How to Own “Walmart” At A Big Discount

A Generational Buying Opportunity Is Approaching

Jerónimo Arango hadn’t had many “lightbulb moments” in his life. He hadn’t needed to.

The spoiled eldest son of a Mexican textile magnate, he’d spent his 20s leisurely touring the Americas and taking art and literature courses. Then, one afternoon in 1956, while exploring New York City, he noticed a Fifth Avenue queue that wrapped twice around the block.

Curious, he joined the line and found out he was waiting to get into Korvette’s, New York’s hottest discount department store. Actually, at the time it was New York’s only discount department store.

Korvette’s wasn’t where rich kids shopped. It was a mix of furniture, clothing, audio equipment, luggage, jewelry, and appliances – all thrown together higgledy-piggledy in a giant warehouse space and heavily discounted. Korvette’s got around the U.S.’s strict anti-discounting laws for retail stores by claiming it wasn’t a retail establishment, but a cooperative… so it handed out a “membership card” to every person who walked in the door.

The ploy worked: Korvette’s was raking in $2,500 per square foot of floor space… in 1956 dollars. (For perspective, in the 1960s, the flagship Marshall Fields department store in Chicago brought in about $12.50 per square foot.)

Somewhere between the lamps and the lingerie, Jerónimo Arango had his first-ever genuine brainstorm…

As soon as he’d wrestled his way out of the crowd of bargain hunters, he found a phone and called his younger brothers Manuel and Plácido, back home in Mexico.

“For 30% to 40% off, people [are] willing to be mistreated,” he told them bluntly. Then he suggested they all go into business together and start a deep discount store like Korvette’s, south of the border. His two hermanos eagerly agreed.

Mexican bargain hunters were apparently just as keen to be “mistreated” as New Yorkers. Without the laws and regulations that would continue to hamper discount stores in the U.S., Jerónimo’s new Mexican chain – founded in 1958 and christened Cifra – flourished, becoming the largest supermarket chain in the country by the early 1990s. (Sadly, Korvette’s didn’t fare nearly as well, with a series of poor business decisions leading it to declare bankruptcy in 1980. However, its membership-card scheme later served as an inspiration for Costco Wholesale and Sam’s Club.)

Arango created a tiered system of higher- and lower-end discount stores targeted to different regions of Mexico… but, no matter what you bought, the price cut stayed the same. Everything at Cifra – food, dry goods, appliances – was 20% or more off the list price (as opposed to the 40% or more markup you’d find at regular department stores).

Thanks to stockpiling cheap staples that remained heavily in demand, Cifra survived and even thrived during Mexico’s 1980s financial crisis – growing its sales by 20% during every year of that decade, with its stock tripling in value by 1989. By the early 1990s, it operated 179 stores and boasted the best sales per square foot in the country.

Odds are, you’ve never heard of Cifra, though – because after three decades of spectacular growth, it signed a joint-venture agreement with American retail giant Walmart (WMT) in the 1990s. And thereby hangs a perplexing tale…

Where Have All The Cowboys Gone?

After signing the agreement with Cifra in 1991 and collaborating on several successful combination Walmart and Cifra stores, Walmart bought a controlling stake in 1997 and renamed Cifra “Walmart de Mexico” (Walmex). Then, wisely, the company went hands-off. Walmart leadership asked Jerónimo Arango (by then, one of Mexico’s top three richest men) to keep running Walmex with the same strategies that had worked so well for Cifra.

Today, Walmart owns 70% of Walmex, and the remaining 30% of the shares are publicly traded on the Mexican stock exchange (U.S. investors can buy shares directly on the Mexican exchange, or purchase shares through an American Depositary Receipt on over-the-counter U.S. exchanges through the WMMVY ticker.)

The Arango magic touch continued to produce gold. (Arango died in 2020, but his vision still shapes the company.) Today, Walmex operates 3,600 Walmart and Sam’s Club locations in six Latin American countries, including Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

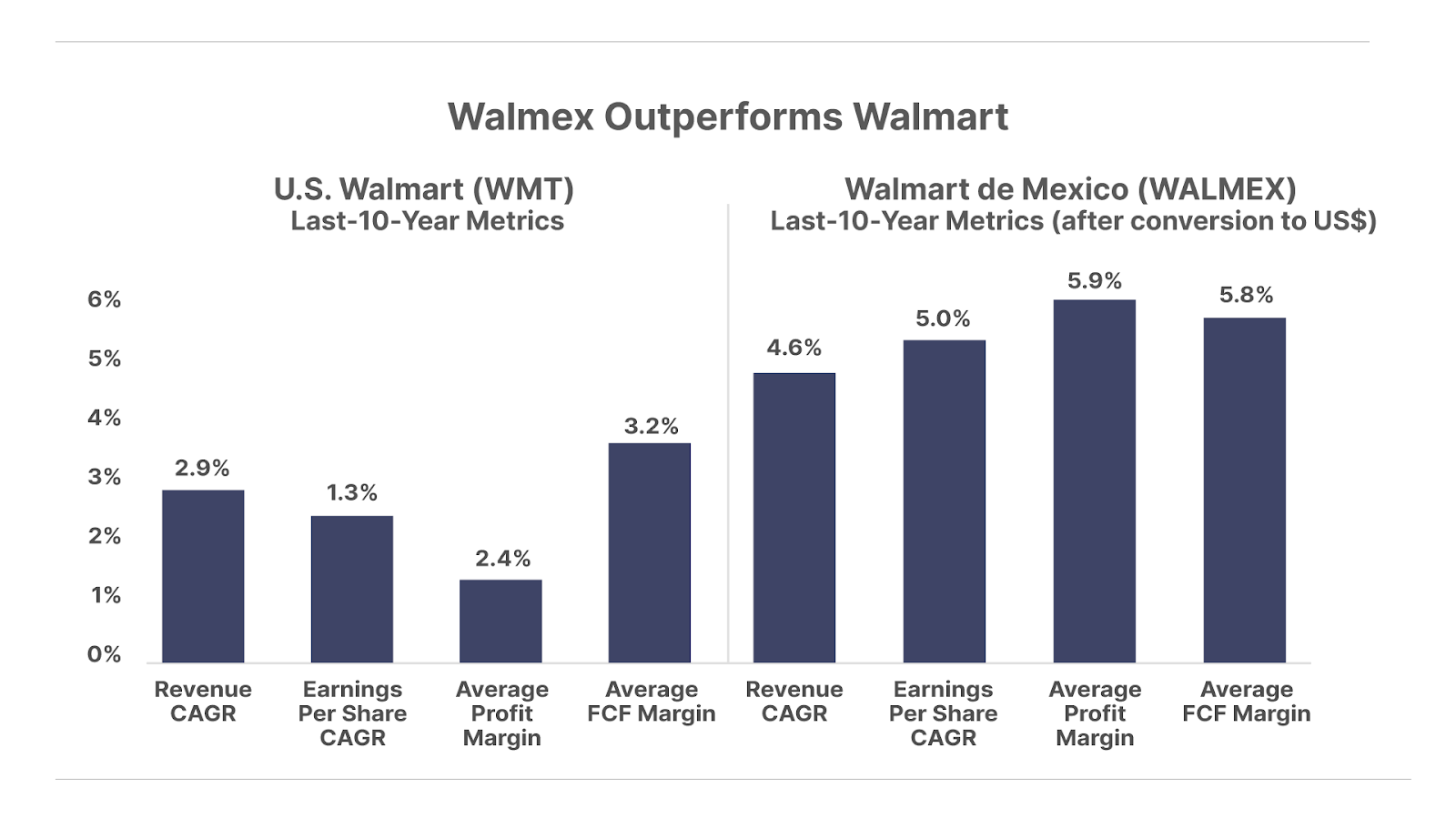

Interestingly, based purely on the fundamentals, Walmex is actually outperforming Walmart itself. Take a look at these numbers…

Walmex is growing revenue 60% faster than Walmart, and generates twice as much net income and free cash flow on every dollar of sales. Moreover, Walmex’s dividend yield is a healthy 4% compared to Walmart’s paltry 0.9%.

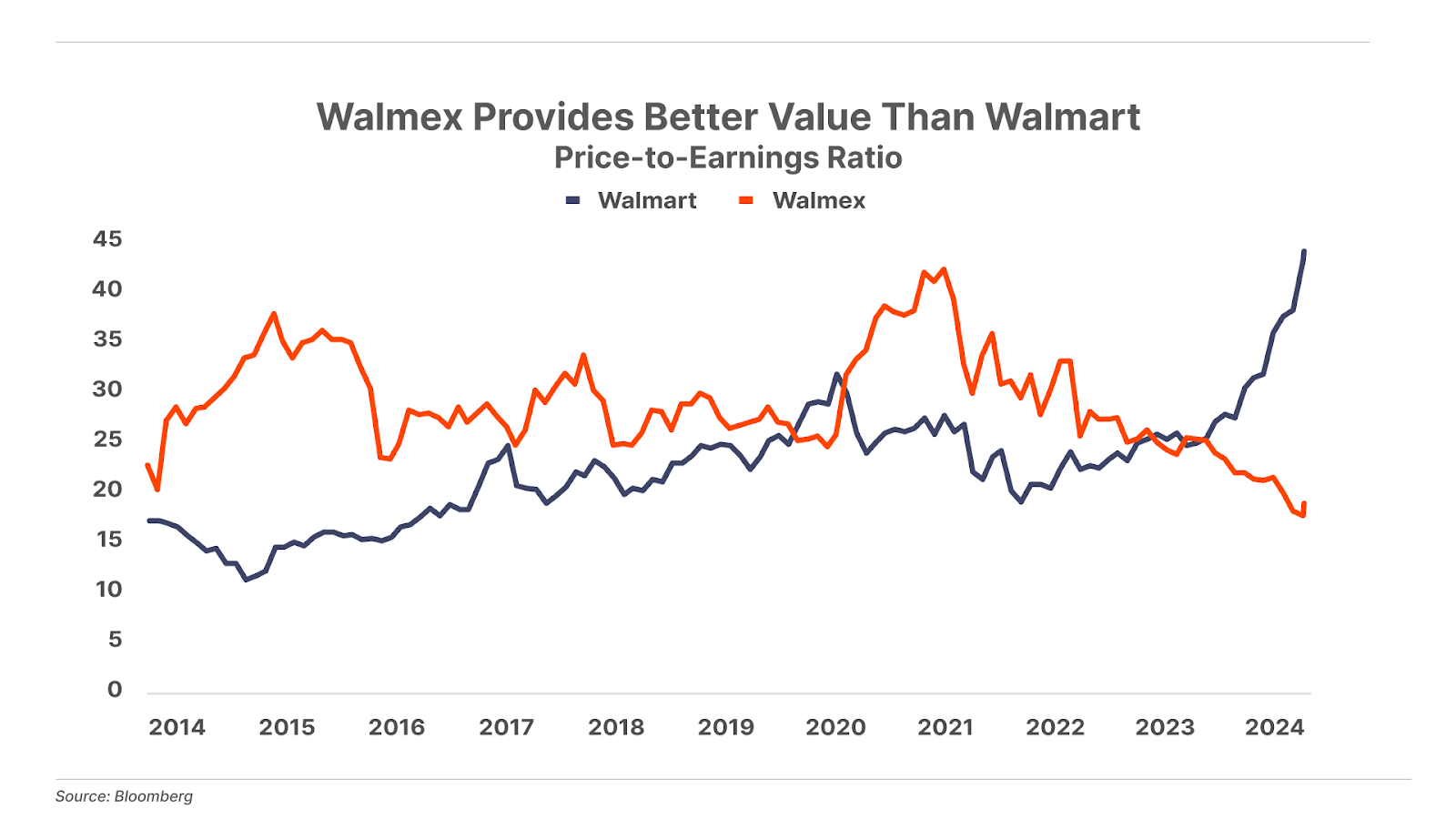

Historically, Walmex has commanded a premium valuation over Walmart for exactly these reasons. But right now, Walmart shares are booming (up 75% year to date)… while Walmex has plunged (down 40% so far this year).

Remarkably, this underperformance is occurring despite the relative strength in the Mexican economy.

In 2023, for the first time in two decades, Mexico edged out China as America’s largest source of imports. And given Mexico’s growing trade with the U.S., all signs indicate its economy is set for a multi-decade boom.

So what explains this unusual underperformance?

Mexican stocks in general have been hit hard this year for a variety of reasons – including an unwind of the Japanese yen carry trade (borrowing one currency to invest in another) and recent Trump tariff headlines – that are likely to have little lasting impact on the broad economy or earnings growth of Mexican companies like Walmex.

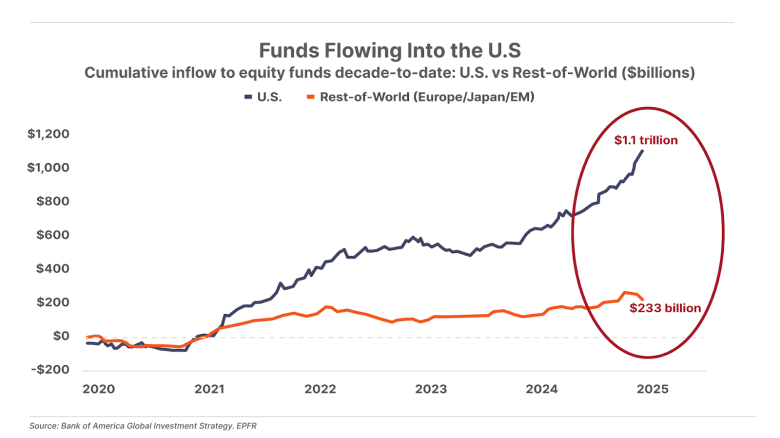

Meanwhile, the confluence of unprecedented fiscal deficits, relatively easy financial conditions, and an artificial intelligence (“AI”)-fueled tech boom have driven massive inflows into U.S. stocks.

U.S. equity funds have experienced inflows of nearly $450 billion year to date. That’s more than any prior year on record – and hundreds of billions more than the pre-COVID average. And because of the predominance of market-cap weighted indexing, these flows disproportionately benefit large-cap companies like Walmart.

This divergence has driven the valuation spread between Walmart, trading at a decade-high 43x earnings, and Walmex, trading at a decade-low 19x earnings, to an all-time extreme.

Given this combination of fundamental strength, low relative valuation, and the potential boost of a strengthening Mexican economy, we believe Walmex is likely to dwarf the returns of Walmart over the next several years.

However, this rare opportunity isn’t exclusive to Walmex… or even Mexican stocks in general. Rather, it’s just one example of how the U.S. market has become wildly overvalued while foreign markets have languished.

The World Is On Sale

Investors around the world have been plowing record amounts of capital into U.S. equities in recent years.

This is a zero-sum game: when money flows into one market, it doesn’t go into others.

All told, more than $1 trillion has flowed into U.S. equity funds over the past five years – roughly four times the total inflows into funds that invest in every other public market in the world combined.

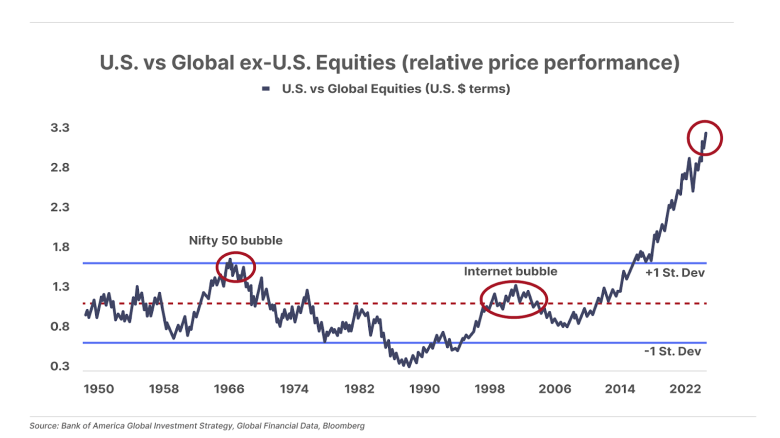

As a result, U.S. markets have dramatically outperformed the rest of the world like never before.

The relative outperformance of U.S. stocks has stretched to more than three standard deviations above the long-term historical mean.This is more than double the extremes seen in the prior two U.S. stock market manias – the 1960s Nifty 50 bubble and late 1990s dot-com boom – each of which were followed by a sharp reversal which saw the rest of the world outperform for the next several years at least.

This recent outperformance of the broad U.S. market has caused global equities valuations to diverge similarly to the Walmart and Walmex comparison we shared earlier. The price-to-earnings ratio of the broad U.S. equity market is roughly 50% higher than the rest of the world… price-to-sales is nearly 70% higher… and price-to-book is more than 90% higher.

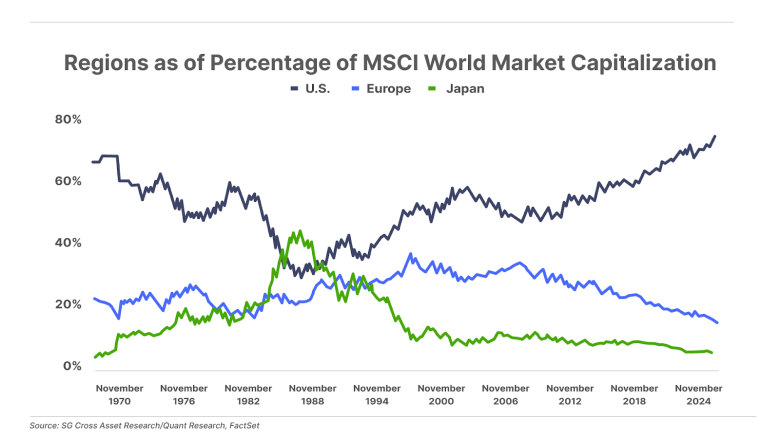

The past decade of accelerating outperformance has also pushed the U.S. share of global stock markets to an all-time high. The U.S. now accounts for 74% of the MSCI World Index market capitalization. The next largest market-cap country – Japan – accounts for just 7% of the index. And the combined markets of Europe – including the UK, France, Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Denmark, Belgium, Ireland, and Portugal – account for only 15% of global market cap.

We are in the midst of a generational bubble in the U.S. that has left the rest of the world behind. And it’s setting up a similarly rare opportunity in the equities of those left-for-dead markets.

Of course, we can’t know for certain when this mania will finally end. But we do know it eventually will… and when it does, it will usher in a multi-year period of mean reversion – where valuations will move back toward their historical norms (likely overcorrecting along the way).

When this happens, U.S. stocks will perform poorly, while relatively cheap stocks in the rest of the world could soar… particularly the highest-quality, capital efficient businesses with superior fundamentals.

We expect to make these stocks a regular focus of our research in the years ahead, and paid-up subscribers to The Big Secret on Wall Street will be the first to know when we do. In fact, we’ve already identified one of these compelling opportunities for subscribers today…

This little-known European company is a clear leader in a booming industry, with nearly 40% global market share… is highly capital efficient with better than 50% net income margins… and is growing revenue at 15% a year. Yet it currently trades at just 15x earnings – its lowest multiple in history – making it one of our top 3 “best buys,” as seen in our last issue of The Big Secret on Wall Street.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, get immediate access to this recommendation – and the full Big Secret portfolio – right here.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD