This 100+ Year Old Lindy Business Will Create An Unbreakable Legacy Of Wealth

This is Porter & Co.’s Complete Investor (formerly The Big Secret On Wall Street), our flagship publication that we publish every Thursday at 4 pm ET. We regularly provide to our paid-up subscribers a full report on a stock recommendation, and also an extensive review of the current portfolio… At the end of this week’s issue, paid-up subscribers can find our Top 3 Best Buys, three current portfolio picks that are at an attractive buy price.

Every week in Complete Investor, we provide analysis for non-paid subscribers. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, to access the full paid issue, the portfolio, and all of our Complete Investor insights and recommendations, please click here.

This is it.

This month’s recommendation is one of the few, genuinely elite businesses in the entire world. And not one of you has ever heard of it – because it didn’t exist a year ago.

I have no doubt the report on this company will prove to be the best recommendation of my entire career – surpassing even The Hershey Company (HSY), Microsoft (MSFT), and W.R. Berkley (WRB).

I urge you to please read this entire issue, above all others, carefully. It’s no exaggeration to say that what follows could, all by itself, build a fortune for your family. A fortune that will last 100 years… or more.

I’ve been writing investment research since 1996 – nearly 30 years. In my entire career I’ve never – not once – seen a better investment idea. Nothing else even comes close.

But I know most of you (maybe even all of you) will dismiss this idea out of hand. It doesn’t fit into any of the preconceived notions about investing that the media (CNBC) and Wall Street have sold you. You – virtually all of you – will say: oh, this isn’t for me. There’s not enough upside. I don’t have five years to wait. I need something that’s going to make me rich sooner.

Make no mistake, this investment idea isn’t going to make you rich in a day. I don’t gamble. Or guess. I’m only interested in investments that I know – that I’m virtually certain will appreciate. And over any realistic time frame – five to seven years, at least – this investment will far outperform the market. If you’re wise enough to make this one of your foundational holdings, it will also outperform every other business in the S&P 500 over the next 25 years. And longer.

My fear is that most of you simply won’t recognize what this is…

A Business That Will Compound Forever

Let’s start here.

Do you know which public company has produced the most profit for investors in the history of America’s capital markets?

Long-time readers know that’s Philip Morris. A single dollar invested in Philip Morris in the 1920s would have grown into millions by today. No other business comes close to this track record of lasting wealth. Philip Morris earned its investors about 16% a year for more than 100 years. That’s about twice as much as the stock market’s annual average.

Most of my subscribers know and understand Philip Morris’s exceptional economics. But… do you know who #2 is – a company that has outperformed all of the others, except Philip Morris, since the 1950s?

I doubt you’d ever guess. I’ve never seen this company advertise or watched its CEO on CNBC. It isn’t a capital-light business. It isn’t a consumer-brand business. It doesn’t trade in high-value commodities, like oil. And it isn’t a technology company – it’s the opposite. There’s hardly a less tech-centric business in the world.

It trades in rocks. Not ore. Not rocks with minerals embedded. Just plain rocks: aggregate – meaning granular materials like sand, gravel, and crushed stone.

It’s called Vulcan Materials (VMC). It traces its roots to 1909, when Irish immigrant William F. Vulcan founded the Birmingham Slag Company in Alabama. Vulcan figured out how to turn an industrial waste product – steel mill waste – into road-building material. He took what no one wanted and made it useful, constructing roads across the South as the automotive boom transformed America.

By the 1950s, Vulcan’s company evolved into a dominant regional aggregate business by merging with Lambert Brothers in 1956 to form Vulcan Materials. This greatly expanded Vulcan’s key asset: its quarry network. Further acquisitions, like Union Chemicals in 1961 and dozens more, built a one-of-kind moat: aggregate mines.

Aggregate mines combine geological scarcity with regulatory barriers, making effective competition virtually impossible. Today, no major U.S. quarry is approved without about 10 years of litigation, which typically costs $20 million or more. And if you’re building practically anything, you need aggregate that’s local – the cost to transport stones and gravel (because of their extreme weight) limits shipping to under 50 miles. If you need rocks in Indiana, you’ve got to mine the rocks in Indiana.

Over more than eight decades, Vulcan Materials built America’s largest network of aggregate mines. Its one-of-kind network of aggregate mines enables Vulcan to set the price of the material in virtually every major U.S. market. That translates into annual price hikes, year after year, even through recessions.

While it might not look like much compared to glamorous businesses, Vulcan boasts exceptionally high, 28% operating margins and virtually perpetual revenue growth. That creates incredible, long-term results for investors.

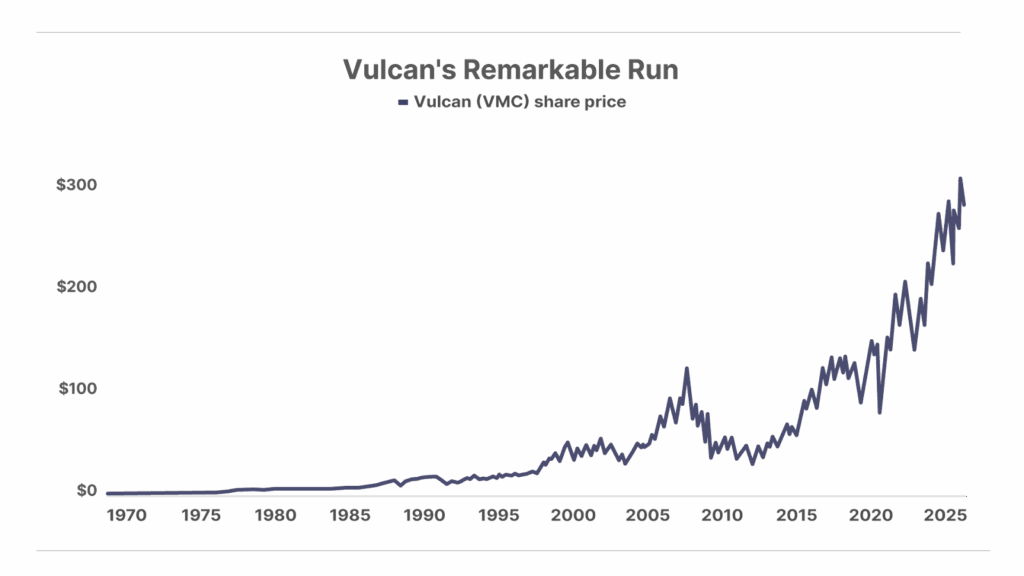

Going back to 1980, shares of Vulcan have delivered 15.4% annualized returns for at least 45 years. Further academic research shows it has delivered those same returns (15%+) for almost 70 years.

Investors in Vulcan have discovered a holy grail. The company is like an ATM machine that spits out money, year after year, no matter what. That’s why it trades at 30x to 40x earnings. It’s a great business, but shares are too expensive – it’s trading at such a high price that future returns are unlikely to be market beating.

Don’t worry, though. There’s a far better investment in rocks available today. It’s a company that’s far larger, that’s far older, and that has a far better business model. It also has the very best management team in the building-materials industry.

And this is a company no one has ever heard of – nobody.

Porter, that’s impossible!”

But it’s not.

When A Company Does This, Run Away

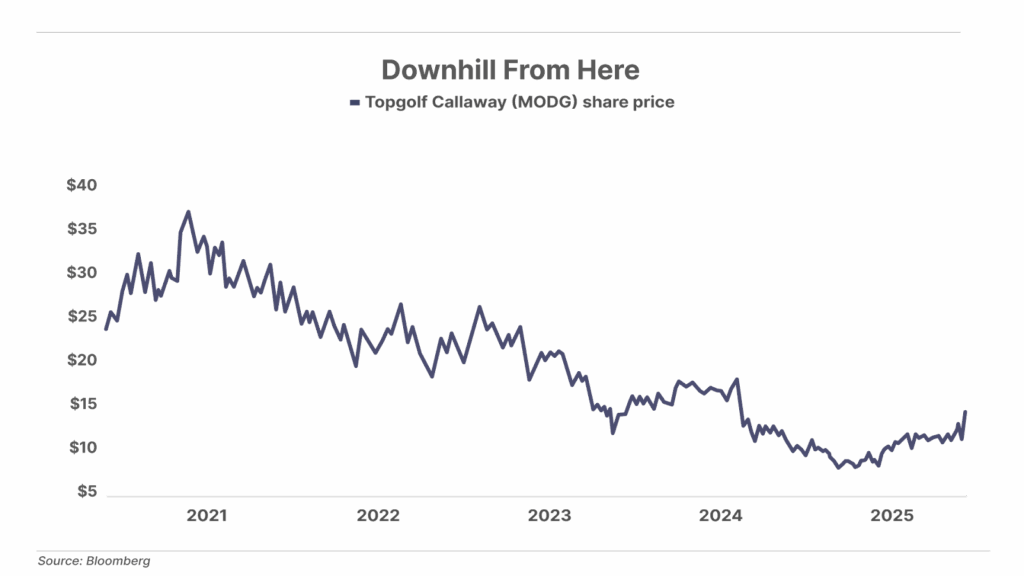

On November 15, 2025, word began to leak that Topgolf Callaway (MODG), formerly just Callaway Golf, is in talks to sell Topgolf – which combines a golf driving range with dining and entertainment.

Callaway is trying to unwind a $2.1 billion merger just four years after it closed. It’s selling the Topgolf business at a valuation that’s half its original price. As a result, Callaway shareholders have lost more than $1 billion of enterprise value.

From day one, the deal was a dumpster fire: after the merger was announced Callaway’s shares plunged 19%. Abandon ship!

Baruch Lev and Feng Gu wrote the definitive guide to understanding why so many big corporate mergers and acquisitions fail: The M&A Failure Trap: Why Most Mergers And Acquisitions Fail And How The Few Succeed (Wiley Finance, 2024).

This deal raised every single red flag:

- Unrelated businesses (golf equipment versus entertainment and hospitality)

- Paid for with stock, diluting shareholders

- Oversized relative to the acquirer – the deal cost exceeded Callaway’s $1.9 billion market cap)

- Massive leverage – Callaway assumed $555 million in net debt, sending its annual interest expenses up 82%

- Acquiring a financially distressed business (Topgolf’s earnings nosedived from $105 million in 2018 to negative $1.3 million in 2020 amid COVID closures

On a post-deal conference call, Callaway CEO Chip Brewer lamented unforeseen challenges, like the soaring cost of chicken wings. Those are risks that no other consumer golf-brand CEO (or his shareholders) must manage. Beyond the word golf, the two companies had zero operational overlap. “Combining them made no sense,” said Forbes.

So why did it happen?

The same reason all these deals happen: there’s nothing but upside for the acquiring management team – with more assets to manage, their bonuses and salaries grow – and there are huge fees for the bankers.

As Warren Buffett explained:

Investment bankers, being paid as they are for action, constantly urge acquirers to pay 20% to 50% premiums over market price for publicly held businesses. The bankers tell the buyer that the premium is justified for “control value” and for the wonderful things that are going to happen once the acquirer’s CEO takes charge. What acquisition-hungry manager will challenge that assertion?”

Inevitably these perverse incentives drive horrible results for shareholders.

German automaker Daimler-Benz’s $36 billion acquisition of Chrysler in 1998 promised “a perfect fit of two leaders in their respective markets,” according to the bankers. But the deal delivered $30 billion in value destruction before Daimler-Benz unloaded Chrysler for only $7.4 billion in 2007. A $28 billion disaster.

Bank of America’s (BAC) $2.5 billion “buy the dip” purchase of lending company Countrywide in 2008, amid the subprime meltdown, cost $40 billion in settlements and write-downs by 2012. Another disaster.

Even smaller deals frequently fail.

eBay’s (EBAY) $2.6 billion purchase of Skype in 2005 never panned out. The online auction company unloaded the internet phone service for $1.9 billion in 2009 – a $700 million loss. Quaker Oats’ $1.7 billion Snapple drinks deal in 1994 flopped, leading to a $300 million sale in 1997 – a $1.4 billion write-off. Microsoft’s $7.2 billion Nokia acquisition in 2014 (remember that one?) led to a $7.6 billion write-off in 2015. Total loss.

And then there’s the most infamous corporate “whoops” of all time: TimeWarner and AOL’s 2000 merger, which cost TimeWarner shareholders around $70 billion by the time the company was broken up in 2009. Coda to that deal: In 2018, AT&T (T) acquired TimeWarner for $85 billion. It was later spun off with a $43 billion loss in 2022.

Virtually all large-scale corporate M&As fail because these deals allow the acquiring management teams access to enormous amounts of additional capital, without having to actually earn it through organic growth.

What’s this got to do with rocks? Everything.

When A Company Does This, Buy

One of Charlie Munger’s best quips is: “All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.“

It had a deeper meaning. The idea was inversion. Rather than trying to figure out what to do as an investor, it’s often easier to identify what not to do.

If corporate acquisitions destroy investors’ capital, what’s the inverse of those kinds of transactions? What happens when companies make large divestitures, when they spin-off good operations?

In 2013, Abbott Laboratories (ABT) spun off its pharmaceuticals arm as AbbVie (ABBV), a seemingly routine separation of mature diagnostics (Abbott) from high-growth drugs (AbbVie). Critical question: where did the incumbent CEO land? Abbot’s existing CEO, Rick Gonzalez, chose to leave with what’s commonly called the “SpinCo” in these transactions. And in this particular case, the SpinCo was later named AbbVie.

The financial result? AbbVie produced 350% in total return over the next decade, trouncing Abbott’s 225% and the S&P 500’s 180%. Its sales and earnings were propelled by a new drug – Humira – whose sales exceeded $200 billion.

Again, Buffett explains the role of human nature in these corporate machinations:

A few years later, bankers – bearing straight faces – again appear and just as earnestly urge spinning off the earlier acquisition in order to “unlock shareholder value.” Spin-offs, of course, strip the owning company of its purported “control value” without any compensating payment.”

And beyond the bankers’ need for transactions, another driving factor is a CEO’s economic incentives. Having been a CEO of a publicly traded company, I can assure you, it isn’t hard for the CEO to accurately judge which company assets are more likely to appreciate rapidly… and which are about to die. Separating the best sled dogs from the pack and leaving the rest is a logical strategy for an ambitious CEO who’s being handcuffed by a board with important personal ties to the assets that are underperforming.

There are many outstanding academic studies that quantify the real-world outcomes of this legal form of insider trading.

Purdue University’s 1965-2000 study found 10% annualized excess returns from publicly traded SpinCos. S&P Global’s 1998-2016 analysis showed 5.8% annualized outperformance. As more investors realized the opportunity in SpinCos, the available alpha (outperformance) declined, but did not disappear.

Most recently, amid 22 deals over $1 billion, the Bloomberg U.S. Spin-Off Index (BNSPIN) is up 22% year to date (“YTD”) versus the S&P’s 18%.

And when parent executives migrate to the SpinCo – as in 17% of cases – returns are even better. Investment research company DataTrek reports 15% to 20% excess annual returns in such scenarios, per Trivariate Research’s Spin-Offs Investing (April 2024).

Managers, unshackled from a conglomerate’s lower-quality assets, can focus on the company’s best assets, unlocking 13% compound annual revenue growth versus parents’ 8%, per McKinsey’s October 2021 The Power Of Spin-Offs . It’s not hard to understand why this happens: senior managers flee underperforming assets and brands for the conglomerate’s best assets and brands.

And there’s one more thing about SpinCos every investor should understand: at first, they fall in price because institutional investors frequently regard the shares they receive in the SpinCo as a dividend. Those investors, more often than not, sell these extra shares and reinvest the capital in other places. In some cases, institutions must sell the SpinCo because it isn’t (yet) a part of the index that they’re mandated to mirror.

Thus, when these SpinCos first emerge, they’re orphans – they do not yet have a steady base of large institutional shareholders. And, as a result, in the first two to three quarters they typically perform poorly.

I’ve seen this in my career, time after time.

PayPal’s (PYPL) 2015 spin-off from eBay dipped 10% in value in its first quarter as e-commerce investors dumped the fintech orphan, then PayPal shares surged 150% over three years and 400% in six years, fueled by the rise of payment platform Venmo.

GE HealthCare Technologies’ (GEHC) 2023 separation from General Electric fell 5% initially amid industrial rebalancing, then climbed 40% over the last two years on imaging tech demand.

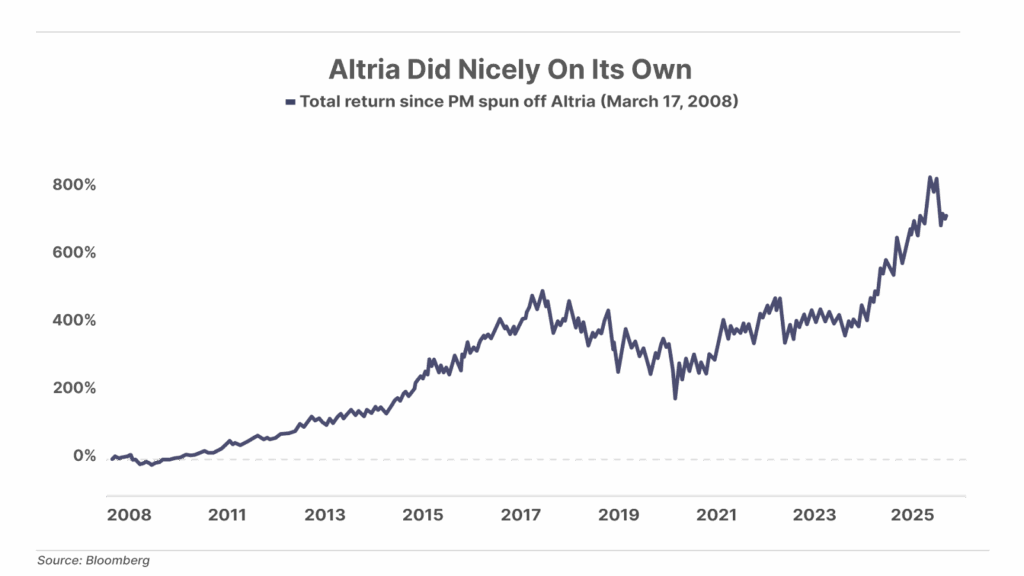

Philip Morris International’s (NYSE: PM) 2008 split from Altria (MO) dropped 15% in its first six months, but delivered 200% gains over four years as international markets boomed.

Even Ferrari’s (RACE) shares fell when they were spun off from Fiat Chrysler in 2016. They tumbled 20% in their first year, then vaulted 400% over the next five.

Otis Worldwide’s (NYSE: OTIS) 2020 split-off from United Technologies fell 15% amid COVID, then doubled over four years on elevator modernization (and now finds a place in the Legal Monopolies section of the Complete Investor portfolio).

And in one of the best investments of all time, Moody’s (MCO) 2000 divestiture from Dun & Bradstreet dipped 10% at first (despite Buffett’s buying) then exploded 3,000% over 20 years.

Remember Warner Bros (WBD), the Scarlet Letter of corporate M&A? Even it did well after its initial year of trading. After the 2022 carve out (along with Discovery Networks) from AT&T, it plunged 30% in its first year, before rebounding 50% in 2024.

Meet The New Vulcan

There’s a lot of alpha – investment outperformance – to be found in following SpinCo’s as they launch as separate public companies. Buying at the bottom of their orphan dip can lead to incredible performance.

That’s especially true when the parent company CEO leaves to join the SpinCo. Again, this is a kind of legal insider trading (the CEO knows where the best assets are) and you’ll frequently see them buying heavily after the spin-off is complete. That’s one of the best “tells” in the financial markets.

Another thing we’ve painfully and slowly learned about investing in public equity is this: very few companies survive for very long… and most fail. Studies show that more than 100% of the market’s total returns are generated by about 10% of all the stocks that ever trade. Over the long term (20-plus years), more than 50% of stocks lead to losses.

That’s why we stress Lindy Law investing. Lindy is the idea that the longer something inorganic has been successful, the more likely it is to continue. Think about a book that’s been in print for 50 years versus a brand-new title: which is more likely to be in print in 10 years? Think about marriages. Works the same way, doesn’t it?

It’s particularly applicable to businesses. It is very hard to guess which new businesses or institutions will succeed. A simple way to increase your batting average as an investor is to only invest in businesses that have a long track record (~40 years) of success. Few investors could have guessed that Vulcan Materials would be one of the greatest businesses of all time when it first began trading in 1957. But by 1980 that should have been obvious to all investors. The point is, you don’t have to guess: you can simply own the Lindy winners.

And So Now We Return To Rocks

The very best opportunity I can imagine in the financial markets would be to find a SpinCo from a firm like Vulcan Materials that has a 100-plus years of proven success, with an unassailable moat, world-class economics, and an industry-leading management team.

If you don’t have access to the full issue below, click here to subscriber to Porter Stansberry’s Complete Investor.

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.