This High-Margin Royalty Company Has Years of Growth Ahead

Profiting Off Land, Oil, and Water in the Desert

| Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at: [email protected]. Paid subscribers can also access this issue as a PDF on the “Issues & Updates” page here. |

The cool winter months are prime building season in steamy Fort Bend County, Texas.

And the Fort Bend School District’s latest construction project, a new career and technical center, was on time and on budget… until February 2018, when the backhoe struck bone.

And more bone.

Some 19,570 bones later – comprising 95 complete human skeletons – the Fort Bend construction project was put on indefinite hold while sensational news reports abounded and the Texas Historical Commission pieced together the full story…

The Fort Bend builders had inadvertently unearthed the nation’s largest mass grave for slaves: 94 African-American men and one woman, who’d been literally worked to death at Sugar Land, once Texas’s largest sugar plantation. The “Sugar Land 95” had harvested sugar cane while chained hand and foot. The chains were buried there, too.

Forensic analysis revealed the victims ranged in age from 14 to 70… and they had all died between 1878 and 1912.

No, that’s not a typo. These Americans died in chains decades after the Union army trounced the Confederates to end the Civil War in 1865… decades after slavery had been “abolished” via the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

And it was all perfectly legal.

Revisionist historians often gloss over this fact, but the legislators who penned the Thirteenth Amendment purposely left in a loophole that allowed slavery to continue under certain circumstances. After all, without the South’s slave-fueled cotton and sugar industries, vast swathes of the U.S. would go bankrupt. (Cotton alone brought in $5 billion yearly in today’s dollars, accounting for over 60% of U.S. exports.)

The carefully worded amendment read: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, nor any place subject to their jurisdiction” (italics added).

In other words, the government just needed a few trumped-up crimes, a few (thousand) extra convictions, and a handy prison-to-sugar-fields pipeline… and slavery lived on, just under a different name.

That name was “convict leasing” – a spectacularly unjust system that used special “Black Laws” to nail African-Americans for “crimes” like flirting with white women, being unemployed, or standing somewhere a white person didn’t want them to. Once the “suspects” (generally, young men in prime working condition) were in jail, the prison would then rent the inmates out to industrial cotton and sugar farms as forced labor.

It was a brutal system, rife with whippings, clubbings, inhumane work conditions, dysentery, and malaria. In Texas alone, an estimated 3,500 leased convicts died between 1866 and 1912, when the program ended – much more than the total number of African-Americans who were lynched in Southern states during the same time period. Most of the inmates at Sugar Land died within two years of arrival.

But the most stunning thing about convict leasing wasn’t its cruelty…

Do As I Say, Not As I Do

Remarkably, the convict-leasing system was championed by the exact people you’d think would abhor it: the “enlightened” abolitionists who’d made the most noise about freedom and equality for slaves… people who, today, would likely identify as bleeding-heart liberals.

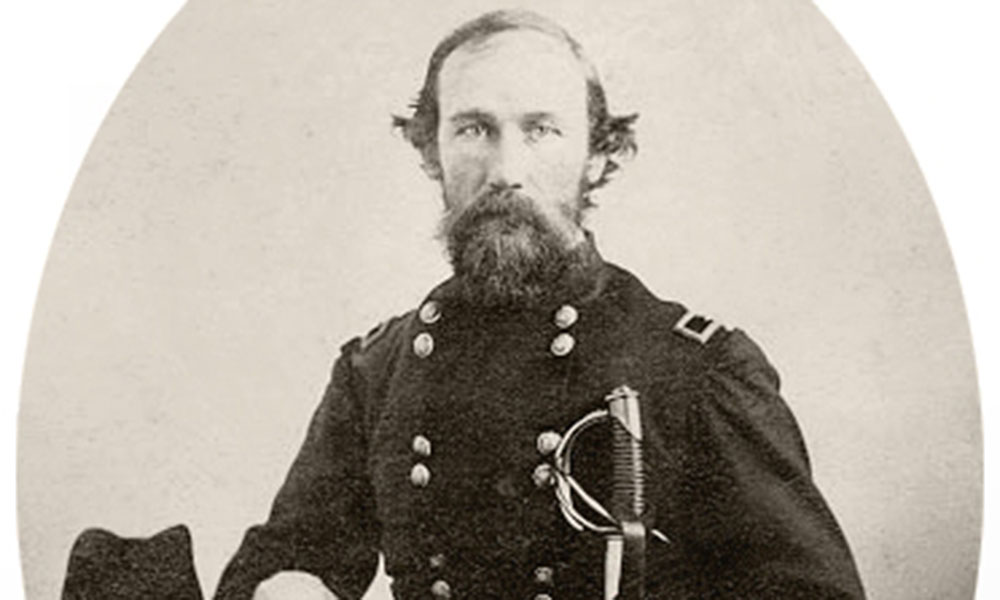

“Pro-black,” pro-abolition Texas Governor Edmund J. Davis (more on him in a moment) was one of these oxymoronic characters. He was a white Southerner who’d been opposed to secession and served as a general in the Union Army – and later, as a Union-friendly “puppet governor” after the South surrendered. His fellow Texans saw him as a sellout and a traitor… but “opportunist” might be the better word.

Publicly, Davis championed full equality and citizenship for freed slaves… but, with far less fanfare, in 1871, he leased the entire Texas prison system to a group of Galveston businessmen who needed cheap labor to build a railroad. Despite reports of serious abuse – and convicts cutting off their own fingers to get out of the system – Governor Davis was happy to let the program continue (and to pad the state budget with lease payments that would amount to millions of dollars today).

Why would an avowed Civil War abolitionist support Slavery 2.0?

As we’ve written before, history often comes in uncomfortable shades of gray. And despite lots of cherished American mythology, the truth is, folks like Edmund J. Davis – and the Northern politicians who wrote in the “slavery for convicts” escape clause – weren’t really that concerned with freeing enslaved Black people. That wasn’t the point of the Civil War. Slavery was a useful talking point to get people riled up… but not the main issue.

The real goal was getting the uppity, too-independent Southern states back in line and making sure they didn’t disobey orders from the “Big House” – the federal government.

When the North won the war, big government officially trumped states’ rights – and in many cases created a dystopian hellscape that was a lot worse than before. (It also laid the groundwork for plenty of other “hidden” forms of slavery in decades to come. For-profit prisons spring to mind. So does the welfare state.)

That overbearing central government handed Texas its infamous “woke” constitution in 1869… setting in motion a seven-year-long disaster that ended with the state capitol door getting smashed in with an axe.

That fiasco also spawned one of the most lucrative land-royalty companies of all time… but that came later…

Where Have All The Cowboys Gone?

Once the South surrendered, Reconstruction, the painful years of post-conflict rebuilding, began. Naturally, it happened on terms determined by the (winning) U.S. government.

Those terms were stern. President Andrew Johnson appointed a temporary governor for each former Confederate state until the states agreed to the Thirteenth Amendment. Once they’d updated their laws (and proven their loyalty to Washington, D.C.’s satisfaction), they’d be allowed to rejoin the Union.

If you’ve ever met anyone from Texas, you can already imagine how well this went…

Texans aren’t fond of being told what to do (remember the Alamo?), and they point-blank refused to ratify the amendment. So in June 1865 – two months after the end of the Civil War – the U.S. government sent 2,000 federal troops down to occupy Texas until the stubborn cowboys came to their senses.

Along with the military presence came the unwelcome person of “traitor” Edmund J. Davis. The federal military held a special “election” in 1869 installing Davis as governor, ginned up a kangaroo constitutional convention, and helped Davis draw up a new, government-approved Texas constitution.

It included the Thirteenth Amendment… and it took away pretty much everything that made Texas, Texas.

Some of the features of this constitution wouldn’t look out of place in ultra-liberal Democrat legislation today. States’ rights were downplayed in favor of sweeping federal control. Citizens were taxed heavily to contribute to a public-school fund. They were also taxed to pay for a Bureau of Immigration, which would bring in foreigners and settle them within the state. (Just imagine seeing that on the ballot at your next state election…)

Crucially, the constitution forbade Texas from using state funds to support private enterprise like railroads – that would just encourage too much independence altogether.

But the constitution did one thing right: It got the government off Texas’ back. With the Thirteenth Amendment finally enshrined in state law, Washington withdrew troops from Texas in 1870 and welcomed the Lone Star State back into the union.

First item on the new state’s agenda: vote the hated Davis out in a landslide. (He didn’t take kindly to the rejection and, as protest, locked his keys in his former office in the state capitol – that’s when the door got smashed with the axe.)

Next up: a brand-new constitution, which was ratified in 1876. It’s a limited-government, “don’t mess-with-Texas” piece of legislature that’s still in place today, with some minor modifications.

While the Thirteenth Amendment (and its regrettable convict clause) remained intact, most of the other nonsense got slashed. One centerpiece of the new constitution was the right to use state funds to improve infrastructure within the state..

Notably, for the first time in state history, it codified “land grants” into law. The constitution allowed the government to offer large parcels of free land as incentives to private railroads to bring their business to the Lone Star State.

It was those “great big tracts of land” that enticed robber baron and railroad magnate Jay Gould to Texas in 1880.

Sensing opportunity in the new, railroad-friendly constitution, real-estate-hungry Gould routed several of his train lines through the state in exchange for 16 prime parcels of land per each mile of track he put down.

And many years later, the acres Gould scored as part of that railroad deal would create the capital efficient land royalty company we’re recommending in this issue.

Since then, this business has become one of the longest-running success stories in the American stock market. An initial investment of $3,000 at its formation in the late 1800s would have grown into $2 billion today. And despite its incredible track record of wealth creation, few investors have ever heard of it.

This obscure security has no coverage from Wall Street analysts, for one simple reason: it doesn’t need to hire big banks to raise new capital. That’s because this incredibly capital efficient business generates all the cash it will ever need, with plenty left over for consistent dividend payouts and share repurchases. In fact, due to its unusual structure, it was originally formed with the sole objective of returning capital to investors.

From Busted Railroad to America’s Richest Landlord

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care Concierge, Lance James, at 888-610-8895.