For the past several months here at Porter & Co., we’ve urged long-term investors to be cautious. We continue to believe a severe economic contraction is approaching. But that doesn’t stop us from finding shorter-term bullish opportunities.

Promising Short-Term Trends Won’t Save Us From The Big Crash

Our Long-Term Market Plan Is Still Unchanged…

In preparation for the upcoming launch of our new website, we are retiring the publication name “Something You Don’t Know.” You’ll still receive an email with great content from us every Friday… but now, it will all appear under Porter’s flagship Big Secret on Wall Street letterhead.

You don’t need to do anything… and nothing will change except for the name of the publication.

This is “Toadzilla” – the largest documented “cane toad.” She’s the size of a football and weighs in at a hefty 6 lbs. She can eat hundreds of smaller creatures a day (insects, or anything else that fits in her enormous mouth) and kill a dog the size of a beagle with her toxic venom.

She and her millions of invasive brethren are rapidly taking over the continent of Australia.

It all started innocently enough…

Arthur Bell, a plant pathologist at Australia’s Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations, had the best of intentions.

It was the early 1930s. Bell and his colleagues in the eastern state of Queensland had been tasked with solving the country’s cane-beetle problem.

Sugar had bankrolled Queensland – and grown to be a vital part of Australia’s economy – since Captain Louis Hope raised the first successful sugar cane crop on the state’s eastern coast in 1862. But by the turn of the century, the industry was on the verge of crashing from its “sugar high.”

Sugar cane isn’t native to Australia, and it isn’t a natural fit with the continent’s rugged climate. Drought, in particular, was often a problem. But the biggest challenge was the larvae of two native species of beetles – collectively known as “cane beetles” – that had a voracious appetite for the roots of the sugar cane plant.

Pressured by cane farmers who were fed up with decades of chewed-up crops, the Queensland government in 1900 established the Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations to find a solution.

Unfortunately, this was easier said than done. Adult cane beetles have a tough shell (or “exoskeleton”) and bury their eggs deep under the soil, making them relatively difficult to kill. Effective insecticides were still decades away.

By the time Arthur Bell came along, the Bureau had spent the better part of 30 years experimenting with crude chemical pesticides – including arsenic, copper, and petroleum-based pitch, among others – with limited success.

But Bell had a different idea.

In 1932, he attended a sugar industry conference in Puerto Rico. While there, he learned the Puerto Ricans had apparently solved a similar problem with a novel approach: they had imported a species of toad from Central America that preyed on beetles in their native habitat.

He returned to Queensland with a thought: Perhaps this strategy could work for Australia as well?

Despite the clear risks of introducing a new species to the Australian ecosystem, Bell’s idea gained the support of his colleagues and fellow scientists over the next couple of years.

So in mid-1935, just over 100 “cane toads” were introduced to the small town of Gordonvale, Queensland, near the northeastern coast of Australia.

Within months, this population had grown into the thousands, and the Bureau was ready to begin its real-life experiment. In August, it released roughly 2,400 toads in sugar plantations near Gordonvale. Over the next two years it would ultimately release nearly 60,000 more in surrounding areas.

The Toads Bite Back

Australia’s cane toad experiment was initially hailed as a potential savior of the sugar industry. But it would ultimately be known as a colossal blunder… because the introduction of cane toads triggered catastrophic unintended consequences across the Australian ecosystem.

First, the toads didn’t actually eat many of these beetles. Turned out, they often couldn’t reach the subterranean-dwelling insects.

Also, Aussie cane beetles and cane toads work “opposite shifts.” The toads are primarily active at night. Yet unlike Puerto Rico’s nocturnal species of cane beetle, Australia’s native beetles are generally active during the day. The toads also can’t hop to the tops of six- to eight-meter sugar cane stalks, where these adult beetles like to feed.

So instead of snacking on Australia’s cane beetles, the cane toads ate just about everything else.

And they aren’t picky. They’ll consume any critter they can fit in their mouths, including all types of insects, snails, other toads, frogs, and tadpoles, rodents, snakes, small lizards, and more. Their ecumenical approach to “what’s for dinner” led to significant declines in the populations of many native fauna (including natural predators of cane beetles).

They also competed with native frogs and toads for food and resources, where their large size, aggressive nature, and reproductive prowess gave them a tremendous advantage. Cane toads can mate year-round, and can lay up to 60,000 eggs a year (versus the 1,000 to 2,000 eggs typical of Australia’s native frogs), and reach maturity faster. They can also live for up to 15 years, giving them lots of time to wreak havoc.

What’s worse, the toads poisoned many of the country’s larger animals.

Few of Australia’s native predators (or pets!) have resistance to the deadly toxins these toads secrete as a defense mechanism. (The average adult toad contains enough toxin to kill a medium-sized dog within 15 minutes.)

That meant that the ripple effect of the cane toads also resulted in declines in the populations of animals further up the food chain, including birds, turtles, large snakes and lizards, marsupials, and even crocodiles.

Overall, the toads have been like Godzilla for the natural ecosystem. They’ve proven to be an even more difficult pest to control than the cane beetle itself. The roughly 60,000 toads released near Gordonvale have grown to a population of more than 200 million, stretching across nearly a third of the country today.

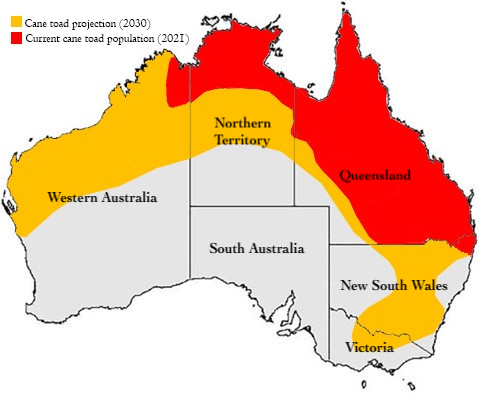

Cane toads can now be found in most of Queensland, in more than a third of the Northern Territory, and in parts of Western Australia and New South Wales. And they continue to migrate at a rate of up to 40 miles per year. At that rate, they’re expected to inhabit almost half of the continent by the end of this decade.

Ultimately, toads could cover the entire continent. As the Australian government itself has admitted, “there is unlikely to ever be a broadscale method to control toads across [our country.]”

The Australian cane toad debacle is a classic example of a situation that looked promising in the short term, but that ultimately ended in disaster.

We see a similar dynamic happening in markets today – minus the toxic toads and cane sugar.

Clearing Up Some Confusion

For the past several months here at Porter & Co., we’ve urged long-term investors to be cautious. We’ve recommended being extremely selective with new investments because we continue to believe a severe economic contraction is approaching – one that’s likely to create once-in-a-generation opportunities to buy world-class assets (including both stocks and distressed bonds) at fire-sale prices.

Yet, as readers of our new Porter & Co. Wealth Signals service may have noticed, our colleague Scott Garliss has been unabashedly bullish on both stocks and bonds of late.

This has understandably led to some confusion among readers… Have we suddenly changed our minds about the likelihood of a big economic slowdown? Do we no longer expect The Greatest Legal Transfer of Wealth in History? Or are we speaking out both sides of our collective mouths?

The answer, of course, is none of the above. This apparent contradiction is simply a matter of perspective.

You see, unlike our investment research services (The Big Secret on Wall Street, Distressed Investing, and more to come), Porter & Co. Wealth Signals is a macro-focused trading service. It’s meant to help readers navigate (and profit) from relatively short-term moves in various asset classes.

For example, since launching his service just shy of one month ago, Scott has cited a number of reasons he believed the broad stock market would move higher in the near term, including extreme speculative short positioning in the futures markets, a likely peak in short-term interest rates, and falling inflation.

Those calls have been spot-on so far, with the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite Indexes rising roughly 5% and 8%, respectively, with Scott’s recommendations also moving up.

Scott thinks that those tailwinds could continue to push the broad markets higher over the next few months, at least.

He could well be right. Despite clear signs of excess surrounding artificial intelligence, the recent rally has shown no signs of stopping.

Here in The Big Secret, our aim is simply to buy great businesses whenever we’re able to do so at a fair price.

But this doesn’t mean we ignore “macro” entirely.

The fact is, roughly once every decade or so – typically as a result of some combination of unsustainable debt levels and central bank tightening, as well as other factors – the credit cycle turns, the economy slows, and even the greatest businesses can briefly trade at rock-bottom prices. These rare periods offer patient, conservative investors the opportunity to build truly life-changing wealth.

Given the historic excesses we’ve witnessed in the debt markets over the past decade – and the unprecedented tightening by central banks in the past year – we believe the next turn in the credit cycle is likely to be one for the record books.

And while we can’t know exactly when trouble will arrive, we remain confident that – not unlike Australia’s failed experiment with the cane toad – today’s short-term gains will ultimately give way to longer-term pain.

H.O.P.E. Spells Pessimism

Analysts track dozens of so-called “leading” indicators to forecast where the economy is headed. These include widely followed measures like the U.S. Treasury yield curve and consumer sentiment, as well as less familiar metrics like credit spreads and industrial production.

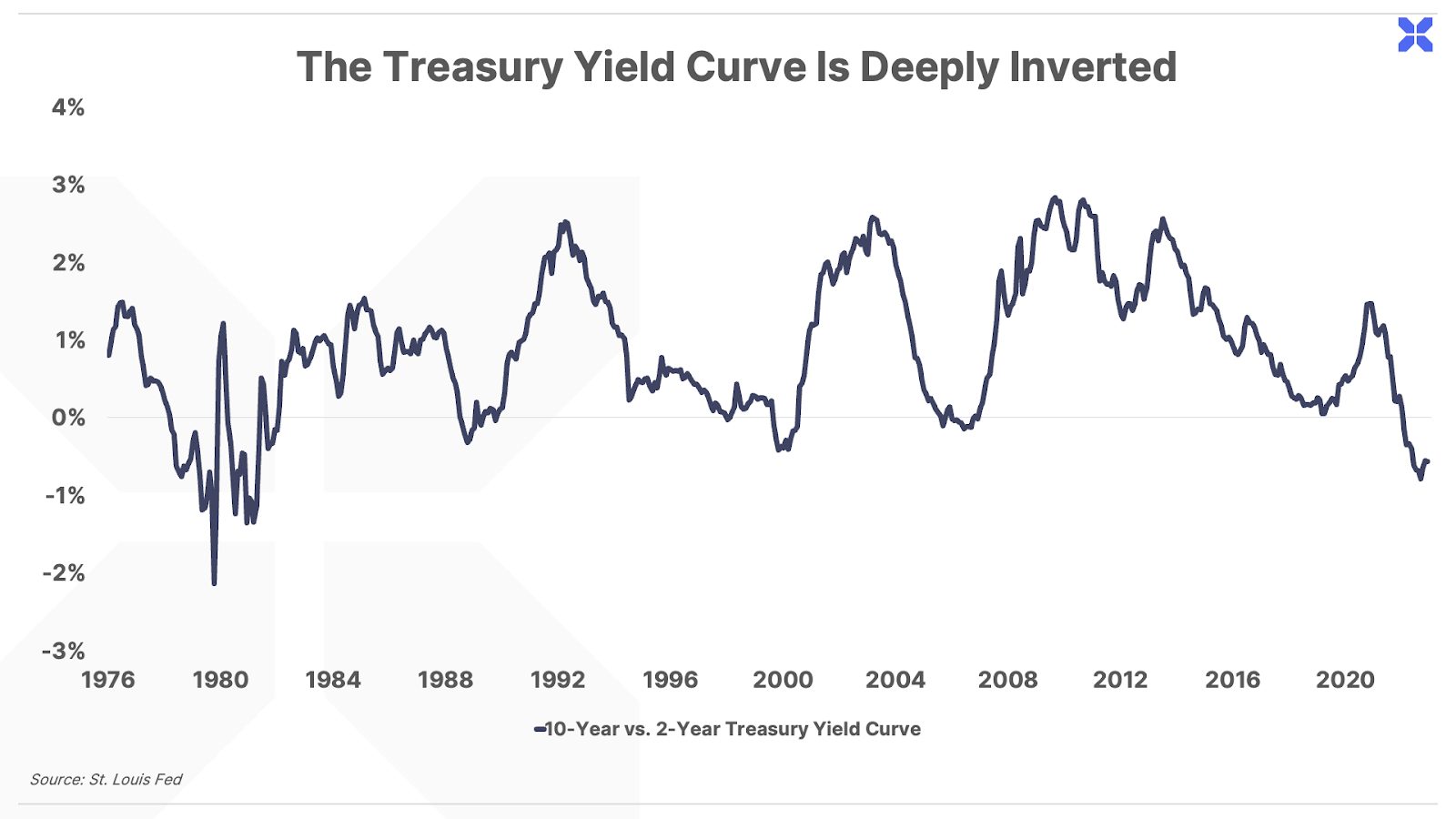

Some individual indicators – such as yield curve “inversions” in particular – have a solid track record of predicting economic trouble. However, these indicators tend to be most useful when considered in combination with others.

One of the simplest and most reliable frameworks we’ve come across is the “HOPE” model, coined by Michael Kantrowitz, the chief investment strategist at brokerage Piper Sandler.

HOPE stands for Housing, Orders, Profits, and Employment – indicating the predictable path that weakness takes as it works its way through the economy.

Because the housing industry relies so heavily on mortgage financing, it’s among the most interest rate–sensitive areas of the economy. As a result, it is typically the first place that economic weakness appears… often two years or more before an official recession begins.

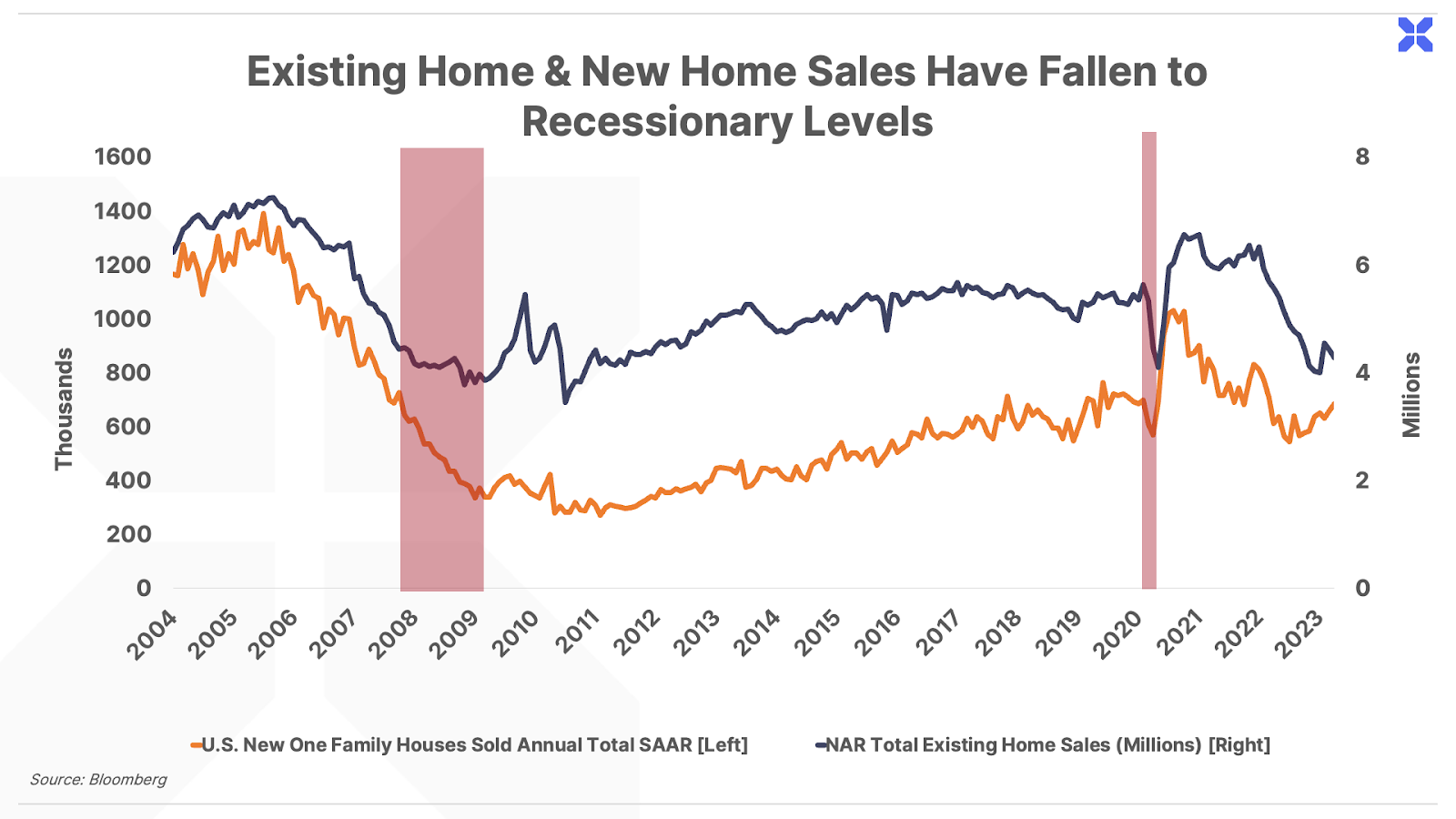

As you can see below, both new and existing home sales peaked nearly three years ago – in August and October 2020, respectively – and have already fallen to levels consistent with recessions in the past.

Falling homebuilder sentiment – as tracked by the National Association of Homebuilders – is another reliable tell. It topped out in November 2020 and has also fallen to recessionary levels to date.

After housing, weakness typically begins to spread to the manufacturing sector, as companies begin to pull back on new orders in response to rising inventories.

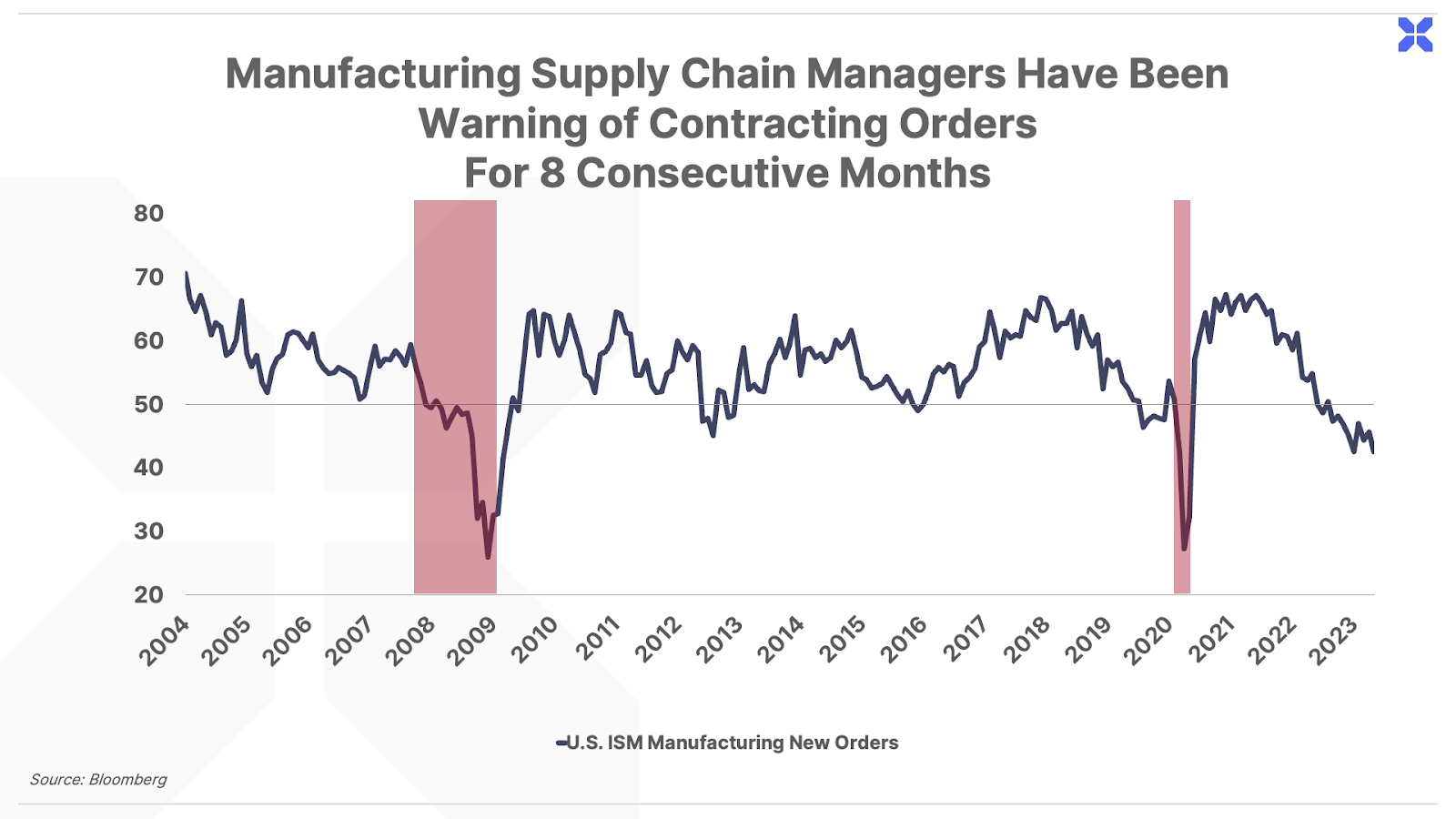

One of the best leading indicators of this trend is the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index. Each month, the ISM surveys supply chain managers on whether various aspects of their businesses – including new orders – are expanding, contracting, or stable. It then sums up the results, with figures above 50 representing expansion and those below 50 representing contraction.

As you can see below, the ISM Manufacturing New Orders Index peaked in early 2021, dropped below 50 last summer, and has fallen deeper into contraction for eight consecutive months. It, too, is now well into territory that has preceded recessions in the past.

Weakness in the ISM New Orders Index predictably leads to actual weakness in the manufacturing sector a few months later, and that’s exactly what we’ve seen.

Manufacturers’ new orders peaked shortly after the ISM entered contraction last summer.

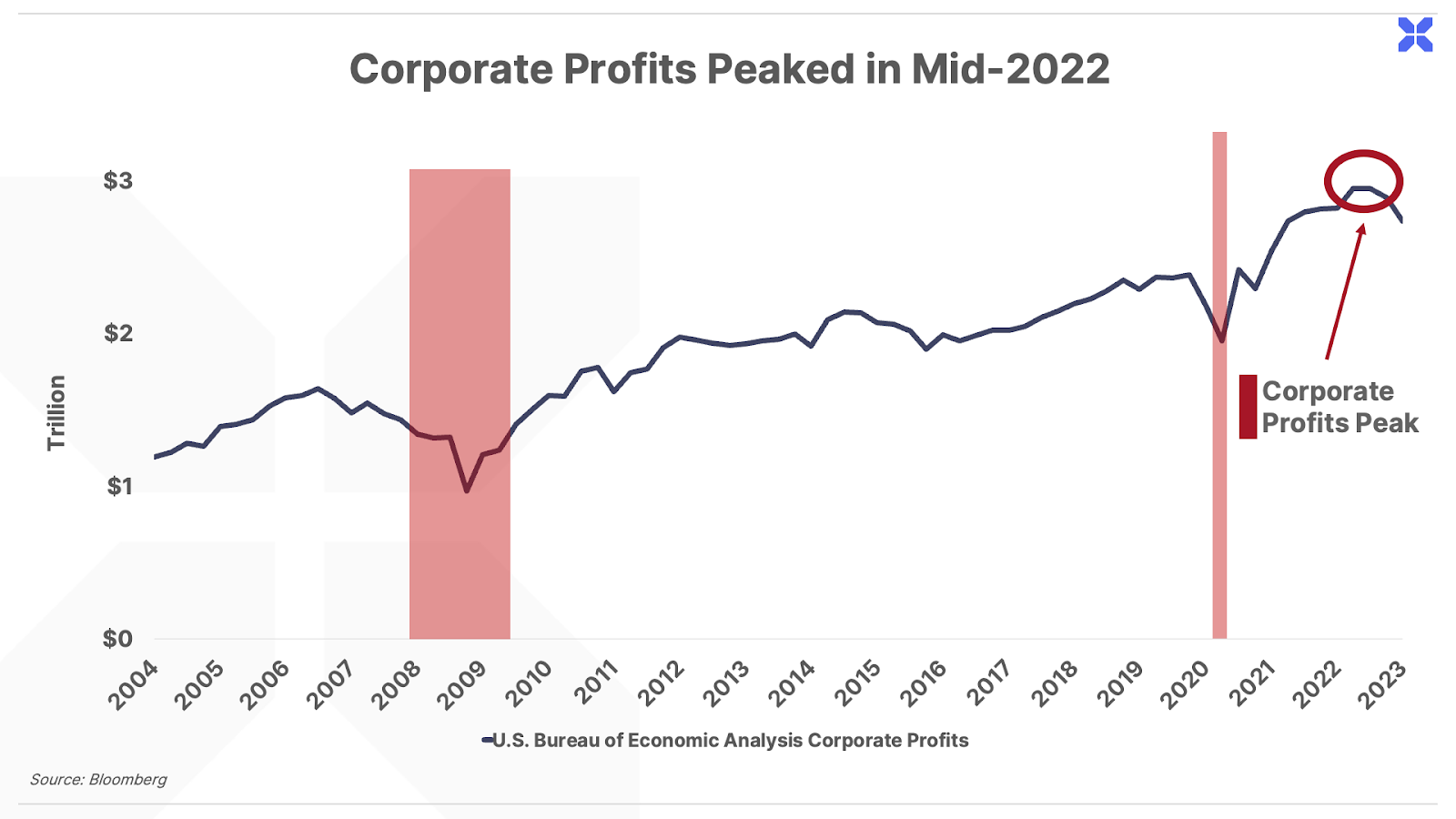

Declining new orders ultimately show up as lower corporate profits.

Contrary to headlines of “better than expected” first-quarter earnings, the reality is that average company earnings have been declining for the better part of a year.

As you can see below, broad corporate profits peaked last summer, and S&P 500 earnings per share growth has been negative for two consecutive quarters.

Finally, falling profits ultimately begin to weigh on employment, as companies exhaust other cost-cutting measures and are forced to lay off employees.

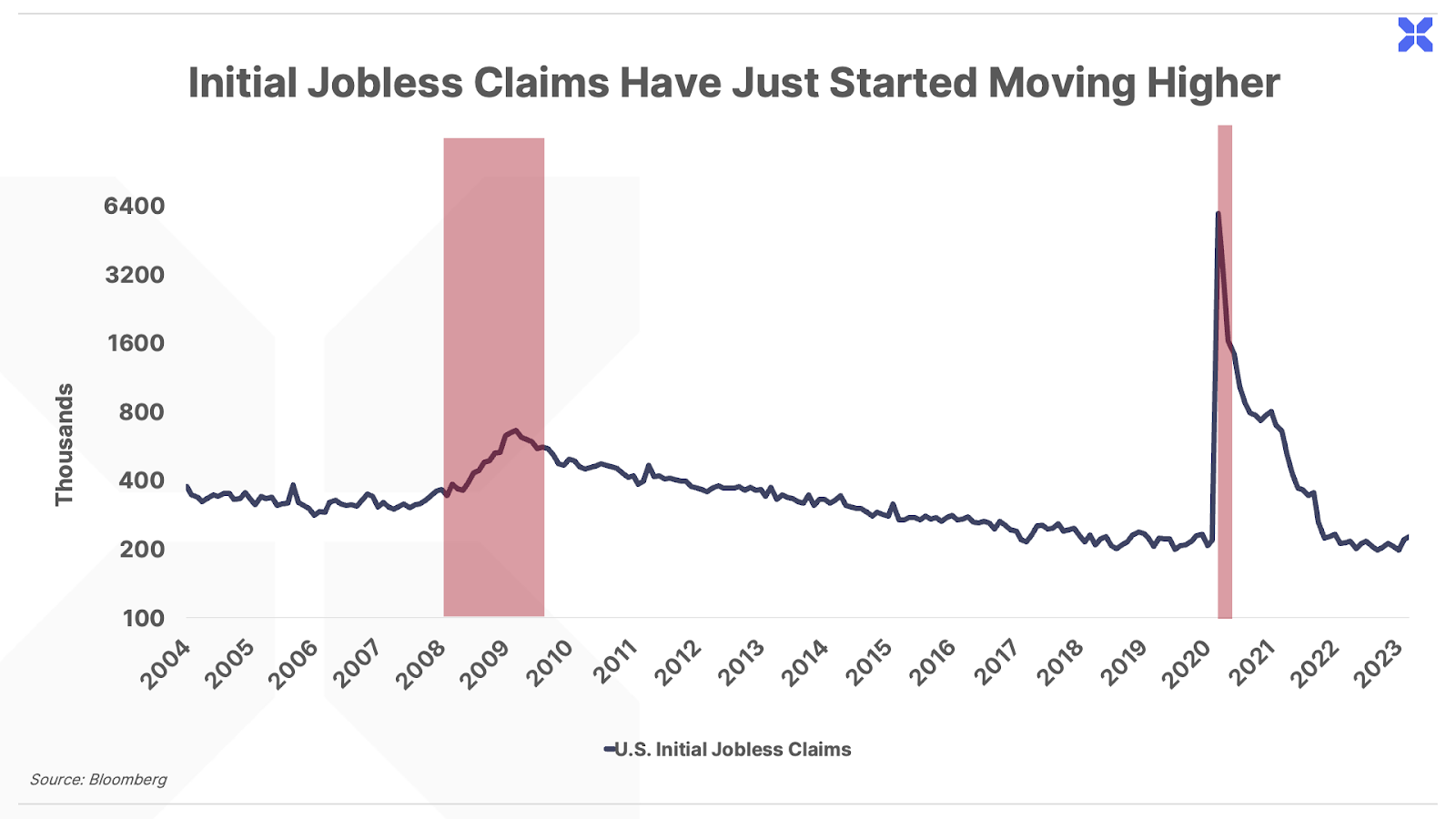

This typically appears first as rising initial jobless claims that eventually cause a sharp rise in unemployment.

Today, the official unemployment rate remains near historic lows at just 3.7%. But in just the past few months, we’ve begun to see initial jobless claims move higher, jumping to a fresh 18-month high in May.

This Time Is Not Different

In short, folks betting on a “soft landing” (or “no landing”) for the economy are likely to be disappointed. The HOPE cycle is currently progressing exactly as it usually does ahead of a recession.

Housing and orders have already fallen into recession territory, profits appear to have peaked, and unemployment is just beginning to tick higher.

Of course, these HOPE metrics aren’t the only signs of impending economic trouble we’ve been tracking in recent months.

One of the most reliable is the Treasury yield curve. As we’ve mentioned, the yield curve has “inverted” – that is, long-duration Treasury yields have fallen below short-duration yields – prior to every recession since World War II.

It’s currently among the most inverted it’s ever been in history.

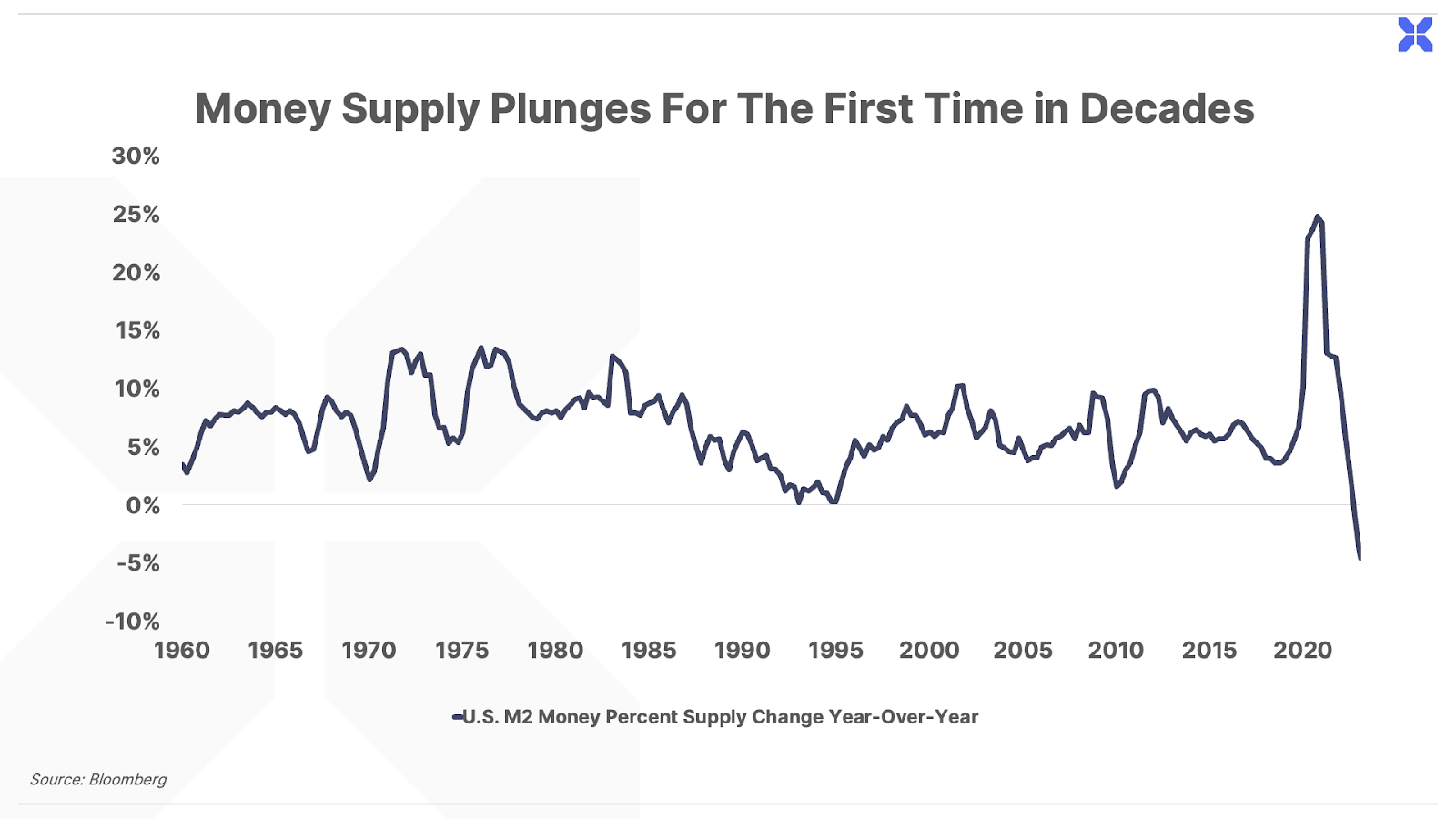

We’ve also noted that M2 – a measure of broad money supply – has been contracting for the first time since the Great Depression. This is a huge problem for America’s debt-based economy, which requires an ever-expanding supply of new money to function.

Historically, when money supply growth merely slows, the economy grinds to a halt. We shudder to think what a prolonged contraction could mean.

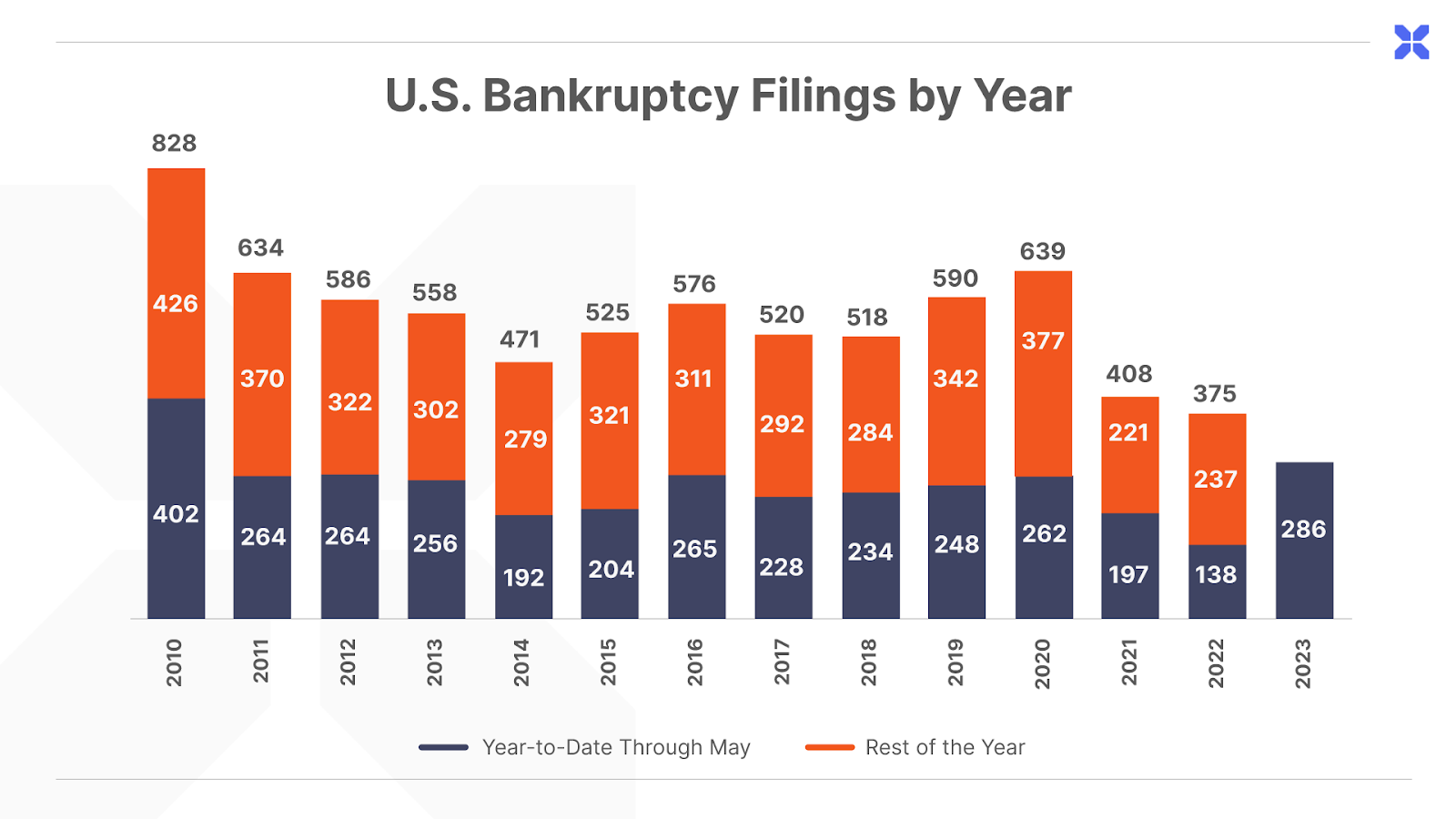

U.S. bankruptcy filings are also rising sharply. At 286 in the year-to-date through May, they’re currently on pace for their worst year since the end of the Great Financial Crisis in 2010.

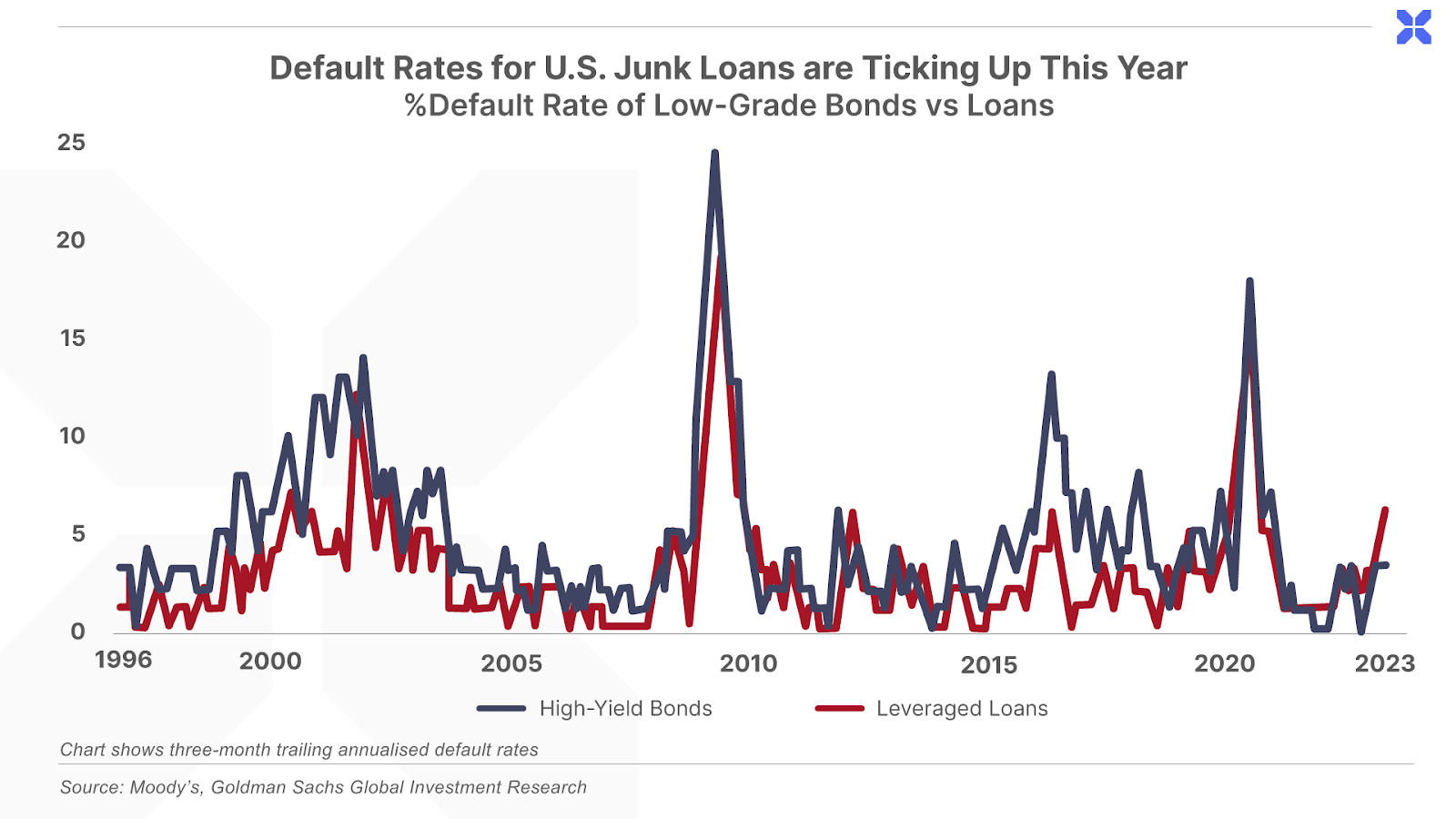

And we’re now beginning to see signs of stress in the high-yield debt markets, as well.

The default rate on leveraged loans has risen to its highest level since 2009 (not including the Covid lockdowns). History suggests junk bond defaults are likely to follow.

Unless we begin to see a significant improvement in these metrics, it’s likely just a matter of time before a serious slowdown arrives. To expect otherwise is simply wishful thinking.

The (Speculative) Calm Before the Storm

Given these recessionary smoke signals, you may be surprised the markets – and stocks in particular – have been performing so well recently. But this isn’t unusual either.

While stocks are generally forward-looking, they tend to have a “blind spot” when it comes to recessions. According to investment research firm 42 Macro, the broad market historically peaks at roughly the same time the unemployment rate begins to rise.

In other words, stocks don’t typically begin to price in a recession until the “E” in HOPE begins to deteriorate meaningfully.

That hasn’t happened yet, which means the recent rally could easily continue. It’s possible that markets could even reach new highs before it ends.

But again, barring a significant improvement in the indicators above, this wouldn’t diminish the risks of a severe downturn.

The bottom line is that we believe successfully navigating today’s market is ultimately a question of time frame and strategy.

Skillful traders could do very well riding this speculative rally. (Just be sure to have an exit strategy, as Scott reminded readers this morning!) But we continue to believe long-term investors would be wise to remain patient and conservative for now.

A financial reckoning appears inevitable.

And unlike Australia’s ongoing nightmare with the cane toad, these troubles are likely to create tremendous opportunities for investors with the foresight (and capital) to take advantage.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. Porter & Co. Wealth Signals is currently available for FREE to all Porter & Co. readers for one more week. After June 23, it will be available only to paid-up subscribers and Partner Pass members. If you haven’t had the opportunity to read it, be sure to check it out here.