The rise in interest rates has ended the cheap money era, helping restore a more rational allocation of capital in the energy sector. And one company is best positioned to win in this new era of Shale 2.0.

Less Gas, More Cash

A “Forever Commodity Stock” with 17% Free Cash Flow Yield

Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email your personal concierge, Lance, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected]. At the end of this issue, you’ll find our model portfolio, watchlist (which is also here), and Mailbag — as well as a “Best Buys” section, where we’ll briefly cover three portfolio names that we think you should consider buying first. Again… we’re excited that you’re with us…and we’re looking forward to a long and fulfilling relationship. If you’re not a member and would like to learn more, click here. |

The coroner could only identify him by his teeth.

The Chevrolet Tahoe had slammed into a concrete overpass in Oklahoma City at 88 miles an hour… and the driver’s body was charred beyond recognition. But the corpse’s pearly whites were miraculously intact. Two days after the fiery crash in March 2016, a forensic odontologist dug through dental records to come up with a name: Aubrey McClendon.

To many Oklahomans – and others – the name sparked a double take. Wait, what… that Aubrey McClendon? The civic-minded oil baron who donated generously to local charities… was inducted into the Oklahoma Heritage Foundation’s Hall of Fame… was a wine connoisseur with a 100,000-bottle collection… and owned 20% of the NBA’s Oklahoma City Thunder franchise?

And also… the Aubrey McClendon who’d just been indicted for conspiracy by a federal grand jury?

Yep, that guy. All of the above.

The 56-year-old McClendon – who’d made a multibillion-dollar fortune in the Texas and Oklahoma oil fields during the early-2000s shale boom – had privately been unraveling for quite some time…

The company he co-founded in 1989, Chesapeake Energy, was an early pioneer of the hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling techniques that launched the shale revolution. By 2005, Chesapeake was the second-largest natural gas producer in America, after ExxonMobil.

The success of Chesapeake earned McClendon a spot on the Forbes billionaire list that year. And then he got greedy: He started using Chesapeake’s oil wells as a personal piggy bank.

He awarded cushy board positions to his close friends – who, in turn, voted to pay him the highest salary of any S&P 500 CEO: $112 million. He and his family flew around in company-owned private jets, funneled millions of dollars of catering for Chesapeake corporate events to a McClendon-owned restaurant franchise, and commandeered an entire division of Chesapeake to work on the family’s personal home renovations.

And when McClendon needed a little extra spending money, he convinced his compliant board to buy his antique-map collection for $12 million.

Even more concerning, a 2012 Reuters exposé revealed that he’d “operated a secretive, $200 million hedge fund from inside Chesapeake’s offices, and received as much as $1.4 billion in loans against his well interests.”

McClendon’s self-dealing was so flagrant that even his hand-picked board couldn’t overlook it. After the Reuters story came to light, the directors removed McClendon as chairman. (He stayed on as CEO for another year before resigning to start a new company, American Energy Partners.)

And then there was the conspiracy…

During the heyday of his Chesapeake years – around 2007, with the company’s market valuation headed to all-time highs of $38 billion – McClendon reportedly colluded with other large oil and gas companies to keep Oklahoma land prices low… giving a new meaning to the term “oil rig”.

One of the biggest problems with the shale boom was the flood of capital that bid up drillable acreage to unsustainable prices. High land costs meant shale economics could never work – companies wouldn’t make enough money from drilling to offset the price of the real estate.

McClendon – eager to stay on the billionaire list – had a devilishly ingenious solution: artificially suppress the prices landowners could get at auctions during the peak boom period.

His method was simple: email his old buddy Tom Ward, the head of “rival” company SandRidge Energy. McClendon suggested that the two of them decide in advance who would win land auctions, and then the “winner” would parcel out an interest in the land to the “loser.” He also emailed other companies suggesting similar deals, with comments like, “Should we throw in 50/50 together here rather than trying to bash each other’s brains out on lease buying?”

A few years later, those emails would come back to frack things up for Aubrey McClendon.

Before then, though, the market did him in. An oil and gas glut sent prices sharply lower in 2014… and Aubrey’s billion-dollar net worth was cut in half in a matter of months. His former company, Chesapeake Energy, which had racked up a $20 billion debt load under his leadership, saw its valuation plummet from a peak of $38 billion to less than $3 billion.

His next project, American Energy Partners, started hemorrhaging money, too. As big investors backed away from the privately-traded company, McClendon tapped into personal investments and called in favors to keep the company afloat. He even put up as collateral – and lost – the oil wells he’d retained as a legacy interest when leaving Chesapeake.

And in March 2016 – after a four-year investigation sparked by the 2012 Reuters piece – the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) was ready to pounce.

The DOJ alleged that McClendon’s bid-rigging antics had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act, a piece of 1890s legislation designed to break up unfair monopolies. “Executives who abuse their positions as leaders of major corporations to organize criminal activity must be held accountable for their actions,” the Assistant Attorney General said in a statement announcing McClendon’s March 2016 criminal indictment.

There was no friendly board to help him out of this one. The DOJ was pushing for hard time – up to 10 years.

So McClendon skipped a private dinner at Oklahoma City’s ritzy Beacon Club… and disappeared in his silver Chevy Tahoe.

And a few days later, his only identifying feature was his teeth.

Aubrey McClendon’s final hours remain a mystery. The autopsy showed that he’d taken the sedative drug Doxylamine and steered his SUV onto the highway at 9 am, the day after his indictment – without his seatbelt fastened. An Oklahoma City Police spokesman reported, “He pretty much drove straight into the wall… There was plenty of opportunity for him to correct and get back on the roadway, and that didn’t occur.”

The medical examiner ruled the death an accident, but it’s not clear what really happened. We may never know if a drugged McClendon fell asleep at the wheel, took his eyes off the road… or drove into that wall on purpose.

It was an unsettling end to a life Reuters called “lavish and leveraged.”

And it summed up everything that went wrong for investors during America’s wild, debt-fueled shale boom.

Energy’s Lost Decade

The decades-long shale boom established U.S. energy independence, pushed down prices for hundreds of millions of energy consumers, and was an economic boon to huge swathes of America.

But despite these benefits for society at large, shale was an unmitigated disaster for investors. It turned energy from one of the best-performing sectors in the stock market to its worst.

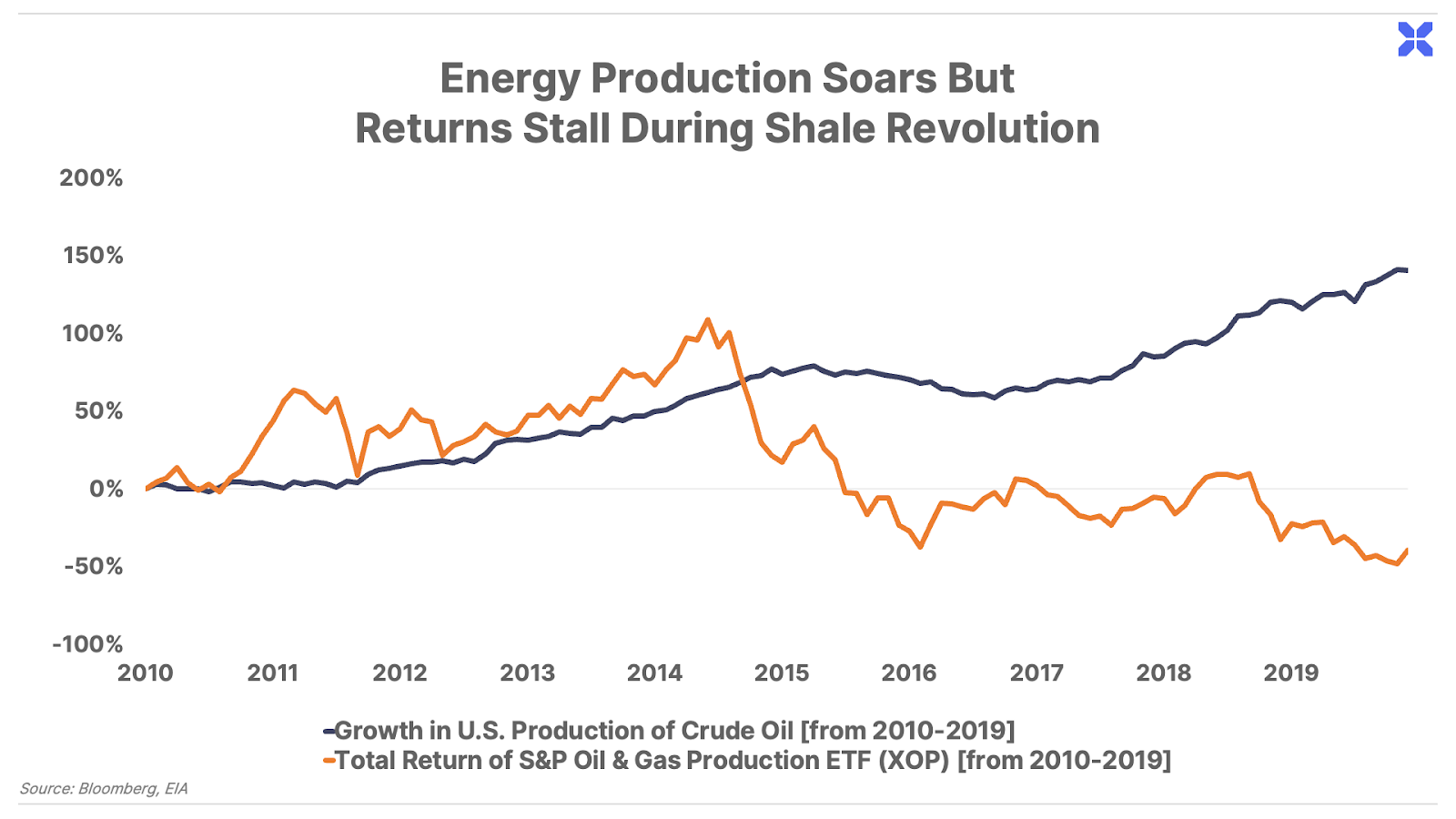

From 2010 to 2019, U.S.-listed energy stocks overall suffered their first “lost decade” in history, falling by 35%, even as U.S. energy production soared to record highs:

During the boom, shale CEOs touted their advancement of new fracking technologies and horizontal drilling. On the surface, the blockbuster production results of new shale wells blew away their conventional well counterparts – with the hope of generating future cash flow. But most of these prolific new shale wells never led to profits for investors. In reality, the production gains of the shale revolution came from pouring more money into the ground – and not getting enough back out. As the Wall Street Journal explained in 2018:

“Shale companies’ profitability may also be threatened by rising costs for the immense amounts of sand and water needed for fracking. Modern fracking jobs now require 500 tons of steel pipe, enough water to fill 35 Olympic swimming pools, and enough rail cars filled with sand to stretch for 14 football fields, according to Rice University’s Center for Energy Studies.”

And while overzealous CEOs like Aubrey McClendon deserve much of the blame, corporate greed didn’t suddenly spring to life in the energy sector over the last decade. The new feature that did appear was the zero percent interest rate policy (“ZIRP”) from the U.S. Federal Reserve.

More than anything else, cheap money fueled the shale revolution.

The ZIRP era of the last decade allowed shale drillers to raise hundreds of billions in cheap capital. Investors could no longer earn a safe yield from traditional fixed-income investments. The shale sector provided an outlet for billions of investor capital searching for a hot new growth sector. The flood of cheap money allowed companies like Chesapeake to raise new debt to plug the shortfalls in their cash flow statements.

Shale drillers were given a greenlight to bid up the costs of land, labor, and drilling equipment in the ravenous pursuit of production growth. Cheap money papered over the supply-and-demand balancing act that would have otherwise kept the sector in check. Even when prices collapsed from oversupply, the industry continued spending with reckless abandon.

From 2014 to 2016, excess shale production oversupplied the market and sent oil and gas prices to multi-decade lows. Normally, this kind of price collapse would have caused a sharp pullback in capital spending. But the ZIRP era kept cheap money flowing, and the shale boom continued.

Consider the price of land in the Permian’s Delaware shale oil basin from 2014 to 2016. Despite oil prices dropping from over $100 per barrel to less than $30, shale drillers bid up land prices from $3,000 per acre to as high as $48,000 per acre

After a blip down in production from 2015 to 2016, shale producers went on to post record highs in production in 2017… followed by a record 30% growth in the two-year stretch from 2018 to 2019. Eventually, the combination of soaring input costs and depressed prices wreaked havoc on the sector’s financial performance.

As the calendar turned on the first decade of the shale revolution, a record amount of capital had been destroyed in the energy sector. One study from consultancy firm Deloitte summarized the dismal outcome for energy investors over those 10 years:

“The U.S. shale industry registered net negative free cash flows of $300 billion, impaired more than $450 billion of invested capital, and saw more than 190 bankruptcies since 2010.”

It was one of the few cases where the Federal Reserve’s cheap-money policies stole from the rich and gave to the poor. The losses sustained by shale investors provided a decade-long subsidy of artificially cheap energy for American consumers.

But now, that’s all changed.

The Rise of Shale 2.0

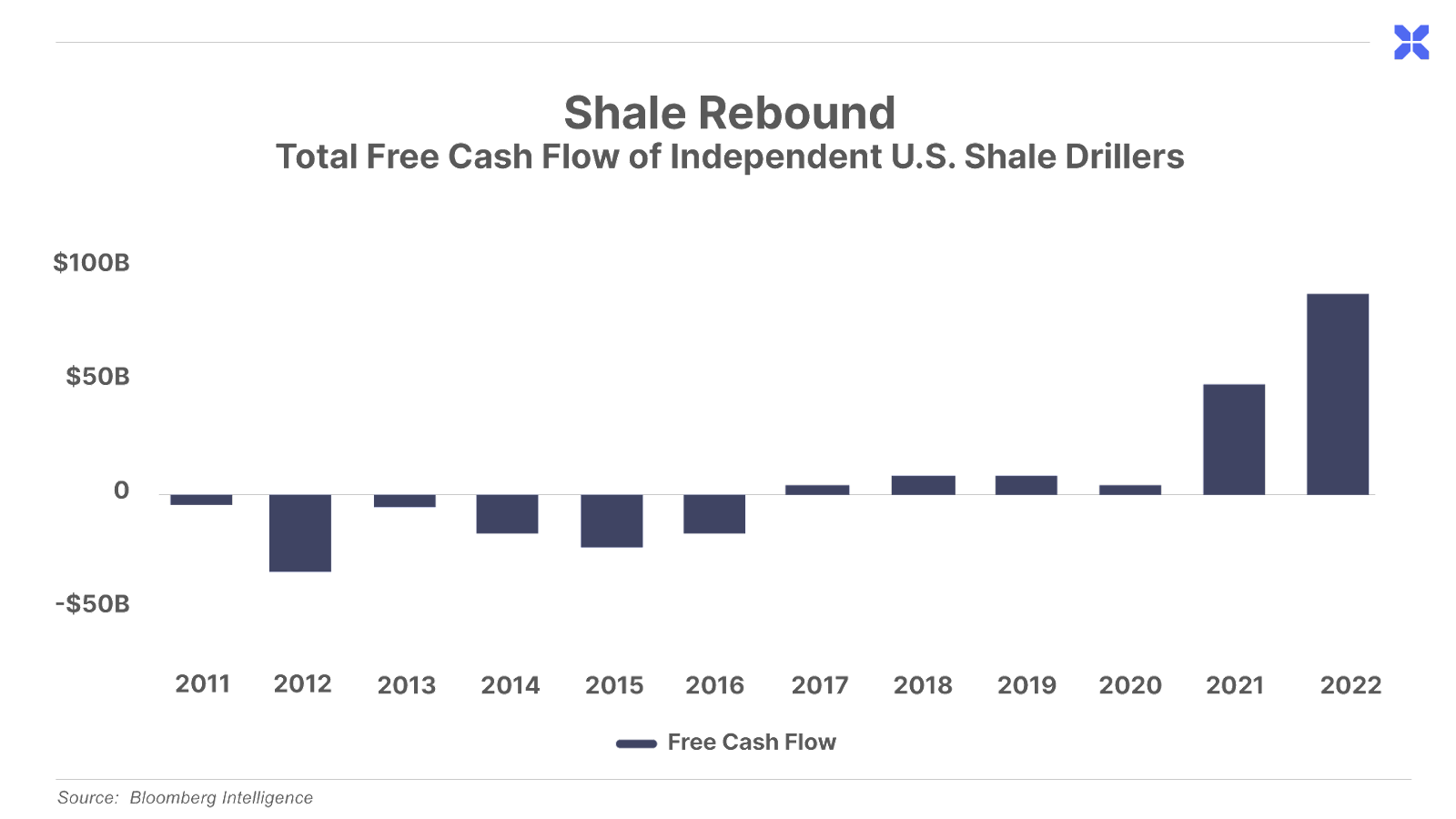

The rise in interest rates has ended the cheap money era, helping restore a more rational allocation of capital in the energy sector. And today’s energy investors have demanded an end to the previous regime of profitless production growth. This has unleashed the new era of Shale 2.0, where capital discipline and shareholder returns have become paramount. Investors are reaping the benefits, as the shale industry has begun to record positive free cash flows in recent years:

This renewed focus on capital discipline has provided an uplift for energy companies across the board. But one company is best positioned to win in this new era of Shale 2.0.

The company is led by the man who literally wrote the book on capital allocation – William Thorndike Jr., author of The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success.

We previously wrote about one of the Outsiders that Thorndike profiles in his book – John Malone, America’s greatest CEO. These Outsiders came from a range of industries, but they all shared a laser focus on capital allocation to drive world-class shareholder returns during their tenure.

Well ahead of the rest of the gas industry, Thorndike applied the Outsider playbook to America’s shale patch. Over the last three years, the company Thorndike oversees has become one of the industry’s most consistent cash generators.

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care Concierge, Lance James, at 888-610-8895.