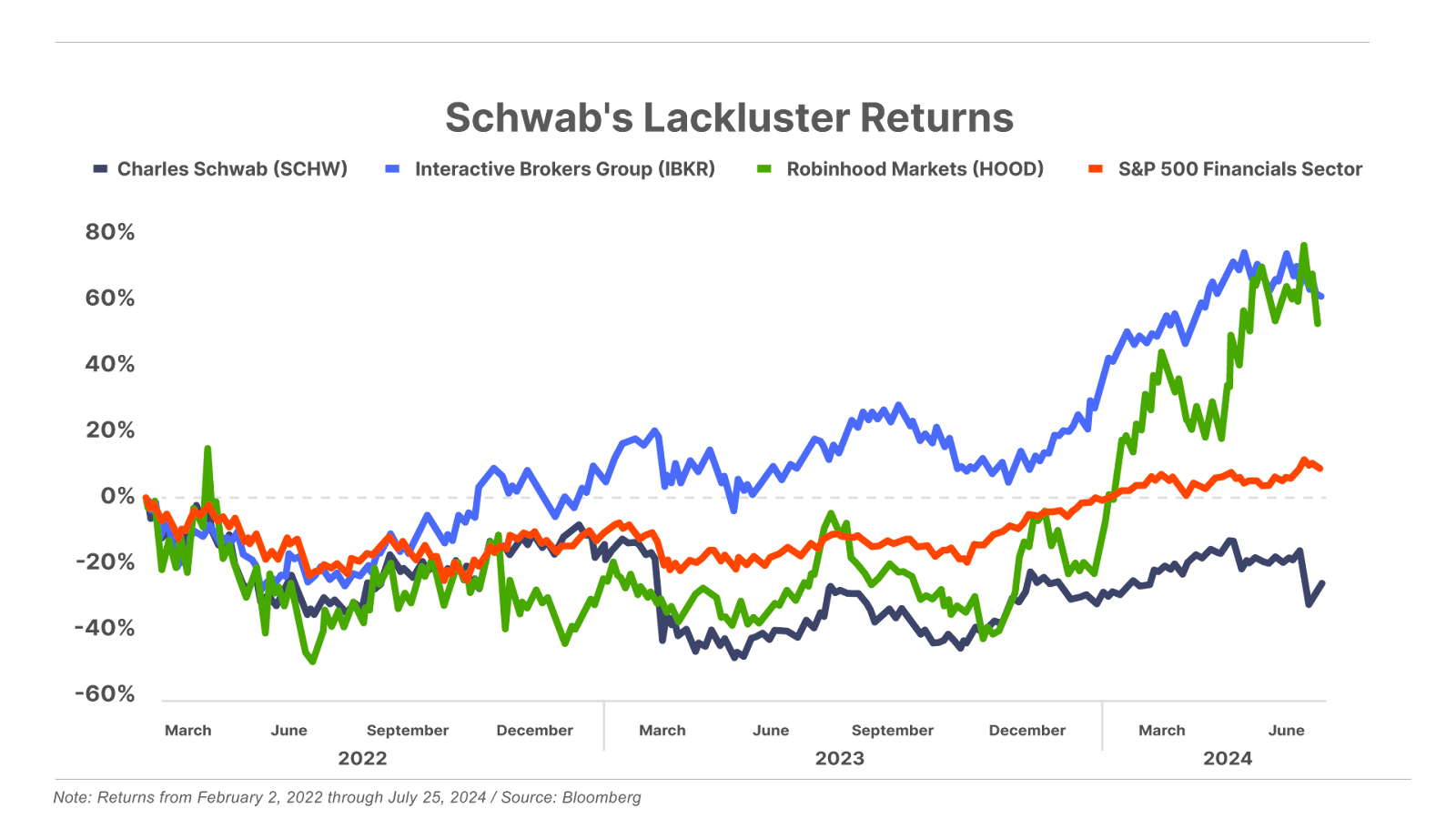

Given these risks, it’s little surprise that Schwab’s stock price has fallen. Shares are trading more than 30% below their pre-banking-crisis peak of just under $100 in early 2022, and have significantly underperformed those of publicly traded competitors and the broad financial sector over that time.

We don’t expect that to change anytime soon, and would recommend that investors avoid owning Schwab shares today.

One final note…

This warning applies specifically to Schwab shareholders, not Schwab customers.

U.S. brokerages are required by law to segregate – or keep separate – client assets from their own, so that those assets can be quickly and easily returned to customers if the brokerage goes out of business.

In addition, the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (“SIPC”) will reimburse investors up to $500,000 per brokerage account (including up to $250,000 for uninvested cash in that account) in the (highly unlikely) event that a brokerage fails and client assets are missing due to fraud or other causes.

Similarly, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”) insures the value of bank deposits up to $250,000 per account.

If your account balances are below these respective limits, there’s generally no reason not to hold your assets at Schwab.

That said, neither the SIPC nor the FDIC have the financial resources to cover all brokerage and bank accounts in the event that several large financial institutions fail simultaneously (and ultimately, they would likely have to be bailed out by the Fed’s money printer as well).

So if you have a large account, are extremely risk averse, or simply ascribe to the age-old wisdom of “don’t keep all your eggs in one basket,” it’s probably not a bad idea to diversify your investment holdings across a handful of brokers and banks.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD