Issue #38, Volume #1

Why I Lost Interest In Deep-Value Investing (and Two New Rules)

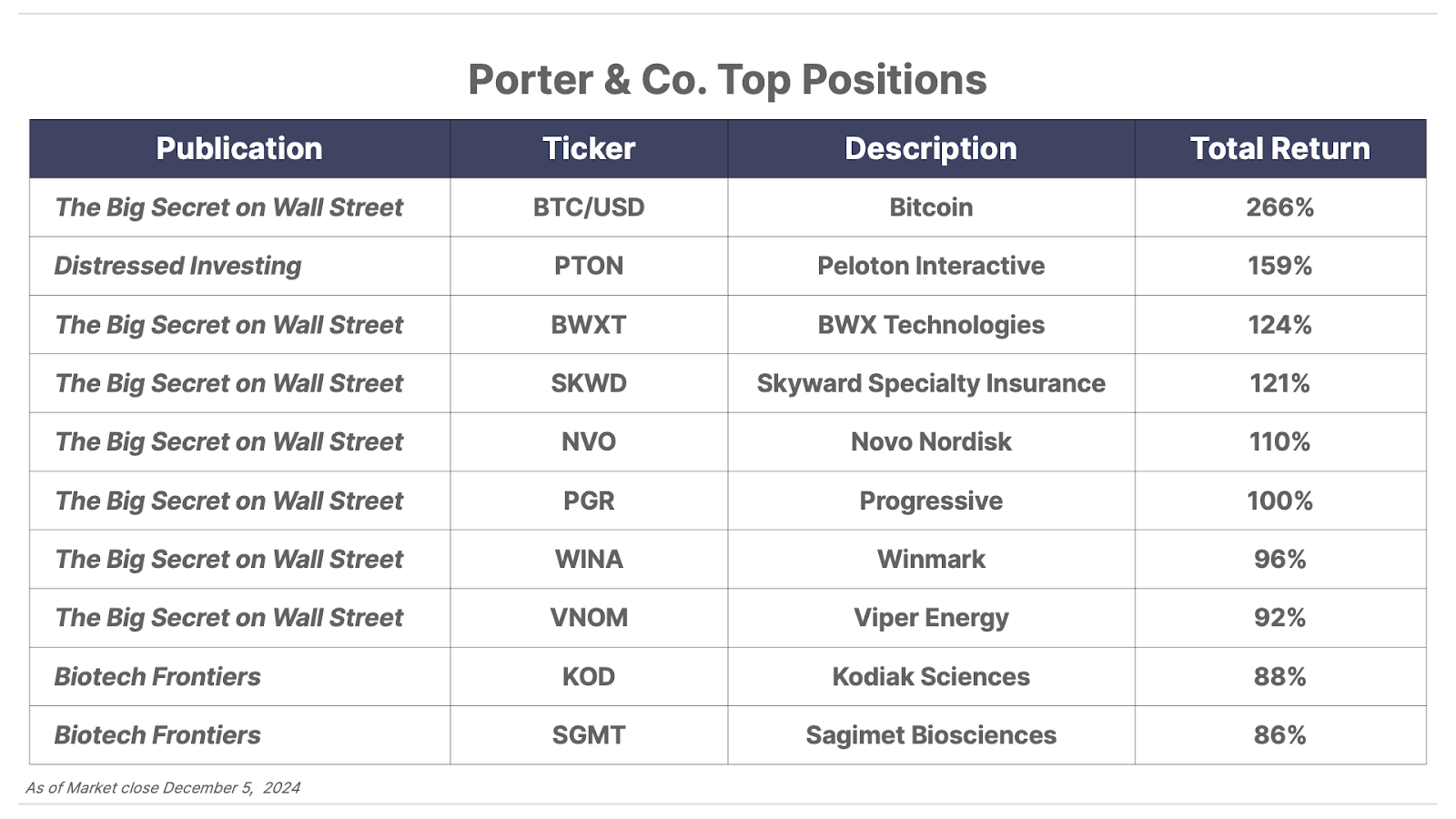

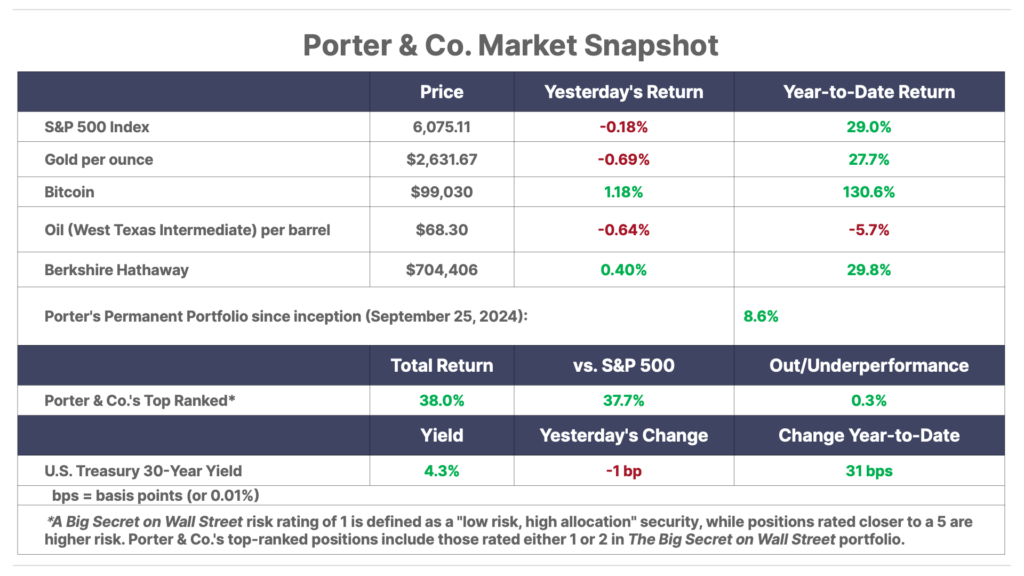

| This is Porter & Co.’s free daily e-letter. Paid-up members can access their subscriber materials, including our latest recommendations and our “3 Best Buys” for our different portfolios, by going here. Today we’re launching a new feature in the Daily Journal – the Market Snapshot, below. |

Three Things You Need To Know Now:

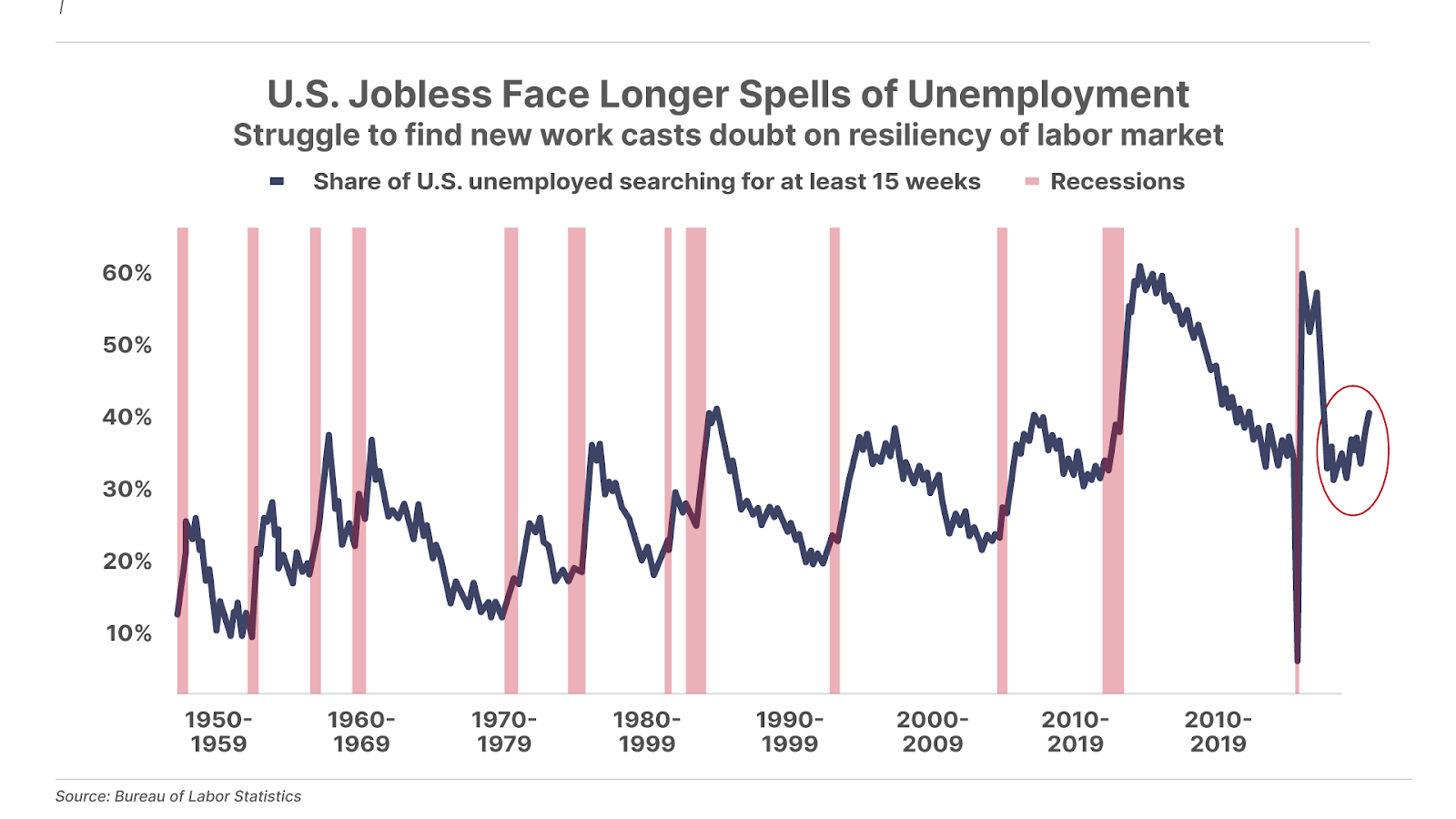

1. The U.S. labor market continues to weaken. The Bureau of Labor statistics released the November jobs report this morning, showing that the unemployment rate ticked higher, reaching 4.2% – a steady uptrend since April 2023, rising 1.7 percentage points over the period. There are now 1.7 million Americans in long-term unemployment, the highest in almost three years – and a 42% increase from a year ago. Despite a 227,000 rise in payrolls in November, there’s just not enough demand to hire the growing number of unemployed Americans.

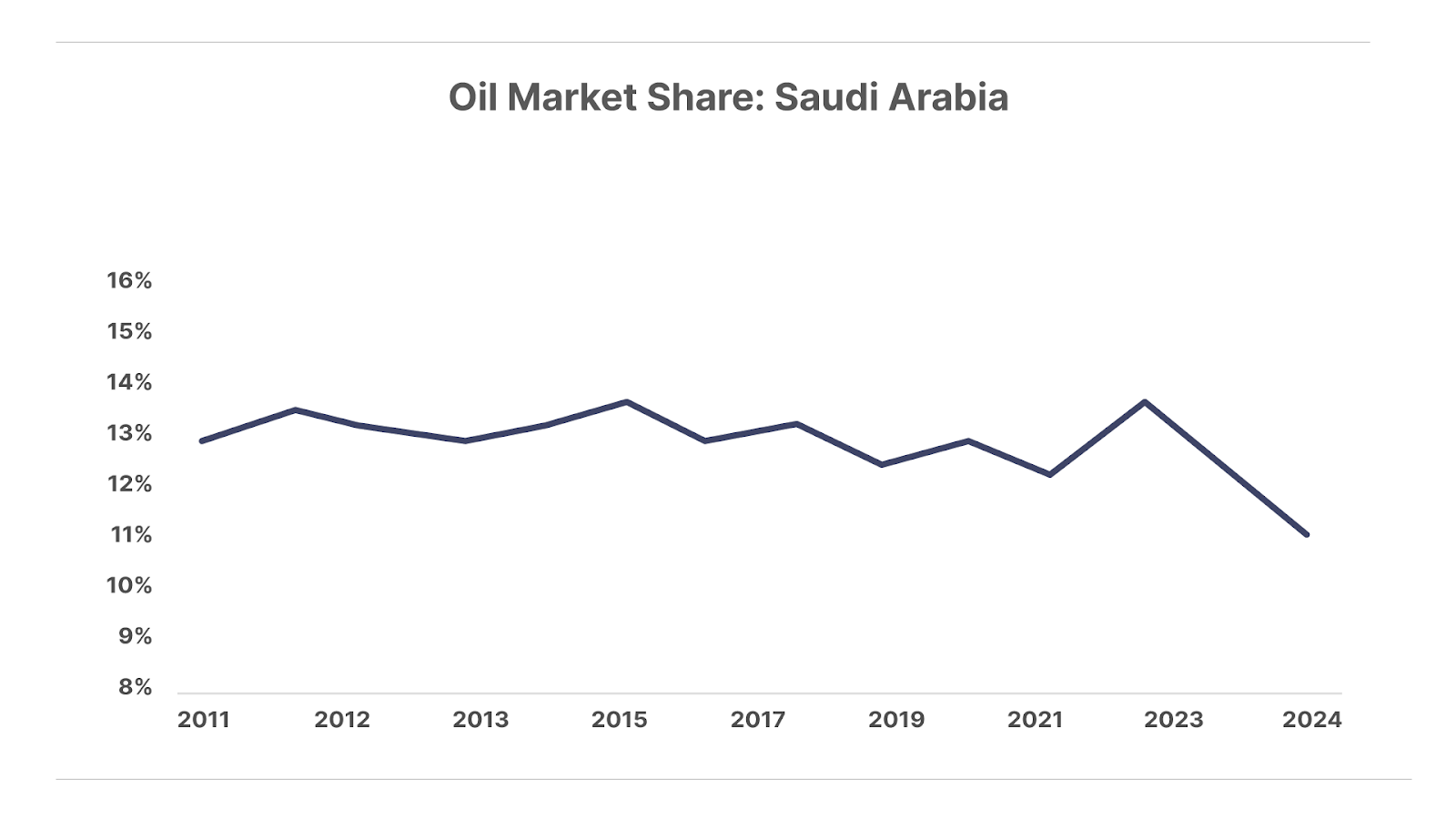

2. OPEC+ caught between a rock and a hard place. At yesterday’s OPEC+ meeting, the oil cartel delayed increasing production for the third time this year. Record output from U.S. shale drillers is the group’s biggest threat. The cartel’s de-facto leader, Saudi Arabia, has tried to boost prices by pushing for OPEC to cut production further, but that would come at the cost of surrendering market share. Another delay raises the spectre of a reversal in the cartel’s strategy – towards fighting for market share and launching a price war. The last time this happened, in March 2020 (also at the beginning of COVID), oil dropped to -$40 a barrel.

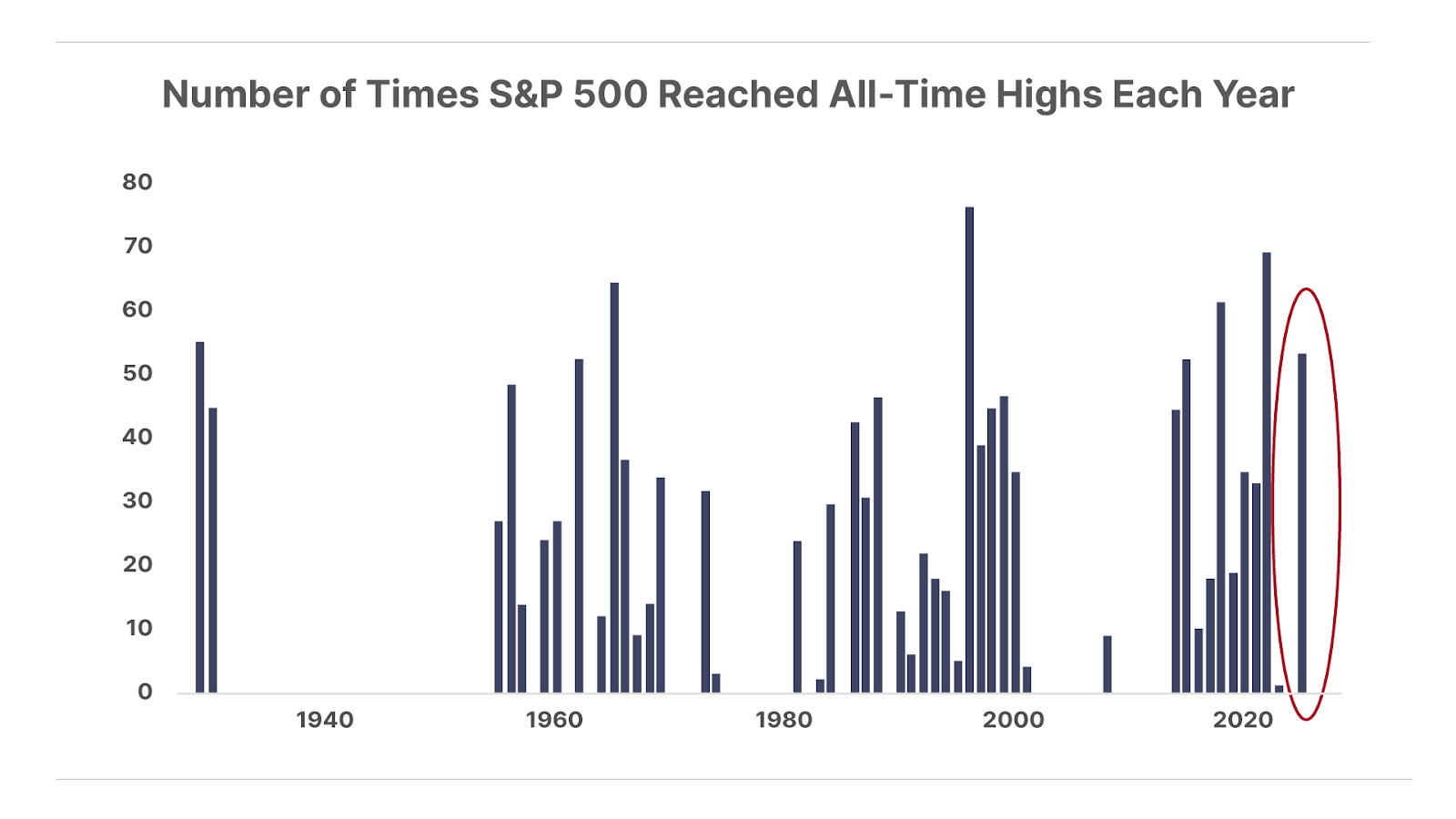

3. Signs of a Top… the highs keep coming. The S&P 500 has hit 54 all-time highs this year, the sixth-most in a single year (and the year isn’t over!) since 1920. Prior extremes like this happened just before major market tops in the late 1920s, late 1960s, late 1990s, and 2021. Is this time different?

And one more thing…

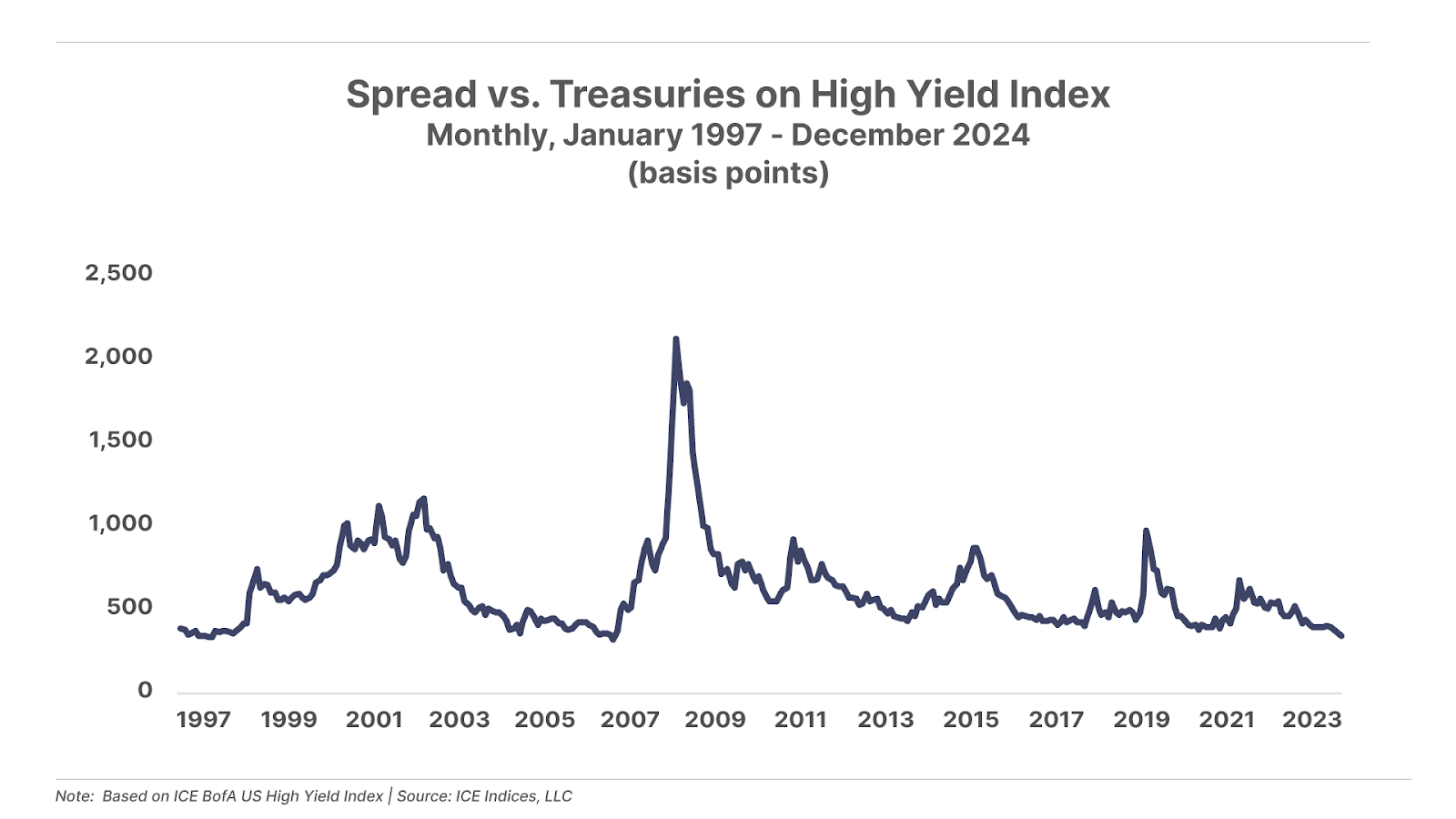

As Marty Fridson has written in Distressed Investing – and it’s worth pointing out here, too: The last time that high-yield spreads over Treasurys were as tight as they are now (that is, the last time that the difference between the yield of Treasuries, and the high-yield index, was so small) was in 2007. That was just before the Global Financial Crisis. And before that, in 1997… which was before the 1998 emerging-markets blowup… and in the runup to the dot-com crash.

Both times markets were swimming in liquidity. It was risk-on all the way. And today? Similar situation. Don’t say we didn’t warn you…

(How to position yourself for what’s next? It won’t be long before it’s shooting-fish-in-a-barrel time in the high-yield universe… when solid credits are sold off along with everything else. Marty Fridson is delivering extraordinary performance today. Since Marty joined Porter & Co. in March 2023, he’s made 21 distressed-bond and stock recommendations – of the 13 current open positions, 11 are in the green, resulting in an average portfolio return of 29.7%. And when the bottom falls out, the Distressed Investing portfolio will truly shine. Go here to learn more… You can also call Lance James, our Director of Customer Care, at 888-610-8895, or internationally at +1 443-815-4447.)

In case you missed it…

In this month’s Biotech Frontiers, released yesterday, analyst Erez Kalir focuses on a Big Picture inflection point that he says is crucially important for biotech holdings as well as every other investment in a portfolio… and he explains why Trump administration policies will likely lead to higher inflation…

In this week’s The Big Secret on Wall Street, we explore the massive divergence in valuations between stocks in the U.S. and those in the rest of the world. More money flowed into the U.S. stock market this year than any other time in history.

In Wednesday’s Daily Journal, Distressed Investing senior analyst Marty Fridson reflects on what he calls The Great Debacle, when in 1990, the collapse of Drexel Burnham Lambert precipitated a fiasco in the a high-yield bond market – not a single new issue came out for the entire year.

Becoming the Investor I Am Today

Why I Lost Interest In Deep-Value Investing (and Two New Rules)

We’re sharing parts of an investment classic that Porter wrote in 2018, at Stansberry Research. The essay below is about Porter’s evolution from being a value investor, into one who follows a few key fundamentals of investing that remains a centerpiece of what we focus on at Porter & Co. Since that transformation into this reliance of capital efficient businesses, Porter’s approach to building long-term wealth has remained startlingly consistent.

This is Porter today:

I’m updating the below (see my new two rules… keep reading). I’ve learned not to sell great businesses – because I’ve come to understand that the most likely way to earn a 1,000%+ return (a 10-bagger) was this: Buy a high-quality business, and give it time.

Sure, it’s not as sexy as buying a paradigm-shifting tech stock, but it’s way easier to do and it builds wealth just the same. If you’d bought NVR (NVR) or Moody’s (MCO) on my recommendation before the financial crisis in late 2007 (I wrote at the time that both would survive, and become great investments), you’d be up 1,068% and 1,894%, respectively… then you already know: never sell a great business.

Here’s Porter in 2018…

If there’s one concept I’d like every subscriber to know well, it’s capital efficiency…

I spent more than a decade trying to figure out why some companies ended up being such incredible long-term investments while other businesses didn’t, even when they created important technologies or popular new products.

I finally figured it out when I stumbled onto a long-lost essay that Warren Buffett wrote back in 1983. It basically gave away the whole secret… but he described it in such arcane accounting language that few people understood what he was saying.

I’d like to tell you about my personal search for the perfect investment.

I originally called my financial research company Pirate Investor…

No, that’s not because I was writing about some kind of semi-legal investment strategy based on stealing or marauding. It’s because when I started my own financial journal, I was fascinated by the radical changes new technologies were making in a wide range of major industries.

My core idea as an investor was to buy small, aggressive companies that were using new, disruptive technology to “pirate” market share from massive companies that were too big to handle the radical changes taking place.

We did very well with a lot of these ideas during the late 1990s… Many of these small, fast-growing companies soared – like Cree (white LEDs), JDS Uniphase (optical communication equipment), and Qualcomm (wireless chips). But then, in 2001 and 2002, I learned that investing in new technology isn’t always easy. Not every innovation works. And not every expensive stock grows into its valuation. Mistakes in this kind of investing are usually catastrophic. I made my fair share of big mistakes. Eventually, those mistakes soured me on only investing in new technology. I got tired of making “all or nothing” bets every time I made an investment.

By 2002, I was looking for safer, far less volatile investments… I wanted to find stocks that could serve as a stabilizing force for my portfolio. Along with Dan Ferris, I began researching deep value stocks. At Stansberry Research, we launched Extreme Value, which featured only value stocks – those that were trading at big discounts from their peers…

This approach was lucrative, and much safer than buying tech stocks. From 2002 to 2006 (the period when I was most involved in deep-value investing), we recommended 52 deep-value stocks in either my newsletter or in Extreme Value. Almost 90% of these recommendations went up, and the average return was over 50%, with an average holding period of a little more than a year.

How Deep Value Became Unsatisfying

Despite the success of our deep-value approach, I ultimately found deep-value investing unsatisfying…

Why? First and foremost, deep-value investing requires you to spend a lot of time studying marginal businesses. A stock that’s trading at four times earnings isn’t likely to be a great business. And as an outside, passive investor in common stocks, you’re not going to be able to fix these companies – not unless you want to invest hundreds of millions of dollars and become an activist. As a result, deep-value investing requires spending a lot of time with crappy businesses. And that was painful for me emotionally. I didn’t want to own a bunch of crappy businesses. I got totally fed up watching third-rate management teams bungle along.

But the deep-value approach bothered me for another reason…

Deep-value investing also suffered from what I call the ”Habitrail problem”… Habitrails are plastic enclosures that children use for pet hamsters. (When I was little, my brother and I had a hamster that lived for four years!) Habitrails contain tunnels and wheels that just spin and don’t lead anywhere.

When you’re a deep-value investor, all you’re doing is hoping that something happens that leads your shares to a higher valuation. That’s usually a buy-out. But sometimes the market just reprices the stock, sending shares higher. When that happens, you sell. And then, just like a hamster on a wheel, you’re right back where you started, looking for another crappy, cheap business to buy. You’re always in need of another deal. And sooner or later, of course, you’re going to make a mistake.

Finally… the most frustrating aspect of all… It was easy and lucrative to be a deep-value investor in 2002, 2003, and 2004. An epic bear market had lowered valuations across the board between 2000 and 2002. There were plenty of good opportunities.

But as stock prices rose as the bull market continued into 2005 and 2006, these opportunities evaporated. It became impossible to restock our portfolio. I found that deep-value investing was only a good strategy to follow during certain periods in the market. It didn’t work all the time for me.

Ultimately, I moved on from looking for deep value. I grew to loathe low-quality businesses and managers. I got tired of “running in place” – holding investments that never really got any better and that I had to sell and then replace to keep making money. And finally, I discovered that during big bull markets, the opportunity to buy deep value almost disappears.

What I was looking for was a great business… I wanted to find a business that would get better and better over time. I started studying companies that could grow their earnings consistently for decades. And I began studying Warren Buffett’s entire track record. How did he figure out which stocks would be safe and lucrative over the very long term?

What I discovered, I called “capital efficiency.” It’s a unique trait that allows some companies to grow their sales and earnings for long periods without large, corresponding increases to capital spending. Buffett wrote an essay in 1983 that spelled out the basics of how to find these businesses and why they are such great long-term investments. You can find it at the end of his 1983 letter. Buffett gave this essay a pretty snappy title: “Goodwill And Its Amortization: The Rules And The Realities.”

At the end of 2006, I’d written my first report about capital efficiency…

I summarize the main three points here.

First, you want a high-quality business. You quantify that by looking for a high return on net tangible assets (and total assets).

Second, you want to find a business that grows without big increases to capital spending or acquisitions.

And finally, you want to own a company you’re certain will still be in business for decades. Buffett explained where to find businesses like these: branded consumer products companies and property-and-casualty (P&C) insurance. Once you find them, then you just make sure you don’t pay too much for them.

I’ve been studying finance and economics since 1992…

I’ve been working professionally as an investment analyst since 1996. Virtually every day of the past 25 years or so, I’ve been looking for great investments or learning how to make them. I sure wish someone would have taught me this shortcut a long, long time ago.

To be a great investor, all you have to know is how to identify these kinds of investments. One or two of them (at least) are almost always available in the markets. The big advantage of these companies is that they get better with time…

As they grow, the returns for their investors improve. It’s almost a violation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: These companies get better and better with time because they scale with very little additional capital requirements. In general, the longer you hold these companies, the better.

Yes, you can use trailing stop losses to try and trade around the big problems that these stocks will run into every now and then. We recommended selling Disney (DIS) just before the financial crisis, for example, when we had a profit in the stock. It then fell more than 50%. Most people wouldn’t want to sit through that kind of volatility. But… if you can be patient… because they will constantly and relentlessly increase their dividends, these companies are the kinds of firms you should consider never selling.

If you’ve never bought any of our highest-quality, capital efficient ideas, it’s never too late to start…

Buffett didn’t invest in Coca-Cola (KO) until he was 58 years old. In 1987 and 1988, he invested more than $1 billion into Coke stock, which was 35% of Berkshire Hathaway’s entire equity portfolio. Ten years later, he’d made almost five times his money, about $7 billion in profit.

Most investors have a hard time believing that investment outcomes like this are possible for them…

But they are. If you could only follow one investment strategy and all of your liquid assets had to be invested in those ideas – no hedging – what would you own?

For me, there’s no question. I spent my life looking for the perfect investment. And I’ve found it with my super-high-quality, capital efficient approach.

Horse, meet water.

This is Porter today again…

Buying the shares of capital efficient companies is the foundation of my investment approach today – and the main focus of The Big Secret on Wall Street.

But as I mentioned above, of course I’m still learning… and I’ve recently added two rules to how I think about capital efficient companies:

1: Never sell a good business. If the business stops being good – if management goes astray… if there’s a fundamental change to the moat that protects the margins of the business… if there’s a structural, permanent change in demand for the company’s product – that’s one thing. But that’s very rarely the case. One bad quarter doesn’t mean anything. And a share-price correction is an opportunity to buy more – not a reason to sell.

2: Never pay too much. No matter how great a company might be… if you buy it at the wrong – too high – price, the chances that you lose money (or… earn a subpar return from a fantastic business) are dramatically higher. That’s why it’s so important to only buy when the share’s valuation is at the right point. (It’s what we focus on in The Big Secret – buying great companies… at the right price.)

Case in point: Texas Pacific Land (NYSE: TPL). It’s down sharply after a meteoric two-month rise since we recommended it in September, but it’s not down because of the fundamentals of the business. With TPL recently included in the S&P 500 Index, institutional investors were forced to buy it, and now they are unloading it. But I’m not selling, and I don’t suggest you do either.

What strategies have worked for you? How have you evolved as an investor? How have our products helped or hurt your efforts? What other sources of information and education have you used? Let me know at [email protected].

Good investing,

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, MD

P.S. Porter has a lot of passions, including investing… golf… fishing… and: razors.

In 2013, Porter set out to build the perfect razor. Two years and 1,000+ prototypes later, OneBlade was ready. All told, Porter has spent about $10 million in design, manufacturing, and development costs to make OneBlade what it is today: the best shaving experience in the world.

In honor of the holidays, Porter and the OneBlade team have put together something special for Porter & Co. readers: A full complex of OneBlade’s finest products at a steeper discount than anything offered ever before. It’s a package of the brand-new, industry-leading OneBlade LTHR Hot Lather Machine (if you’ve never shaved with hot lather… well, you haven’t lived), the Genesis Razor, OneBlade’s flagship stainless-steel masterpiece of form and function… 30 OneBlade HiCarbon SE replacement blades… After Shave Balm… and more.

Separately, these items cost $500… here, we’re offering the full box for only $295. You can see more here. (Hint: Christmas gift?…)

And – just to be clear, OneBlade knows that women appreciate a world-class razor too! – the package featuring the OneBlade women’s razor, Dawn, is here.

Mailbag

Ray P. writes,

Hi, Porter,

I know you recommended ZIM in September.

Their last quarter earnings blew away Street estimates as the company made over $9 per share. Their earnings and revenue forecast also blew away estimates. Initially the stock jumped over 15%, then it received four downgrades and its price has dropped over 30%. Do you have any idea why this is happening? Its forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio is less than one.

Thanks, Ray

Porter’s comment:

Hi Ray – Sorry to be argumentative, but I did not recommend Zim Integrated Shipping (ZIM).

Zim was covered in a guest essay in our September 10 Porter & Co. Spotlight, by analyst Tom Dyson.

On Tuesdays, I introduce readers to the most brilliant people I know in finance, people who I’ve known for decades and who are bona-fide genius investors.

As I explained:

My friend of more than 20 years, Tom Dyson, is not only the greatest investor you’ve never heard of, he’s also a savant at the single greatest investment challenge: your emotions.

There aren’t many real geniuses in the investment business.

That’s because investing isn’t all that hard, intellectually.

Where it’s difficult is the emotional side. Can you be patient enough? Can you be humble enough to cut your losses when it’s clear that you’re wrong? Can you remain disciplined to a winning strategy when there’s a drawdown?

Most people can’t do any of these things.

Tom, more than any other analyst, has always understood this challenge and has faced it head on.

Yes, I could tell you dozens of outrageous Tom investment stories, like when he piled into gold in the early 2000s or when he bought Bitcoin at $1 in 2013…

But, quite honestly, the reason you should read Tom Dyson each week isn’t merely because he is a genius at investing and will bring you outrageously good investment ideas.

You should read him each week because he understands the emotional challenges of putting capital at risk and, unlike anyone else in this business, he can guide you through those challenges.

Tom won’t just give you great investment ideas: he will sit in the fox hole with you and fight.

Read him and you’ll see immediately what I mean.

Then, as a gift to my subscribers, Tom gave away his insightful analysis on Zim. And those who followed it did incredibly well… the shares moved up 50% in just over two weeks. In the Daily Journal of September 27, I wrote: “Tom asked me to pass on to Porter & Co. members that he recommends selling shares of Zim at around $30 per share (up from around $17 when it was recommended… and $25 now).”

Of course, not every recommendation that Tom makes appreciates so much, so quickly. Zim’s move was equivalent to a 400,000% annualized gain!.

But that’s why I personally pay for Tom’s research.

He is a genius.

I sure wish you’d subscribe to him. He’s worth it.

You can access Tom’s research – at a special rate for Porter & Co. subscribers – here . It’s fantastic value for the money… I don’t know why anyone wouldn’t want to be able to tap into Tom’s brain.

As always, please share your thoughts with me directly: [email protected].