A record $2.5 trillion of CRE debt will mature between now and the end of 2027. However, several massive headwinds could make it more difficult than usual for borrowers to refinance these debts this time.

The Next Wave of Defaults Won’t Be In The Housing Market

Gordon Todd Skinner claimed that he had the world’s biggest Y2K food and weapons stockpile.

An intense, quiet former investment banker – so he said – Gordon showed up in the cornfield town of Wamego, Kansas in the mid-90s with a suitcase full of cash. He bought an abandoned missile silo – more on that below – and said he was hunkering down with enough canned goods and bullets to see through the collapse of the financial system, the internet and the power grid.

One evening, Gordon ducked out of his silo to visit the local strip joint, where he sweet-talked a girl named Krystle into going home with him. As Krystle later told Vice magazine, after a ride through the cornfields, Gordon drove up to “these huge metal gates with barbed wire along the top. He had at least ten security cameras outside, as well as these motion-sensing floodlights. There were no other buildings in sight, and the door to the missile silo was large enough to accommodate a semitruck.”

Inside the 16,000 sq foot bunker, there were no stockpiles of AR-15s or dehydrated veggies. Instead, Gordon’s silo bachelor pad featured imported jade and marble, and luxurious hot tubs.

And deeper underground, something more sinister…

Turned out, Gordon’s prepper story was just a cover. His missile silo housed an underground drug lab – where he made enough LSD to be the biggest producer in the United States.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration later estimated that during the second half of the 90s, Skinner and his partner, Leonard Pickard, produced as much as 90% of the total supply of the psychedelic drug circulating in the U.S. They cooked up to 20 million doses in their lab, with a street value of around $120 million, every month.

Skinner (the mastermind) and Pickard (the chemist) handled all that product from their Cold War-era silo: a massive, mostly underground labyrinth that had sat unused since the Air Force had decommissioned it in 1965. Skinner purchased the property with a $40,000 down payment, and immediately got to work making acid to pay his mortgage – and then some.

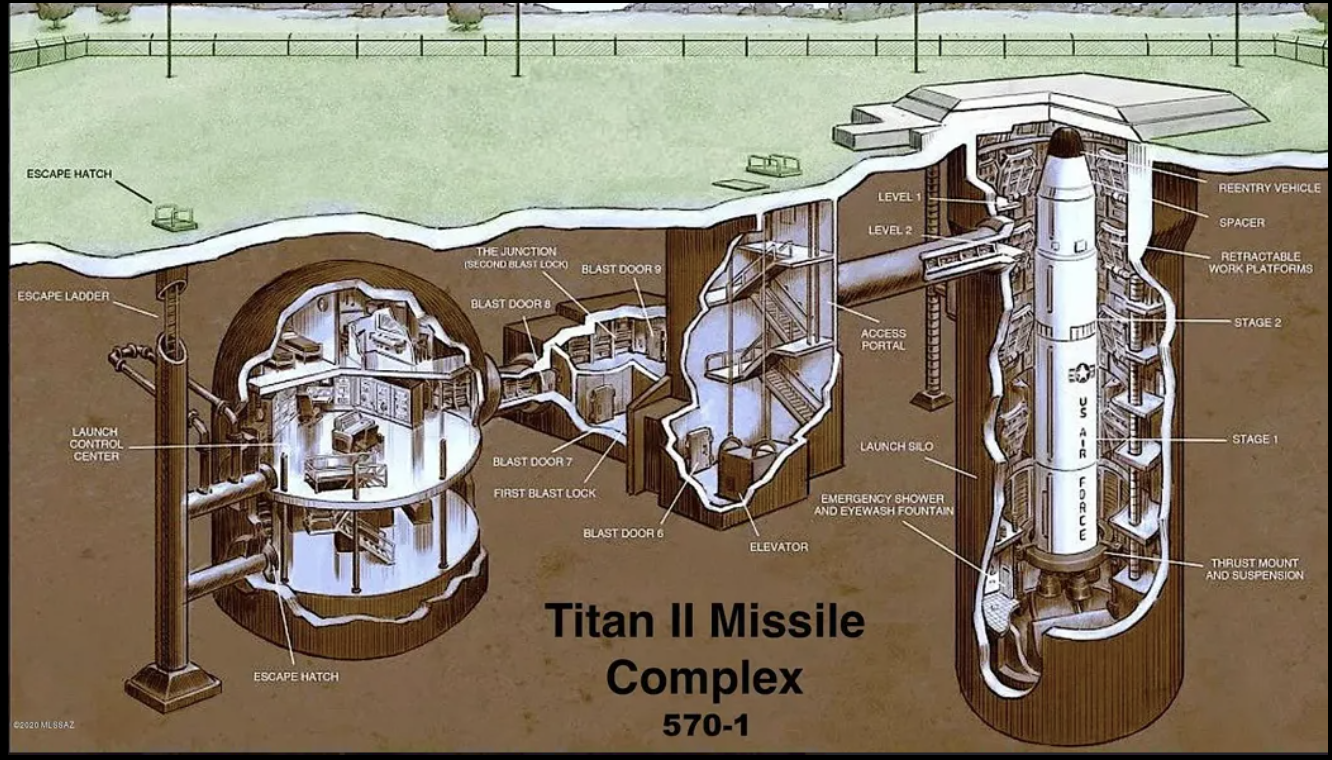

The Wamego site is just one of hundreds of abandoned Cold War nuclear sites across the U.S. The structures, which cost the government around $1 billion (that’s 1940s money) each to build, were designed to house “Nike” missiles, which would blow up Russian bomber planes as they flew overhead. It was a great strategy… as long as the enemy attacked via plane.

But in the 1950s, the Russians upped the ante in the arms race with intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), which could hit the enemy from thousands of miles away. That rendered ground-to-air defensive missiles like the Nikes obsolete. Over time, the U.S. government decommissioned and then removed the warheads.

The silos in the middle of nowhere that had housed them remained empty monuments to a bygone era.

Over the years, real estate adventurers have taken stabs at repurposing the sprawling structures. They’ve converted the underground caverns into mushroom farms, novelty hotels or obstacle courses. (There’s one for sale now near Topeka for $1.3 million if you’re interested.) More often, though, they’re big graffiti canvases.

Or, of course, drug dens. The Fed busted Skinner and Pickard in November 2000 and they both ended up with multiple life sentences, leaving Krystle – who’d dated Skinner for a while – single and with a great story for cocktail parties.

Today, the Wamego silo is owned by a perfectly normal couple, Charles and Kellie Everson, who live onsite and offer tours. The LSD is gone, but otherwise it’s a 1950s time capsule (with cheesy 1990s hot tubs added into the mix). After all, what are mainstream real estate developers going to do with a building that looks like this? (The diagram below shows the interior of a similar silo in southern Arizona.)

History is littered with ultra-specialized buildings left empty in the wake of progress.

Just look at Victorian-era industrial mills, abandoned as factories with smaller, more efficient equipment replaced their complex machinery… or at transatlantic cable stations, still standing on many beaches, but no longer needed due to wireless and satellite. Or Roman chariot racing stadiums. Or zeppelin hangars.

And today… look at office buildings.

Many of the structures that have anchored our downtowns for decades – those unusually shaped, impractical, sterile buildings, with too many windows for bedrooms, but not enough plumbing for bathrooms – are headed the way of the Cold War missile silos.

Here’s why… and what it means for investors.

A Real Estate Reckoning is Coming… But Not Where Most Folks Expect

Paid-up readers of The Big Secret on Wall Street know that we have a positive view on residential real estate in the U.S.

Due in part to the ongoing fallout from the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008-2009, the housing market suffers from a severe supply shortage that could last for the next decade or more. And this is likely to provide a powerful tailwind for homebuilders (especially capital efficient homebuilders) and other housing-related businesses, even while the overall economy faces a number of challenges.

Yet, while the housing market gets the most attention, it only accounts for around two-thirds of the estimated $65 trillion U.S. real estate market. The remainder (roughly $21 trillion) belongs to commercial real estate (CRE) – which includes office, industrial, retail, hotel, multi-family, and other commercial properties.

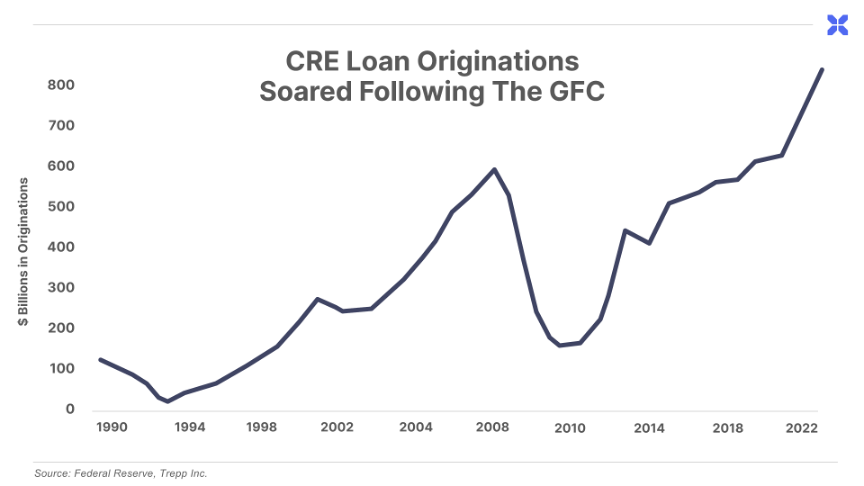

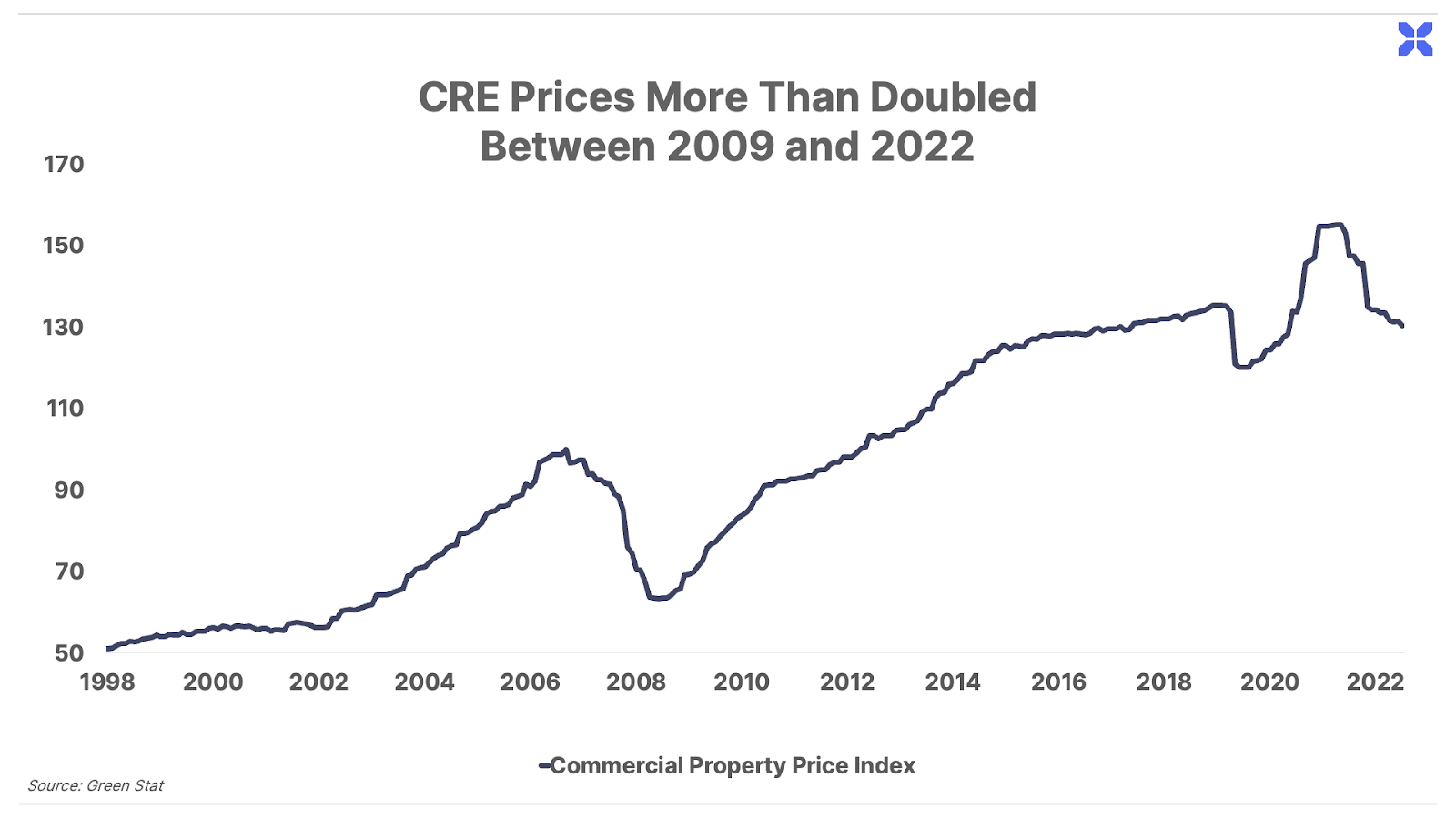

Unlike housing, the CRE market held up relatively well during the GFC. While prices did fall sharply, they recovered more quickly than home prices. CRE lenders in general also didn’t face the same existential threats as many mortgage lenders. So, as the Federal Reserve unleashed unprecedented monetary stimulus following that crisis, CRE was one of the biggest beneficiaries.

New CRE loans rose from less than $200 billion in 2010 to a record $862 billion in 2022. These loans totaled more than $6.6 trillion over this period – or more than 60% greater than the $4 trillion in total CRE borrowing in the 12 years that preceded the start of the GFC in 2008.

This massive wave of borrowing coincided with a huge increase in CRE prices.

According to real estate analytics firm Green Street Advisors, CRE prices more than doubled between 2009 and 2022, suggesting a substantial portion of these loans were issued based on elevated property values.

However, all bubbles eventually find a “pin,” and the Federal Reserve pricked this one when it began to raise interest rates early last year.

CRE prices peaked just as the Fed started to raise interest rates early last year:

Borrowing has been collapsing as well. New CRE loan volumes plunged 56% year-over-year in the first quarter of 2023, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. And further slowing is likely as a massive wave of existing loans comes due over the next few years.

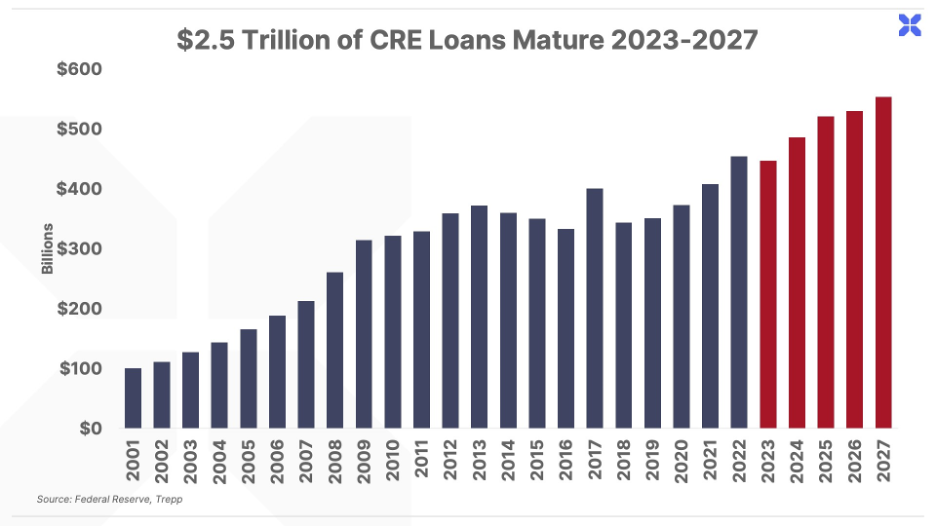

According to real estate data provider Trepp, a record $2.5 trillion of this debt will mature between now and the end of 2027, the most for any similar stretch on record.

However, unlike residential mortgages, nearly all CRE debt consists of “balloon loans.” These loans require borrowers to pay a significant lump sum – sometimes the entire principal borrowed – on the final maturity date.

Because real estate investments employ significant amounts of leverage, even the biggest investors typically don’t have the capital to pay off these sums in full at maturity. In some cases they may sell the property, but they’ll usually just refinance – essentially rolling over the remaining balance into a new loan.

The huge borrowing spree of the past decade-plus suggests CRE borrowers will need to refinance a record amount of debt over the next several years.

This would likely be challenging in any environment. However, several massive headwinds could make it more difficult than usual for CRE borrowers – and office CRE borrowers in particular – to refinance these debts this time.

A Perfect Storm for CRE

The first and most obvious headwind is higher interest rates, as mentioned earlier.

Since March 2022, the Fed has increased its short-term federal funds rate from 0.25% to 5.25% today. That is much higher than the 0% to 0.25% range that prevailed when borrowers took out these loans.

As a result, most borrowers will need to pay significantly higher rates to refinance these debts today.

For example, Trepp notes that 10-year deals signed in 2013 and 2014 paid an average rate of 4%. Those same loans are averaging close to 7% today.

This means that these borrowers’ monthly payments would rise by more than 60%, which could dramatically alter a property’s profitability and cash flow. (Think about how much less money you would have each month if your home mortgage payment went up 60%!)

And these borrowers face a second significant headwind: the availability of credit.

Banks are the single largest type of CRE lender, representing roughly 50% of the overall market. And the smallest banks (small, community, and regional) account for 70% of that share, according to FactSet.

Unfortunately, banks are dealing with significant problems of their own right now. Due to the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes, most banks are sitting on hundreds of billions of dollars of unrealized losses in “safe” Treasury bonds today.

Meanwhile, they’re also suffering from “deposit flight,” as customers have been increasingly moving their money out of banks and into higher-yielding instruments like money market funds and short-term Treasury bills.

This deadly combination was responsible for the failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank this spring. But many banks – particularly smaller ones – are facing identical risks and have pulled back on lending dramatically. Those who continue to lend are much more conservative than in recent years. This includes lending less and requiring that borrowers put up a larger percentage of their own capital.

As a result, borrowers needing to refinance aren’t just paying higher rates today; they’re also able to borrow less. And this trend may be just getting started, as credit conditions are likely to continue to tighten.

Despite the significant tightening in bank lending over the past few months, a recent study by Trepp found that as many as 30% of small and regional banks still have CRE loan exposure well above regulatory thresholds.

Given the recent bank crisis, regulators will eventually crack down on these issues. These banks will likely further reduce lending to allow existing CRE debt to “roll off” over time. In some cases, they could even be required to sell some of their existing loans as well.

These banking problems also make it more likely that “problem” borrowers will default on their mortgages…

In the aftermath of the GFC, banks realized that forcing widespread home foreclosures only amplified their losses. So rather than immediately taking losses on bad or non-performing mortgage loans, banks began granting extensions or otherwise modifying the terms of those loans instead.

This strategy – known as “extend and pretend,” because the lender “extends” or delays the repayment of the loan and “pretends” the borrower is current on payments – essentially bought banks time, in the hope that some of those loans might begin performing again before losses had to be realized. And it arguably helped to reduce losses and keep more people in their homes in that crisis.

However, many banks are already struggling with huge unrealized losses and deposit flight. So they’re unlikely to have the capital to make similar concessions with CRE loans today, making foreclosures (and losses) more likely.

The continued tightening of lending standards alone could push many of the weakest CRE borrowers (who don’t have the necessary additional capital to refinance) into default in the months ahead. According to a March report from JPMorgan Chase, at least 20% of existing office loans likely fall into this category.

And it gets worse. If CRE property values fall significantly, even relatively stronger borrowers could eventually default as they become increasingly “underwater” on loans that no longer make economic sense to refinance.

This is a possible risk for the broad CRE market, but it’s an especially serious one for office properties in particular.

COVID Popped the Office Bubble (Forever)

Soaring rates and tightening credit spell trouble for CRE. But office commercial real estate in particular faces gale-force headwinds – and an arguably existential threat – that the broad CRE market does not.

In March 2020, office occupancy (and occupancy rates in other types of CRE, like retail and hotels) plunged as COVID-19 lockdowns flash-froze the economy.

According to security-solution provider Kastle Systems, before the lockdowns, virtually everyone (98.9% of U.S. employees) was going into the office each workday. By April, that figure had plummeted to less than one out of every six (15.8%).

In many ways, the world has gradually returned to “business as usual” over the past year or so. We’re hugging and shaking hands, going to Olive Garden, wandering around the mall, and trying to forget about N-95 masks and coating everything in Lysol.

But the same can’t be said for how (and where) we work.

Video conferencing and other technologies made remote work possible for many employees for the first time. After several months of working from home, many folks realized they’d rather skip the commute and do so permanently. And many employers have also embraced this trend to cut costs.

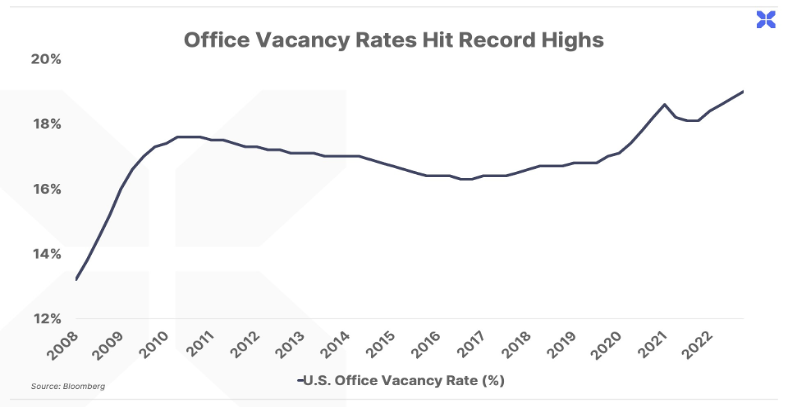

The net result is that, as of last month, only 50% of workers are back in the office on average today. And this has driven the nationwide office vacancy rate to an all-time high near 19%.

Vacancies are even higher in major cities like New York (23%), Chicago (22%), and San Francisco (30%).

According to real estate and investment management services firm Jones Lang LaSalle, the U.S. currently has 963 million square feet of empty office space. That’s the equivalent of nearly 17,000 football fields. If all of this space were stacked into a single office tower, it would be 48,000 stories high – enough to stretch 100 miles into the Earth’s atmosphere.

Post-Covid, the office space industry has insisted that it’s only a matter of time before Americans return to the office. Thinkpieces in the media tout the upside of returning to work, and claim that employees are happier and more productive in the cube, with headlines like “Why You May Actually Want to Go Back to the Office,” and “The Benefits of Returning to the Office for Businesses & Staff.”

But that’s looking less likely every day. (The editors of this piece are collaborating on a shared Google doc from several different locations – and it’s just as easy, if not more so, than comparing notes at a conference table.) Office work as we knew it has gone the way of the Nike defense missile… and, like the long-gone nuclear warheads, it’s left a trail of big, empty buildings in its wake.

The combination of soaring interest rates and much higher vacancies (and therefore much lower rents) suggests a significant percentage of office properties – particularly those of lower quality or in less desirable locations – are no longer economically viable in their current form.

In addition, because of structural differences in offices versus other types of real estate (such as centralized water and HVAC access), many of these properties can’t be converted for other uses without extensive (and cost-prohibitive) renovations.

As a result, even borrowers who can afford to refinance lower-tier office properties may choose to default rather than throw good money after bad. And like the Cold War missile silos scattered across America’s heartland, we suspect many of these buildings may ultimately be abandoned and left to decay.

A Slow-Motion Crisis is Now Underway

CRE transaction volumes have slowed dramatically over the past year, plunging 70% year-over-year through the first quarter of 2023, according to Green Street. Borrowers have been playing “wait and see” – hoping against hope that the Fed might slash interest rates or that property values might surge higher again before their debts come due.

Of course, that hasn’t happened. Instead, the Fed has continued to raise rates, and prices for all segments of the CRE market have continued to drift lower.

But the outlook is especially dire for office CRE.

Office property prices have led the broad CRE market lower – with the average sale price for an office building falling 22% year over year through May, according to CRE leasing and asset management software firm CommercialEdge.

And unlike most other types of CRE, even significantly lower interest rates are unlikely to make many vacant office buildings economical again. Again, that’s because they’re no longer useful in their current form, and can’t be repurposed without expensive renovations.

Office debt also makes up the single largest share (roughly 30%) of the nearly $400 billion in CRE debt maturing this year, according to Trepp. So it’s not surprising that we’re now beginning to see significant signs of stress in these loans over the past several months.

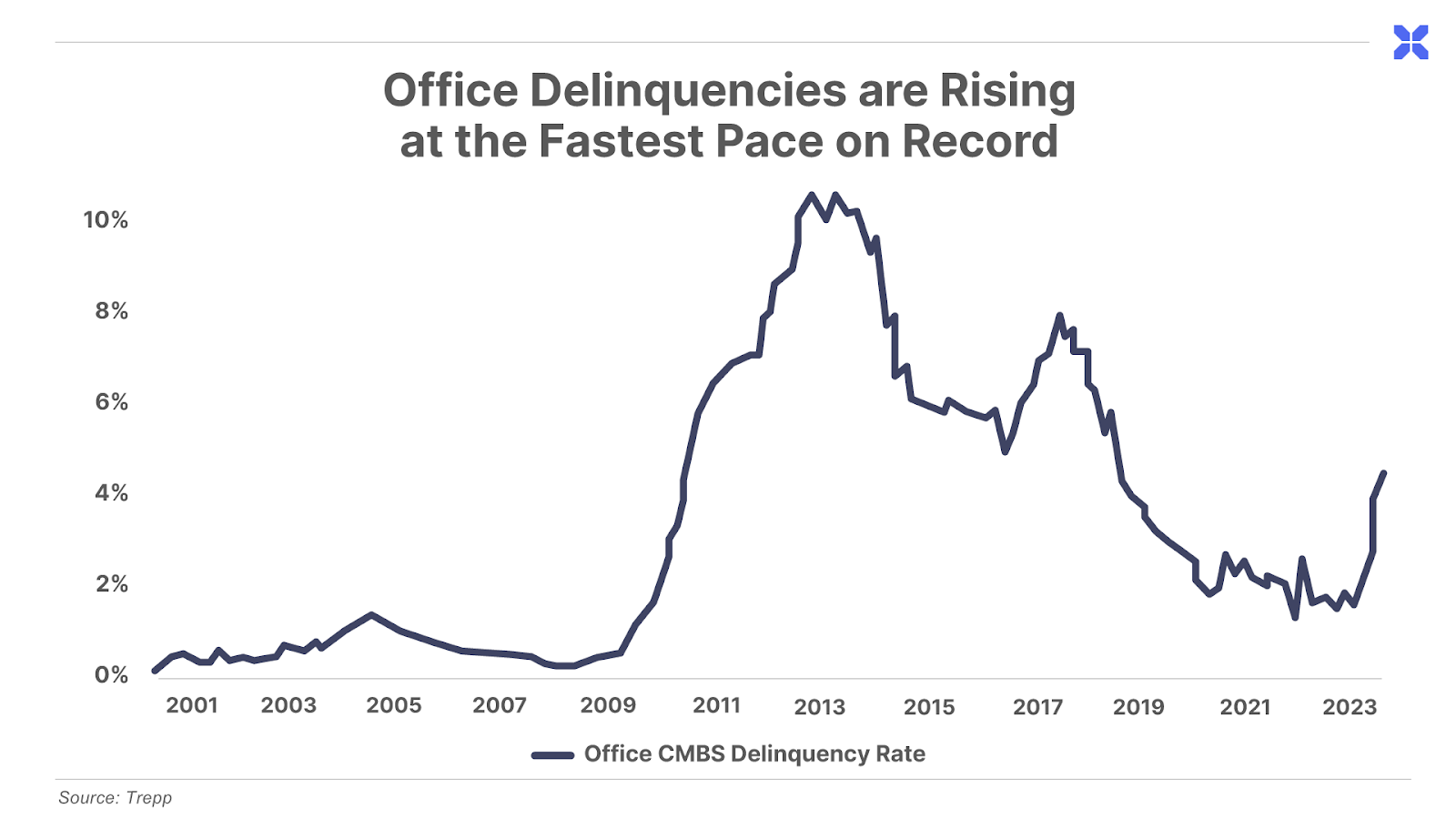

Delinquencies in the broad CRE market have gradually risen over the past year, from 3.2% to 3.9% through June.

But as shown below, office delinquencies have nearly tripled in just the past six months, rising to 4.5% from less than 1.6% at the end of 2022. That’s the sharpest six-month rise in this metric since Trepp began tracking it in 2000.

We’ve also seen some notable borrowers surrender in recent months.

In February, fixed-income manager PIMCO’s Columbia Property Trust defaulted on $1.7 billion in loans tied to seven office buildings in New York, San Francisco, Boston, and Jersey City. That same month investment giant Brookfield Asset Management defaulted on more than $750 million in debt on two office towers in Los Angeles.

In April, Brookfield defaulted on a $161 million loan tied to several office buildings in the Washington, D.C. area, while coworking company WeWork and private equity firm Rhone defaulted on a joint $240 million loan on an office tower in San Francisco.

Last month, real estate management firm RXR defaulted on a $240 million loan on an office tower in Manhattan.

And private equity giant Blackstone is currently in talks with lenders about refinancing a $350 million loan on a Chicago office tower due this month and could ultimately walk away.

These defaults represent the first drop of slow investment waterboarding: soaring defaults, falling prices, and, ultimately, massive losses for lenders and investors.

And importantly, these loans are going bad while the economy remains relatively healthy by most measures. A recession would only compound these problems.

We generally don’t recommend short positions here in The Big Secret. Most investors would do best to simply avoid investments with significant exposure to the office sector, including publicly-traded office real estate investment trusts (REITs) and many smaller banks. (You could also consider our most recent recommendation if you’re eager to invest in real estate today.)

However, in Porter & Co. Wealth Signals – our new macro-focused trading service – our colleague Scott Garliss recently highlighted a high-conviction short trade on one of the worst-positioned owners of office properties today.

This report is only available to Partner Pass subscribers. To learn more about becoming a Partner, call Lance, our customer concierge, toll-free at (888) 610-8895, or locally at (443) 815-4447.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team – all of whom are real humans, and many of whom have Twitter accounts – you can get acquainted with us here – or email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected].