Issue #3, Volume #2

(No One Else Is Going To Tell You)

This is Porter & Co.’s free e-letter, the Daily Journal. Paid-up members can access their subscriber materials, including our latest recommendations and our “3 Best Buys” for our different portfolios, by going here.

Three Things You Need To Know Now:

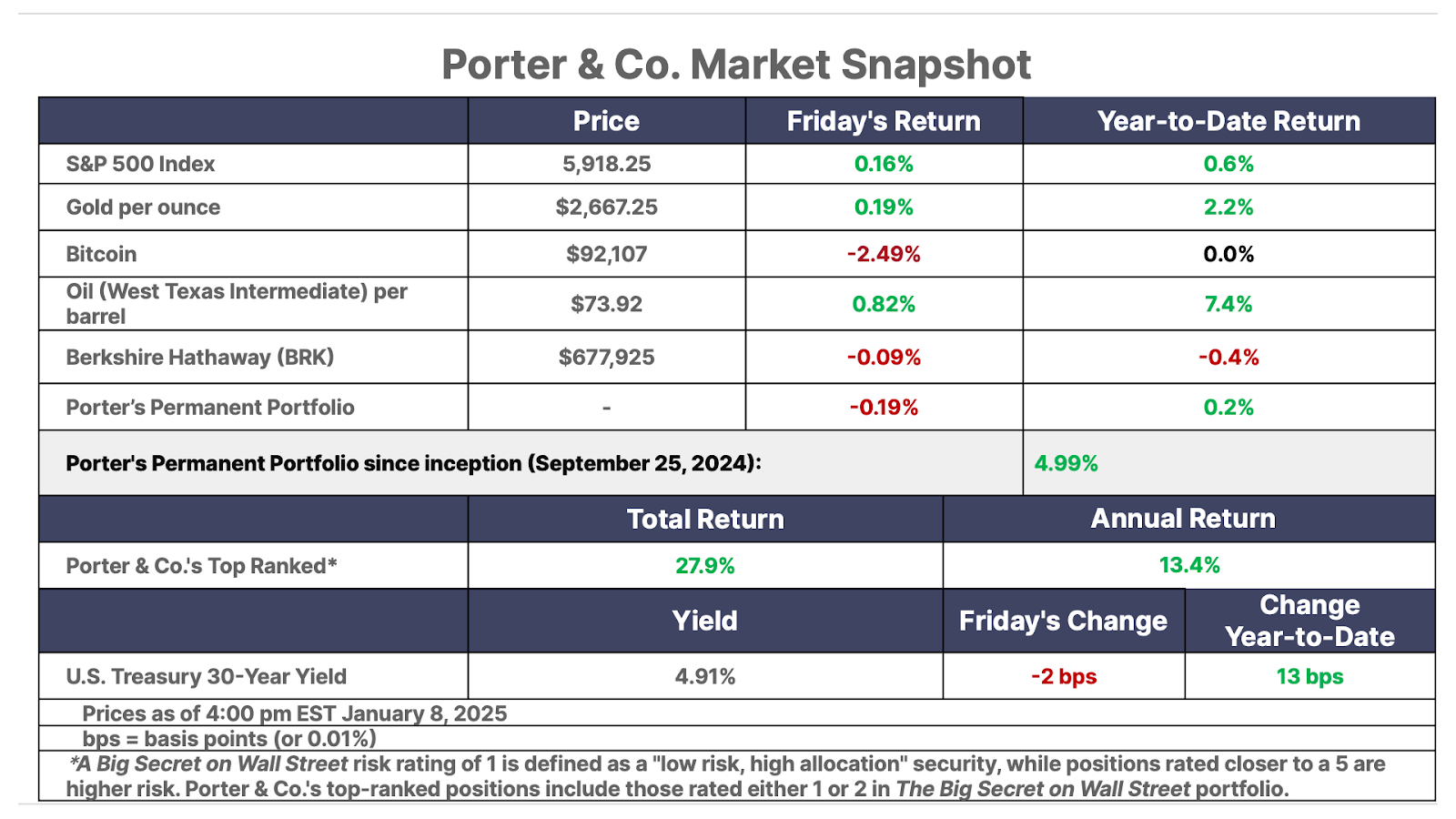

1. Fed rate-cut odds plunge following strong jobs report. This morning, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported U.S. payrolls grew 65% more in December than the 155,000 increase Wall Street economists had forecasted. Following the mixed bag of employment data earlier this week, today’s strong report caused the odds of a March rate cut to fall to just 25% from 41% yesterday, according to the CME’s FedWatch tool.

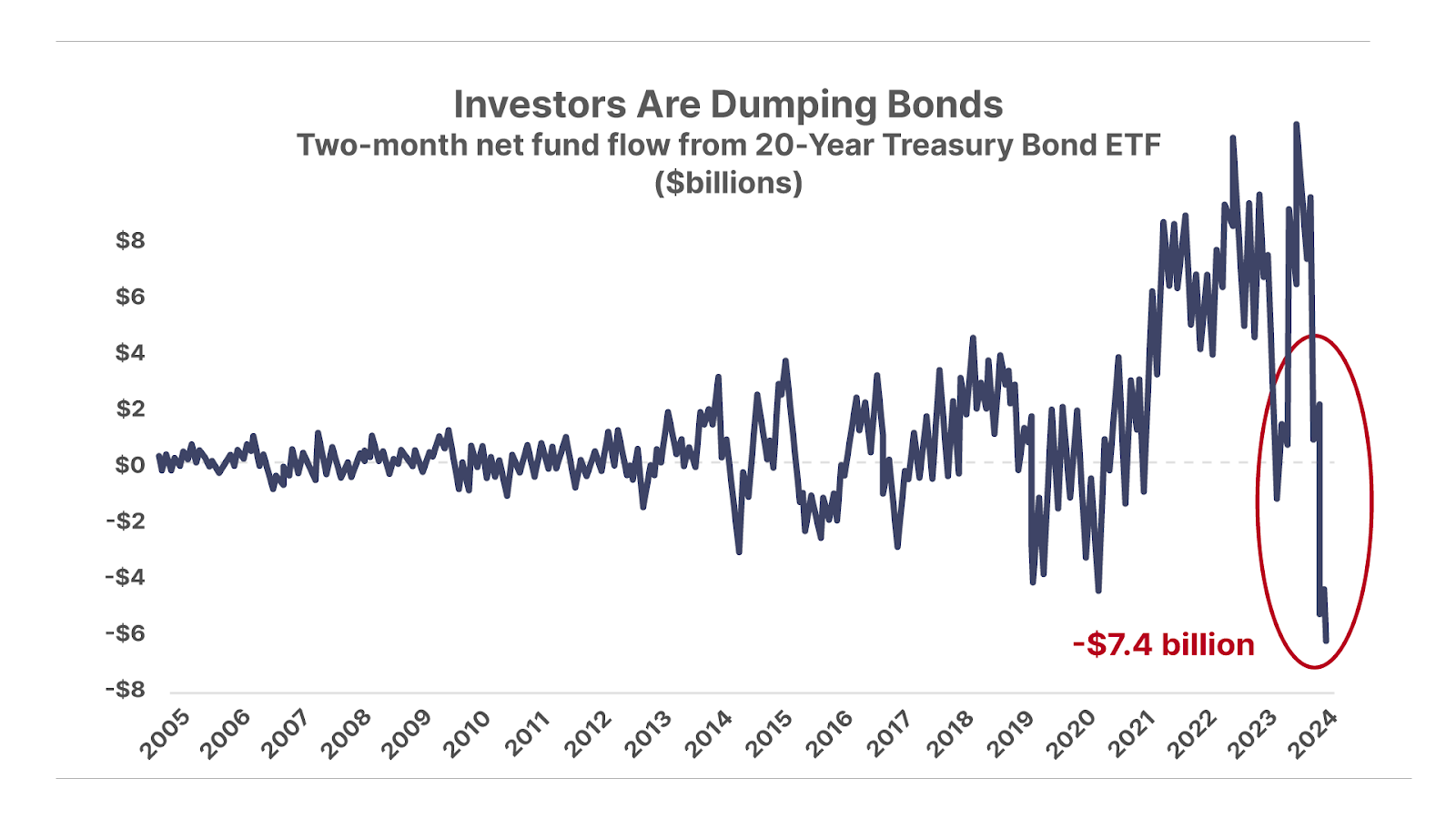

2. Investors are fleeing bonds. The iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) – the most popular bond-tracking ETF – has seen a record $7.4 billion in net outflows over the last two months, trouncing the previous record of roughly $5 billion seen in mid 2020. And with long-term rates surging to new 52-weeks highs following this morning’s hot jobs report, this trend appears unlikely to reverse anytime soon. When bonds speak, equity investors should listen.

3. Another nail in the ESG coffin. During the heyday of the environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”) investing movement in 2022, we called a main perpetrator of the nonsensical policy one of the “two men destroying America.” Yesterday, the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock – headed up by Larry Fink, one of those two men (go here to find out about the other) – announced that it’s withdrawing from the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, a United Nations-backed effort anchored in the notion (in Fink’s words) that “climate risk is investment risk.” The Wall Street Journal called it “a remarkable U-turn for a company that was once a poster child” of ESG. Turns out, ESG is the investment risk.

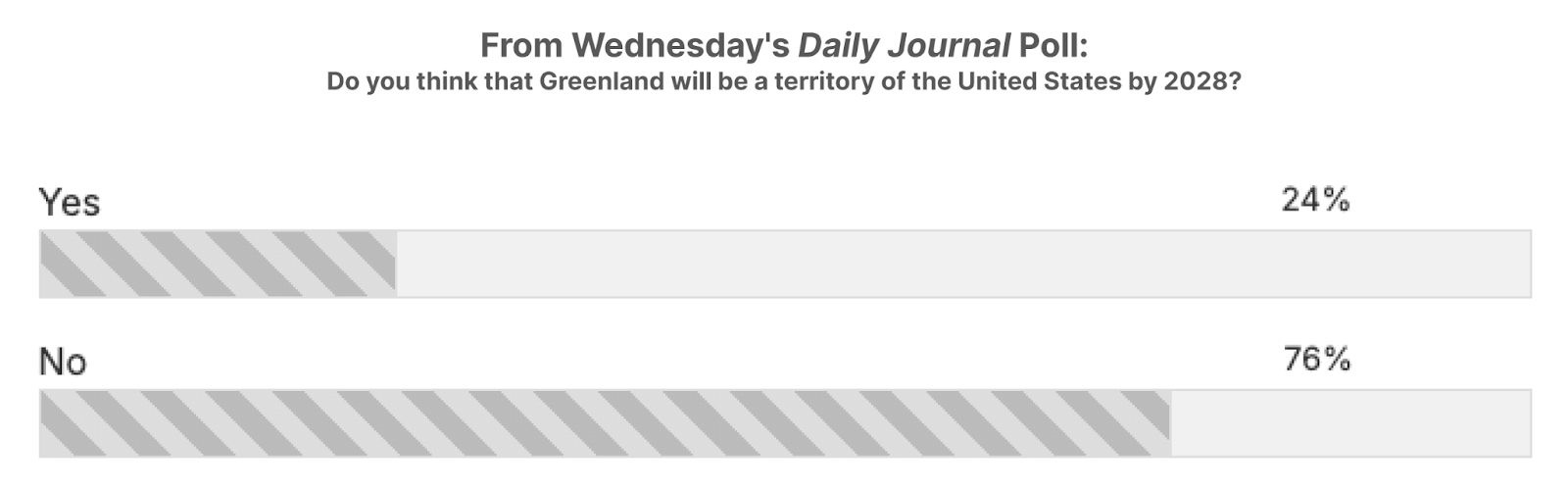

Poll Results… Greenland, the 51st state?

On Tuesday, President-elect Donald Trump made clear that he’s interested in the U.S. taking control of Greenland. On Wednesday we asked Daily Journal readers if they thought the Danish territory would be a U.S. territory by 2028. Turns out most think it’s bluster and bluff, with more than three-quarters of readers who took the poll saying No, Greenland would not be a territory by 2028.

Heeding Buffett’s Warning

(No One Else Is Going To Tell You)

On May 29, 1969, Warren Buffett announced he was retiring.

It was an announcement that his partners were not happy to receive. Between 1957 and the end of 1969, the Buffett Partnership Ltd. produced total returns of 2,794%. Buffett had been compounding their capital at a rate of almost 30% a year. Even after expenses and profit sharing, the limited partners’ capital had grown 23.8% a year.

Buffett was closing the partnership because, with $100 million under management and with the huge rise in stock prices during the 1960s, he could no longer guarantee outstanding results. “I really felt that the expectations of people had been so raised by our experiences over the past 13 years that it made me very uncomfortable.”

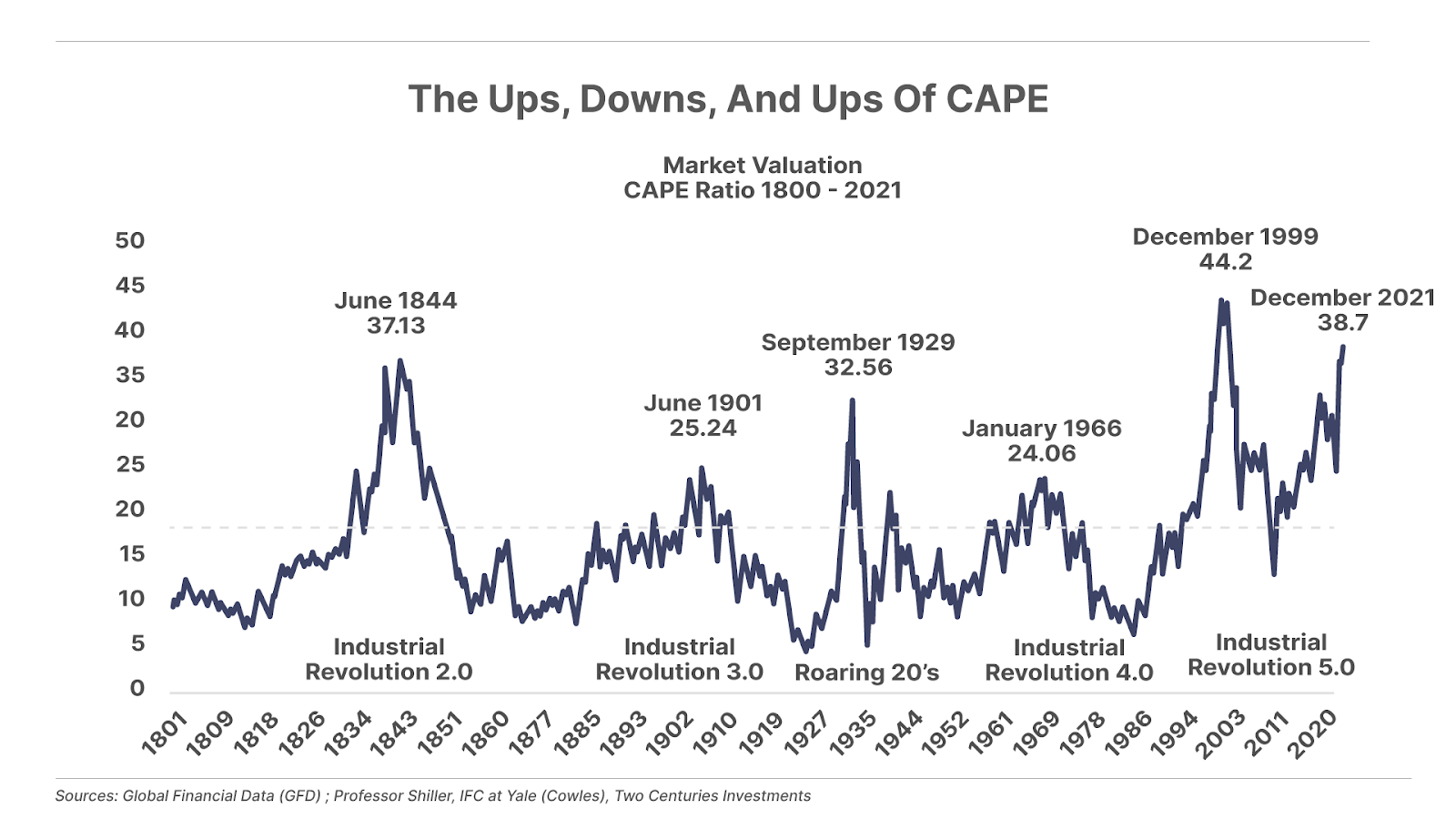

We can see how expensive stocks became during the Buffett Partnership by looking at the Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio of the S&P 500 (“CAPE”). This ratio compares the market value of every stock in the S&P 500 to the net income of those businesses, on average, and adjusted for inflation, over the previous 10 years.

In short, this number tells how many years’ worth of profit stocks are trading at, on average.

In the early 1950s, when Buffett first began investing professionally at Graham-Newman in New York, the CAPE ratio of the S&P 500 was around 10. Stocks have only rarely traded at a lower multiple in the U.S.

But, by the mid-1960s, the CAPE was over 20! It peaked at 24 in early 1966.

At the time (in the 1960s), stocks had only been more expensive (on average) during the enormous boom in the late 1920s, after which stocks had crashed. Buffett understood that stocks were trading at levels that were bound to disappoint most investors. He didn’t want the pressure of trying to continue to compound a large amount of capital ($100 million) by 30% a year in that kind of environment. He knew doing so would be virtually impossible.

And so, in 1969, when Warren Buffett hosted a group of his closest friends at the Colony Hotel in Palm Beach, he wondered what they were going to do with their investments for the next decade. Where would they “hide” until conditions were more favorable in the stock market?

Buffett asked his friends: If you were stuck on a desert island for the next 10 years and you had to hold 100% of your wealth in one stock, which would you choose?

Buffett picked Dow Jones (the publisher of the Wall Street Journal). It was an interesting choice, given that he didn’t own shares and, of course, rather than buying Dow Jones he later bought a large stake in The Washington Post. (Note: many sources report incorrectly that his desert island stock was The Washington Post. But that’s false. According to his biographer, Alice Schroeder, Buffett’s desert island stock in 1969 was Dow Jones.)

Bill Ruane, the famous founder of the Sequoia Fund, was the smartest of the bunch. He chose Berkshire Hathaway – because that’s where Buffett was putting all of his own capital.

Charlie Munger likewise bet on Buffett by choosing Blue Chip stamps, which Buffett was also heavily invested in and which in turn owned several of their investments, like Berkshire, Rockville Bank, and, later, See’s Candies.

Rick Guerin would end up in second place. He picked American Express. It did very well – but not as well as Berkshire.

Stan Perlmeter chose Polaroid, which, at the time, was a high-flying tech stock thanks to its incredible chemistry that was bringing photography to the masses. But, despite having a monopoly on one of the most popular new consumer technologies, its stock would crash (by more than 80%) in the ’73-’74 bear market, after its earnings fell 73% in the second quarter of ’73.

Buffett would spend the next decade or so struggling to improve Berkshire’s textile business, while investing all its cash flows into other businesses – most notably The Washington Post and insurance company Geico.

Meanwhile, stocks, on average, continued to get less and less expensive. And interest rates (along with inflation) continued to creep higher and higher.

Finally, in June of 1982, 13 years after Buffett’s meeting at the Colony Hotel, the CAPE of the S&P 500 would bottom at 6.5. Right on cue, BusinessWeek pronounced the “death of equities” and explained why Americans would never return to stocks. Buffett would soon shutter Berkshire’s mills forever and create the greatest long-term investment record of all time.

Today the CAPE ratio of the S&P 500 is 37. And Barron’s says you should “embrace the bubble.”

What does Buffett say?

Buffett constantly denies trying to time the markets. But, if you watch his moves carefully, you can see that he undoubtedly does time the market.

He hid in Berkshire at the peak of the 1960s. He bought heavily – after – the ‘87 crash. He bought General Re at the peak of the 1990s, because it owned a huge pile of bonds that shifted his exposure away from stocks.

And today, with stocks trading at their highest valuations since the 1990s bubble, Buffett has raised $300 billion in cash, the most amount of cash he’s ever held inside Berkshire Hathaway.

It’s Buffett’s final warning. And I hope you’ll heed it.

My advice? Unless you know for certain that you can hold your investments, without fail, for the next decade at least, it’s time to sell. I have no doubt that, like Polaroid, many of today’s top tech stocks will develop incredible products and grow revenue and profits substantially into the future. But… the cheapest of these high-quality businesses is trading at 25 years’ worth of profits. Most of this success has already been “priced in.”

In broad terms, energy still seems reasonably priced. And there are many high-quality, stable businesses (like Hershey (HSY), for example) that are still reasonable investments.

I’m not saying stocks are going to crash tomorrow. But I think it’s very foolish to believe that stocks, on average, are likely to do well over the next decade.

And nobody else in the media is going to warn you.

Let me know what you think by sending comments to [email protected]

Good investing,

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, MD

P.S. As humans, we like predictability. Having a good sense of what comes next reassures us that we’ll be here to see the sun come up tomorrow.

And as investors, we absolutely crave predictability. To be able to see through the mist of markets to know what comes next would be a ticket to market victory – and riches.

Our friends at TradeStops – which is the service we here at Porter & Co. entrust with calculating our portfolio return data – are world-class data crunchers. And they’ve found a pattern of predictability in markets that’s unlike anything you’ve seen before.

Actually, you have seen it before – in the seasons of the Earth. TradeStops has discovered a dimension of seasonality in stocks that is so predictive and powerful that it even works for buying options.

We don’t talk about options very often. Unless you’re selling them – the only options strategy we advocate – buying options is like burning cash. However: TradeStops may have found the key.

TradeStops CEO Keith Kaplan has put together a presentation that explains it all.