Issue #5, Volume #3

Yes – And Here Is How You Know For Sure

This is Porter’s Daily Journal, a free e-letter from Porter & Co. that provides unfiltered insights on markets, the economy, and life to help readers become better investors. It includes weekday editions and two weekend editions… and is free to all subscribers.

Past issues can be found here.

| An AI bubble… CAPEs are high… Buffett Indicator is high… Nvidia’s amazing, but can it keep going?… Druckenmiller and Robertson go head-to-head… Keep your head – get the right price… More bad jobs news… Gold wins the poll… |

Today, Porter turns the Journal over to Erez Kalir, editor of Porter & Co.’s Tech Frontiers.

Erez has degrees from Stanford, Yale, and Oxford, has studied biology, finance, and law, and has worked at McKinsey & Co. and for Julian Robertson at Tiger Management. Porter & Co. has recently expanded the domain of Erez’s investment research to include tech stocks, the blockchain, and science beyond his original focus of biotech.

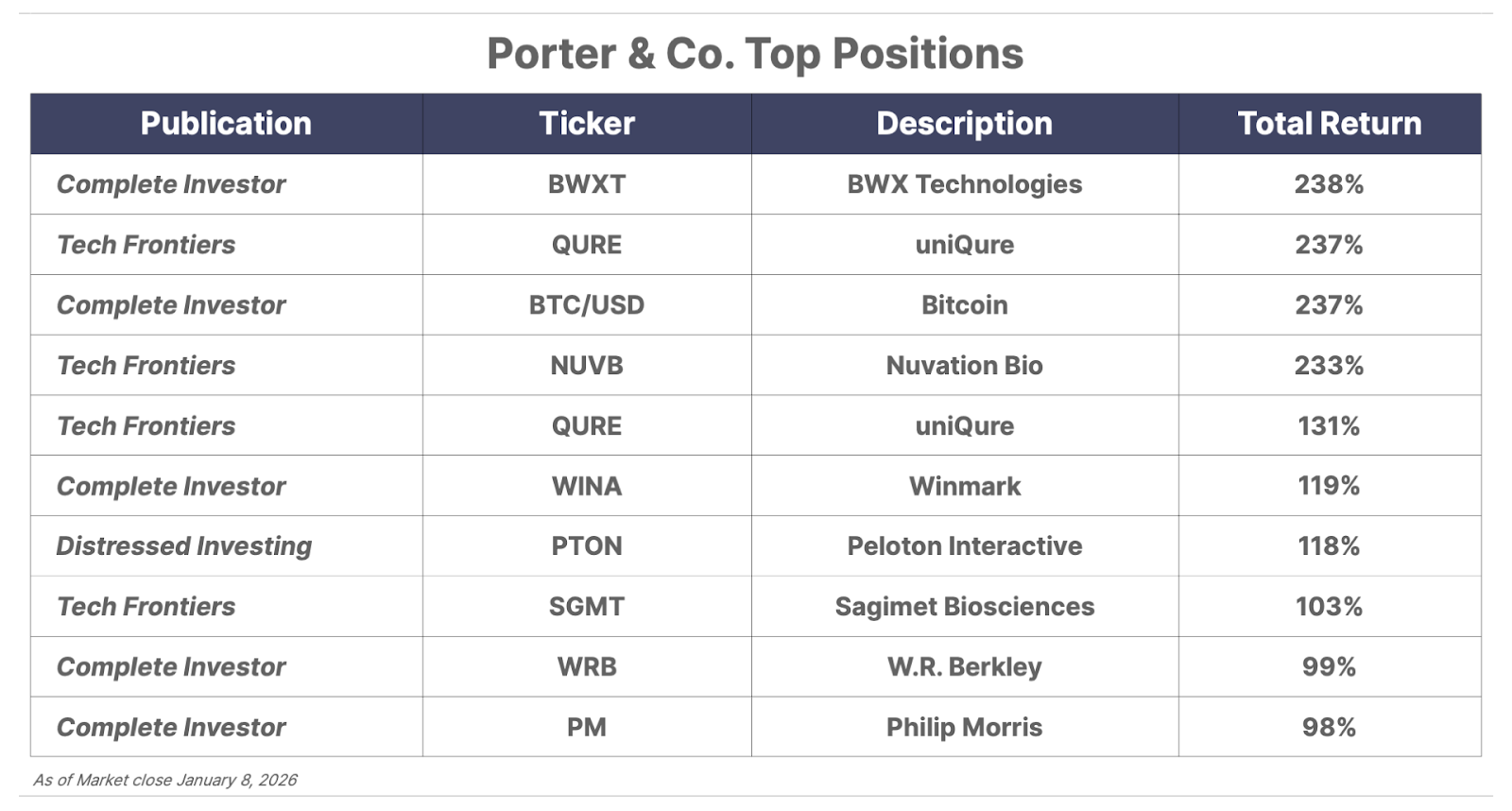

Six of the 12 open positions in the Tech Frontiers portfolio are up 50% or more since he recommended them. There are three more that doubled before he suggested selling them to take gains. Overall, the open portfolio is up 49% since he launched it in 2024.

In today’s Journal, Erez discusses the extraordinary valuations seen in stocks of companies in the artificial-intelligence (“AI”) sector and explores whether or not there is an AI bubble…

What does it really mean to be in an AI bubble?

In his classic book Manias, Panics, And Crashes: A History Of Financial Crises, Charles P. Kindleberger defines a financial bubble as “an upward movement in prices… that feeds upon itself; rising prices attract ever-increasing numbers of buyers seeking to profit from the price rise, until the process becomes unsustainable.” At the heart of Kindleberger’s definition are two crucial elements that define any bubble – and that can be applied to an artificial-intelligence (“AI”) bubble:

-

Asset prices that detach from fundamentals, driven by

-

Excessive optimism and herd behavior

Let’s begin with the relationship between asset prices and fundamentals. Historically, three measures have proven to be the most powerfully predictive indicators relating current stock valuations to future returns:

-

The 10-year cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (“CAPE”) ratio

-

The stock market’s overall price-to-book ratio, sometimes called “Tobin’s Q”

-

The ratio of the total market capitalization of stocks to U.S. GDP, sometimes called “the Buffett indicator”

Today, all three indicators are at historically high levels – in fact, they’re flashing red. The CAPE ratio for U.S. stocks stands at 39.5x, after a minor pullback from a high of 41.2x last November… only the second time in history it has exceeded 40x – the other being in late 1999, on the eve of the dot-com crash. Meanwhile, the stock market’s Tobin’s Q rate is around 2.0, the first time in its 120 recorded history it has had a 2-handle. And at 221%, the ratio of the total market capitalization of stocks to U.S. GDP is also at an all-time high, more than double its historical mean of 90%. In every prior instance that these measures have levitated so far above their means, a violent crash has eventually ensued.

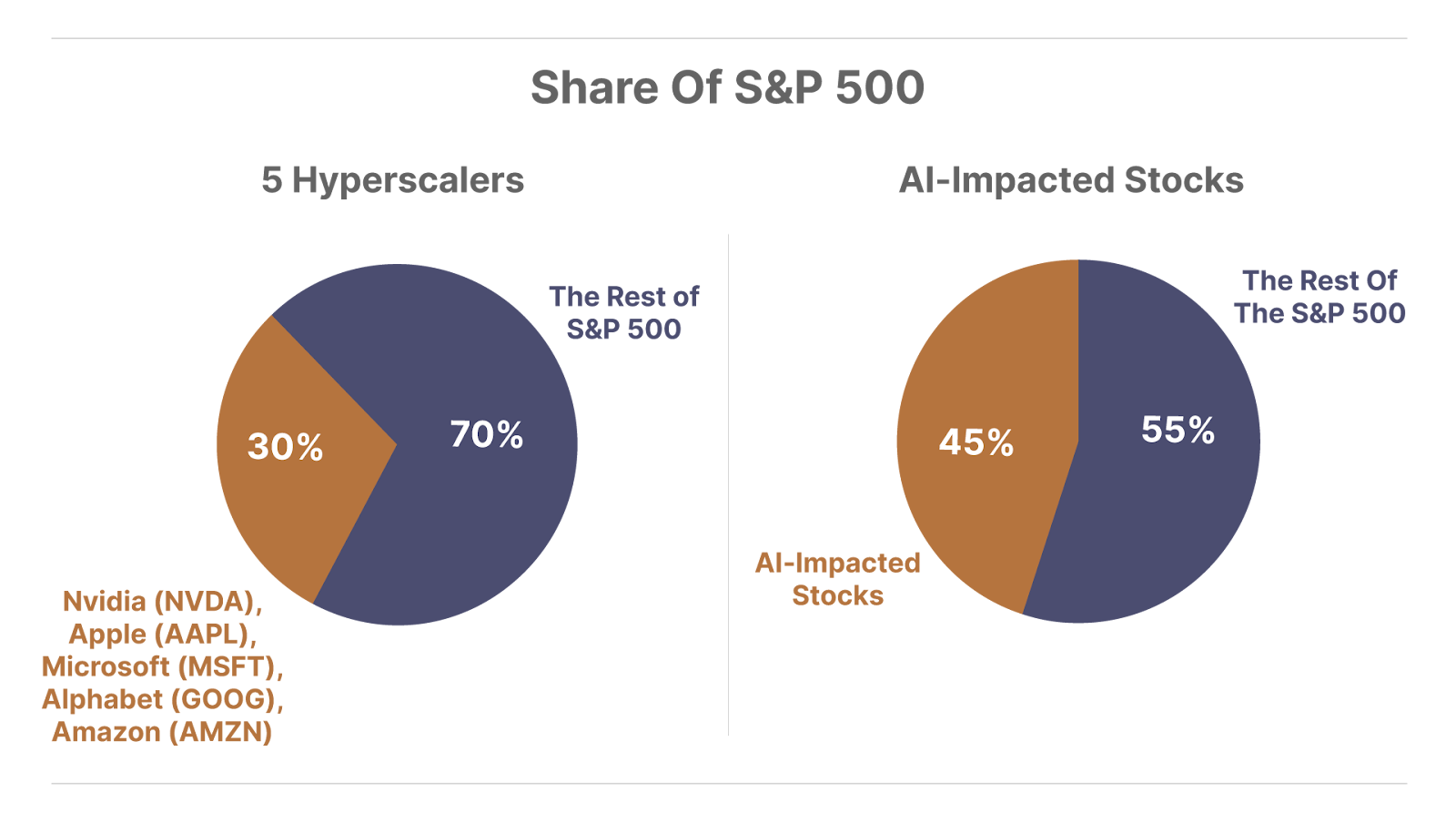

Another way to see how asset prices have detached from fundamentals is to focus on the composition of the stock market’s capitalization. Today, just five stocks – Nvidia (NVDA), Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), Alphabet (GOOG), and Amazon (AMZN) – comprise nearly 30% of the S&P 500’s total capitalization. In the meantime, a recent analysis by the Bank of England places what it calls “AI-impacted stocks” at 45% of the U.S. market capitalization. In plain English, nearly one half of the U.S. large-cap market today is a bet on AI. When so much of the overall stock market’s value rests on one narrative – and on one narrow sliver of stocks – it’s a powerful sign that we’ve detached from fundamentals (to draw from Kindleberger’s definition) and become attached, instead, to a euphoric story.

A final way to perceive the mismatch between asset prices and fundamentals is to zero in on the bellwethers. Let’s take Nvidia, whose chips are the engines of the AI revolution. In October, Nvidia’s market cap crossed $5 trillion, making it the most valuable company in the world. What would be a fair price to pay for a business like this? Historically, the world’s very best businesses – the ones that most closely resemble a permanent annuity stream, their earnings as predictable as a metronome – have traded at 30x their mature earnings. At $5 trillion of market cap, 30x P/E implies about $166 billion in annual earnings for Nvidia once the business levels off from its hypergrowth stage and reaches maturity.

A final way to perceive the mismatch between asset prices and fundamentals is to zero in on the bellwethers. Let’s take Nvidia, whose chips are the engines of the AI revolution. In October, Nvidia’s market cap crossed $5 trillion, making it the most valuable company in the world. What would be a fair price to pay for a business like this? Historically, the world’s very best businesses – the ones that most closely resemble a permanent annuity stream, their earnings as predictable as a metronome – have traded at 30x their mature earnings. At $5 trillion of market cap, 30x P/E implies about $166 billion in annual earnings for Nvidia once the business levels off from its hypergrowth stage and reaches maturity.

In 2025, Nvidia earned nearly 44% of that level – $72.8 billion. Do I think Nvidia will grow its earnings from last year? Yes, absolutely. But do I believe the company will grow its annual earnings 93%, from $72 billion to around $165 billion… and then be able to sustain its earnings semi-permanently at that higher level? No – I think such a scenario is incredibly unlikely.

So whether we focus on the stock market’s valuation, on its value composition, or on key bellwether names like Nvidia, the mismatch between prices and fundamentals today is clear.

Let’s turn to Kindleberger’s other telltale sign of a bubble: excessive optimism and herd behavior.

Measuring euphoria is not as straightforward as measuring stock valuations, because we lack a commonly accepted set of metrics like P/E, price to book, and market cap to GDP. But we can still approach the question in a data-driven way.

For instance: One recent analysis found that 374 of the S&P 500 companies referenced AI on their earnings calls – and nearly 90% of those references were wholly positive, with no discussion of downside or execution risks. This analysis focused on narrative, or the stories companies are telling. We can also see powerful circumstantial evidence of herd behavior in U.S. corporate capex spending. AI-related capex in 2025 topped $350 billion and briefly exceeded 1.2% of GDP – putting it on par with past capex frenzies such as the telecom/internet bubble of the 1990s. When companies talk about AI in one-sidedly positive terms and spend on AI without capital discipline, we know an “AI = future growth” euphoria has taken over.

Financial bubbles end in tears for investors. But let’s also be clear about what identifying a financial bubble doesn’t tell us . . .

First, it doesn’t tell us how long the party will last. As the maxim widely attributed to early 20th-century economist John Maynard Keynes goes,

The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

In the late 1990s, the heyday of the internet bubble, what then Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan memorably described as the market’s “irrational exuberance” ended up lasting much longer than many of the world’s best professional investors – including Warren Buffett and my mentor Julian H. Robertson – believed it would.

Second, identifying something as a financial bubble doesn’t mean that the technology driving the bubble is fake or fraudulent. Railways, the telephone, electricity, the internet – each of these technological leaps instigated a speculative bubble in stocks. They also each permanently transformed the economy and society itself. Julian Robertson was 100% right to describe the dot-com bubble as a speculative mania. And yet internet bandwidth consumption has still increased more than 100x since the late 1990s. The dot-com financial frenzy was a bubble. The internet itself proved to be a world-changing tsunami. So it’s likely to be with AI.

Stan Druckenmiller And Julian Robertson Go Head-To-Head

In 1999-2000, two of the greatest investors of all time – Julian Robertson and Stan Druckenmiller – had a friendly disagreement. They both correctly saw that the Nasdaq was in the spell of a speculative mania. Julian concluded he could profit by shorting the stocks that would inevitably collapse when the bubble burst. Druckenmiller concluded he could ride the mania upward and, relying on his superior skill predicting market turning points, get out profitably just before stocks collapsed.

This was a rare moment when the market would humble both men.

Julian famously shorted a basket of the most notorious dot-com fad stocks, such as pets.com and e-toys. These stocks did eventually decline over 90% from their highs, as he predicted they would. Indeed, many went bankrupt. But Julian was forced out of his shorts six months before the Nasdaq’s collapse as the market squeezed upward. The final phase of a bubble often features a last, parabolic move higher.

While Julian was suffering in agony with his shorts through the market’s final upward squeeze, Druckenmiller bought a massive, $6 billion position in the bubble stocks in early 2000. But uncharacteristically, his market timing instincts failed him. He had bought the stocks too close to the top, and he wasn’t quite fast enough getting out once the market turned. Over six weeks beginning in March 2000, Druckenmiller lost $3 billion – the only time in his career he suffered a setback of this magnitude.

What can we learn from this story?

Navigating a bubble is really treacherous – so treacherous that it humbled two of the greatest professional investors of all time, men who over their careers extracted billions of dollars in profit from the markets with their investment acumen.

More specifically, I think we can also take away two practical lessons that are relevant today:

-

Amid a bubble, conviction about the eventual winners must run deeper than enthusiasm for the theme itself. The hard part isn’t foreseeing that a new technology can transform the world – it’s identifying which handful of companies will survive once the mania recedes.

History is ruthless on this point. When the automobile first burst onto the scene in the early 20th century, America sprouted more than 250 car manufacturers. The opportunity was obvious: engines were going to replace horses. But only a few companies – Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler – endured the inevitable consolidation that followed.

The internet offered a similar spectacle. Many people could see that e-commerce would upend brick-and-mortar retail. Yet for every Amazon that ascended, hundreds of e-toys, pets.coms, and Webvans disappeared. The pattern is constant: Innovation invites excess, and excess invites imitation. The investor’s task is to separate the companies riding the tide from those capable of surviving the undertow. In AI, the same Darwinian contest has already begun. The opportunity is real – but the field is crowded, noisy, and filled with pretenders. To profit, we must be confident that any company we underwrite will not merely enter the race but reach the finish line as one of the winners.

-

Even if we’ve correctly identified a winner, price still matters. There is no point on the timeline of financial history when valuation has stopped mattering for long. As Warren Buffett has reminded generations of investors, “price is what you pay; value is what you get.”

The arithmetic of investing doesn’t bend for good stories: If we pay an absurd multiple for a great company, the best we can hope for is a modest return stretched thin across too many years. The worst is a permanent loss of capital when sentiment normalizes. In every great technological cycle – from railroads to radio, from mainframes to microchips – the enduring fortunes were made not by those who recognized the breakthrough, but by those who had the patience to own it at the right price. Valuation discipline is what separates an investor from a speculator. Amid the euphoria of the AI boom, it’s also what will separate those who keep their gains from those who merely rent them.

Erez’s latest recommendation reached subscribers yesterday, and his next will hit inboxes on Thursday, February 5, 2026, at 4 PM ET. To get full access to those recommendations – plus a list of all open recommendations, “Best Buys,” the watchlist, closed positions, and all archived issues – click here to learn about becoming a subscriber.

Three Things To Know Before We Go…

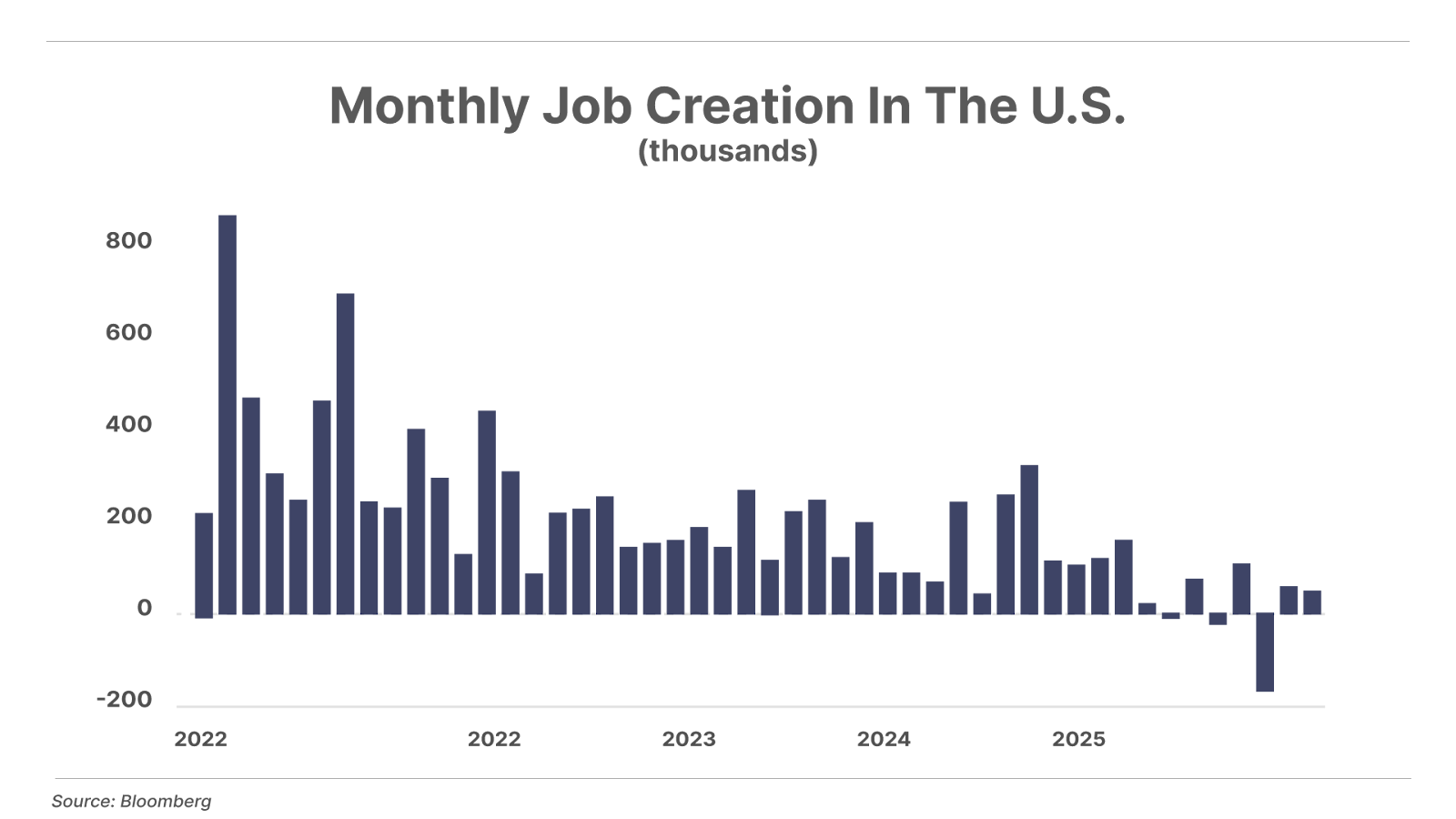

1. The labor market continues to slow. This morning, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) reported U.S. nonfarm payrolls rose by 50,000 in December. This was lower than November’s figures, and well below the roughly 70,000 Wall Street economists had expected. While the unemployment rate did tick lower to 4.4%, the BLS also reported that both the October and November jobs numbers were revised lower by a total of 76,000 jobs. All told, the economy averaged just 49,000 new jobs each month in 2025 versus an average of 168,000 per month in 2024, a 71% decline. Last year’s 584,000 total new jobs also represents the worst year for job growth outside of a recession since 2003.

2. Military spending proposal cements runaway deficits. In a social media post on Wednesday night, President Donald Trump proposed a boost in the 2027 defense budget to $1.5 trillion, a 50% increase over the current $1 trillion budget. This underscores today’s new fiscal reality, where massive government spending increases will continue to outpace tax revenue indefinitely. With no end in sight to the era of multitrillion-dollar budget deficits, it should come as no surprise that gold and silver continue making new all-time highs.

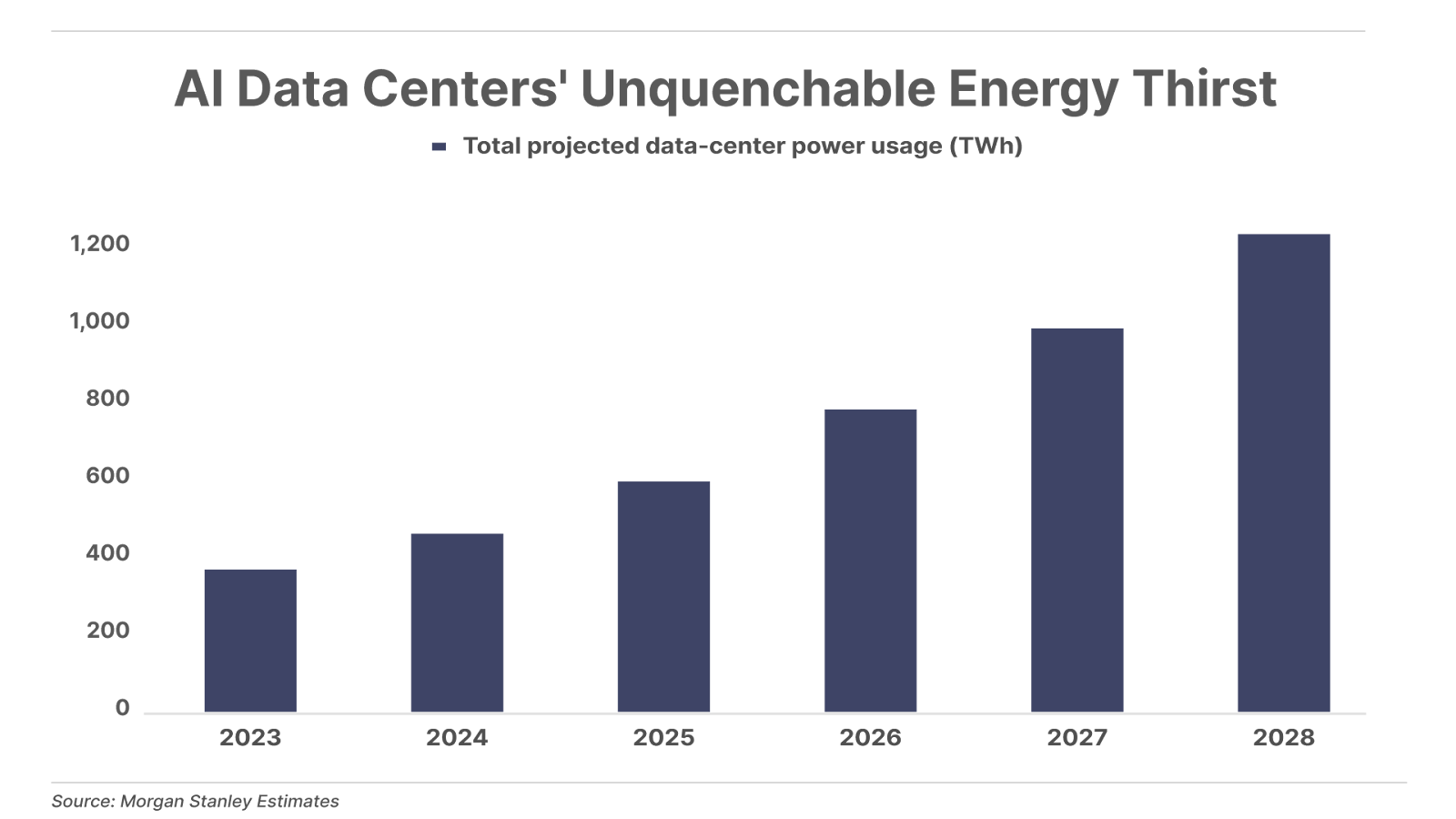

3. AI needs more energy. Electricity demand from AI data centers is set to more than double by 2028, an increase larger than the total annual electricity consumption of several developed nations. The implication – computing is no longer the bottleneck to innovation and growth. Energy is, and AI growth is becoming increasingly dependent on who secures reliable, scalable power. In yesterday’s Complete Investor, we laid out why this trend is becoming increasingly critical – and identified the specific companies best positioned to deliver the reliable, scalable energy that will power the AI-driven economy.

And One More Thing… Poll Results – Gold Medal For Gold

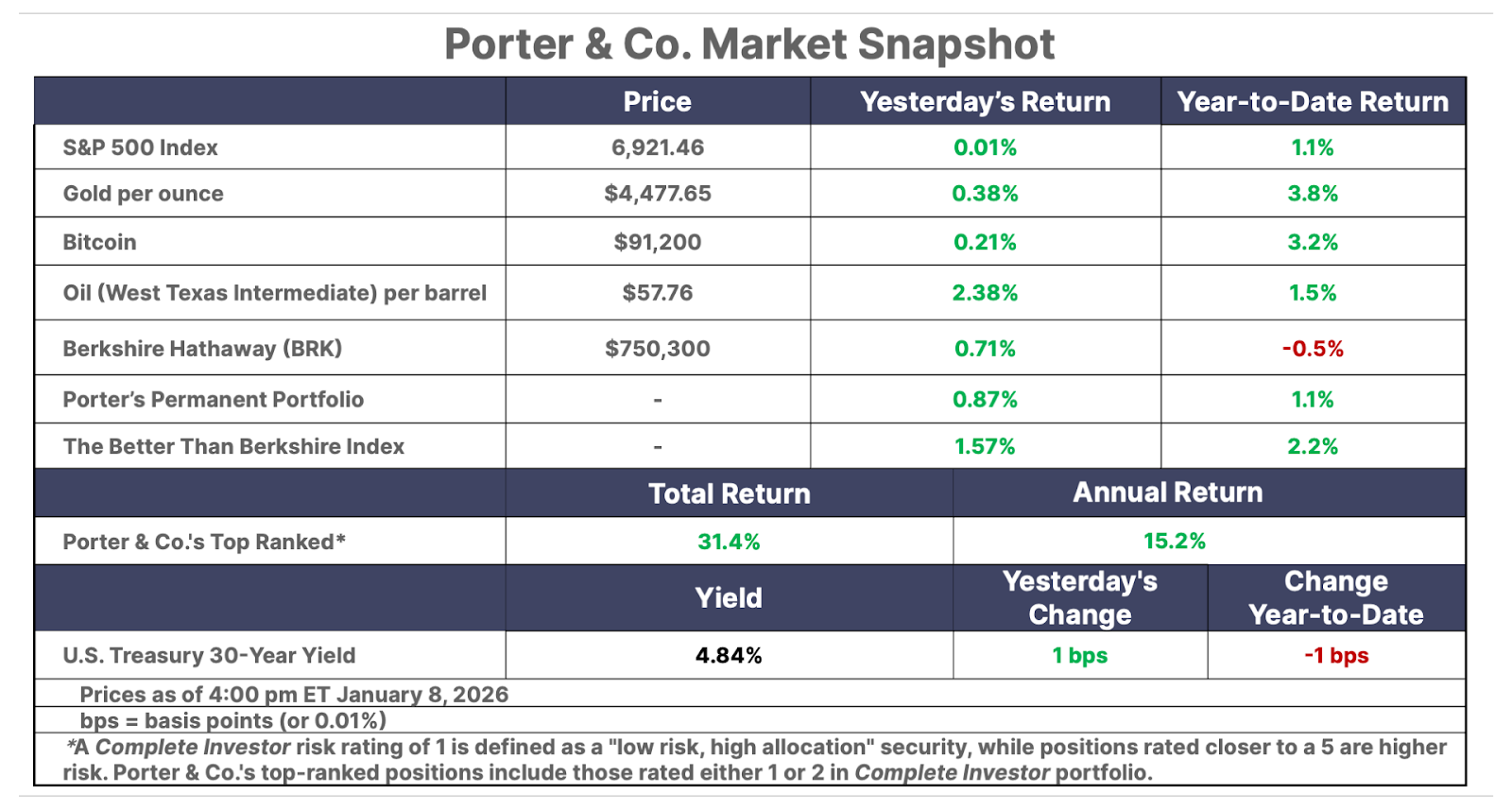

In Wednesday’s Daily Journal, we asked readers which asset class – gold, Bitcoin, or U.S. equities – would have the best return at the end of 2026. The vast majority of survey takers – 65% – think gold will outperform the other two, with 32% believing Bitcoin will be strongest, and just 3% going with U.S. equities, represented by the S&P 500… Gold jumped above $4,500 per ounce for the first time today.

Tell us what you think about today’s Journal or any other topic: [email protected]

Good investing,

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, Maryland

Please note: The investments in our “Porter & Co. Top Positions” should not be considered current recommendations. These positions are the best performers across our publications – and the securities listed may (or may not) be above the current buy-up-to price. To learn more, visit the current portfolio page of the relevant service, here. To gain access or to learn more about our current portfolios, call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895 or internationally at +1 443-815-4447.

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.