The auto lending bubble is popping as more Americans are unable to pay their car loans. The tightening credit conditions that are weighing on subprime auto borrowers signal danger for the far larger corporate and government debt markets.

The U.S. Economy’s Car Payment Is Officially Past Due

The Subprime Auto Bubble Heralds A Much Bigger Crash

The Rosen Shingle Creek Hotel looks like any other upscale golf resort in Orlando, Florida.

You wouldn’t guess – from leafing through the Rosen’s fine-dining menu or strolling on its Arnold Palmer-engineered putting green – that back in April, it hosted a convention for “supervillains.”

The conference’s attendees weren’t Dr. Doom-level masterminds, of course. But they were a different brand of bad guys: the scary fellows who tow away your car after you’ve missed a payment or two.

They’re the repo men. (Cue the Iggy Pop theme from the 1984 hit film.) And they’re coming for your Nissan Altima… after they knock back a few cocktails at the swanky hotel bar, of course.

This year, the “Repossessors’ Summit” at the Rosen was bigger and glitzier than ever – featuring hands-on towing technique workshops in the hotel parking lot, pimped-out tow truck models like the self-loading $88K “Python,” and a cheesy Cinderella-themed tagline: “Putting the magic back in repossessions.” (After all, the Disney villain-esque event was held just a stone’s throw from the Magic Kingdom.)

Most of the several hundred conference attendees had dodged a bullet – that’s not a figure of speech – at least once during an otherwise regular workday. And about half of the business owners in the main exhibit hall were there in part to find new employees. “One of the main problems for the industry… is finding enough people to repossess all the cars,” Bloomberg reported from the scene. (In case the repo-man shortage persists, Ford has recently applied to patent a self-repossessing car that will drive itself to the nearest tow lot.)

As we predicted last summer, the auto lending bubble is popping. Many of the folks who bought fancy cars using their Covid stimulus checks have been unable to make their auto payments – resulting in an unwelcome visit from the repo man. The total number of repossessed cars was up 11% last year from 2021. And though the broad economy appears relatively healthy for now, by some metrics the auto lending market is already in worse shape than it was at the trough of the Great Financial Crisis in 2009.

That means big business (and more ritzy industry confabs) for the repo men. “As the economy curves down, our industry curves up,” said Ben Deese, a member of the American Recovery Association, the repo industry group that runs the conference in Orlando, as quoted by Bloomberg.

But the $1.7 billion car repossession business isn’t so magical for the folks who lose their wheels. Just ask Richard Sanchez, whose Toyota was repossessed in January after he failed to make the $750 monthly payments… or Sarah Fader, who’s crowdfunding back payments for the 19% interest rate loan on her Subaru.

With the average new car selling for close to $50,000 today, and the cost of used cars rising more than 50% over the past few years, it’s getting more and more difficult for many Americans to keep up on what is in much of the country a basic necessity.

Last year – in one of the very first issues of The Big Secret on Wall Street – we warned readers that the next financial crisis was already brewing… at your local used-car lot.

And that debt has now reached critical mass. The Repo Man is here.

The Next Subprime Bubble Is About To Go Bust

The last big wave of debt-fueled defaults (in 2008-2009) started in the mortgage market. This time, subprime auto loans are echoing that earlier bubble with aggressive loan creation, sloppy underwriting, and negligent income verification. (“Subprime” historically refers to higher-risk borrowers with credit scores of 600 or less, while “prime” borrowers have better scores, in the 600s or above.)

The auto sales boom started in the early 2010s, as the Federal Reserve and other central banks slashed interest rates to zero (or below) and unleashed massive monetary stimulus in response to the housing bust. These easy-money policies incentivized financial institutions to “reach for yield,” and made it simpler for people with less cash – and poorer credit – to buy cars.

Then COVID-19 tossed a match into the gas tank.

Pandemic-related shutdowns devastated supply chains for many industries, including carmakers. Meanwhile, the government’s massive stimulus payments were burning a hole in consumers’ pockets.

The combination of surging demand and a constrained supply of vehicles led to a huge increase in car prices.

The average price of a new car rose from around $36,000 before COVID-19 to a peak of $48,000 last year, an increase of more than 30%. The average used car rose more than 50% – from around $20,000 to more than $30,000 – over the same period.

Yet even after the “stimmies” began to dry up, consumers kept buying – turning to debt to finance expensive vehicles like never before.

And just like in the early-2000s housing boom, lenders pumped up the bubble by loosening credit standards aggressively – including issuing loans to progressively lower-quality borrowers, extending the duration of loans to an unheard-of 84 months (seven years!), and throwing standard income-verification safeguards out the window.

By last summer, the risks in this industry were as obvious as they were frightening:

- Subprime lending had reached a record $44 billion in 2021 – nearly 50% above the previous all-time high – and accounted for roughly 1/3 of all auto lending.

- The average consumer was borrowing $38,000 to finance new vehicle purchases.

- More than 70% of these loans were over 60 months (five years) in duration, and nearly 1/3 were over 72 months (6 years).

- More than 95% of borrowers were not subject to income verification.

- And up to 46% of existing loans were already “underwater” – with borrowers owing an average of $3,700 more than their vehicle was worth.

People with no money are buying millions of cars and not paying for them. This can’t go on for too much longer.

Though the credit markets – and the economy in general – have held up better than we would have anticipated last summer, we are now seeing the first indications that this overinflated tire has found a nail.

Worse than 2009… And the Real Crisis Hasn’t Even Started

Over the past year consumers have continued to borrow heavily to buy cars.. The total amount of outstanding auto debt rose to a record $1.56 trillion in the first quarter of 2023, up from around $1.4 trillion last summer.

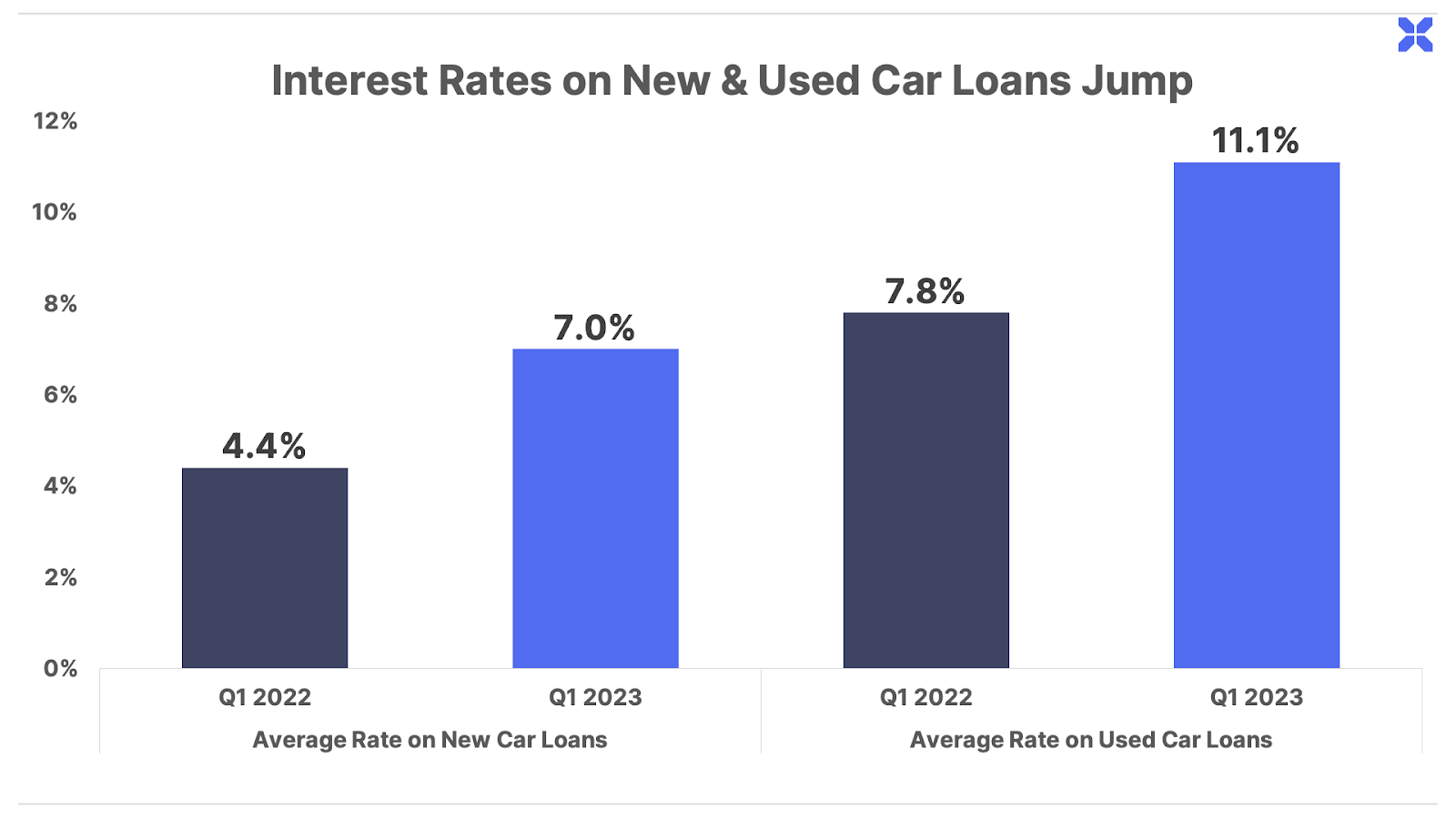

And the interest rates on that debt have reached Alpine heights.

According to automotive appraiser Edmunds, the average interest rate on new and used car loans rose from 4.4% and 7.8%, respectively, in the first quarter of 2022 to 7.0% and 11.1% this year.

Credit reporting firm Experian notes subprime borrowers are paying even more, with average rates as high as 14% and 21%, respectively, today.

The combination of rising interest rates and surging auto prices means payments have soared. According to Bloomberg, the average monthly payment for new vehicles rose to an all-time high of nearly $800 in the first quarter, or nearly double the average monthly payment over the previous decade. A record 17% of borrowers – or more than one out of every six – are now paying $1,000 or more each month, compared to just 6.2% in 2021 according to Edmunds.

Moreover, borrowers are increasingly “underwater” on their loans (owing more on their car than the car is actually worth) Edmunds data shows the average “negative equity value” on trade-ins – that is, how much the average borrower was actually underwater on their loan – was more than $5,300 at the end of last year, up roughly 30% from the prior year.

The Sick Wolves Fall Behind

Given these startling trends, it’s little surprise that a significant number of the weakest borrowers are falling behind on their loans. The ailing members of the pack always drop out first.

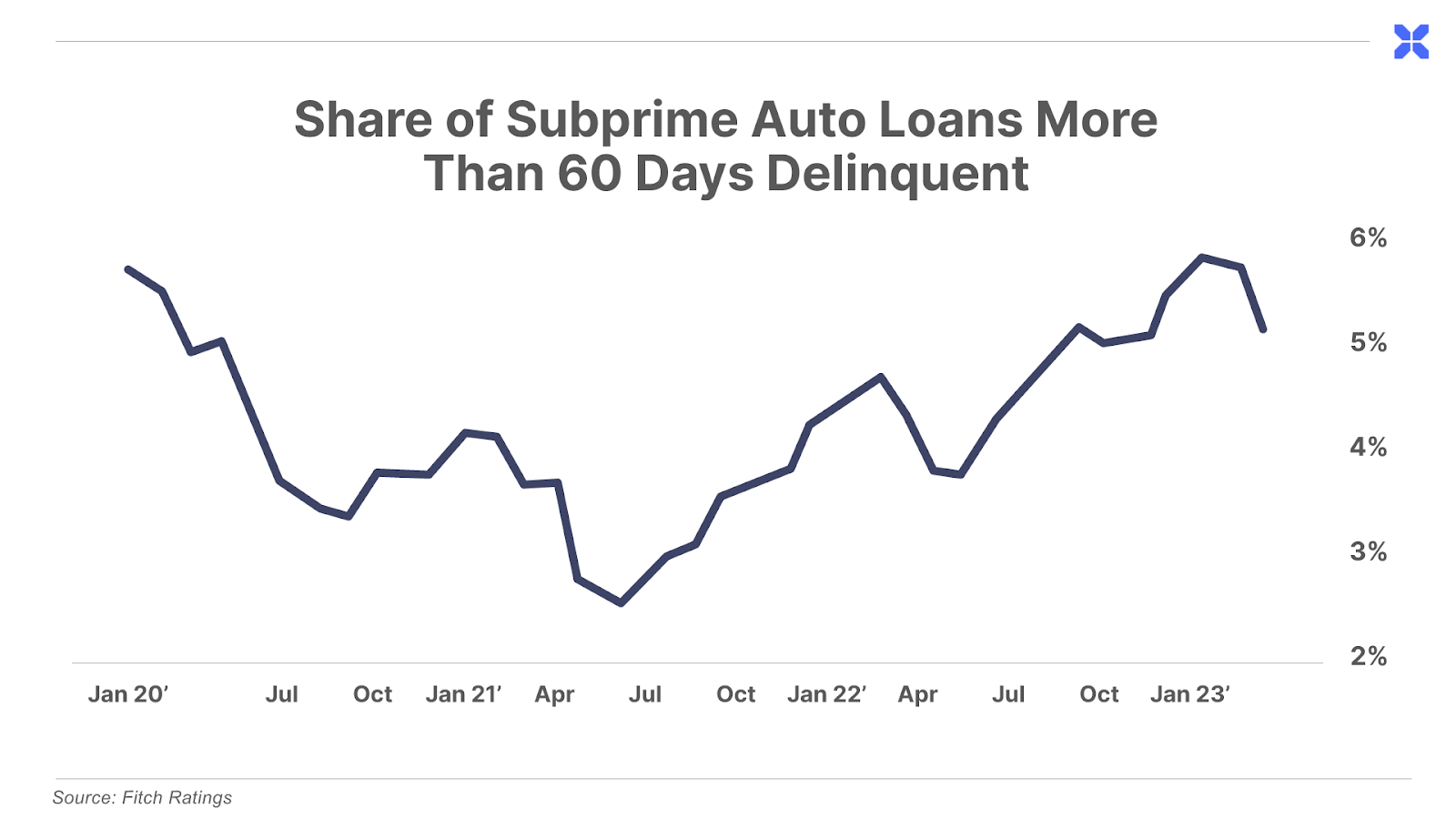

According to Fitch Ratings, the percentage of subprime auto borrowers who are more than 60 days late on their payments rose to 5.93% in January. That may not sound particularly worrisome, but it’s actually higher than the peak of the Great Financial Crisis in 2009.

You’ll notice in the graph above that delinquencies fell over the past few months. This isn’t unusual, as borrowers often use tax refunds – issued by the IRS in the spring – to pay bills. However, last month’s delinquency rate of 4.7% is still the highest level for any May on record, dating back to the early 1990s.

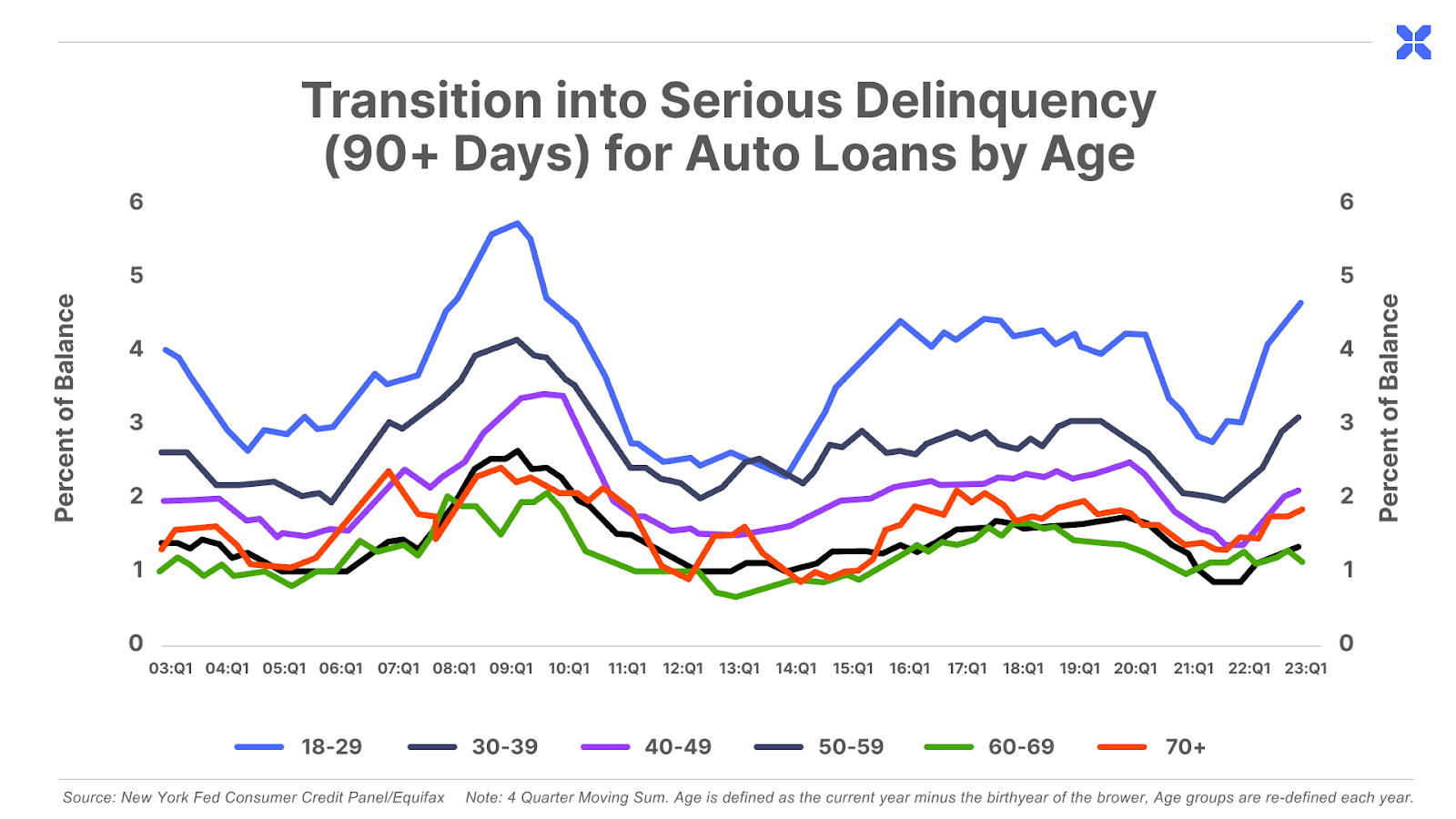

Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggest that younger borrowers, in particular, are under pressure.

Its latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit shows nearly 4.6% of borrowers under 30 years old are now in “serious delinquency” on their auto loans – meaning they’ve missed at least 90 days of payments. This figure is also challenging its Great Financial Crisis peak.

Importantly, the Fed’s data includes borrowers across the credit spectrum, not just those in the subprime segment. This suggests even younger borrowers with relatively higher credit scores are beginning to struggle.

This is especially concerning, given that tens of millions of (mostly younger) Americans will soon have to resume monthly student loan repayments, as the post-COVID forbearance program is set to end this summer.

In the meantime, rising delinquencies are already causing significant losses in the auto industry. And over the past several months, we’ve seen a handful of notable lenders and dealers pulling back from or exiting the market altogether:

- In January, Citizens Bank announced plans to cut its auto loan portfolio by nearly 60% over the next year.

- Mechanics Bank announced it was closing its entire auto lending business in February.

- In early April, Capital One – one of the largest auto lenders in the U.S. – announced it would no longer extend “floor plan” credit to dealerships as a result of rising losses.

- Soon after, Wells Fargo laid off all of its junior auto loan underwriters and announced it was significantly tightening lending standards.

- U.S. Auto Sales – one of the country’s biggest subprime used car dealers – announced it was indefinitely closing all 39 of its dealerships in April.

- And just this month, Citizens Bank updated its previous plans and announced it intended to exit the auto lending business entirely.

These are likely just the first of many lenders to back out of the auto loan biz. Yet this nascent trend is already having a significant impact on credit conditions.

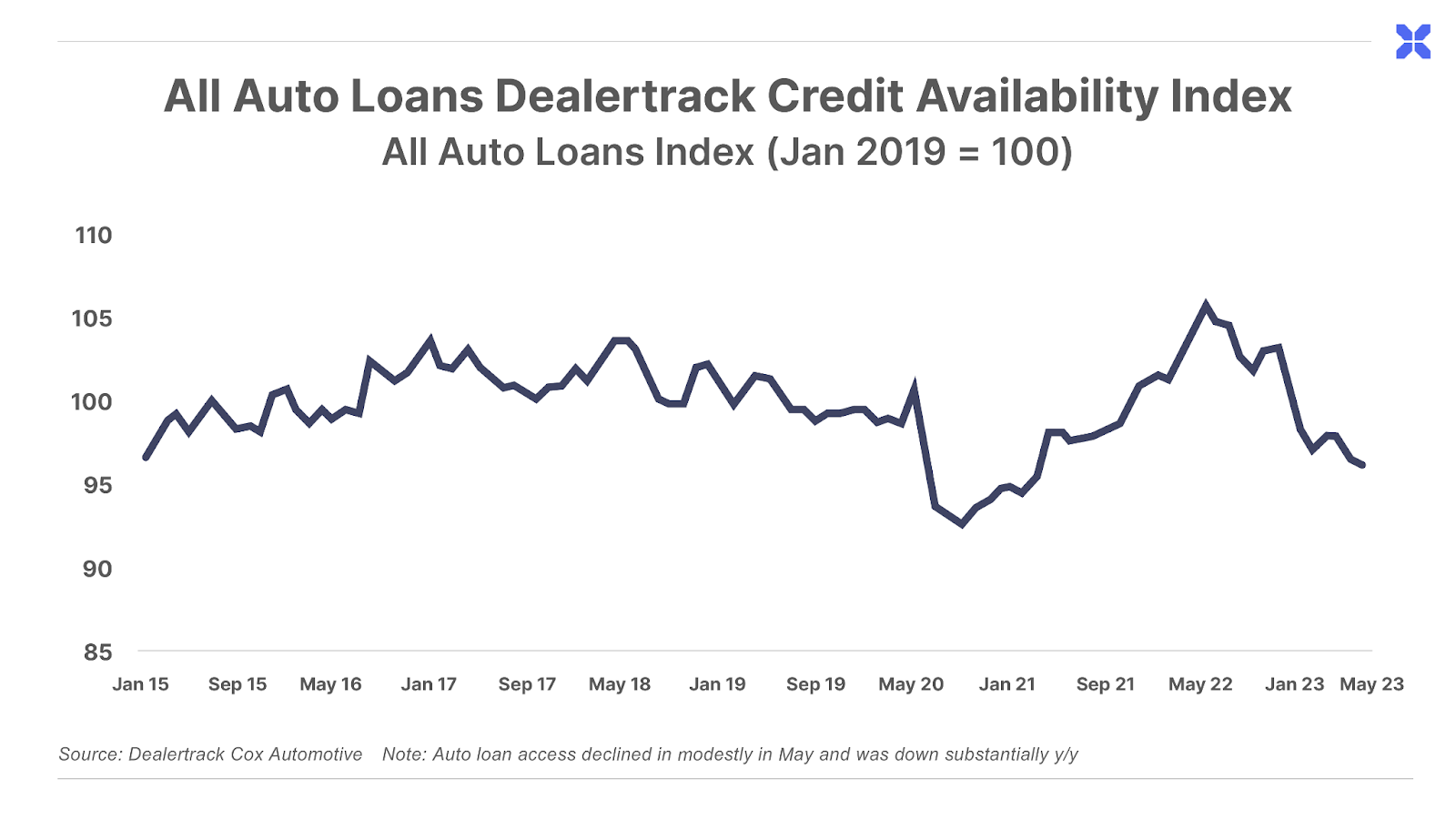

As the chart below shows, credit availability has been tightening significantly for the past year, and has fallen to levels last seen near the worst of the COVID crisis.

This index tracks shifts in loan approval rates, subprime share, yield spreads, and loan details – including term length, negative equity, and down payments – to represent the relative ease or difficulty in obtaining an auto loan.

More alarming, the recent rise in subprime auto delinquencies points to a bigger systemic problem…

The Economy’s “Check Engine Light” is Flashing

Due to its relatively heavy exposure to subprime borrowers, the auto lending industry can also serve as an early warning signal for the broad economy.

Higher risk, less-creditworthy borrowers tend to be highly sensitive to changes in credit conditions. Like the clichéd canaries that coal miners carried underground to chirp at the first whiff of toxic gas, subprime borrowers often experience trouble before it shows up elsewhere in the economy.

We saw this ahead of the last crisis in the late 2000s. Only that time, it was subprime mortgages – rather than subprime auto loans – that started “dropping dead” nearly a year before the crisis was headline news.

To be clear, we don’t expect the coming auto crisis to be a repeat of the 2008 housing bust. That’s partly because the auto loan market is a tiny fraction of the size of the mortgage market that triggered the crisis back then. But that doesn’t mean it can’t cause significant fallout in markets and the economy.

And more importantly, the same tightening credit conditions that are beginning to weigh on subprime auto borrowers could ultimately work their way into the much larger corporate and government debt markets, where similar excesses could trigger more significant breakdowns.

Ever since last summer, when we began reporting on the global debt bubble at Porter & Co., we’ve been recommending capital efficient, protective investments (what we like to call “battleship stocks”).

Including one that might be a little surprising to newer readers…

The One Subprime Lender That Will Beat The Auto Bust

To return briefly to Florida – conference destination for the repo men, and “hurricane central” for many other folks – we’ll find protection from the auto bubble in the very eye of the storm.

That’s right – we’re currently recommending shares of a subprime auto lender to our paid Big Secret readers. In fact, it’s one of our top three “best buys” in our Big Secret portfolio today.

That’s because this company – which we’ve jokingly dubbed “the Goldman Sachs of White Trash” – is no ordinary lender. Its unique business model and risk management process is built to survive – and thrive – in even the most difficult markets.

Unlike traditional auto lenders, it prices loans with an exceptionally high margin of safety. It also transfers a substantial portion of the remaining risk to the auto dealer it partners with to make each loan. This has allowed it to consistently grow profits each and every year for the past two decades – including during the 2007-2009 crisis, when most other lenders suffered massive losses or were wiped out completely.

This “antifragile” strategy allows it to benefit from crises – to dramatically grow market share as other lenders pull back and come out even stronger on the other side.

Shares have recently sold off this year along with those of most other auto lenders, as investors have become concerned about the rising delinquencies and loan losses we mentioned earlier. But we believe that’s missing the forest for the trees.

While most are focused on these short-term headwinds, this company is already beginning to take market share as major competitors retreat. And we expect this trend to accelerate as the crisis unfolds.

In other words, this company’s unique competitive strength is playing out exactly as we expected. And it makes sense to look past these headwinds to be positioned for its massive long-term potential.

We shared a detailed update on this recommendation in the May 12 edition of The Big Secret on Wall Street.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team – all of whom are real humans, and many of whom have Twitter accounts – you can get acquainted with us here – or email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected].