The Hidden Power Of Legal Monopolies…

How To Spot Them… And The Best One To Buy Now

| This is Porter & Co.’s The Big Secret On Wall Street, our flagship publication that we publish every Thursday at 4 pm ET. Once a month, we provide to our paid-up subscribers a full report on a stock recommendation, and also a monthly extensive review of the current portfolio… At the end of this week’s issue, paid-up subscribers can find our Top 3 “Best Buys,” three current portfolio picks that are at an attractive buy price. You can go here to see the full portfolio of The Big Secret.

Every week in The Big Secret, we provide analysis for non-paid subscribers. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, to access the full paid issue, the portfolio, and all of our Big Secret insights and recommendations, please click here. |

Behind a forbidding eight-foot-tall fence in Worthington, Ohio, a mysterious 5,000-ton machine whined and grumbled.

The first mistake Chien-Min Sung made was talking about it.

The former General Electric employee had signed an ironclad confidentiality agreement when he first stepped behind the fence in 1977. But, 12 years later, Mr. Sung’s greed got the better of him.

Enticed by a million-dollar offer from Korean manufacturer ILJIN Corporation, Sung boxed up 487 pages of trade secrets and shipped them overseas – allowing ILJIN to build its very own version of GE’s fabled, jealously-guarded diamond-making machine.

GE was serious about protecting its treasure trove, the then-$1 billion industrial diamonds business. Not nearly as flashy as jewelry-quality gems, but much more useful, GE’s proprietary lab-grown diamonds cut glass, polished blades, and powered precision machinery all over the globe.

Back in the 1980s, almost no one else had figured out how to make artificial diamonds – an alchemist-like feat reminiscent of man’s long quest to turn everyday objects into gold.

GE’s main competitor was the lab diamonds division at De Beers – the almost cartoonishly-evil South African diamond cartel famous for its cutthroat “blood diamond” mining practices (and for the iconic “Diamonds are forever” marketing campaign). Between the two of them, GE and De Beers cornered 90% of the industrial diamonds market, with no room for anyone else.

Until ILJIN jumped into the (diamond) ring, that is…

By the end of the summer of 1989, the Korean firm had built its own magical diamond machine and siphoned away three of GE’s prime clients, along with $100,000 a month (in 1980s dollars) in sales.

GE had eyes everywhere, and retribution was swift and severe. Lawyers and detectives swarmed Sung’s house, carting off every relevant sheet of paper they could find. GE sued Sung and ILJIN, with the stated goal to drive ILJIN out of business. Sung pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months of house arrest. ILJIN was forced to destroy its diamond machine and back out of the gem business for the next seven years.

It was back to De Beers and GE, sitting in a tree, k-i-s-s-i-n-g.By then, U.S. antitrust watchdogs thought the two rivals were a little too close to each other…

Who You Gonna Call? Trustbusters

Monopolies, of course, are illegal – except in certain government-sanctioned cases like the U.S. Postal Service and national sports leagues. A monopoly is when one business is the only – or main – supplier of a good or service in a market. When one or two companies dominate the industry, they can essentially set the price of the product however they like. That’s horrible for consumers, but great for the businesses.

The U.S. government has been cracking down on monopolies since 1890, when Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to prohibit this kind of anti-competitive practice. The Sherman Act and several other pieces of supporting legislation forced the breakup of the U.S.’s first monopolies, like John D. Rockefeller’s huge and predatory Standard Oil.

But lots of big businesses still want to pass Go and collect $200. The trick is to do it without landing in jail.

U.S. Assistant Attorney General Anne K. Bingaman, a notorious trust-buster, had been watching the GE-De Beers duopoly with a suspicious eye for quite some time in the late 1980s. She just needed an excuse to prosecute – and Ed Russell, a disgruntled former GE vice president, handed it to her one afternoon in 1991…

Russell had tanked his own career by having an inter-office affair with a girl from Marketing. He married his new squeeze and let her run his division. After companywide complaints, he was sacked – and was now seething at losing his $205,000-a-year salary and pension plan.

He claimed he’d overheard a private meeting at a London hotel where GE and De Beers officials conspired to raise diamond prices – effectively melding the two “rivals” into one big, illicit cartel. The assistant attorney general was all ears. In February 1994, GE and De Beers were indicted by a federal grand jury in Columbus, Ohio, under charges of unlawfully fixing international diamond prices.

De Beers – already in hot water for human-rights violations in multiple countries, and beginning to lose ground, literally, to Russian and Canadian diamond mines – backed hastily out of the U.S. to avoid prosecution and didn’t return to do business in America for another decade.

GE, whether from bravado or from a clear conscience, stood its ground and attended the court proceedings. “We want to go all the way with this one,” said CEO Jack Welch.

His confidence, it turned out, paid off. After a five-week trial, the judge dismissed all charges and GE was allowed to resume its industrial diamond duopoly unmolested. Ed Russell, the wanna-be whistleblower, recanted his testimony via sworn affidavit and slunk off to the unemployment office. And thwarted trustbuster Anne K. Bingaman set her sights on her next target: Microsoft.

What’s interesting is what happened to GE stock over the next six years or so: an almost instantaneous 1,200% rise.

The eventual downfall of the GE conglomerate, which Porter predicted, came a decade later, in 2011. But that six-year-long bull run should tell you that, in 1994, the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) was on to something…Antitrust lobbyists lurk on the edges of industry, looking for especially fat and juicy companies to drag away. That’s why you should watch the trustbusters. Look where they’re looking. When they try to bust a monopoly, and fail, that’s a signal that the company is doing a little too well.

Barely Legal

Firms like ‘90s GE… the ones that are successful enough to attract the ire, and the litigation, of major regulatory bodies… often dodge antitrust law and come out unscathed in a ballsy Indiana Jones-grabbing-the-hat move. Then they keep on mopping up market share and paying dividends (for a few years, at least).

We like to call these companies legal monopolies. And we like to invest in them, too.

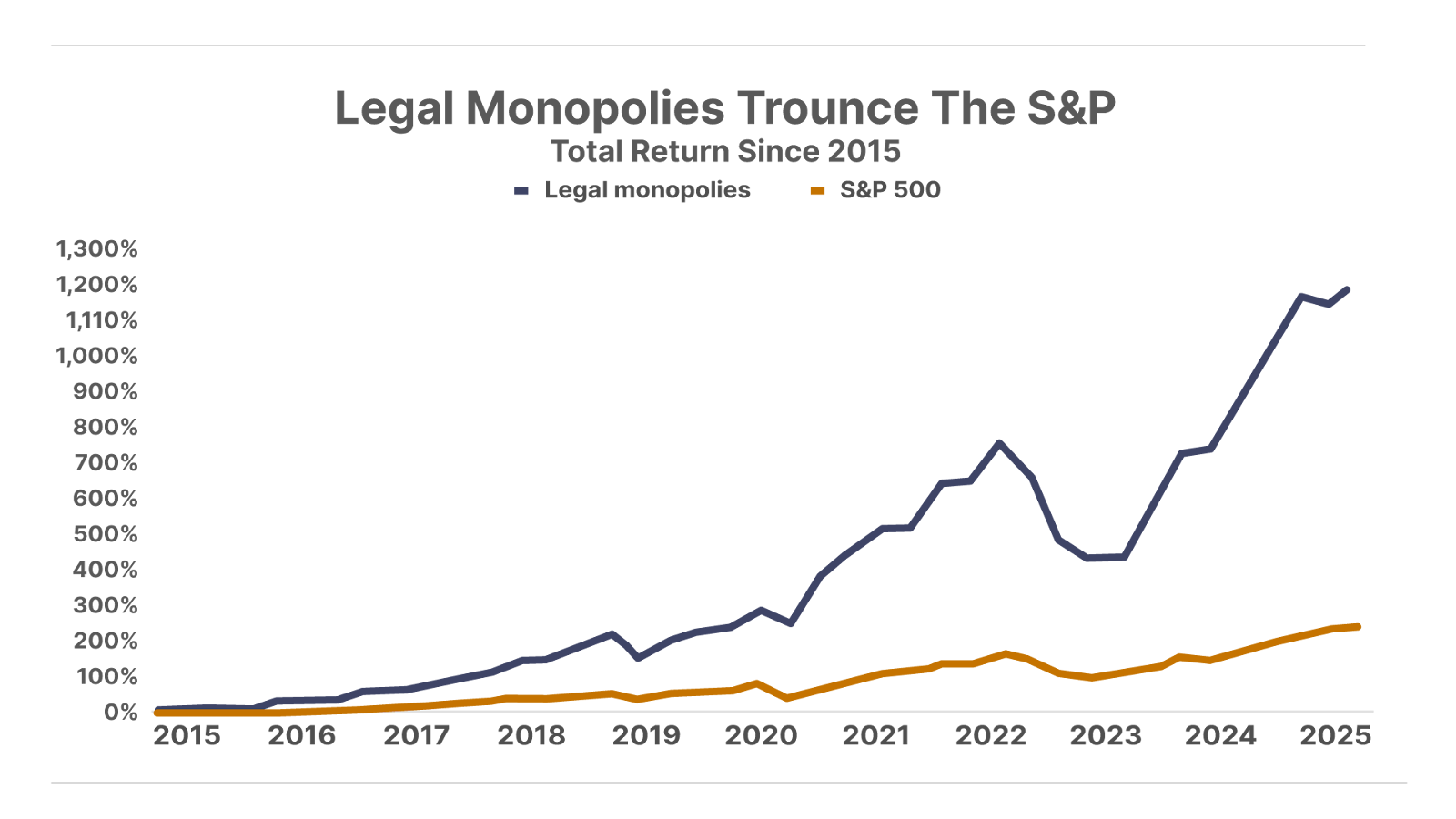

Failed antitrust litigation – like the DOJ’s dropped suit against GE – is actually a remarkable predictor for a stock’s success. A basket of the 10 largest tech companies that have beaten major antitrust suits over the past decade trounces the performance of the S&P 500 during that period by some 976 points:

These are all companies that have captured the lion’s share of their market: Microsoft (MSFT) has a 70% share of computer operating systems. (No wonder Anne Bingaman went after it.) Nvidia (NVDA) has almost 85% share of the data-center artificial-intelligence GPU chip market. And ASML (ASML) produces essentially 100% of high-end EUV lithography equipment.

Somehow, they’ve managed to beat the hungry trust-busters… so far, anyway.

Not surprisingly, the 10 names on this list – Alphabet (GOOG), Meta Platforms (META), Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (APPL), Adobe (ADBE), Intuit (INTU), Amazon (AMZN), VISA (V), Qualcomm (QCOM), and Nvidia (NVDA) – include several of Porter’s biggest winners over the years.

Legal monopolies all bear a family resemblance to each other. They have dominant market share. They have enviable pricing power. Given a lack of alternatives for customers, these companies likely have highly predictable and mostly recurring revenue streams. All of that means big profit margins that flow to the bottom line.

If you want a quick, shorthand way to screen for superior companies, try the keywords “failed antitrust suits” and see where it gets you.The business we recommend in this issue of The Big Secret passes this test. It’s a textbook legal monopoly that dodged a hefty antitrust lawsuit in April 2025, and then continued on its merry way as a $35 billion company that manufactures nearly one-fifth of the global supply of… well, read on.

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.