Total War Is Coming Soon, and It Will Transform Society

Sequel to the Classic That Predicted the 2008 Crash

Editor’s Note: For the month of August, we’re producing a special series called “What We’re Reading.”

Each Friday, members of the Porter & Co. team are sharing an excerpt from their personal summer reading – books that they found instructive, or ones that they just plain enjoyed. We hope you’ll like them too.

Last week, Big Secret on Wall Street analyst Ross Hendricks offered up a portion of Common Stock and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings, an investing classic by Philip A. Fisher… whose work directly inspired Warren Buffett’s investment strategy.

This week, Investment Chronicles editor Justin Brill is presenting to readers the first chapter of The Fourth Turning Is Here, Neil Howe’s followup to his 1997 cult favorite The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy. An analysis of generation-driven historical cycles, the first book predicted that a period of political and economic upheaval would rattle the U.S. midway through the first decade of the 2000s. In this new book, Howe says, serious change is coming soon to society – then he provides cause for cautious optimism.

Justin leads off the book selection with a brief introduction about Howe’s profound message.

If you’re like many readers – particularly those in the U.S. and Europe – you may feel as though the world and social order are falling apart.

Many governments have become bloated, detached bureaucracies that no longer serve the public. Once highly-respected companies are failing, having become shells of their former selves. Nationalism and shared values have given way to populism and extreme partisanship. Meaningful, lifelong careers have been pushed aside for “gig economy” jobs. The cost of everything is soaring. So-called “deaths of despair” – those due to suicide or drug and alcohol abuse – are rising even faster.

Yet, as the work of historian, economist, and demographer Neil Howe (and his late colleague William Strauss) has highlighted, we are not the first society to experience this kind of upheaval, and we won’t be the last.

Modern history has followed a remarkably predictable cyclical pattern. In short, each full cycle – or “saeculum,” as Howe calls them – spans the length of a long human life (roughly 80 to 100 years). Each saeculum is divided into four seasons (what Howe calls “turnings”) that span one generation (20 to 25 years). And each saeculum ends with a crisis period (a “Fourth Turning”) that sees the current social order break down and a new one take its place.

Howe believes we are now well into the latest Fourth Turning, which will culminate in an existential crisis within the next 10 years… and, by the time it ends, it will have dramatically reshaped the world as we know it.

In the chapter below from his book, the Fourth Turning Is Here, Howe explains how previous turnings have shaped history… highlights the remarkable similarities between the current Fourth Turning and those of the past… and most importantly, shares what we should expect as this crisis era reaches its climax in the years ahead. – Justin Brill

The Seasons of History

The reward of the historian is to locate patterns that recur over time and to discover the natural rhythms of social experience.

At the core of modern history lies this remarkable pattern: Over the past five or six centuries, Anglo-American society has entered a new era – a new turning – every two decades or so. At the start of each turning, people change how they feel about themselves, the culture, the nation, and the future. Turnings come in cycles of four. Each cycle spans the length of a long human life, roughly 80 to 100 years, a unit of time the ancients called the saeculum. Together the four turnings of the saeculum comprise history’s periodic rhythm. in which the seasons of spring, summer, fall. and winter correspond to eras of rebirth, growth, entropy, and (finally) creative destruction:

- The First Turning is a High, an upbeat era of strengthening institutions and weakening individualism, when a new civic order implants and an old values regime decays.

- The Second Turning is an Awakening, a passionate era of spiritual upheaval when the civic order comes under attack from a new values regime.

- The Third Turning is an Unraveling, a downcast era of strengthening individualism and weakening institutions, when the old civic order decays and the new values regime implants.

- The Fourth Turning is a Crisis, a decisive era of secular upheaval, when the values regime propels the replacement of the old civic order with a new one.

Each turning comes with its own identifiable mood, Always these mood shifts catch people by surprise.

In the current saeculum, the First Turning was the American high of the Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy presidencies. As World War II wound down, no one predicted that America would become so confident and so institutionally muscular, yet also so bland and socially conformist.

But that’s what happened.

The Second Turning was the Consciousness Revolution, stretching from the campus revolts of the mid-1960s to the tax revolts of the early 1980s. In the months following John Kennedy’s assassination, no one predicted America was about to enter an era of personal liberation and cross a cultural watershed that would separate anything thought or said afterward from anything thought or said before. But that’s what happened.

The Third Turning was the Culture Wars, an era that began with Reagan’s upbeat “Morning in America” campaign in 1984, climaxed with the dot-com bubble, and ground to exhaustion with post-9/11 wars in the Mideast amid the passionate early debates over “the Reagan Revolution.” No one predicted that the nation was entering an era of celebrity circuses, raucous culture wars, and civic drift. But that’s what happened.

The Fourth Turning – for now, let’s call it the Millennial Crisis – began with the global market crash of 2008 and has thus far witnessed a shrinking middle class, the MAGA rise of Donald Trump, a global pandemic, and new fears of a great-power war. Early in Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign against John McCain, no one could have predicted that America was about to enter an era of bleak pessimism, authoritarian populism, and fanatical partisanship. But that’s what happened.

And this era still has roughly another decade to run.

Propelling this cycle are social generations of roughly the same length as a turning, which are both shaped by these turnings in their youth and later shape these turnings as midlife leaders and parents. Ordinarily, each turning is associated with the coming of age (from childhood into adulthood) of a distinct generational archetype. Thus there are four generational archetypes, just as there are four turnings:

- A Prophet generation (example: Boomers, born 1945-1960) grows up as increasingly indulged post-Crisis children, comes of age as defiant young crusaders during an Awakening, cultivates principle as moralistic midlifers, and ages into the detached, missionary elders presiding over the next Crisis.

- A Nomad generation (example: Gen X, born 1961-1981) grows up as underprotected children during an Awakening, comes of age as the alienated young adults of a post Awakening: world, mellows into pragmatic midlife leaders during a Crisis, and ages into tough post-Crisis elders.

- A Hero generation (example: G.I.s, born 1901-1924, or Millennials, born 1982-2005) grows up as increasingly protected post-Awakening children, comes of age as team-working young achievers during a Crisis, demonstrates hubris as confident midlifers, and ages into the engaged, powerful elders presiding over the next Awakening.

- An Artist generation (example: Silent, born 1925-1942, or Homelanders, often called Gen Z by today’s media, born, 2006-2029) grows up as overprotected children during a Crisis, comes of age as the sensitive young adults of a post-Crisis world, breaks free as indecisive midlife leaders during an Awakening, and ages into empathic post-Awakening elders.

Each turning is therefore associated with a similar constellation of generations in each phase of life. (In an Unraveling, for example, the Artist is always entering elderhood and the Nomad is always coming of age into adulthood.) During each turning, most people pay special attention to the new generation coming of age – because they sense that this youthful archetype, alive to the future’s potential, may prefigure the emerging mood of the new turning.

They’re right. This rising generation does prefigure the emerging mood. Yet like the mood of the turning, the personality of the rising generation always catches most people by surprise.

By the time of the 1945 VE and VJ Day parades, at the start of the First Turning or High, Americans had grown accustomed to massive ranks of organized youth mobilizing to vote for the New Deal, build dams and harbors, and conquer half the world. No one expected a new generation of polite cautionaries who preferred to “work within the system” rather than change it. But with the Silent Generation, that’s what they got.

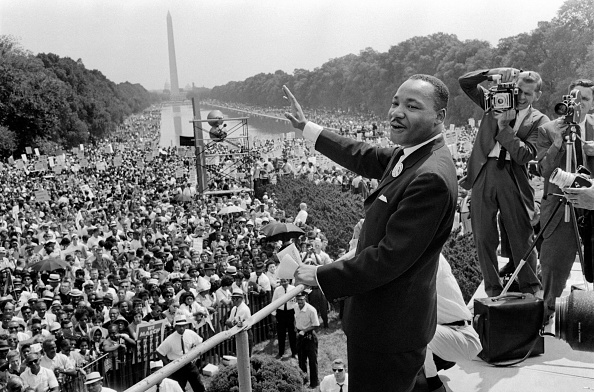

When Martin Luther King. Jr. led his march on Washington, D.C., at the start of the Awakening, Americans had grown accustomed to well-socialized youth who listened to doo-wop music, showed up for draft calls, and worked earnestly yet peaceably for causes like civil rights. No one expected a new generation of rule-breakers who preferred to act out their passions, cripple “the Establishment,” and reinvent the culture. But with the Boom Generation, that’s what they got.

A year after The Big Chill appeared, when Apple was loudly proclaiming that “1984 won’t be like 1984,” Americans at the start of the Unraveling had grown accustomed to moralizing youth who busily quested after deeper values and a meaningful inner life. No one expected a new generation of hardscrabble free agents who scorned yuppie pretension and hungered after the material bottom line. But with Generation X, that’s what they got.

Flash forward 20 years to the peak year of the Survivor TV series, near the onset of the Great Recession and the beginning of the Millennial Crisis. Americans by now had grown accustomed to edgy and self-reliant youth who enjoyed taking personal risks and sorting themselves into winners and lasers. No one expected a new generation of normcore team players aspiring to build security, connection, and community. But with the Millennial Generation, that’s what they got – or perhaps, we should say, are getting.

It’s All Happened Before

So much for the shifts in national mood and generational alignment over the last saeculum, stretching back to the end of World War II. Have shifts like these ever happened before in earlier saecula? Yes, many times.

Let’s first conjure up America’s mood near the close of the most recent Third Turning or fall season: the Culture Wars. Most readers will be old enough to recall personally much of what happened between the end of the Cold War (1991) and the Great Financial Crisis (2008). They may have fond memories of that era’s new sense of personal freedom and diversity, less fettered either by laws or regulation (“The era of big government is over,” declared President Clinton in 1996) or by scolding prudes (“Just Do It” was Nike’s iconic slogan of the 1990s). They may have more anxious memories of that era’s wilder and meaner trends, such as terrifying rates of violent crime, a darkening pop culture (unless Public Enemy and Nirvana remain at the top of your oldies list), and the rapid erosion of unions and public programs that once protected the middle class.

At the cutting edge of it all was an undersocialized rising generation whose favorite new motto (“works for me”) celebrated a self-oriented pragmatism and whose favorite generational non-label (“X”) was meant to deflect the canting moralism of former hippies hitting midlife. Meanwhile, adults of all ages did their best to shelter a new generation of “babies on board” who were now aging into grade-schoolers located in carefully marked “safe” zones.

As highlighted by such best-selling authors as John Naisbitt (Megatrends) and Alvin Toffler (Powershift), our world in that era was becoming more complex, diverse, decentralized, high-tech, and self-directed. It was a freer, coarser, less governed America in which no one really took charge of any big issue from globalization and deficits to poverty-level wages and haphazard wars. Most Americans went along with the open-ended mood and voted for the leaders who provided it. Only a minority mounted a fierce resistance and denounced those whom they held responsible. But, as time went on, it’s fair to say that most Americans had serious misgivings about where a leaderless nation would eventually find itself.

If we want to find a historical parallel, we need to go back roughly one long lifetime (80 to 100 years) before the end of this Third Turning to the end of the last Third Turning.

Elders in their 80s in the early 2000s could have recalled, as children, the years between Armistice Day (in 1918) and the Great Crash of 1929. Euphoria over a global military triumph was painfully short-lived. Earlier optimism about a progressive future succumbed to jazz-age nihilism and a pervasive cynicism about high ideals. Bosses swaggered in immigrant ghettos, the KKK in the Heartland, the Mafia in the big cities, and defenders of Americanism in every Middletown. Unions atrophied, government weakened, voter participation fell, and a dynamic marketplace ushered in new consumer technologies (autos, radios, phones, jukeboxes, vending machines) that made life feel newly complicated and frenetic.

“It’s up to you” was the new self-help mantra of a rising “Lost Generation” of barnstormers and rumrunners. Their risky pleasures, which prompted journalists to announce it was “Sex O’Clock in America,” shocked middle-aged decency brigades – many of them “tired radicals” who were by then moralizing against the detritus of the “mauve” decade of their own youth (in the 1890s), During the Roaring Twenties, opinions polarized around no-compromise cultural issues like alcohol, drugs, sex, immigration, and family life. Meanwhile, parents strove to protect a Scout-like new generation of children (who, in time, would serve in World War II and be called the “Greatest Generation”).

Sound familiar?

Let’s move backward another long lifetime (80 to 90 years) to the end of the prior Third Turning.

Elders in their 80s in the 1920s could easily have recalled, as children, the late 1840s and 1850s, when America was drifting into a rowdy new era of dynamism, opportunism, violence – and civic stalemate. The popular Mexican War had just ended in a stirring triumph, but the huzzahs over territorial gain didn’t last long. Immigration surged into swelling cities, triggering urban crime waves, and driving voters toward nativist political parties.

Financial speculation boomed, and new technologies like railroads, telegraph, and steam-driven factories – plus a burgeoning demand for cotton exports – kindled a nationwide worship of the “almighty dollar.” First among the votaries was a brazen young “Gilded Generation” who shunned colleges in favor of hustling west with six-shooters to pan for gold in towns fabled for casual murder. “Root, hog, or die” was the new youth motto.

Unable to contain this restless energy, the two major parties (Whips and Democrats) were slowly disintegrating. A righteous debate over slavery’s territorial expansion erupted between so-called Southrons and abolitionists – many of them middle-aged spiritualists who, in the more utopian 1830s and early ’40, had dabbled in moral reform, born-again spiritualism, utopian communes, and other youth-fired crusades. An emerging generation of children, meanwhile, were being raised under a strict regimentation that startled European visitors who just a decade earlier had bemoaned the wildness of American kids.

Sound familiar?

Run the clock back the length of yet another long life, to the 1760s. The recent favorable conclusion to the French and Indian War had brought a century of conflict to a close and secured the colonial frontier. Yet when Britain tried to recoup war expenses through mild taxation and limits on westward expansion, the colonies seethed with directionless discontent. Immigration from the Old World, migration across the Appalachians, and colonial trade arguments all rose sharply. As debtors’ prisons bulged, middle-aged people complained about what Benjamin Franklin called the “white savagery” of youth. Aging orators (many of whom were once fiery young preachers during the circa-1740 Great Awakening) awakened civic consciousness and organized popular crusades of economic austerity. The children became the first to attend well-supervised church schools in the colonies rather than academies in corrupt Albion. Gradually, colonists began separating into mutually loathing camps, one defending and the other attacking the Crown.

Sound familiar again?

As they approached the close of each of these prior Third Turning eras, Americans celebrated a self-seeking ethos of laissez-faire “individualism” (a word first popularized in the 1840s), yet also fretted over social fragmentation, distrust of authority, and economic and technological change that seemed to be accelerating beyond society’s ability to control it.

During each of these eras, Americans had recently triumphed over a long-standing global threat – Imperial Germany, Imperial New Spain (alias Mexico), or Imperial New France. Yet these victories came to be associated with a worn-out definition of national direction – and, perversely, stripped people of what common civic purpose they had left. Much like the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, early in our most recent Third Turning, they all unleashed a mood of foreboding.

During each of these eras, truculent moralism darkened the debate about the country’s future. Culture wars raged; the language of political discourse coarsened; nativist feelings hardened; crime, immigration, and substance abuse came under growing attack; and attitudes toward children grew more protective. People cared less about established political parties, and third party alternatives attracted surges of new interest.

During each of these eras, Americans felt well rooted in their personal values but newly hostile toward the corruption of civic life. Unifying institutions that had seemed secure for decades suddenly felt ephemeral. Those who once trusted the nation with their lives were now retiring or passing away. Their children, now reaching midlife, were more interested in lecturing the nation than in leading it. And to the new crop of young adults, the nation hardly mattered. The whole res publica seemed to be unraveling.

During each of these previous Third Turnings, Americans felt like they were drifting toward a waterfall.

And, as it turned out, they were.

The 1760s were followed by the American Revolution, the 1850s by the Civil War, the 1920s by the Great Depression and World War Il. All these Unraveling eras were followed by bone-jarring Crises so monumental that, by their end, American society emerged wholly transformed.

Every time, the change came with scant warning. As late as November 1773, October 1860, and October 1929, the American people had no idea how close the change was – nor, even while they were in it, how transformative it would be.

Over the next two decades or so, society convulsed. Initially, the people were dazed and demoralized. In time, they began to mobilize into partisan tribes. Ultimately, emergencies arose that required massive sacrifices from a citizenry who responded by putting community ahead of self. Leaders led, and people trusted them. As a new social contract was created, people overcame challenges once thought insurmountable and used the Crisis to elevate themselves and their nation to a higher plane of civilization. In the 1790s, they created the world’s first large democratic republic. In the late 1860s, decimated but reassembled, they forged a more unified nation that extended new guarantees of liberty and equality. In the late 1940s, they constructed the most Promethean superpower ever seen.

The Fourth Turning is history’s great discontinuity. It ends one epoch and begins another.

Yet as we reflect today on America’s entry into yet another Fourth Turning era, we must remember this: The swiftness and permanence of the mood shift is only appreciated in retrospect, never in prospect. The dramatic narrative arc that seems so unmistakable afterward in view of its consequences was not at all obvious to Americans at the time.

During the American Revolution Crisis, General George Washington early on believed his army would likely be crushed. Even as late as the mid-1780s, nearly all the founders lamented the incapacity of their feeble confederation to govern a vast, scattered, and willful citizenry.

During the Civil War Crisis, despite the rapid crescendo of deaths in major battles that each side hoped would be decisive, no clear victor emerged, Shortly before his 1864 re-election, President Abraham Lincoln (along with many of his advisors) predicted that he would likely “be beaten badly” at the polls and that his accomplishments would thereafter be dismantled by his opponents.

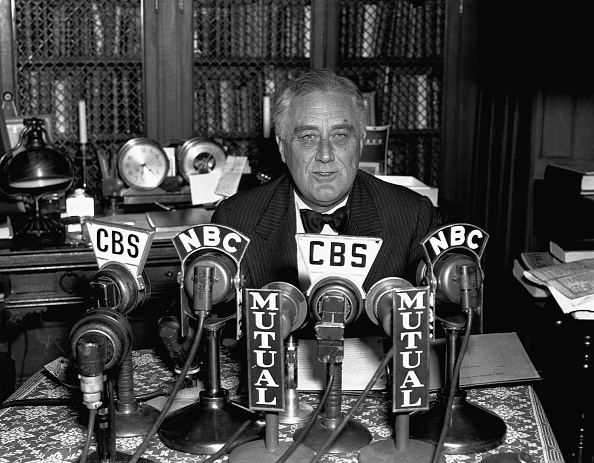

As for the Great Depression-World War II Crisis, there is a reason why this depression is called “Great”: At the end of 1940 after a decade of economic misery and New Deal activism, most Americans believed the depression had not yet ended. Unemployment was still in the double digits; deflation still loomed; and bond yields were hitting record lows. Looking back, we see President Franklin Roosevelt’s political achievements as monumental. But at the time, no one had any idea what his legacy would be until after the climax of World War II – that is, like Lincoln, not long before his death.

Similarly, as we look at our current Crisis era, we cannot yet presume to know what America will or will not accomplish by the time this era is over. Yet basic historical patterns do indeed recur.

Let’s take another look at the opening decade of our current Fourth Turning, the 2010s. And let’s compare it to the opening decade of the prior Fourth Turning, the 1930s. The parallels are striking.

Both decades played out in the shadow of a massive global financial crash, followed by the most severe economic contraction in living memory. Both were balance-sheet depressions, triggered by the bursting of a debt-financed asset bubble. Both were accompanied by deflation fears and the chronic underemployment of labor and capital. Both failed to respond to conventional fiscal and central-bank policy remedies. Terms often used to describe the 2010s economy like “secular stagnation” and “debt deflation” were in fact resurrected from celebrity economists (Alvin Hansen and Irving Fisher) who first coined them in the 1930s.

Both decades began with most measures of inequality hitting record highs, ensuring that social and economic privilege would move to the top of the political agenda. In both decades, leaders experimented with a multitude of new and untested federal policies. During the New Deal. Americans lost count of all the new alphabet-soup agencies and programs (AAA, NRA, WPA, CCC, TVA, PWA) as they did again during the Great Recession and the global COVID-19 pandemic (ARRA, TALF, TARP, QE, QT, CARES, PPP, ARP). The policy measures of the 1930s were sometimes just as head scratching as those we are subjected to today, killing pigs and plowing under cotton to save farmers (under the AAA), for example, or fixing wages to “boost” spending (under the NRA).

In both decades, populism gained new energy on both the right and the left – with charismatic outsiders gaining overnight constituencies. In both decades partisan identity strengthened, the electorate polarized, and voting rates climbed. Where a decade earlier partisans had focused on winning the “culture war,” by the mid-1930s and mid-2010s their focus had grown more existential – winning decisive political power.

In both decades, marriages were postponed, birth rates fell, and the share of unrelated adults living together rose. In both decades, families grew closer and multigenerational living (of the sort memorialized in vintage Frank Capra movies) became commonplace. In both decades, young adults drove a decline in violent crime and a blanding of popular culture – along with a growing public enthusiasm for group membership and group mobilization.

“Community” became a favorite word among the 20-somethings of the 1930s, as it became again among the 20-somethings of the 2010s. Other favorite words in both decades were “safety” and synonyms like “security” and “protection.” New Deal programs advertised all three, as have the costliest government initiatives in recent years. During the 2010s, firms began offering “feeling safe” as a benefit to their customers. “Stay safe” became a common farewell greeting. Political parties worldwide issued ever more slogans promising economic security and ever fewer promising economic growth. (Preceding the EU parliamentary elections in 2019, the universal motto of mainstream parties was “a Europe that protects.”) And in both decades, an ancient truth revealed itself: When people start taking on less risk as individuals, they start taking on more risk as groups.

Around the world, in both decades, authoritarian demagogy became a sweeping tide. The symbols and rhetoric of nationalism galvanized ever-larger crowds in real or sham support. (By 2017, governments in 30 nations were paying troll armies to sway public opinion online.) In both decades, intellectuals lent their support to grievance-based political movements based on religious, ethnic, or racial identity. Fascist language and symbols gained (or regained) popular traction in Europe – and in Russia, Joseph Stalin gained (or regained) his reputation as a national savior. In both decades, patriotism came to be equated with the settling of scores. Wolf Warrior 2, released in 2017, became the highest grossing film ever released in China largely by living up to its marketing tagline, “Anyone who offends China, wherever they are, must die.”

ln both decades, meanwhile, economic globalism was in rapid retreat. Dozens of nations began or extended border walls. The grand alliances by which large democratic powers had earlier governed global affairs were weakening. Autocrats, their political model now gaining popular appeal, had widening room to maneuver. And maneuver they did, with terrifying impunity.

Above all during these decades, social priorities in America and much of the world seemed to shift in the same direction: from the individual to the group; from private rights to public results; from discovering ideals to championing them; from attacking institutions to founding them; from customizing down to scaling up; from salvation by faith to salvation by works; from conscience-driven dissenters to shame-driven crowds.

What Lies Ahead

History is seasonal, and winter is here. A Fourth Turning can be long and arduous. It can be brief but stormy. The icy gales can be unremitting or be broken by sizable stretches of balmy weather. Like nature’s winter, the saecular winter can come a bit early or a bit late. But, also like nature’s winter, it cannot be averted. It must come, just as this winter has.

America entered its most recent Fourth Turning in 2008, placing us 15 years into the Crisis era. Each turning is a generation long (about 20 to 25 years) and it is likely that this turning will be somewhat longer than most. By our reckoning, therefore, we have about another decade to go.

What can we expect during the remainder of this era? And what will follow it?

… What typically occurs early in a Fourth Turning – the initial catalyzing event, the deepening loss of civic trust, the galvanizing of partisanship, the rise of creedal passions, and the scramble to reconstruct national policies and priorities – all this has already happened. The later and more eventful stages of a Fourth Turning still lie ahead.

Every Fourth Turning unleashes social forces that push the nation, before the era is over, into a great national challenge: a single urgent test or threat that will draw all other problems into it and require the extraordinary mobilization of most Americans. We don’t yet know what this challenge is. Historically, it has nearly always been connected to the outcome of a major war – either between America and foreign powers, or between different groups within America, or both.

War may not be inevitable. Yet even if it is not, the very survival of the nation will feel at stake. The challenge will require a degree of public engagement and sacrifice that few Americans today have experienced earlier in their lives. Remnants of the old social and policy order will disintegrate. And by the time the challenge is resolved, America will acquire a new collective identity with a new understanding of income, class, race, nation, and empire. For the rising generation of Millennials, the bonds of civic membership will strengthen, offering more to each citizen yet also requiring more from each citizen.

In any case, sometime before the mid-2030s, America will pass through a great gate in history, commensurate with the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the twin emergencies of the Great Depression and World War lI. The risk of catastrophe will be high. The nation could erupt into insurrection or civil conflict, crack up geographically, or succumb to authoritarian rule. If there is a war it is likely to be one of maximum risk and effort – in other words, a total war – precisely because so much will seem to rest on the outcome.

Every Fourth Turning has registered an upward ratchet in the technology of destruction and in humanity’s willingness to use it. During the Civil War, the two capital cities would surely have incinerated each other had the two sides possessed the means to do so. During World War lI, America enlisted its best and brightest young minds to invent such a technology – which the nation swiftly put to use. During the Millennial Crisis. America will possess the ability to inflict unimaginable horrors and confront adversaries who possess the same.

Yet Americans will also gain, by the end of the Fourth Turning, a unique opportunity to achieve a new greatness as a people. They will be able to solve long-term national problems and perhaps lead the way in solving global problems as well. This too is part of the Fourth Turning historical track record.

The U.S. Civil War, for example, reunited the states, abolished slavery, and accelerated the global spread of democratic nationalism. The New Deal and World War II transformed America into a vastly more affluent and equitable society than it had been before – and into a nation powerful enough to help many other countries grow more prosperous and democratic themselves throughout the rest of the 20th century.

In about a decade, perhaps in the early or mid-2030s, America will exit winter and enter spring. The First Turning will begin. The mood of America during this spring season will please some and displease others. Individualism will be weaker and community will be stronger than most of us recall from circa-2000. Public trust will be stronger, institutions more effective, and national optimism higher. Yet the culture will be tamer, social conscience weaker, and pressure to conform heavier.

If the current Fourth Turning ends well, America will be able enjoy its next golden age, or at least an era that will feel like a golden age to those who build it. Come this spring, America’s chief preoccupation will be filling out and completing the new order whose rough framework was only hastily hoisted into place at the end of the winter.

Inevitably, that completion will in time generate new tensions and move America into yet another (summer) season by the 2050s. But all this takes us far ahead of the central focus of our story, which remains the outcome of winter.

“There is a mysterious cycle in human events,” President Franklin Roosevelt observed in the depths of the Great Depression. “To some generations much is given. Of other generations much is expected. This generation has a rendezvous with destiny.”

This cycle of human events remains mysterious. But we need not stumble across it in total surprise or remain ignorant of why it arose, what drives it, how it behaves, or where it’s going. Indeed, we must not. For today’s generations have their own rendezvous with destiny.

Excerpted from The Fourth Turning Is Here: What the Seasons of History Tell Us About How and When This Crisis Will End, by Neil Howe (Simon & Schuster).

Tell us if you are enjoying the “What We’re Reading” series and let us know what you are reading this summer at [email protected].

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD