Better Than Buybacks, Dividends, or Acquisitions: A Radical New Use of Corporate Cash

In the early 1990s, executives at The Quaker Oats Company – the maker of oatmeal, Life cereal, and grits – were on top of the financial world.

Over the previous decade, they had grown the once-sleepy breakfast-food leader into a diversified food-and-beverage business. At the heart of this transition was the company’s 1983 purchase of Gatorade.

Quaker had used the same wholesome TV-advertising strategy (replacing oatmeal warming up your ribs for Gatorade quenching that “deep-down body thirst”) and extensive relationships with the nation’s large retail chains to grow Gatorade from a niche sports energy drink, to a billion-dollar global brand.

This was an impressive feat. When companies acquire brands operating outside of their core businesses, the deals are usually less successful. At the time, edgy Gatorade, with its fluorescent rainbow of flavored beverages that appealed to younger, active consumers, was not something that the frumpy oatmeal crowd was drawn to.

But Quaker management – using breakout ad campaigns (“Be like Mike”) and aggressive distribution efforts to what it called “points of sweat” – made it work. Tasting success, they wanted to expand their offerings even more, by moving further from its breakfast-cereal roots to become a food-and-beverage empire.

The company set its sights on replicating Gatorade’s success with another promising beverage brand. It believed Snapple, at the time a quirky iced-tea upstart, was the perfect candidate. So, in 1993 – a little over 10 years after it acquired Gatorade for around $200 million – Quaker Oats bought Snapple for a whopping $1.7 billion… a price that many on Wall Street said was $1 billion too high (and even pushed Coca-Cola out of the bidding battle).

The deal was a disaster from the beginning.

Quaker’s corporate structure and traditional marketing tactics clashed with Snapple’s startup culture and offbeat advertising. Quaker’s retail network centered on supermarkets and large chains, while Snapple had thrived by relying on small retailers. Snapple was beloved as a grassroots, alternative brand, while Quaker was as buttoned-up as they come.

Snapple quickly devolved from an exciting premium beverage into a dull, mainstream brand. It pumped millions into ad campaigns and product giveaways, but sales plummeted nonetheless – dropping every year from the $700 million before the sale to around $440 million in 1997.

Out of options, a frustrated Quaker team sold Snapple to privately held Triarc Beverages for just $300 million. The failed acquisition cost Quaker $1.4 billion in less than four years… the equivalent of losing $1.6 million every day.

The disaster led to both the president and chairman of Quaker Oats losing their jobs… and to the company’s eventual takeover by snack-and-beverage giant PepsiCo in 2001.

Good and Bad Uses of Corporate Cash

Quaker’s story isn’t anything unusual, unfortunately. Financial history is littered with similar tales of foolish deals that have destroyed trillions in shareholder value.

In hindsight, the purchase of Snapple seems like an obviously bad idea – the price was too high, the brand personality was not a fit, and growth synergies with Gatorade were not apparent. So why did Quaker pour $1.7 billion into such a risky proposition?

Like many problems in modern finance, the answer traces back to today’s monetary system itself.

Most mid- to large-size companies generally have limited options for using excess cash. They can reinvest that cash back into their business in a few ways… hold that cash on their balance sheet (in bank deposits or cash equivalents like U.S. Treasury bills and short-term commercial debt)… invest in assets (like longer-term sovereign debt, equities, or property)… attempt to “buy growth” via acquisitions… or return it to shareholders in the form of dividends or share buybacks.

Reinvesting in their business is generally the lowest-risk option. A company should be adept at running its own business, as opposed to investing elsewhere. However, there are often limits to how much cash can be deployed this way, particularly for mature or highly capital efficient companies.

Holding cash directly should be the next lowest-risk option. A healthy cash reserve ensures a company has the means to weather difficult economic environments. However, in an economy anchored with a fiat monetary system, cash is guaranteed to lose value over time. As a result, short-sighted investors tend to punish companies for holding significant quantities of cash.

Outside investments also come with significant limitations. Real estate is too illiquid to be a primary reserve asset. The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) restricts operating (non-investment) companies from owning more than 40% of their assets in securities like stocks. And though bonds can offer a higher yield than cash, they can also carry credit and interest-rate risk – and still often produce a negative real return after inflation.

Acquisitions are typically high risk. When successful, they can generate more revenue and increased profits – for example, Quaker Oats buying Gatorade – and boost a company’s earnings per share (“EPS”), the most coveted metric on Wall Street. However, when they don’t work out, as with Quaker Oats’ purchase of Snapple, they’re among the surest ways to destroy shareholder value.

Finally, a company can return excess cash to shareholders, either via dividends or share buybacks. Investors have long preferred dividends – because it is a guaranteed cash payment. But share buybacks have become much more popular recently, with total repurchases by public companies globally nearly tripling over the last 10 years.

Unlike dividends, share buybacks don’t produce taxable gains for investors. And, more important, like acquisitions, they can boost a company’s EPS – and the value of an investor’s shares – by reducing the total number of shares outstanding… something Wall Street increasingly rewards corporate executives for.

However, as Warren Buffett has noted, buybacks are a double-edged sword. They can also destroy shareholder value if used indiscriminately. Buffett explains…

“The math isn’t complicated: When the share count goes down, your interest in our many businesses goes up. Every small bit helps if repurchases are made at value-accretive prices.

“Just as surely, when a company overpays for repurchases, the continuing shareholders lose. At such times, gains flow only to the selling shareholders and to the friendly, but expensive, investment banker who recommended the foolish purchases.”

In other words, buybacks are only beneficial if a company’s stock is trading for less than it’s actually worth.

Unfortunately, in recent years, an increasing number of companies have issued large, price-agnostic buyback plans that purchase shares regardless of valuation.

Some companies have taken this logic to the extreme – taking on large amounts of debt (essentially creating a negative cash position) to fund acquisitions or buy back shares.

Given the obvious downside and relatively limited upside of the other options mentioned above, it shouldn’t be surprising that corporate executives often turn to these higher-risk strategies with potentially higher rewards.

After all, they see it this way: an acquisition or buyback plan could dramatically boost the stock price (and management compensation) – while playing it safe yields few rewards.

However, this could soon begin to change. Companies now have another option for managing cash, due in large part to one man’s pioneering efforts.

A Maverick Makes Millions Managing Data

Paid-up Big Secret readers may recall the story of Michael Saylor – the maverick founder and CEO of business-intelligence and analytics firm MicroStrategy (Nasdaq: MSTR) – who we reported on in October 2022.

Saylor – who graduated from MIT with majors in aeronautics and astronautics – launched MicroStrategy in 1989 when he was 24 years old. His aim was to become a leader in data-mining solutions, monetizing the growing but often disorganized streams of data many companies were beginning to generate. And he found success relatively quickly…

MicroStrategy developed software for forecasting business trends, such as which of a company’s franchise locations would generate the most revenue or which products were likely to sell best at a particular store. This information could help a large company save tens of millions of dollars.

Saylor was able to sell McDonald’s on the idea, and in 1992, the fast-food giant signed MicroStrategy’s first major deal, a $10 million contract.

Saylor doubled MicroStrategy’s revenue in each of the next four years. The stock price soared more than 2,000% – no doubt boosted by the burgeoning dot-com bubble – making Saylor a billionaire by 1999.

Unfortunately, the boom times didn’t last. MSTR shares plunged in March 2000 when the company announced it would restate its financials for the previous two years to comply with new federal accounting guidelines on revenue reporting. The stock finally bottomed – down more than 99% from its $3,000-per-share peak – when the company settled with the SEC in December 2002, with Saylor and other executives avoiding any admission of wrongdoing.

As recently as four years ago, MicroStrategy was a mature, slow-growing company generating roughly $500 million in revenue and $100 million in operating cash flows per year. And this was reflected in the price of its shares, which remained more than 95% below their prior peak.

But everything changed following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Michael Saylor’s Revolutionary Bitcoin Strategy

As governments around the world unleashed the most aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus in history, Saylor believed massive inflation would follow and wipe out the value of the company’s $500 million cash reserves.

After extensive research into hard assets, Saylor became convinced that Bitcoin (BTC) was the ultimate hedge against fiat-currency debasement. And he immediately made accumulating and holding Bitcoin a major strategic priority for MicroStrategy.

He started by converting half of MicroStrategy’s cash reserves into Bitcoin in late summer 2020, following a Dutch auction, which allowed existing shareholders of MicroStrategy to sell if they weren’t fully on board with this new, untested strategy.

After a favorable reaction from shareholders, and the company’s share price (which quickly rose to its highest level in decades), Saylor went “all in” on Bitcoin. He converted the remainder of the company’s cash into “digital gold” – and even took on more than $2 billion in debt (via both traditional and convertible-bond issues) to buy more. (Porter & Co recommended one of these convertible bonds in the October 14, 2022, Big Secret. Subscribers who invested then, and sold the bonds in November 2023 as we recommended, reinvesting 50% of the proceeds into Bitcoin, would have earned 117% to date.)

In the years since, Saylor has continued to aggressively accumulate huge amounts of Bitcoin, using excess cash flows, additional convertible debt offerings (including a $500 million convertible offering proposed just this week), and by issuing nearly $3 billion in new shares.

Today, MicroStrategy is arguably two businesses… the first is the stable but slow-growing legacy analytics business, and what Saylor calls the world’s first “Bitcoin development company” is the other. As of this week, the company holds 205,000 Bitcoins (acquired at an average price of $33,706 versus BTC’s current price of $70,000), just shy of 1% of all the Bitcoins that will ever be created – making it the largest corporate holder of the cryptocurrency by far.

MicroStrategy’s equity issuance is particularly noteworthy. As the value of the Bitcoin on MSTR’s balance sheet has risen over the past several months, the total market value of its shares has risen even faster. Saylor has been taking advantage of this mispricing by issuing additional shares at these lofty valuations and then redeploying that capital into more Bitcoin.

Issuing this new stock has technically diluted MicroStrategy investors’ ownership of the legacy business over time. However, this strategy has allowed the company to grow its “Bitcoin per share” (“BPS”) significantly. This metric – arguably a more important driver of MicroStrategy’s current valuation than EPS and other traditional measures – has grown consistently since 2020 to nearly 0.01 BPS today. This has effectively created a virtuous cycle that has continued to push shares higher as Bitcoin has risen to new highs.

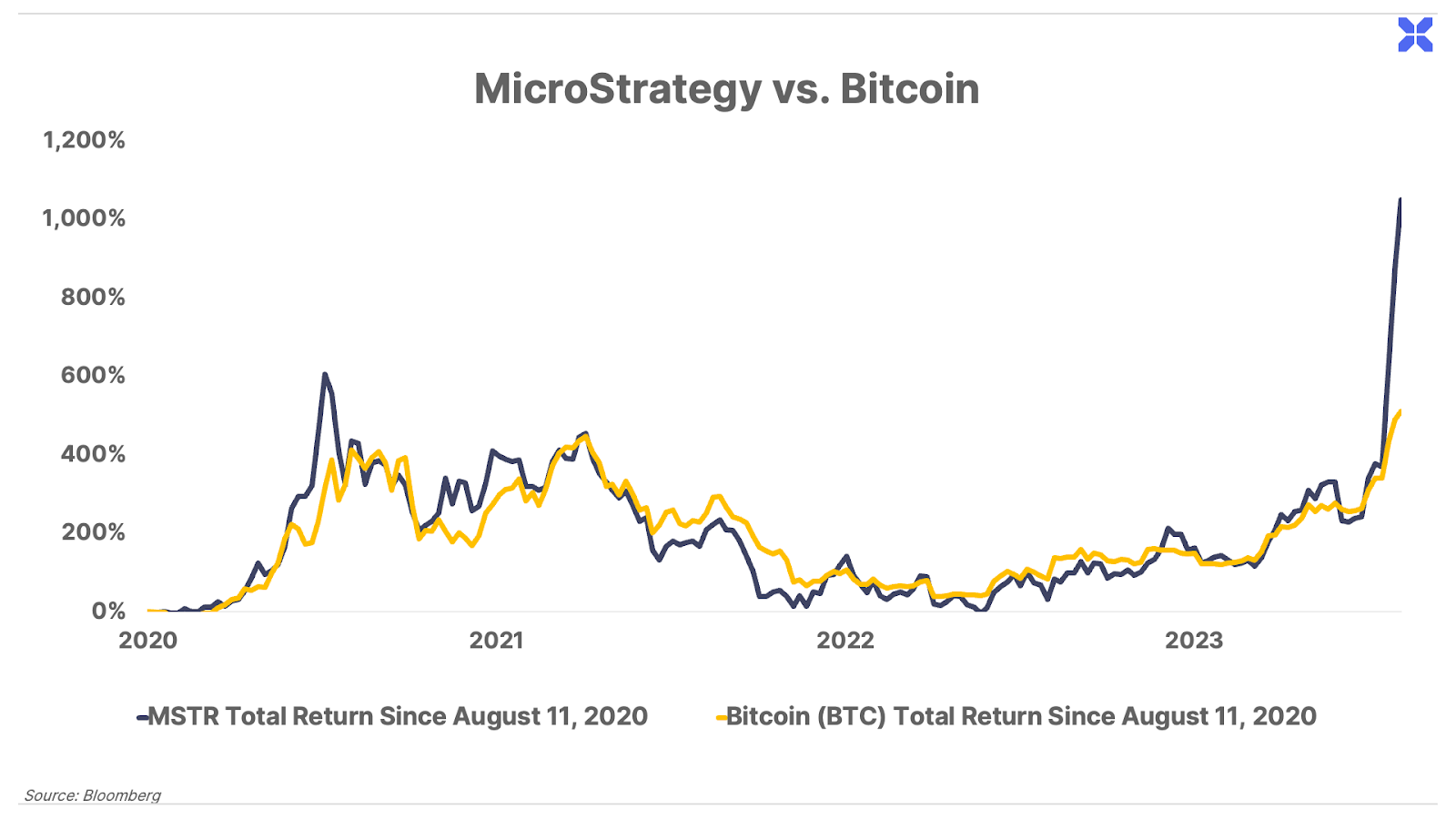

In essence, Saylor has made MicroStrategy an increasingly leveraged bet on the price of Bitcoin, and its recent price performance reflects that. As you can see, MSTR has recently begun to dramatically outperform Bitcoin after initially only keeping pace with the crypto since Saylor adopted the strategy…

Saylor’s all-in Bitcoin strategy has garnered plenty of criticism from Bitcoin skeptics. While it has allowed MicroStrategy to benefit tremendously from Bitcoin’s recent rally, this leverage applies both ways.

If the price of Bitcoin were to fall dramatically, MicroStrategy’s more than $2 billion in outstanding debt could become a problem – particularly if the company’s legacy business also slowed for any significant period, as would likely happen in a recession. In a worst-case scenario, equity investors could be wiped out.

However, critics focused solely on Saylor’s aggressiveness are missing a more important story.

Saylor has pioneered a strategy that – if used appropriately – could revolutionize corporate financial management.

How Bitcoin Could Change Corporate Finance for the Better

By simply allocating a reasonable portion of their cash reserves to Bitcoin – a scarce, liquid asset that is likely to appreciate against all other assets over the long run – companies can escape the traditional dichotomy of pursuing safety or growth.

This measured (as opposed to all-in) strategy can provide companies with the security of a substantial cash position without the fear of currency debasement or being punished for owning a depreciating asset. And it offers the opportunity to boost long-term shareholder value when riskier options – such as questionable acquisitions or overpriced share buybacks – don’t make great sense. And this conservative strategy also avoids the potential risks and volatility that comes with Saylor’s more aggressive approach.

Data show at least 38 publicly traded companies have adopted this kind of Bitcoin reserve strategy. However, there has been one significant hurdle to increased adoption. That is the way Bitcoin had been treated under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”), until recently.

GAAP defined Bitcoin and other crypto assets as “indefinite-lived intangible assets.” This is the same classification given to intangible assets like copyrights and other intellectual property.

In practice, this meant that a company would have to write down the value of any Bitcoin it held when its price moved lower. However, it could only record a gain on that Bitcoin when it sold the position.

This rule has almost certainly acted as an impediment to wider adoption, as the GAAP value of Bitcoin held for any meaningful time would likely be far below its actual market value – leading to financial frustration for management and confusion for shareholders.

However, that is no longer the case. Thanks mainly to Saylor’s advocacy, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”) voted unanimously in September 2023 to reclassify Bitcoin and some other crypto assets. Beginning in 2025, companies will be required to use fair-value accounting for Bitcoin, but companies can adopt the change early if desired.

This change provides a viable new option for managing company cash – it allows management to treat Bitcoin like traditional financial assets immediately. They can begin to recognize (and benefit from) its long-term price appreciation – opening the door to its increased adoption as a reserve asset.

Broad adoption of a Bitcoin reserve strategy could ultimately encourage companies to take a longer-term strategic outlook, rather than the myopic, quarter-to-quarter perspective that is so common and unproductive today – which would be a big positive for the economy as a whole and a significant advantage for long-term investors.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD