Eventually, people will stop worrying about the viability of private banks like Credit Suisse, and start worrying about the viability of central banks and the currencies they issue. The coming loss of faith in government-issued currency will cause the ultimate bank run – a run on central banks.

A Run on Central Banks

On March 22, 2021 Bill Hwang was worth $20 billion… rich enough to be one of the 100 wealthiest people on Earth.

Three days later, he would have had to ask for a loan to buy a cappuccino.

It was the fastest implosion of individual wealth in Wall Street history.

Before he made headlines for all the wrong reasons, few people outside the financial world knew Bill’s name. He grew up poor, as the son of a pastor in South Korea. He immigrated in 1982 with his widowed mother to the U.S., and went on to earn an MBA at Carnegie Mellon University. He set his sights on Wall Street, and eventually was hired as an analyst at Tiger Management, run by famed hedge fund manager Julian Robertson.

Bill worked his way up the ranks at Tiger Management, at the time one of the titans of the hedge fund industry. By the early 2000s he became a manager of his own offshoot fund, Tiger Asia, which peaked at $10 billion in assets. Despite his success, Bill lived modestly in the Jersey suburbs, drove a Hyundai to work, and donated vast amounts of money to Christian charities.

Then the trouble began.

Bill ran afoul of the SEC for insider trading and share price manipulation in 2012. He was forced to shutter the Tiger Asia fund and pay a fine of over $60 million. He then “retired” at the age of 48, with a tidy $200 million in personal wealth.

He used that money to launch Archegos Capital Management, a family office – which is kind of like a friends-and-family hedge fund.

Hwang knew who to talk to at some of Wall Street’s biggest firms – Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Deutsche Bank, to name a few – so that he could get the same kind of portfolio jet fuel that he’d had access to before: Massive leverage.

If a normal investor wants to borrow from his brokerage to buy more shares than the cash in his account allows, he can borrow… up to around 2-to-1. That means that with $100 in his account, he could buy $200 worth of shares.

Former hedge fund managers running family offices live in a different universe, though. Using leverage, as well as derivative instruments that were like leverage on steroids, Hwang was able to get leverage of as much as 20-to-1. That means that with $100, he could buy $2,000 worth of share exposure… that is, he could do the equivalent of putting down $5 to buy a $100 stock.

That’s great on the way up. But it’s less good on the way down. If the $100 stock fell to $95, Hwang’s broker would require more collateral. If he couldn’t deliver more cash, the lender would sell off part of the underlying stock in what’s called a margin call.

For a while, things went well. One big bet on streaming company Netflix cleared $1 billion in profits for Archegos. By 2017, Hwang had grown his original $200 million in starting capital by 20-fold to $4 billion.

By early 2021, Bill Hwang had built up his personal fortune to $20 billion. And he’d leveraged that $20 billion into a $100 billion trading portfolio, with concentrated bets on a range of media companies including Tencent Music Entertainment (NYSE: TME), Discovery (NYSE: DSCA), and Paramount Global (NYSE: PARA), formerly Viacom.

There was just one problem: this steep leverage meant that a relatively small decline in the portfolio holdings would wipe out all his capital, leaving brokers on the hook for any additional losses.

While Hwang had a who’s-who of Wall Street on speed dial, one of the more reliable dealers of Hwang’s drug of choice, leverage, was Swiss bank Credit Suisse. CS was less concerned with his checkered history of insider trading, and much more interested in the big commissions earned from Archegos’ active trading style, which generated tens of millions of dollars in fees.

That lean-in attitude towards risk would come back to bite Credit Suisse in the backside when Bill Hwang’s lucky streak finally snapped, on Monday, March 22, 2021.

That was when Viacom – one of Archegos’ major holdings – announced a $3 billion share offering after the close of trading on Monday. The next day, Viacom shares fell 9%, followed by another 23% plunge on Wednesday.

Archegos’ $20 billion in equity capital vanished like cotton candy in the rain. Brokers who previously couldn’t get enough of lending to Hwang abruptly found themselves on the brink of losing billions of dollars.

The bankers started calling Bill, urging him to sell shares and take the loss. He refused.

Their only recourse was to issue a margin call and force a sale of assets (as seen in the climactic “orange juice futures” scene of the 1983 Eddie Murphy classic, Trading Places). As part of any standard margin lending agreement, if the value of the portfolio declines to the point of putting brokers at risk of losing money, the broker can force a sale of assets to protect the value of the borrowed funds.

But this kind of situation begets winners and losers. Bill Hwang had massive positions in a concentrated basket of stocks, so a forced sale into an already-depressed market would crush prices (and increase brokerage losses) even further.

Hwang’s bankers were fight-to-the-death competitors, but these were extraordinary circumstances. They called a temporary truce and held an emergency meeting on Thursday.

The brokers faced a classic prisoner’s dilemma: If everyone remained calm and no one sold, prices could – potentially – rebound and allow everyone to escape unscathed. But if just one bank panicked and sold, the advantage would go to the first seller – at the expense of the others.

The Morgan Stanley bankers’ strategy recalls a famous line from another classic Wall Street film, Margin Call: “It’s not panicking if you’re the first one out the door.”

Breaking with its Wall Street brethren, Morgan Stanley moved first, unloading $5 billion in Archegos holdings into the market on Thursday afternoon, escaping with their margin loan intact. Goldman Sachs followed, with over $10 billion in pre-market sales on Friday morning.

Credit Suisse, on the other hand, wanted to wait out the storm. They were hoping that when the smoke cleared, prices would rebound, and Archegos’ positions would move back into a profit, allowing the bank to avoid taking a loss on their margin debt.

But hope, as they say, is not a strategy. The large sell orders from the brokers who sold first further crushed the prices of the shares held by Archegos, wiping out Bill Hwang’s equity cushion, and putting him deeply in debt to his remaining brokers.

In the end, those who sold first – including Goldman, Deutsche Bank, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo – avoided taking any losses.

Credit Suisse ultimately booked a $5.5 billion loss on the margin loans from Bill Hwang’s busted trades. (By comparison, the bank as a whole earned $6.7 billion in the prior year.) Credit Suisse later shut down the unit that worked with outside hedge funds like Archegos, and clawed back $70 million in stock option compensation from employees involved with the debacle. A review by an outside law firm noted that Credit Suisse “was focused on maximizing short-term profits and failed to rein in and, indeed, enabled Archegos’s voracious risk-taking.”

Credit Suisse has a history of making bad (sometimes, criminal) decisions.

For instance, CS marketed billions of dollars in debt from the now-defunct Greensill Capital as “low risk.” Greensill filed for bankruptcy in March 2021. In February of this year, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) found the bank’s activities regarding Greensill reflected “a serious breach of Swiss supervisory law.”

In October 2021, Credit Suisse was fined $547 million in criminal and civil fines for a fraudulent $850 million loan in Mozambique. Investigators discovered that the Mozambique loan was designed to funnel millions in kickbacks to Credit Suisse executives and government officials.

That same month brought the infamous “spygate” scandal to the Swiss bank, when FINMA released findings that the bank had spied on seven individuals including members of the board, previous employees, and other parties involved with Credit Suisse’s banking operations.

So it’s not surprising that Credit Suisse is the latest casualty in this month’s rolling series of bank failures. Last Wednesday, we warned paid subscribers of The Big Secret on Wall Street that “The SVB Crash Was Just The First Domino”.

It didn’t take long for this prediction to pan out.

(Oh, by the way… Bill Hwang and several of his Archegos coworkers are awaiting an October 2023 trial for racketeering, stock price manipulation, and wire fraud.)

A Play-by-Play Repeat of Bear Stearns

Credit Suisse has struggled with a slow decline in assets and negative profitability in recent years, including a net loss of $1.9 billion in 2021 followed by a loss of $8 billion in 2022. The situation became more acute in October of last year, when rumors began circulating on social media about the bank’s health. The bank’s wealthy clients began withdrawing money en masse, with deposits falling 40% last year to $252 billion, and the bank’s asset base shrinking by 30% to $571 billion.

The deposit flight accelerated in the wake of the SVB bank failure in the U.S.

Then, last Wednesday, the Chairman of the Saudi National Bank – Credit Suisse’s largest investor – said he would “absolutely not” increase his stake in CS. Credit Suisse shares plunged to new record lows on the news. The following day, the Swiss National Bank committed to a $50 billion credit facility to help shore up Credit Suisse’s liquidity.

But depositors were spooked, and began withdrawing deposits at an average of over $10 billion per day following the news. And on Friday, Reuters reported that “at least four major banks” began pulling back on loans with Credit Suisse, fearing an imminent default.

Over the weekend, the situation came to a head: Swiss financial authorities engineered a “shotgun wedding” between Credit Suisse and its Swiss rival UBS.

In contrast to Credit Suisse, UBS is known in the banking industry for a more conservative approach towards managing risk. This helped UBS grow its asset base from $960 billion in 2018 to $1.1 trillion last year, compared with Credit Suisse’s declining asset base from $780 billion to $571 billion over the same period.

For just $3.2 billion, UBS acquired Credit Suisse’s $571 billion in assets, along with the bank’s wealth management business, which invests around $1.4 trillion in assets for high-net worth individuals around the world.

The purchase price was a more than 50% discount from where Credit Suisse shares closed the prior Friday, and a 99% decline from Credit Suisse’s all-time high share price in 2007. The transaction also wiped out roughly $17 billion in debt obligations that UBS won’t be paying to former Credit Suisse convertible bond holders.

In the words of the old jazz standard, “It seems I’ve heard that song before.” The Credit Suisse debacle is eerily similar to the fate of former Wall Street bank Bear Stearns in March 2008.

Bear Stearns was over-exposed to the subprime mortgage market in the mid-2000s. It was a leading player in the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market, which involved buying mortgage loans (often of dubious quality) and repackaging those loans into MBS for sale to investors. The problems arose when default rates began spiking, and the demand for the MBS products that Bear was selling dried up.

The first signs of trouble appeared when two multi-billion dollar hedge funds went bust in July 2007, the Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Fund and the Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Enhanced Leveraged Fund.

By March 2008, with the subprime meltdown accelerating, Bear Stearns was nursing massive losses on its mortgage exposure. Meanwhile, the other big banks that had lent Bear Stearns money began pulling back on the amount of credit they were willing to extend. On Tuesday, March 11, the Federal Reserve opened up a $50 billion lending facility to help Bear Stearns and other struggling banks shore up liquidity. (Eerily, this is exactly the same figure recently offered to CS by the Swiss National Bank.)

The move backfired, and the bank’s investors and counterparties began pulling more of their capital away from Bear Stearns. On Saturday, March 15, the Federal Reserve called an emergency meeting – its first in 30 years – where it orchestrated a takeover effort by J.P. Morgan.

On Sunday evening, the board of directors at Bear Stearns agreed to a last-minute fire sale to J.P. Morgan for $2 per share – 93% below where Bear Stearns shares closed on the previous Friday (further negotiations eventually raised the bid to $10).

Markets cheered the bailout effort, and the S&P 500 rallied 15% into the summer of 2008. But the rot ran deep: the failure of Bear Stearns was just the opening act to the market collapse that would occur in fall 2008, when the contagion spread into AIG, Lehman Brothers and the broader financial markets.

Bear Stearns was just the start of the 2008 crisis. And today, the dramatic collapse of Credit Suisse is merely the opening salvo of the 2023 financial meltdown.

How did we get here again? Over the past 15 years, policymakers have erected a byzantine labyrinth of regulatory and monetary safeguards designed to prevent a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis. But none of that matters in the face of the universal principle of financial thermodynamics:

Risk cannot be eliminated, only transferred.

“Too Big to Fail”…But Not Really

The top 30 largest banks in the world – which, until last Sunday night, included Credit Suisse – are designated “Global Systemically Important Banks” (G-SIBs). Governments will always bail out these banks, since they each play a critical role as counterparties throughout the global financial system.

But anytime governments classify banks as “too big to fail,” they hand them a blank check to act irresponsibly. (After all, why shouldn’t you go drag racing in the Porsche if Daddy will buy you a new one when you crash?) And when big banks act irresponsibly enough, they can take large swathes of the financial system down with them.

Daddy might buy you a new car, but he can’t do anything about that heirloom oak tree you hit.

Credit Suisse, like its fellow G-SIBs, carries huge liabilities via its derivatives exposure. These derivatives include things like interest rate swaps – “insurance” instruments used by big banks to hedge against spiking interest rates. (More on how those work in a moment.)

On December 5, 2022 the Bank for International Settlement released a report detailing how non-U.S. banks like Credit Suisse had amassed a “staggering” $39 trillion of derivative liabilities, equal to “10 times their capital.”

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) recently found that as of Q3 2022, the top four U.S. banks held $172 trillion in derivatives exposure, or more than 20 times their combined asset base of $8 trillion.

Even more alarming, most of these derivatives transactions do not take place on a public exchange where regulators can monitor them. According to the OCC, 58.3% of derivative transactions are private “over-the-counter” purchases. This means that two banks can strike a complex, multi-billion dollar derivatives deal in a two-minute phone conversation.

This helps explain why the fire sale price UBS received for Credit Suisse wasn’t enough to seal the deal. Wary of Credit Suisse’s outsize derivatives exposure, UBS also demanded that the Swiss National Bank provide a $100 billion liquidity backstop for the transaction, along with $9 billion in guarantees against future losses from the Swiss Government.

For perspective, the entire Swiss economy is $800 billion. A similar-sized backstop for a U.S. bank would have translated into nearly $3 trillion.

Where will the Swiss National Bank come up with the money to finance such a backstop? With newly issued money created from thin air, of course.

In a CNBC interview, the CEO of financial research firm Opimas Octavio Marenzi provided his take on the deal:

“The Credit Suisse debacle will have serious ramifications for other Swiss financial institutions. Switzerland’s standing as a financial center is shattered. The country will now be viewed as a financial banana republic.”

Unfortunately, Switzerland won’t be the only country to slip on a banana peel in the near future.

The Trillion-Dollar Ticking Time Bomb That No One is Talking About

Last week, we explained to paid subscribers how “regulators spent the last decade safeguarding against every possible downside scenario, except the one that actually happened: trillions of dollars of low-yielding assets running headlong into a sharp rise in interest rates.”

We also explained why the SVB failure was not an isolated incident, and that investors should brace for more dominoes to fall:

“The same fundamental problem that struck Silicon Valley Bank – buying a lot of bonds at record low interest rates, and suffering big paper losses when rates moved higher – is endemic throughout the banking sector.”

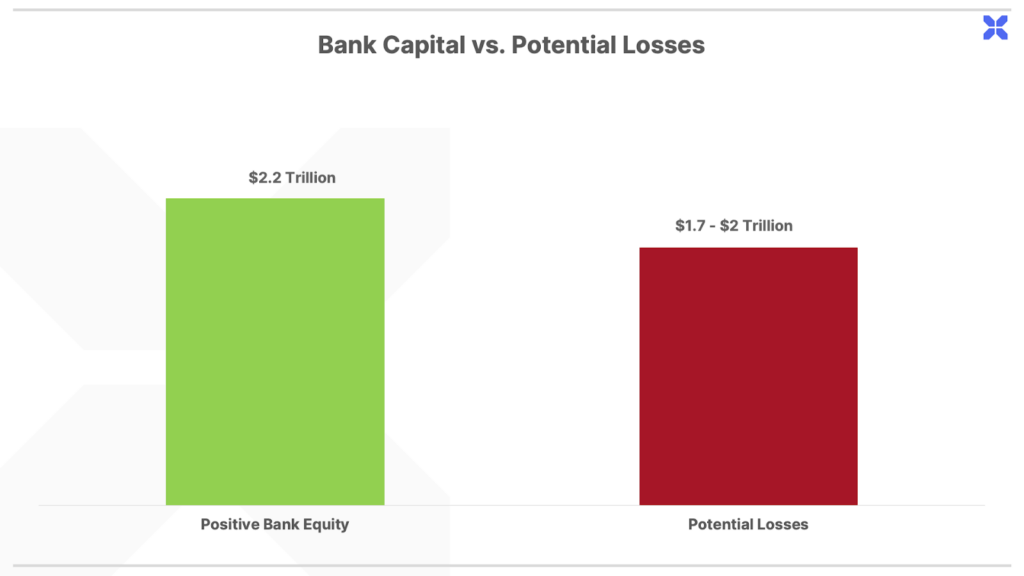

A study published on March 13 estimates that the rapid rise in interest rates since 2022 has contributed to total losses of $1.7 – $2 trillion among the assets held on U.S. bank balance sheets. For a frame of reference, the total capital buffer (the amount of positive bank equity to offset these losses) is $2.2 trillion.

In simple terms, if the banking system were forced to liquidate their current asset holdings of bonds and loans, the losses would wipe out between 77 – 91% of their capital.

But that $2 trillion in losses is only the tip of the iceberg.

So far, the conversation has focused on banks like SVB that took excessive risk by failing to hedge against the impact of higher interest rates. But the far larger problem lies with the banks that did hedge interest rate risk… and the counterparties on the other side of that trade.

Specifically, we’re talking about an instrument known as an “interest rate swap” which banks can buy to protect their portfolios of low-yielding assets against a sharp move higher in interest rates.

Interest rate swaps are like insurance contracts for the financial system. When a bank enters into this type of contract, it locks in a fixed value on a bond or other fixed income instrument that would otherwise fluctuate in value as market interest rates change (i.e., protects against bond prices falling when interest rates rise).

Loosely regulated smaller banks don’t use this type of sophisticated derivative very much – but the “too big to fail” G-SIBs snort them like cheap cocaine.

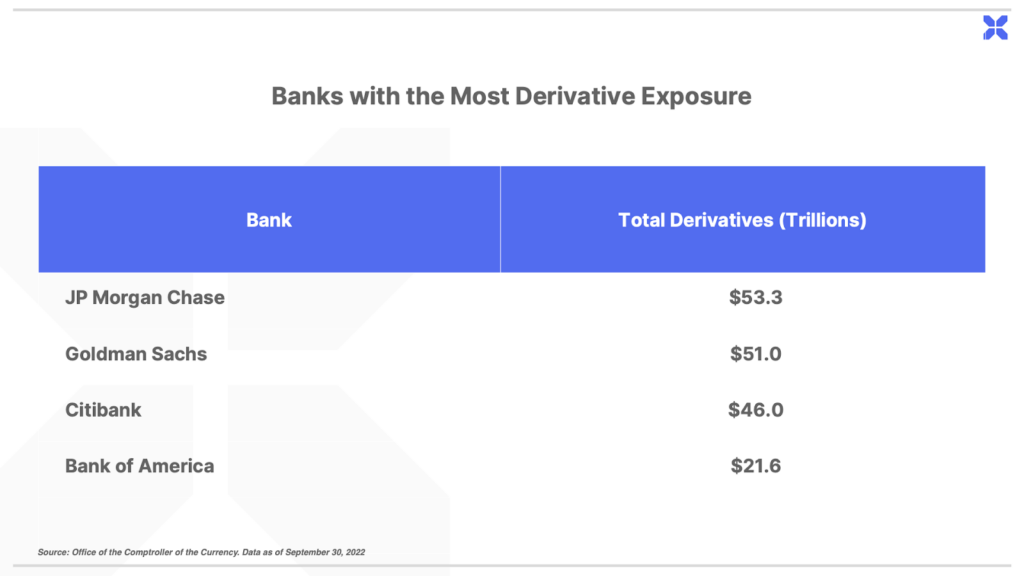

The derivatives exposure among the top U.S. banks, which include interest rate swaps, currently stands at $54.3 trillion at J.P. Morgan, $51 trillion at Goldman Sachs, $46 trillion at Citibank and $21.6 trillion at Bank of America.

But as we mentioned previously, the majority of these derivative trades take place “over the counter” instead of through regulated exchanges. This means regulators and the investing public are flying blind here. No one knows which banks are making these deals with each other…or which ones are the most risky. The only thing we do know is that the size of these derivatives portfolios are on the order of hundreds of trillions of dollars around the globe.

And bad things will happen if the counterparties to these trades go bust.

When a vulnerable G-SIB like CS goes down, the impact can reverberate across the global financial system. That’s because a bank like CS may be the counterparty on the other side of another bank’s derivative trades. And if CS defaults and can’t make good on its side of the trade, then CS’s counterparty bank becomes exposed to losses.

Last week, we saw other banks stopped their counterparty trading with CS when they became concerned CS would go under, in which case CS wouldn’t be able to honor their side of any counterparty trades.

When financial contagion spreads to the point of taking down G-SIBs, there’s nowhere to hide – because even banks that used derivatives responsibly to hedge against rising interest rates may have been trading against reckless counterparties. Those counterparties could now be facing trillions of dollars in losses – and that puts the “responsible” banks on the other side at risk.

This is exactly the kind of risk that nearly took down the global financial system in 2008. Back then, the derivatives that blew up were credit default swaps against mortgage bonds. And when the reckless sellers of those derivatives defaulted on their obligations as mortgage bonds went bust, governments and central banks were forced to backstop the busted trades to the tune of trillions of dollars.

Again, no one knows what lurks beneath the surface of hundreds of trillions of dollars in the opaque, over-the-counter derivatives market. But what we do know is that when UBS took a look under the hood at Credit Suisse, they demanded a $100 billion liquidity backstop – equal to 13% of Switzerland’s GDP – along with $9 billion in guarantees against future losses (or nearly 3x the price they paid to acquire Credit Suisse).

That’s the ticking time bomb that’s poised to detonate in the weeks and months ahead.

If it does, the threat to the U.S. banking system quickly moves from the $2 trillion in potential losses from unhedged positions to hitting an even bigger portion of the $23 trillion in total assets across the entire banking sector.

We’re All Banana Republics Now

Earlier this week, Bloomberg reported that U.S. authorities are currently studying “Ways to Insure All Bank Deposits If Crisis Grows.”

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is the agency in charge of insuring U.S. bank deposits, and paying depositors who lose money in the event of a bank failure. The FDIC collects deposit insurance premiums from the U.S. banking sector into a pool, which are set aside to pay out future claims.

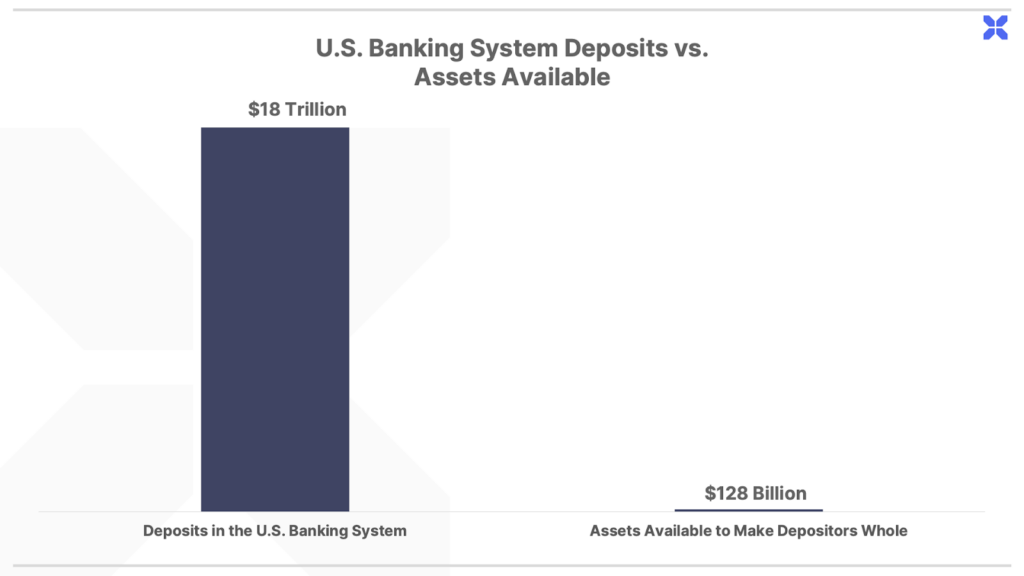

There’s just one small problem… the organization tasked with insuring the $18 trillion of deposits in the U.S. banking system has just $128 billion in assets available to make depositors whole.

The FDIC’s statutory authority permits it to borrow from the Treasury when it exhausts its funds.

And since the U.S. government, along with virtually every other Western government, is already borrowing money to fund runaway deficits, that means all roads lead back to the only remaining solution: more printed money.

In the very near term, the credit crunch rippling through the global financial sector will be very deflationary. And it will create once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to buy distressed assets at rock-bottom prices (as we discuss in our Distressed Investing service).

But this deflationary outbreak could prove very short-lived, as policymakers rush to bail out the system once again with newly issued currency. That’s why we believe investors should also start preparing for the next crisis.

And that next crisis could very well be the final crisis for America and other highly-indebted governments around the globe…

Eventually, the population will stop worrying about the viability of private banks, and start worrying about the viability of central banks and the currencies they issue. The coming loss of faith in government-issued currency will cause the ultimate bank run – a run on central banks.

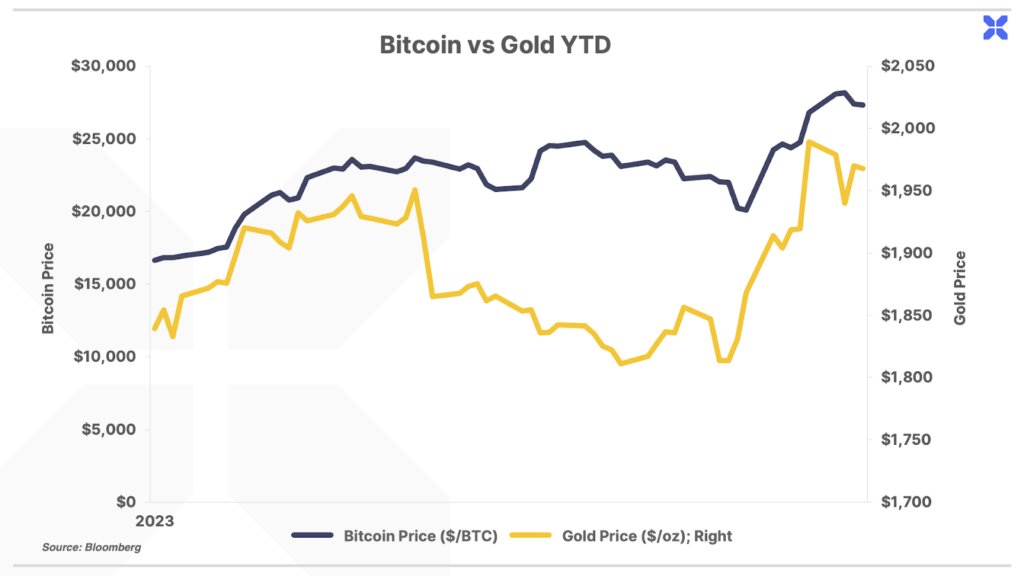

When that happens, the only escape valve will be hard money and tangible assets. Things that central banks can’t print, like copper and crude oil and natural gas. Things like Bitcoin and gold, the two ultimate stores of pure value.

In fact, it’s possible that this process is already underway, given the skyrocketing prices of Bitcoin and gold in the wake of the banking contagion over the past several weeks:

Next week, paid subscribers of The Big Secret on Wall Street will get access to a barbell investment strategy. The first part of this strategy will capitalize on the coming credit bust, with a unique investment vehicle managed by one of the best distressed investors on Wall Street. The second part provides a long-term hedge against the inflationary outbreak we see emerging from the other side.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team – all of whom are real humans, and many of whom have Twitter accounts – you can get acquainted with us here.