America’s Next Great Energy Success Story

An Innovative Way Of Getting LNG To Market

| Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at: [email protected]. Paid subscribers can also access this issue as a PDF on the “Issues & Updates” page here. |

If you weren’t living under a rock in the 1990s, you likely remember Nicole Brown Simpson’s last plate of rigatoni.

Simpson – the ex-wife of pro football legend O.J. Simpson – polished off the fateful dish of noodles on a June evening in 1994, at a Los Angeles Italian restaurant called Mezzaluna. Post-pasta, a Mezzaluna waiter, Ron Goldman, who’d been “just friends” with Nicole for a few months, took it upon himself to deliver a forgotten pair of glasses back to her nearby condo.

Just after midnight, Simpson and Goldman were both found stabbed to death outside the condo, along with a bloody glove that matched one belonging to Nicole’s jealous ex-husband, O.J.

The double homicide led to a famously televised, low-speed car chase in a white Ford Bronco, the most publicized murder trial in history, and O.J. Simpson’s ultimate acquittal (in the eyes of the law, anyway… the court of public opinion was widely divided on the matter).

Less widely-known is what happened to the restaurant where it all started… Mezzaluna.

Before the ink was dry on the “Simpson Surrenders After Freeway Chase” headlines, looky-loos crammed into the little Italian eatery to pilfer silverware and napkins as keepsakes. As O.J.’s trial progressed, a flock of “Guilty” signs festooned the trees and railings outside the restaurant, while a stream of 5,000 tour buses a day crawled past so thrillseekers could ogle the site of Nicole’s last meal.

By the time the eight-month-long trial was over, Mezzaluna’s owner – a non-Italian Lebanese-Egyptian immigrant named Charif Souki – had had enough of what he called “lack of taste and decency.” He sold the beleaguered restaurant, auctioned off anything not nailed down, and looked for a new line of work.

For no particular reason – other than, maybe, the fact that it was as far from the restaurant business as possible – he decided to join the liquefied natural gas (“LNG”) industry.

That fateful choice would lead to Souki’s brief tenure as America’s highest-paid CEO, a dramatic downfall (twice!), and ultimately, a smear of egg on the face for Porter & Co.

It would also give us a painfully clear blueprint for how not to invest in LNG – and what to do instead…

Cheniere-Death Experience

Souki had an MBA in finance, and before his foray into the restaurant industry, he’d spent a decade as an investment banker, jetting between the Middle East and Wall Street. He still had plenty of deep-pocketed contacts, and it didn’t take him long to drum up $2 billion. He planned to build an LNG import facility on the Louisiana-Texas border – ready to receive and process shipments of gas from far-off energy hubs like Qatar.

He called it Cheniere Energy (LNG) – and he built it at exactly the wrong time.

In 2008, just as the Cheniere import facility neared completion, fracking technology hit the big time – meaning that America could produce enough of its own gas not to need to rely on other countries’ energy anymore. That, of course, was bad news for facilities designed to import gas. At the ribbon-cutting event for Cheniere, investors pointedly ignored the ceremony to watch LNG shares hit lows of 95 cents (down from $21) via the real-time tickers on their BlackBerries (also a new technology at the time!).

Souki quickly pivoted to a new strategy: flipping Cheniere from an import to an export facility. U.S.-based frackers would bring their product to Souki, who’d liquefy it for transport, and ship it overseas. It was a total overhaul that would require another $20 billion, from investors who hadn’t yet seen a dime from their initial $2 billion.

Souki – an extraordinary salesman – was able to pull it off, and did an about-face. Over the next few years, Cheniere would become the only export facility on the United States mainland, shipping millions of tons of LNG to energy-hungry China, Japan, and South Korea. By 2013, Cheniere was an $18 billion company, and Souki himself was America’s highest-paid CEO, bringing home $142 million a year.

The good times (for Souki, anyway) lasted barely two years. In 2015, Souki found himself on the outs with activist investor Carl Icahn, who owned a 13.8% stake in Cheniere and wanted to focus on returning dividends to investors – while Souki wanted to use any extra cash to build a second facility. With the board on Icahn’s side, Souki was ousted from his plummy CEO position, and retreated to his estate in Aspen, Colorado.

If Icahn wouldn’t let him expand, Souki decided, he’d build bigger, better, faster on his own. In 2016, he started building an export terminal on the Louisiana site that Icahn’s board had nixed – only this one would be an even more ambitious project than Cheniere.

Souki’s new company, Tellurian (TELL, which went public in 2017) wouldn’t just process gas from other fracking companies… TELL would frack its own, from the ground up, and then turn it into LNG and ship it overseas. In other words, Souki planned to build the first fully integrated (gas field, gas pipeline) LNG facility in the United States and use it to ship out a targeted 27.6 million tons of LNG annually – twice Cheniere’s annual exports at the time.

It was a massive project… too massive, as it turned out.

And it would ultimately spell Charif Souki’s second (or, counting Mezzaluna, his third) undoing.

Too Big To Shale

Tellurian’s business plan (which Souki called the “Driftwood Project”) started out on solid ground – gaseous ground, that is.

Souki bought 11,060 acres in the Haynesville Shale in northern Louisiana, including working interests in 78 producing wells. By 2021 those wells produced 39 million cubic feet of gas a day, and revenue was a little over $70 million, up about $20 million from the year before, thanks to higher gas prices. Souki had long-term purchase agreements lined up with major clients in Singapore and the Netherlands, as well as global oil major Shell.

And that’s where we, at Porter & Co., came in.

We thought Tellurian’s mega-build-out was a great idea – so much so that we recommended it in one of our earliest issues of The Big Secret, in June 2022. Porter wrote then that Driftwood was “the exact same LNG-export business I would build…. Buy the gas in the ground, cheaply. Build the pipeline to get the gas to the coast. Build the LNG terminal to sell it to the world.” Simple, right?

Turned out, not so straightforward.

The ambitious, and expensive, infrastructure buildout – the fracking, processing, and liquefaction equipment – that stalled, and ultimately tanked Charif Souki’s second bid for gas and glory.

The traditional industry approach to building LNG terminals – the one Souki used – is known as the “stick-built” method. The large-scale liquefaction trains – the workhorses of an LNG terminal used to cool and compress natural gas into LNG – are custom manufactured on site from the ground up, by hundreds of construction workers and engineers.

Phase 1 of the Driftwood Project – four phases were planned in all – involved two of these massive “stick-built” trains, including – just as one example – 20,000 piles driven into the ground. By 2023 – five years after the start of construction – only 9,000 of those phase 1 piles had been hammered into the Haynesville Shale.

Driftwood’s multi-layered complex was a lot easier to build in Souki’s head – and one by one, financiers and foreign clients dropped out of the project as construction deadlines got pushed further and further back.

By September 2022 Tellurian had lost its last major backer, Shell, and had unsuccessfully tried to raise capital via a last-ditch $1 billion bond offering. At year-end 2022, the company reported a net loss of $49.8 million – and in 2023, it tripled that loss to $166 million. By the end of Q1 2024, management acknowledged that there was “substantial doubt about our ability to continue as a going concern.”

In July 2024, Tellurian gave up the ghost and sold out to Woodside Energy, an Australian energy company, for $1 a share.

To be fair, we’d foreseen the possibility of something like this happening back when we made our initial recommendation and assigned it our highest-level risk rating of 5… We wrote:

There are all kinds of things that can go wrong – and this is a very small stock. It has a market cap of just over $2 billion. Its share price is going to be extremely volatile. Moves up of 100% or more won’t be unusual. And moves down of 50% or more won’t be either. On average, the shares are 100% more volatile than the Nasdaq, so please don’t buy this deal if you aren’t comfortable with a lot of volatility.

Likewise, this is the kind of situation where if something goes badly wrong, you can lose all of your money. I don’t think that’s going to happen, but it isn’t out of the question.”

It wasn’t out of the question for Charif Souki. He was booted from his CEO role at Tellurian in December 2023, got himself into $99 million in debt, and lost his TELL shares and his treasured yacht, Tango, to the Swiss bank UBS. He also lost his Aspen, Colorado, mansion in a forced sale, leaving him, he lamented in his bankruptcy filing, “homeless.” (However, he acknowledged outside the filing that he has “other properties around the world,” so we suspect that reports of his distress are somewhat exaggerated.)

There are plenty of directions for Charif Souki to go next… he might even open a restaurant.

For us (and other unfortunate TELL investors), our next move was clear. We sold the stock in October 2024 at a 74% loss.

It was a painful reminder – for us, and for many other investors – that in the complex world of LNG, bigger is not always better.

Our next recommendation of a company that has taken the polar opposite approach. It has specifically designed its LNG terminals using small-scale equipment that can be built in dedicated manufacturing facilities, and then shipped to the project site for easy, low-cost, and fast construction. It used this approach to build the two fastest-ever constructed LNG terminals in American history, and it’s already generated $18 billion in revenue from its first three years of producing LNG.

But the real upside for this business lies in its aggressive expansion plans, and the way that it has positioned itself to profit from the coming supercycle in LNG prices.

The Coming Global Gas Supply Shortage

LNG is the super-chilled version of natural gas that shrinks down to 1/600th of its original size after it’s cooled to negative 260 degrees Fahrenheit. This ultra-compact form of natural gas can then be loaded and shipped via specially designed LNG tanker ships, enabling the export of natural gas to countries around the world.

Over the next 25 years, global natural-gas demand is projected to increase by 30% from 155 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) last year to 200 Tcf (a unit that measures the volume of gas) by 2050. And the share of gas demand coming from LNG will increase from 13% of the total to 19%, translating into 89% growth in LNG demand over the same 25-year period.

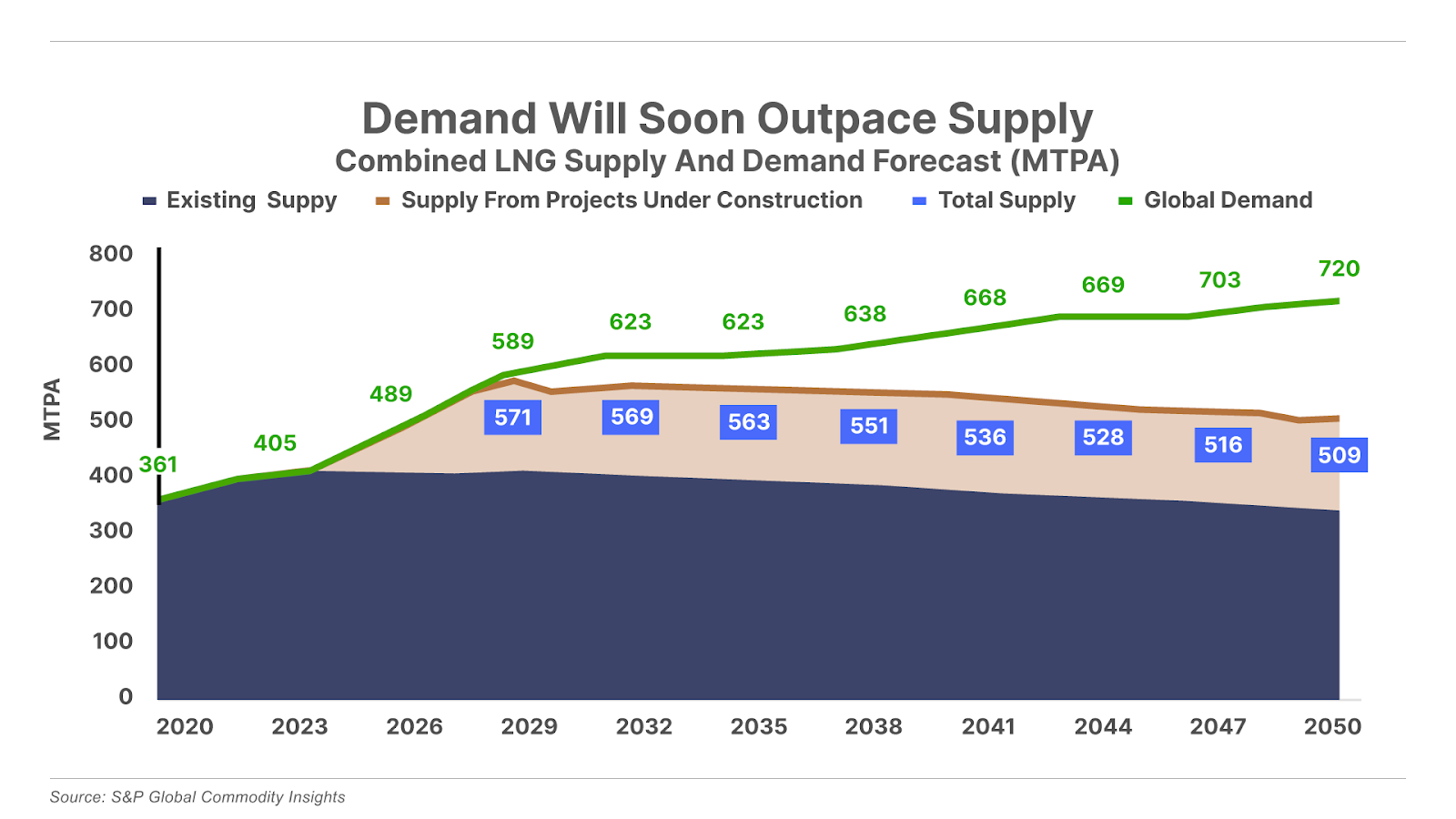

The problem – and the opportunity – is that LNG supply growth is on pace to significantly fall short of the increase in demand. A recent analysis from commodities and financial research firm S&P Global forecasts that LNG supply will begin falling short of demand by 2030, leading to a global LNG deficit that will reach 110 million tons per annum (MTPA) by 2040 and 211 MTPA by 2050, as shown below (while Tcf measures the volume of gas, MTPA measures the level of annual supply and demand):

Many factors contribute to this looming supply deficit, but mainly it is a lack of investment. And, as Porter recently explained on X, this lack of investment can be traced to one of mankind’s greatest delusions: that the world must stop investing in fossil fuels in order to prevent the end of civilization as we know it:

For years, the world’s leading energy-forecasting agencies have contributed to the false promise that “green” energy sources, like wind and solar, would replace hydrocarbon fuels, like LNG. Consider the case of the International Energy Agency (“IEA”), a leading authority in global energy-supply and demand forecasting. Over the past two decades, IEA’s forecasts for LNG demand have underestimated actual demand by an average of 41% per year.

As a result, the global economy is woefully unprepared to meet the coming surge in LNG demand. And addressing it won’t be easy, cheap or quick. Bringing an LNG facility from idea to fruition requires $10 billion to $40 billion in capital, depending on the size of the facility, with the typical payback period being decades, not years.

After a company decides to build an LNG exporting terminal, known as the “announcement date,” it must then find billions in financing commitments to reach the final investment decision stage – when developers and investors formally commit to proceeding with construction. Then comes the most challenging part: building the project, including navigating the immense governmental and environmental regulatory hurdles.

When everything goes according to plan, proceeding from the announcement phase to shipping cargo requires six to eight years. But, as happens with many large-scale LNG projects, things inevitably go wrong and timelines can get pushed out beyond a decade.

Consider the case of the $40 billion LNG Canada project in British Columbia, owned by a consortium including Shell, PetroChina, Mitsubishi, and Korea Gas. When the project was announced in 2018, it was expected to come online within eight years. But after a series of operational and permitting delays, that timeline has grown to 14 years, to 2032. Similarly long delays have plagued the Golden Pass LNG terminal in Sabine Pass, Texas, owned by ExxonMobil and Qatar Energy.

Since time is money, the present value of projected future cash flows for these projects takes a major hit when timelines get extended. As a result, the economics have turned out to be far less compelling than originally forecast. This, in turn, creates an even bigger hurdle for new projects to secure the investment capital.

For all of these reasons, a future LNG shortage is all but guaranteed. There simply isn’t enough investment going into new LNG projects to meet the huge coming demand. And any new announced projects likely wouldn’t come online until the mid 2030s, at the earliest.

But with every crisis comes opportunity. We’ve found the ultimate LNG business model suited to fill this supply gap. Unlike its peers, plagued by project delays, this company has brought its first two LNG terminals online in just two and a half years – the two fastest LNG projects ever built in the U.S.

The company’s secret lies in its construction approach that allows it to build projects faster than its top rivals, leading to faster cash flow generation, and therefore higher returns on invested capital. This rapid pace of cash returns enables the company to reinvest in aggressive growth, which could make it one of the largest LNG exporters in the world within the next decade, based on its current plans. And there’s also a feature within this business model that could make It one of the biggest winners from the coming LNG shortage set to hit the market in the 2030s and beyond.

The Ultimate Way To Play The Coming LNG Supercycle

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.