A Company That’s In A Category All Its Own

When The Army Needs Advice, It Turns To These Guys

| This is Porter & Co.’s The Big Secret On Wall Street, our flagship publication that we publish every Thursday at 4 pm ET. Once a month, we provide to our paid-up subscribers a full report on a stock recommendation, and also a monthly extensive review of the current portfolio… At the end of this week’s issue, paid-up subscribers can find our Top 3 Best Buys, three current portfolio picks that are at an attractive buy price. You can go here to see the full portfolio of The Big Secret. Every week in The Big Secret, we provide analysis for non-paid subscribers. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, to access the full paid issue, the portfolio, and all of our Big Secret insights and recommendations, please click here. |

Three olive-drab Army trucks. A full 44-man unit of helmeted soldiers.

And one stubborn guy who wouldn’t get out of a green leather armchair.

It was 1944, and the U.S. Army had just forcibly taken over the Chicago Montgomery Ward plant “for the successful prosecution of the war.” Montgomery Ward’s CEO, Sewell Avery – the man in the armchair – was having absolutely none of it.

The brick-and-mortar headquarters of America’s top mail-order catalog retailer wasn’t the first civilian establishment that Uncle Sam commandeered for wartime purposes. Ford Motor, General Motors, and Alcoa Aluminum had all dutifully handed over their production lines to help President Franklin Roosevelt’s big, booming World War II effort.

But Montgomery Ward was the only seized company whose products had zero to do with World War II: it didn’t stock munitions, metal for planes, or rubber for gas masks. Just manure-proof shoes, overalls, and luxury goods like fur coats for folks who lived far from big-city department stores.

What Montgomery Ward did have was Sewell Avery… a battle-axe, right-leaning CEO who hated everything about FDR’s spendy New Deal.

Avery had built a retail empire on the principles of hard work, bootstraps, and what Time magazine called “tight-fisted, cash-hoarding, non-expansionist policies.” When he wasn’t slashing pension plans and axing employees who disagreed with him (in his words, “If anybody ventures to differ with me…I throw them out of the window”) he was campaigning vociferously against the welfare state.

Like many people with bad attitudes, Avery was a phenomenally successful CEO – having pivoted Montgomery Ward from a $5.7 million loss (in 1930s dollars) in 1932 to a $20.4 million profit in 1943.

Of course, he did have a secret weapon in his back pocket – more on that later…

With his cash hoard from Montgomery Ward, Avery bankrolled prominent anti-New-Deal activists like the American Liberty League and the Church League of America. Plus, he publicly opposed FDR’s pro-labor stance and refused to allow Montgomery Ward employees to unionize… all of which meant President Roosevelt hated Sewell Avery just as much as Avery hated him.

And that early evening in December 1944, FDR decided it was time to teach Mr. Avery a personal lesson on sharing his toys with others.

First, Roosevelt ordered in the 44-man unit – and then issued an announcement that Montgomery Ward was now a “ward” of the state. When Mr. Avery didn’t respond, a squadron stormed the stairs and breached his office – a tasteful affair decorated with green leather accents.

The commanding officer announced, “Under authority vested in me by the President of the United States, I am taking over this plant.”

“No,” Avery replied succinctly. He refused to budge.

And that’s how the Associated Press came to capture an image of the CEO of the nation’s largest mail-order concern being lugged out of his own office in a cross between a frog march and a fireman’s carry.

On his way out of the office, Avery turned to U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle, who’d flown in to supervise the proceedings, and hit him with the worst curse words he knew:

“To hell with the government… you New Dealer!”

Liberal U.S. District Judge William H. Holly issued a temporary injunction barring Avery from his own workplace, but his plight didn’t last long. After a four-day military occupation of the Montgomery Ward plant – covered in detail by the national press – Americans were in an uproar over FDR’s “Gestapo methods.” Mississippi Senator James Eastland warned, “If the President has power to take over Montgomery Ward, he has the power to take over a grocery store or butcher shop in any hamlet in the U.S.”

It was pretty clear to politicians on both sides of the aisle that Roosevelt’s Montgomery Ward coup was a politically-motivated hit job – and, after a pointed investigation by Democratic conservative firebrand Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada, who actually did cause a guy to fall out of a window once, the Army withdrew.

Sewell Avery was allowed to resume business as usual… without pension plans or employee insurance, just the way he wanted.

He retired in 1955 with a $327 million (in 1950s dollars) fortune, remaining a notorious tightwad until the end. However, he did gift one surprising bit of goodwill to the world: a little ditty called “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” which swept the nation after Mr. Avery graciously agreed to publish lyrics written by a low-level Montgomery Ward employee one Christmas.

He left his secret wealth-building weapon behind, too.

And he’d likely rise up from his resting place in Rosehill Cemetery, in Chicago, and yell “To hell with the government, you New Dealer!” if he ever found out who wields that secret weapon now…

To Hell With The… Oh Well

Montgomery Ward wasn’t Sewell Avery’s first successful turnaround. In 1905, many years before he revitalized the world of mail order, he’d also taken over a tiny company called U.S. Gypsum, led it to profitability during every year of the Great Depression, and helped it get its new product – an invention called Sheetrock – into construction builds all over the United States.

And he’d used the exact same secret weapon back then.

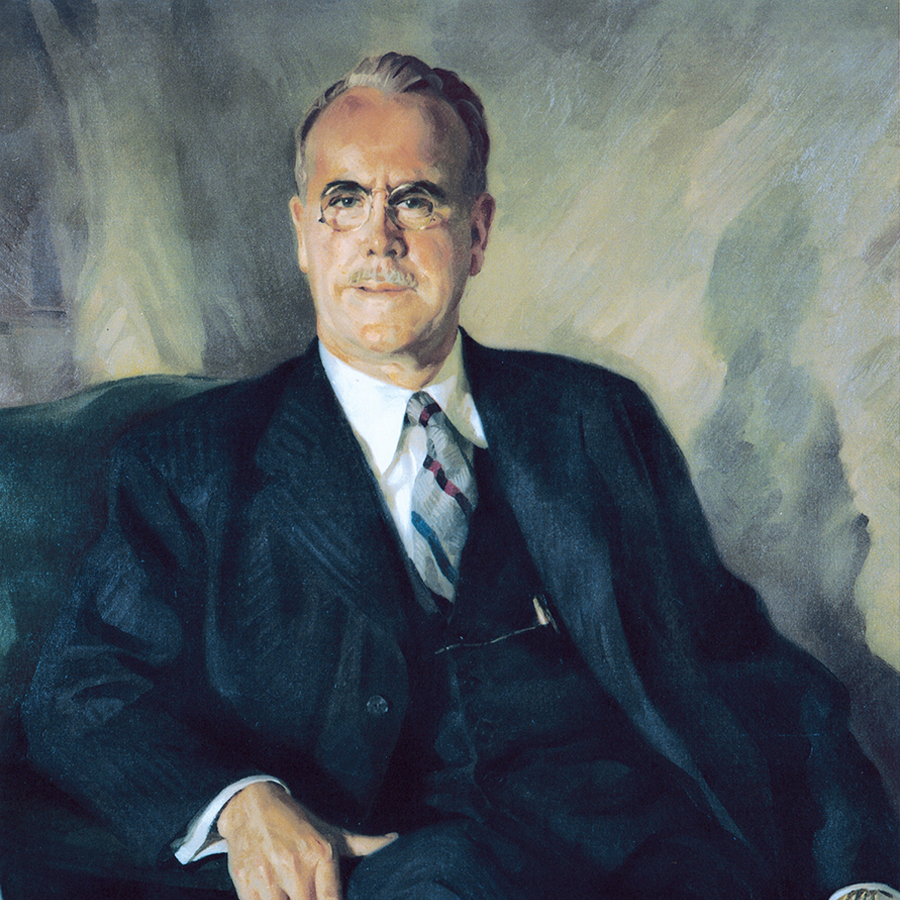

Avery’s secret was an unassuming little man named Edwin, who wore round Teddy Roosevelt-esque spectacles and had a passion for efficiency. He specialized in cutting costs and boosting performance, and he’d created a little mini-corporation devoted solely to making bigger companies run better.

Edwin was very, very good at his job. He had a gift for instantly diagnosing problems and offering vivid solutions: “Too many motors and too few dynamos” was his assessment of the manager-heavy culture he found at U.S. Gypsum. Plus, he was brilliant with people: as one of his partners explained, he had “a certain spiritual quality and sense for human relationships” that seldom steered him wrong.

Over the years, Edwin’s successful turnaround clients included Sewell Avery (first at U.S. Gypsum and then at Montgomery Ward), the Illinois State Railroad, General Mills, and Goodyear Tire. He had a little black book of frequent fliers who he referred to, for some unknown reason, as his “Marines.”

And, starting in the fall of 1940, he scored his biggest client of all… not the Marines, but the U.S. Navy.

At the cusp of World War II, Europe was engulfed in flames, Asia wasn’t far behind, and America’s military machine wasn’t ready. The U.S. Navy, bloated with bureaucracy and paper trails, was in desperate need of something it didn’t yet understand: modern management.

That’s when the newly-appointed Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, made a decision that would ripple through time and transform both the Department of Defense (“DOD”) and the American business landscape.

He decided to deploy Sewell Avery’s secret weapon.

What began as a short-term wartime engagement for Edwin’s firm turned into an enduring relationship that redefined the role of consulting in the public sector. Today, generating around $11 billion in annual revenue and with a market cap of $13 billion, it is the largest government-focused management consulting firm in the U.S., with tens of thousands of employees.

It’s that company (with apologies to those among us who hate the government) that we are recommending in this issue.

A High Voltage Play In Government IT Services

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.