Electric Vehicles Are Actually Thriving…

Just Not in America

Electric vehicles (“EV”) were supposed to be the “next big thing.”

For years now, we’ve been told that traditional, gas-powered, internal combustion engine (“ICE”) vehicles would soon be obsolete – replaced by a new generation of high-tech, “zero emission” EVs.

Many automakers – including U.S. giants Ford Motor (F) and General Motors (GM), which have long dominated the domestic ICE market – embraced this idea, investing billions in new EV factories, workers, and models, and projecting wildly optimistic growth in EV sales. For example, Ford is estimated to have invested roughly $20 billion in EVs to date (down from original plans of more than $30 billion)… That’s a lot for a company that earned a little more than $40 billion in net income over the past decade.

Beginning in 2008, the U.S. government has been providing tax credits of up to $7,500 per vehicle to encourage this shift.

And Wall Street fully bought in, pushing up valuations for many EV makers to levels implying the EV revolution was just around the corner. (How else can you justify EV-darling Tesla (TSLA) trading at 250 times earnings?)

There’s just one problem…

That revolution has yet to arrive.

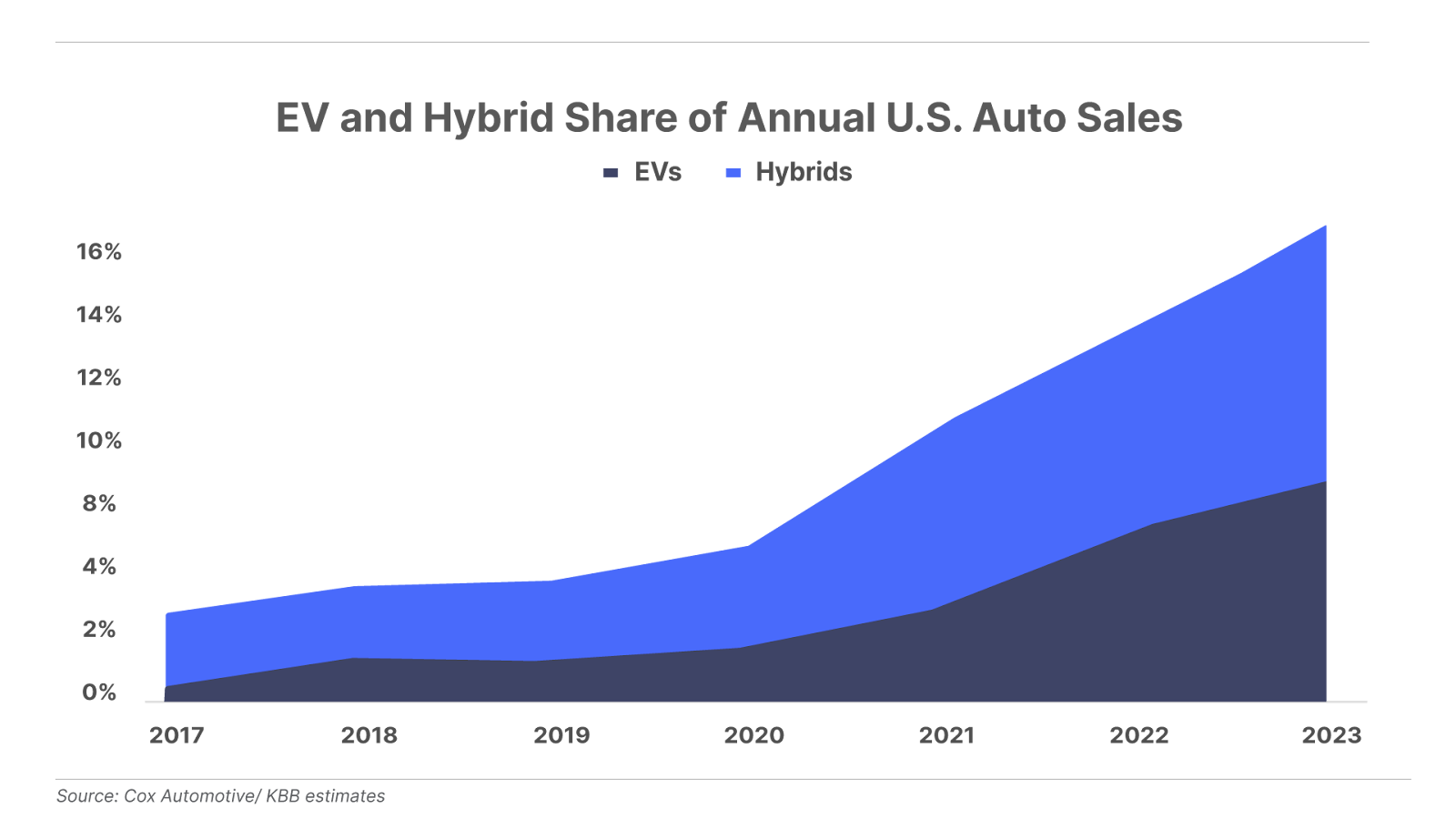

Following a sharp increase in 2021 and 2022, U.S. EV sales growth has slowed dramatically, with EVs accounting for just 8% of total U.S. auto sales in the latest quarter, according to Cox Automotive. That’s not nothing… but it’s far short of expectations: Just two years ago industry experts and EV advocates were predicting they would have more than 20% of the market by now.

Meanwhile, Cox also reports unsold EVs are piling up on dealer lots, with inventory reaching 136 days of sales according to the latest available data. That’s nearly double the 78 days of ICE vehicle supply, which itself is higher than the long-term historical average of around 60.

Worse, most automakers aren’t making a profit on the EVs they do sell. Ford – the only major company that breaks out results for traditional and electric vehicles separately – lost $4.7 billion on EVs last year, or roughly $40,000 per vehicle.

As a result, many of the automakers that went “all in” on EVs just a few years ago are now pulling back – delaying new EV models and refocusing efforts on a more diversified mix of offerings, including popular gasoline-electric hybrids, plug-in hybrids, and new ICE models.

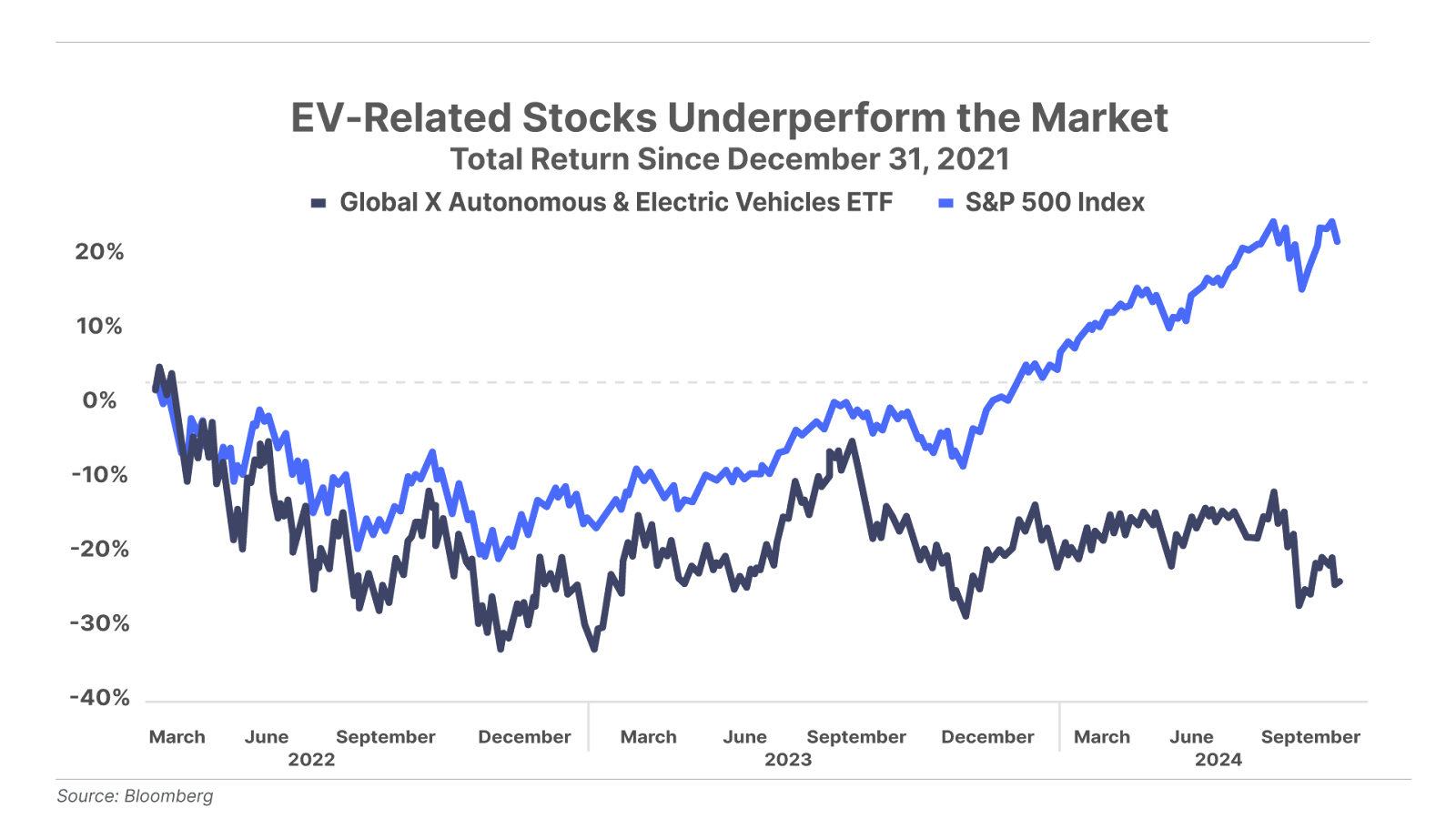

And, not surprisingly, the EV-stock boom has sputtered, with shares of many automakers that are increasingly focused on EVs down significantly from their 2021-2022 peaks, including GM (-29%), Tesla (-43%), and Ford (-58%). EV startups like Rivian Automotive (-92%) and Lucid (-94%) have fared even worse.

In short, contrary to rosy forecasts, it appears most U.S. consumers simply aren’t interested in EVs today.

Why the U.S. EV Revolution Is Stuck in Neutral

There are plenty of reasons U.S. consumers have been hesitant to embrace EVs to date, including fear of change and a nostalgic fondness for gasoline-powered cars.

However, the two most important reasons are as simple as they are obvious: price and range.

Price. We’ve written previously about Tesla’s pricing problem. The company’s focus on high-end, high-performance EVs means its vehicles are significantly more expensive than most ICE vehicles, putting them out of reach for most consumers.

However, this problem isn’t exclusive to Tesla. Instead of making more affordable mass-market vehicles, traditional automakers like Ford and GM emulated Tesla by focusing heavily on higher-end EVs – including vehicles like the GMC Hummer EV and the Ford F-150 Lightning, each of which can carry a price tag of $100,000 or more.

Even with continued U.S. government tax subsidies – which, following Congress’s 2022 so-called Inflation Reduction Act, are now in place until at least 2032 – these vehicles remain too expensive for most consumers.

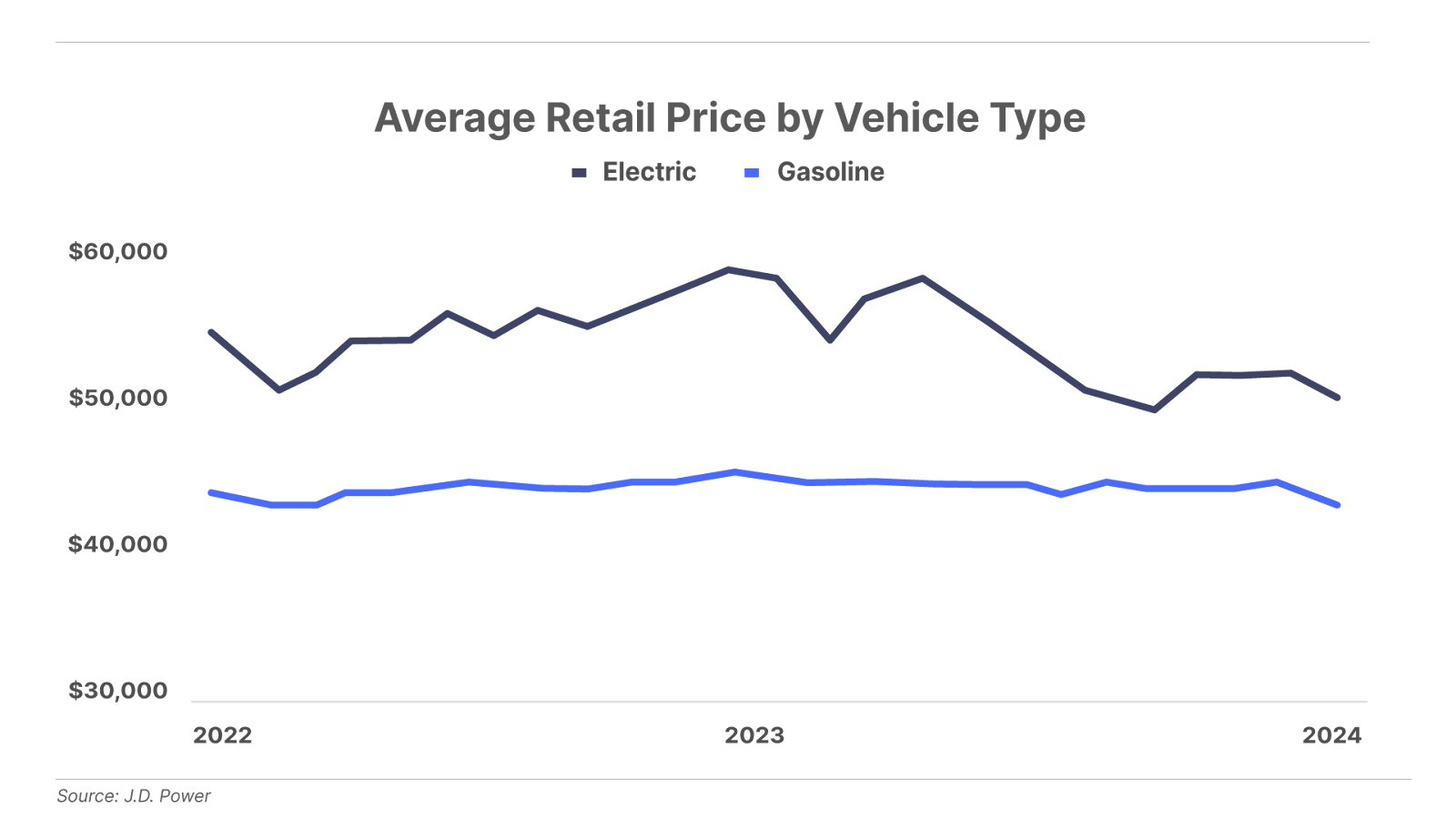

So, despite a significant increase in EV offerings in the U.S. over the last several years, as the chart below shows, the average EV is still significantly more expensive than the average ICE vehicle, which currently sells for around $45,000.

Many consumers apparently see no value in paying a premium price for an EV relative to a traditional ICE vehicle, and this is likely to become an even more important point when the economy weakens. Also, as we’ve noted recently, a growing body of evidence indicates the long-awaited recession may finally be here.

While the gap between EV and ICE prices has narrowed in recent years, the price of EVs will almost certainly need to move more in line with ICEs before any significant increase in adoption begins.

Range. The median EV can drive 200 miles before requiring a charge, while the median ICE vehicle can go 400 miles before needing a fill-up. And gas stations are ubiquitous, whereas charging stations are in short supply. This limited battery range and relative lack of charging infrastructure in the U.S. also make EVs less attractive to many consumers – particularly those who regularly drive longer distances.

The total number of EV charging stations in the U.S. has nearly tripled over the past five years, from around 23,000 to 68,000. But that’s still just a fraction of the nearly 200,000 retail gasoline stations in the U.S. These fewer EV charging stations are also far less equally distributed than gas stations, with many rural areas not served by an interstate highway lacking any places for EV drivers to plug in at all.

Finally, even in areas where charging stations are available, they can often be hard to find, broken, or have relatively long wait times – far longer than for, say, a gas pump – once found.

According to consultancy McKinsey & Co., the U.S. will ultimately need 1 million charging stations to facilitate widespread EV adoption. Considering the Biden administration approved $7.5 billion in 2021 for a program to install 500,000 charging stations – which has delivered just seven stations to date – it seems unlikely that the U.S. will reach that target anytime soon.

None of this should be surprising to most readers. But what you may not realize is that an EV revolution is taking place… it’s just happening on the other side of the world.

The EV Revolution Is Already Happening in China

While U.S. EV sales have yet to reach even 10% of total vehicle sales, they are booming in China, where they already account for roughly 40% of all vehicle sales.

And this is happening because Chinese EV makers – most notably industry-leader BYD (OTC: BYDDY), which last year overtook Tesla as the world’s best-selling EV company – are doing what U.S. and European EV makers have failed to do thus far: they’re solving the two biggest barriers to EV adoption, price and range.

First, and most importantly, they’ve figured out how to mass produce quality EVs at an affordable price. There may be no better example than BYD’s new Seagull, introduced in China earlier this year.

This model starts at less than $10,000, or roughly one-fifth the cost of the average EV in the U.S. Yet it boasts an above-average range of 252 miles, relatively quick charging (30% to 80% in 30 minutes), and a modern interior created by Lamborghini designer Wolfgang Egger (earning the Seagull the nickname “Lamborghini mini”).

According to automotive consultancy Caresoft Global, the Seagull is “efficiently designed, built, and executed” with “better than expected quality and reliability.”

Even more impressive, BYD has been able to sell this high-quality, low-priced EV at a profit, a feat that most Western automakers have been unable to do even with high-priced EVs (because of the higher production cost of EVs relative to ICEs, and the inability to scale due to tepid demand).

Terry Woychowski, a former GM executive and current Caresoft president, says the Seagull should be a “clarion call for the rest of the industry.”

China also appears to be well on its way to solving the problem of range anxiety – a driver’s fear of running down the battery because of a lack of charging options. For example, BYD, in particular, offers EVs with ranges approaching 400 miles per charge – equal to that of the median ICE in the U.S. – and recently unveiled a new plug-in hybrid vehicle with a remarkable range of 1,300 miles.

These advancements in range are largely due to improvements in battery density and efficiency – the world’s top EV battery-maker, CATL, is based in China – and the relatively lighter, smaller profile of new Chinese EVs.

What the U.S. Can Learn From China

While Chinese vehicles aren’t currently available in the U.S., the country’s booming EV market still has some significant implications for the U.S. and global auto industries.

First, it shows that the EV revolution is proceeding, whether or not American consumers are on board. And even if U.S. adoption continues to lag, it appears inevitable that China will begin exporting huge numbers of these EVs to other countries – especially emerging markets, where their low-cost advantage would be welcomed – taking global market share from U.S. and European automakers.

Second, it confirms what U.S. automakers like Ford, GM, and even Tesla need to do to be successful in the EV market: They must pivot from high-end, high-cost EVs to more affordable – yet still high-quality – mass-market options.

Of course, whether those companies will (or even can) follow China’s lead and begin offering profitable, lower-cost EVs is another question entirely.

Tesla’s first attempt at a mass-market sedan – the $40,000-plus Model 3 – is still more expensive than the average ICE vehicle, and its long-awaited (supposedly) sub-$30,000 Model 2 won’t begin production until 2025 at the earliest.

The only EV currently available in the U.S. for less than $30,000 is the Nissan Leaf, starting at $29,280. Yet this tiny four-door hatchback gets only 149 miles per charge, and its no-frills interior is unlikely to be confused with a “Lamborghini mini.”

Meanwhile, Tesla CEO Elon Musk has admitted that his company would be “demolished” by Chinese EV imports without tariffs or trade barriers that keep prices artificially high. Tesla simply can’t profitably sell its cars at the same low price points as Chinese competitors. Other U.S. automakers would almost certainly face a similar fate with their EV offerings.

In the end, whether or not the revolution takes off in the U.S. may come down to a political decision. The U.S. government has set lofty EV adoption goals, but would it be willing to allow free market competition to bring down prices – and potentially put high-cost U.S. producers like Ford or GM (and their high-profile union jobs) out of business – in order to achieve them?

The popular misperception of a stalled EV revolution has crushed the share prices in one industry that relies on EV sales for its growth. But next week in The Big Secret on Wall Street, we’ll make the case for why this is the ultimate contrarian investment in today’s otherwise richly priced market – with a special security that offers low risk and significant upside. Click here to be among the first to receive this brand-new paid research.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD