Using Cash Positions As A Contrarian Indicator

Extreme Valuations Point To Sky-High Risk

| This is Porter & Co.’s The Big Secret on Wall Street, which we publish every Thursday at 4 pm ET. Once a month, we provide our paid-up subscribers with a full report on a stock recommendation, and also a monthly extensive review of the current portfolio… At the end of this week’s issue, paid-up subscribers can find our Top 3 “Best Buys,” three newly added portfolio picks that are at an attractive buy price. You can go here to see the full portfolio of The Big Secret. Every week in The Big Secret, we provide analysis for non-paid subscribers. If you’re not yet a subscriber, to access the full paid issue, the portfolio, and all of our Big Secret insights and recommendations, please click here. |

Henry Neuwirth’s final helicopter flight lasted just two minutes.

Amateur pilot Neuwirth had barely taken off from his helipad in Middletown, New Jersey, and headed on a joy ride over the East River when he – and his machine – exploded into a ball of flame.

It was July 28, 1973, and Neuwirth was just 40 years old.

Nine years later, in nearby Manhattan, death came knocking for Frederic Mates.

Perhaps inspired by his own last name, Mates had moved to New York City during his midlife crisis and opened a singles bar. After eight years of shimmying through the disco scene, he dropped dead of a heart attack at age 50.

The Grim Reaper took a few more decades to reach David Ehlers, who’d spent the late 1980s managing a Blockbuster Video franchise in the U.S. island territory of Guam. Afterward, he settled in Las Vegas as a “gambling investment advisor,” which meant he sent spies to casinos to see which gaming machines got the most use, and then recommended those stocks to his subscribers.

In 2021, at age 89, Ehlers finally cashed out for good after breaking his hip.

On the surface, these three men don’t seem to have much in common — just slightly offbeat lives that took an unusual trajectory.

But they were all bound together by a single mistake they made in the early 1970s… one bad decision that, in hindsight, almost seems like a curse…

Before Neuwirth, Mates, and Ehlers met their strange ends, they each managed one of the top-performing mutual funds of the late 1960s, fueled by “unstoppable” growth stocks like Polaroid, Xerox, and IBM. The Mates Investment Fund was the top performer of 1968, turning in a net asset value gain of 153%. Helicopter pilot Henry Neuwirth’s Neuwirth Fund was the second-highest flier at a 91% gain, and Ehlers’ Gibraltar Growth Fund came in third at 73%.

No one talks about these old funds today. You have to dig through deeply buried newspaper archives to find any mention of their names. It takes even more research to uncover the odd fates that befell their managers after the “go-go” market cratered in January 1973 and wiped out nearly all the gains these funds had notched for their trusting investors.

Unfortunately for these hot-shot managers, they (and many others, including more well-known names like Fred Carr and Gerry Tsai) all made the same error. They were overinvested, with very little spare cash on hand.

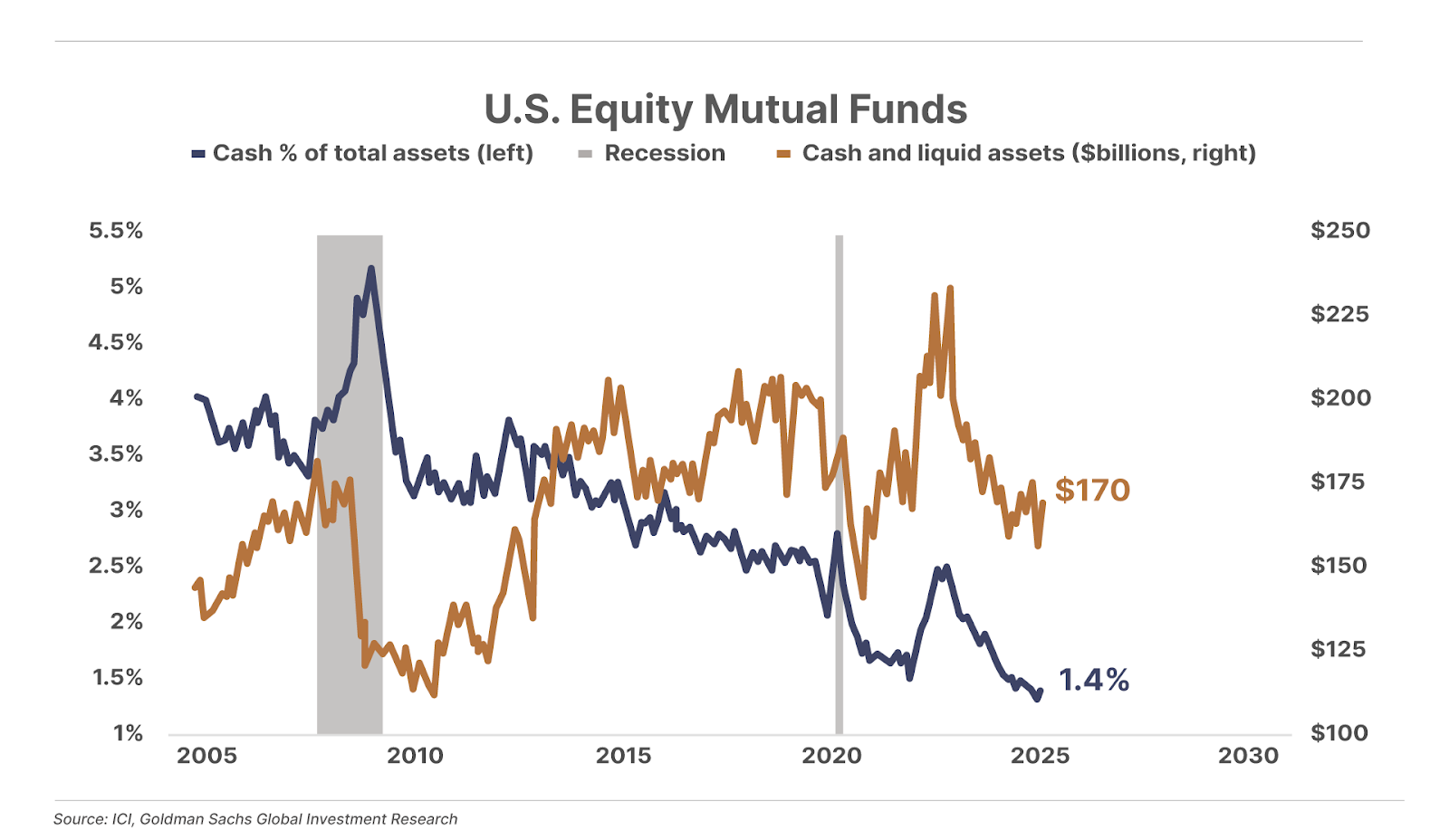

In 1972 – the year before the crash – average mutual fund cash levels shrank to then-record lows of just 4.2% cash invested, reflecting an extremely high level of manager confidence (10% or more of assets held in reserve historically meant fund managers were in a bearish mood).

Managers in 1972 were ultra-bullish. And then came the big drop.

Between January 1973 and December 1974 – triggered by President Richard Nixon’s dollar devaluation and the 1973 oil crisis – the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 45% in its seventh-worst bear market in history. It was the worst loss since the mass carnage of the Great Depression.

In 1972, Mates dropped to 456th place in the mutual-fund performance derby as his fund lost 8.76% of asset value, Neuwirth’s fell to 477th place, and Ehlers’ shuttered completely after its assets under management dropped from $100 million to $20 million.

Ultimately, all three of the funds quietly closed up shop or were absorbed into bigger concerns. Today, if you search online for them, you’ll find that records have been all but scrubbed from the internet.

As for the three erstwhile star managers, they all ended up as far-flung exiles (in Neuwirth’s case, flung far from the wreckage of his whirly bird)…

What’s remarkable – or scary – is that large fund managers have a history of being wrong about exactly this scenario… over and over again.

In both directions, no less.

When fund managers are overinvested and overconfident, with very little cash on hand, watch for a downturn shortly. When they’re overly bearish, you can expect a bull market on the way. In 1951, for instance, managers panicked and set aside a record 15% of cash – and stock gains spent the next decade growing at a breakneck pace of 16.4% annually.

In 1998, by contrast, cash levels dipped down to 4.8%, their lowest point since the 1972 debacle. Managers clearly expected a continued boost in stocks. What happened next? The dot-com crash.

Why are fund managers consistently wrong about the direction of the markets? It’s likely a combination of factors… Like all investors, managers can fall victim to any number of cognitive biases that can lead them astray. But herd mentality is particularly common. There’s a perverse incentive in institutional investing where there’s far less career risk in going along with the crowd – regardless of the outcome – than in taking a divergent position.

In any case, mutual fund cash levels have historically been one of the best measures of long-term investor sentiment and a reliable contrarian indicator… one that’s still well worth tracking today.

And right now, asset managers are holding their lowest levels of cash in history – at just 1.4% of total assets.

In other words, institutional money managers as a group have never been more convinced that stocks will continue to go higher.

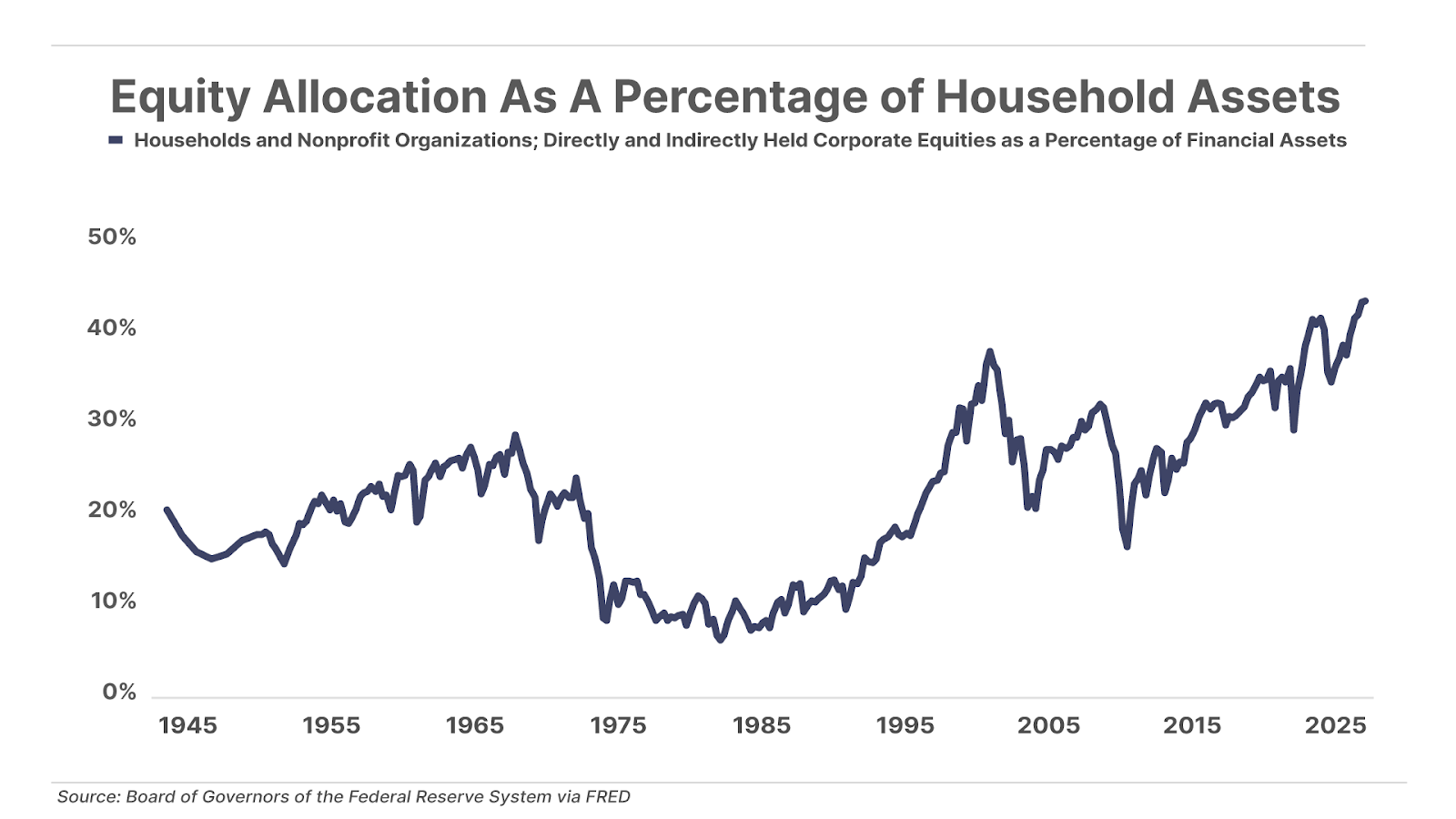

U.S. households are also holding a record 44% of their wealth in stocks, suggesting retail investors similarly see nothing but “blue skies” for the market ahead.

Which means we should be expecting the opposite.

But that’s not the only worrisome extreme that we’re seeing…

U.S. Markets Are Wildly Overvalued

You’ve likely heard that the broad market is expensive right now. But you may not appreciate just how extreme several key valuation metrics have become.

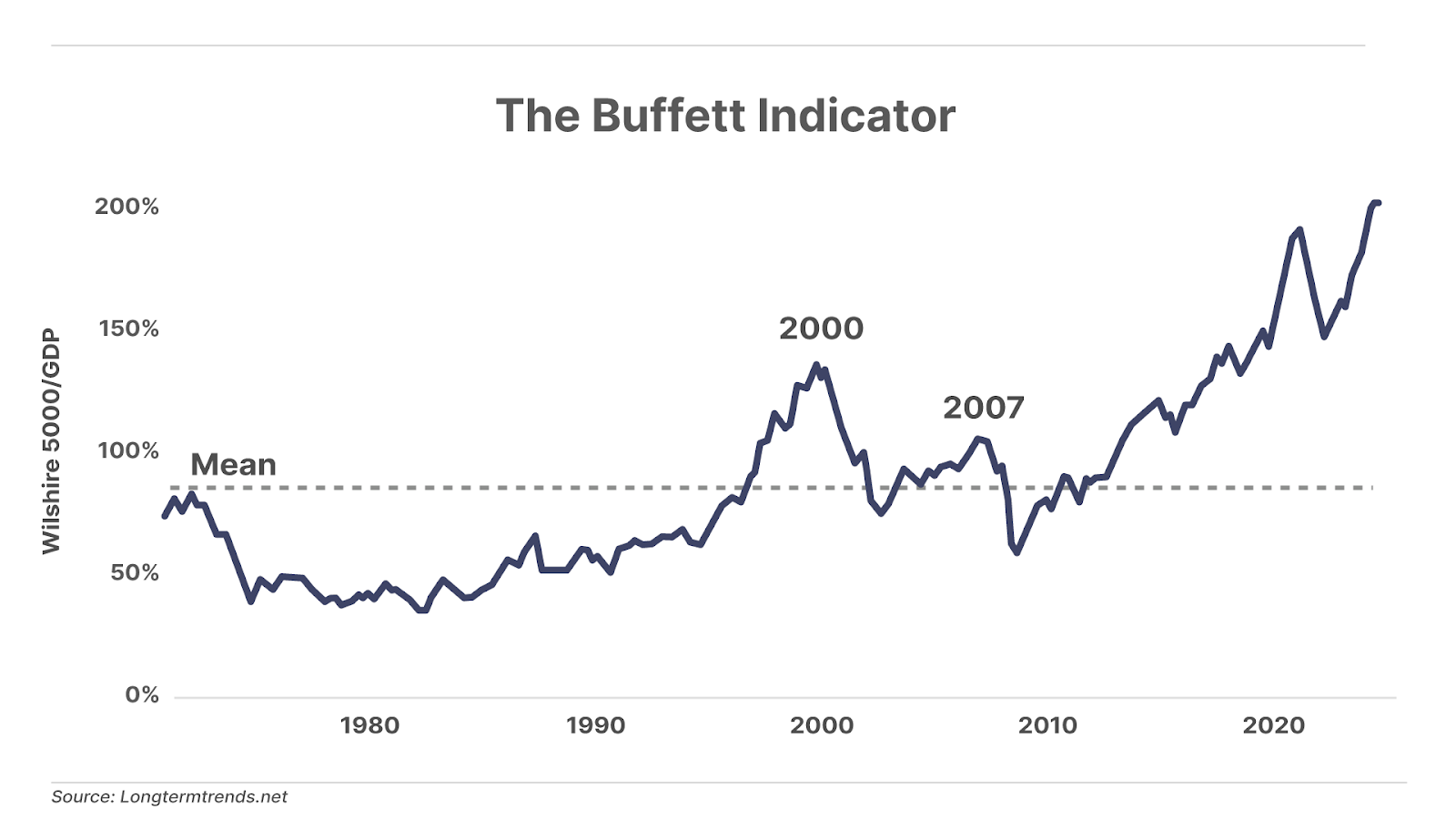

For example, the Buffett Indicator – Warren Buffett’s favorite valuation metric, which compares the market cap of the broad Wilshire 5000 index to U.S. gross domestic product (“GDP”) – now sits at just under 200%.

Said differently, the U.S. stock market currently trades at two times the total value of all the goods and services produced in the U.S. each year.

This is the highest level in the history of the indicator, dating back to 1974 – the year the Wilshire 5000 was launched – and is roughly 40% higher than the previous record set at the peak of the dot-com bubble in 2000.

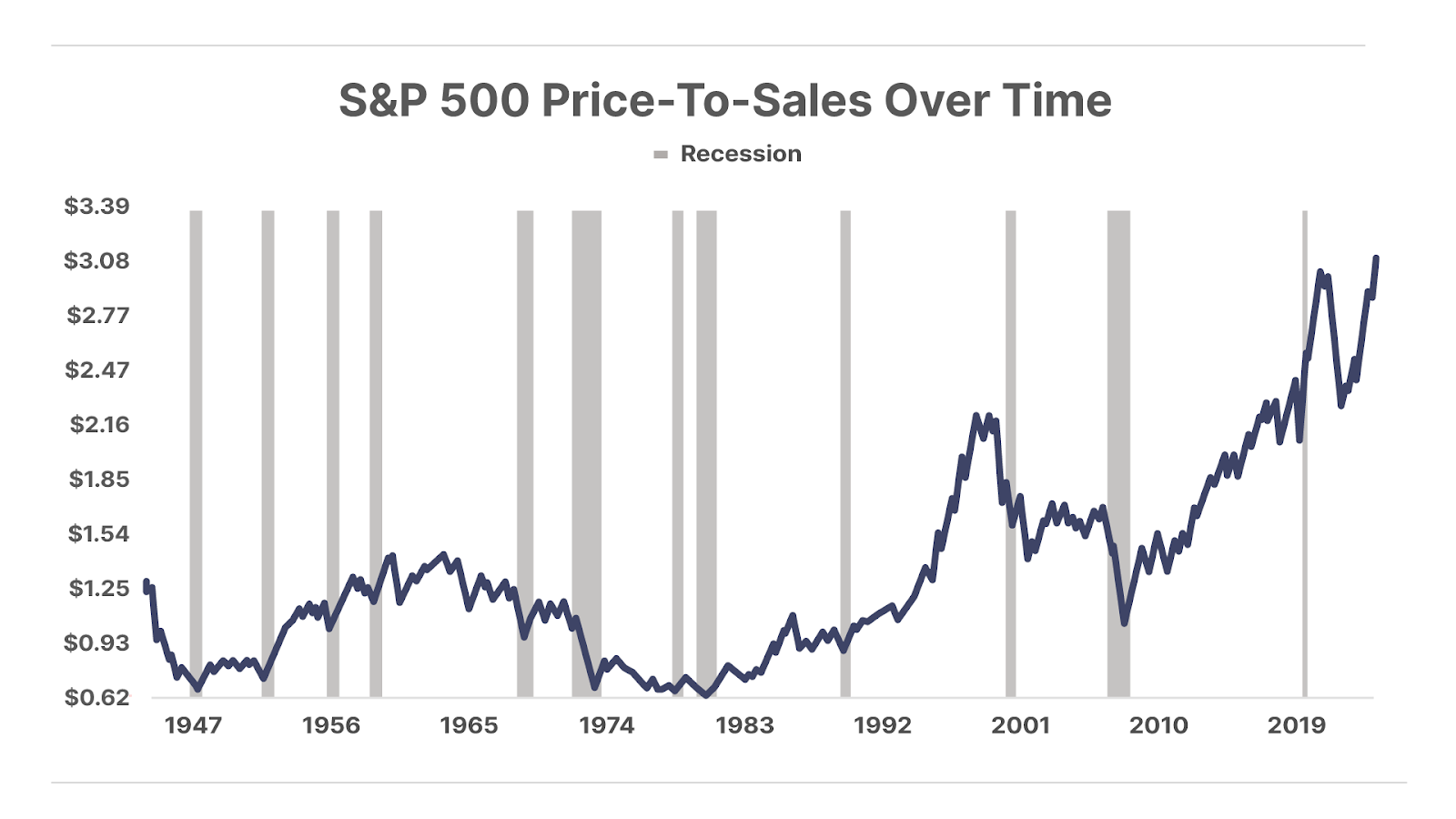

The S&P 500’s price-to-sales ratio is similarly stretched. It’s currently trading above 3 for the first time in history – which is also roughly 40% higher than its previous extreme in early 2000.

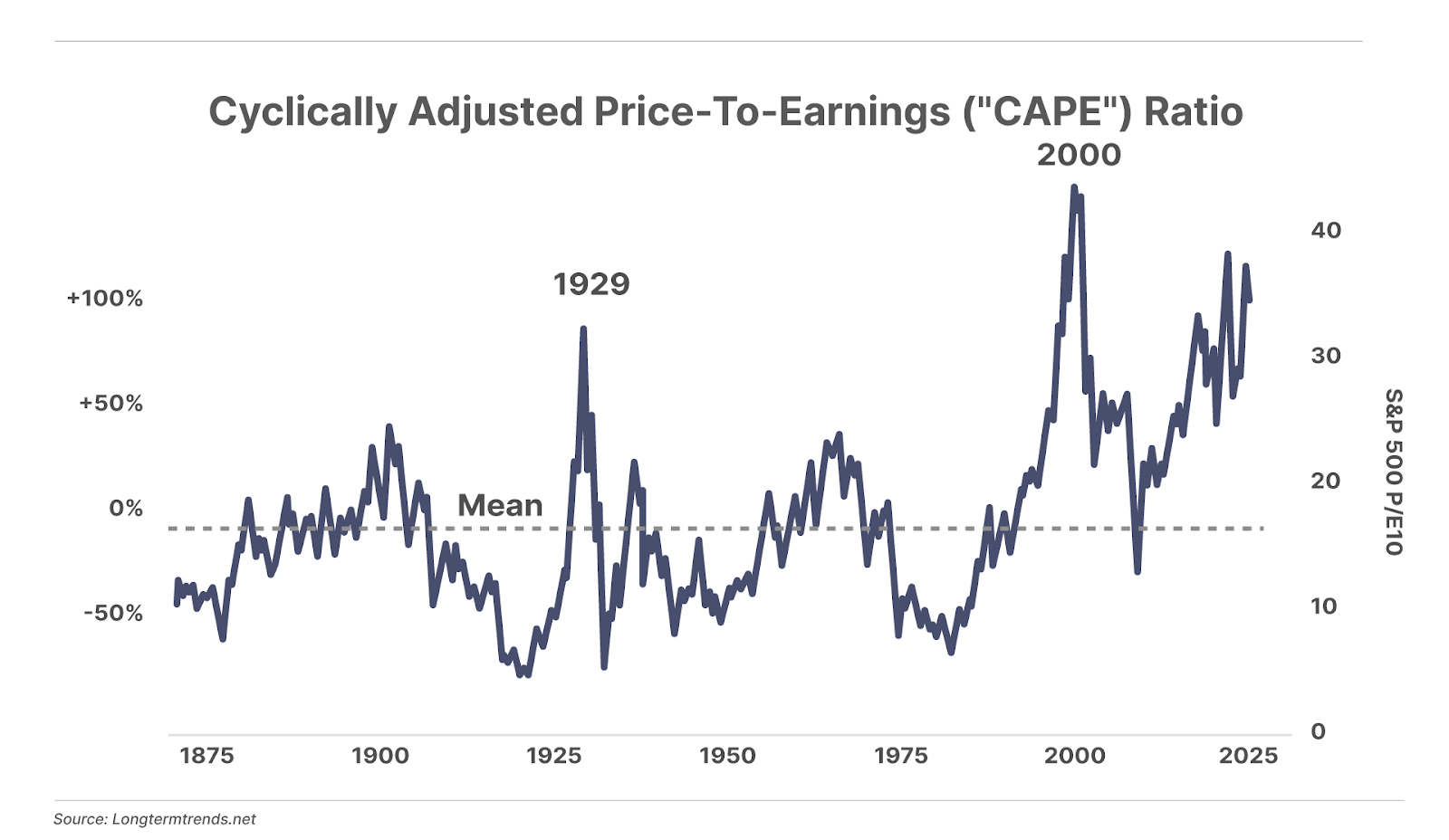

Stocks are also trading at historic extremes relative to earnings. The S&P 500’s cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (“CAPE”) ratio – which uses the market’s average inflation-adjusted earnings over the prior 10 years to smooth out short-term earnings “noise” – is currently around 35.

While this is shy of the all-time record set in 2000, it’s still well above prior bubble extremes in both 1929 and 1965, and more than double the long-term mean dating back to 1865.

Most notably, combining these broad-market measures, along with a handful of others – including traditional trailing and forward price-to-earnings (“P/E”) ratios, price-to-book (“P/B”), enterprise value-to-earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (“EV/EBITDA”), and the Q ratio, which compares a company’s market value to the replacement cost of its assets – produces a valuation in excess of all prior extremes in history.

Stocks Have a Long Way To Fall In A Real Bear Market

While sentiment and valuation extremes like these are reliable contrarian signals – signaling a directional change to come in the market – they are not precise timing indicators. Change could come at any time… and these extremes can sometimes persist for years before they finally “matter.”

However, we are confident that sooner or later, they will matter – just as they always have in the past – and both sentiment and valuations will reset much lower.

So, how far could stocks fall? It’s impossible to know for certain, but we can make some educated guesses.

As you can see in the chart of the CAPE ratio above (currently at 35), since 2000, major market selloffs have seen this ratio bottom somewhere between 15 and 25, around one to three years after the peak on average.

Assuming earnings remained static, a CAPE of 25 – similar to where stocks bottomed during the COVID-19 crash – would put the S&P 500 at 4,100, or about 30% below its current level of 5,700.

At the lower end of the range, with a CAPE of 15 – roughly where stocks bottomed during the Global Financial Crisis – the S&P would trade below 2,500, a decline of nearly 60% from current levels.

Of course, we would also expect earnings to slow during a major market decline, which would bring the 10-year average of inflation-adjusted earnings down as well. In that case, stocks would need to fall more than the above estimates to account for that.

We suspect not many of today’s exuberant investors are prepared to weather a 30% to 60% drop over the next few years… and unfortunately, it’s possible that could be an optimistic view.

Why? Take another look at the CAPE ratio above. You’ll notice that prior to the “easy money” (low-interest-rate) era of the past few decades, major market declines tended to bottom at significantly lower valuations than they have recently. In fact, prior to the 1990s, it was rare to see the market bottom at a CAPE above 10.

For example, at the end of the inflationary bear market of the 1970s, the S&P 500’s CAPE ratio fell to 7. A similar valuation today would bring the S&P 500 to 1,140, a decline of 80% from current prices.

At the 1932 Great Depression low in stocks, the market traded at a CAPE of just 5.5. That would put the S&P 500 at 895, a decline of nearly 85%.

Even worse, investors had to wait up to 25 years for stocks to return to new highs after these declines. By the time they were over, many investors had sworn off investing in stocks ever again.

Now, we’re not predicting this kind of worst-case scenario will happen. Fact is, the federal government (or Federal Reserve) has intervened in every major market decline since the 1990s. And we don’t expect that to change.

But we also believe that most equity investors are greatly underestimating the potential range of outcomes that are possible in the years ahead.

Hope For The Best, Prepare For The Worst

Again, we can’t know for certain when these extremes will “matter,” only that they eventually will. And when they do, investors who are heavily invested in overpriced equities could be wiped out.

If you hope to avoid that fate – and be among the relative few who are able to take advantage of the generational buying opportunities that are likely to arise – you must prepare now.

This is why we continue to recommend that Porter & Co. readers remain extremely conservative today.

Stay patient. Be sure to hold plenty of cash. And keep the bulk of your equity portfolio in the highest-quality companies trading at reasonable prices… or better yet, consider investing in an asset – like distressed bonds – that can generate equity-like returns with far less risk.

As you’ve probably seen by now, Porter recently released a video about how buying distressed bonds is providing him with a Second Life in investing. If he had it to do all over again, he says, he might avoid stocks entirely. In his presentation, he talks about how bonds – particularly the right bonds – are the investment world’s best-kept secret. They offer a high level of security, superb returns, and significantly less volatility than stocks. You can watch his presentation right here.

If you’re interested in exploring high yield bonds as an alternative to buying stocks right now, we are offering a special price on our bond research until midnight tonight… call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447, for more information on getting access.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.