The Quiet Man Who Mentored Many Great Investors

The Benjamin Graham of Growth-Stock Investing

Editor’s Note: Porter & Co. is following a lighter publishing schedule this month. We continue to monitor all of our portfolios – and we are sending to paid subscribers a Big Secret on Wall Street portfolio update in a separate email today. We will also send buy and sell alerts on our open positions when needed for all services.

For the month of August, we’re producing a special series called “What We’re Reading.” Each Friday, we are sending Big Secret readers a literary excerpt or investing insight that you won’t see anywhere else.

Members of the Porter & Co. team are sharing an excerpt from their personal summer reading – books that they found instructive, or ones that they just plain enjoyed. We hope you’ll enjoy them too.

Last week, publisher and CEO Kim Iskyan provided an excerpt of The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics, by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith. In his introduction, Kim also shared his insights into this work about leadership and power in business and politics.

This week, Big Secret on Wall Street analyst Ross Hendricks is providing for readers an excerpt of Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings, an investing classic by Philip A. Fisher… whose work directly inspired Warren Buffett’s investment strategy.

Ross leads off the book selection with a brief introduction about Fisher’s legacy.

Warren Buffett once described his investment philosophy as “85% Benjamin Graham and 15% Phil Fisher.”

Graham is the better-known among the two, often called the “Father of Value Investing.” As both a college professor and mentor to Warren Buffett, Graham played a major role in shaping Buffett’s early investing style. His approach advocated a “margin of safety” above all else, which meant only buying stocks that traded at a discount to their liquidation value. Known as “cigar butt” investing, the companies were so cheap that they offered the equivalent of a free puff from a cigar butt found lying on the street.

Philip Fisher may well be considered the Benjamin Graham of growth-stock investing. An investor and money manager who dropped out of Stanford Business School to work as a securities analyst in 1928, he gave few interviews during his 71-year career and was a notably reticent and private person.

Instead of talking, Fisher wrote. He was among the first authors to develop and publish a cogent and comprehensive framework for identifying stocks capable of compounding shareholder wealth over many decades.

Buffett famously avoided these stocks during his early days, because these high-quality businesses often traded at seemingly high valuations.

But Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner, the late Charlie Munger, was a disciple of Fisher’s approach. And he realized that paying up for high-quality stocks was ultimately the easiest and surest path toward long-term wealth creation. In classic Munger style, he distilled this philosophy into a simple maxim:

“It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

In the late 1950s, Munger was instrumental in helping Buffett see the value in paying up for high-quality stocks, by preaching the “Fisher doctrine,” as Buffett recalls:

“I met Charlie in 1959, and Charlie was sort of preaching the Fisher doctrine to me… It made a lot of sense to me. Fisher’s basic investment style was to invest in a small number of companies with tremendous outlooks and do nothing.”

This sparked a critical shift in Buffett’s stock-picking approach away from asset-heavy companies, whose value could be easily calculated, but where the returns were limited to a single puff of the discarded cigar. Over the next several years, Buffett perfected his new investment strategy and learned to embrace world-class companies with intangible assets, like American Express, Coca-Cola… and, more recently, Apple.

These are the businesses that built Buffett’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, into the world’s greatest engine of wealth creation. And these are the kinds of “forever stocks” we focus on at The Big Secret on Wall Street. Philip Fisher laid out a comprehensive investing framework for how to identify these kinds of companies in Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits. While the book was first published nearly 70 years ago, its timeless principles ring just as true today as they did in 1957. We highly recommend reading the entire work. But for starters, we’ve selected an excerpt, from Chapter 3, that we believe contains the best summary of Fisher’s framework for finding forever stocks. – Ross Hendricks

Chapter 3: The 15 Points to Look for in a Common Stock

What are these matters about which the investor should learn if he is to obtain the type of investment which in a few years might show him a gain of several hundred percent, or over a longer period of time might show a correspondingly greater increase? In other words, what attributes should a company have to give it the greatest likelihood of attaining this kind of results for its shareholders?

There are 15 points with which I believe the investor should concern himself. A company could well be an investment bonanza if it failed fully to qualify on a very few of them. I do not think it could come up to my definition of a worthwhile investment if it failed to qualify on many. Some of these points are matters of company policy; others deal with how efficiently this policy is carried out. Some of these points concern matters which should largely be determined from information obtained from sources outside the company being studied, while others are best solved by direct inquiry from company personnel. These fifteen points are:

POINT 1. Does the company have products or services with sufficient market potential to make possible a sizable increase in sales for at least several years?

It is by no means impossible to make a fair one-time profit from companies with a stationary or even a declining sales curve. Operating economies resulting from better control of costs can at times create enough improvement in net income to produce an increase in the market price of a company’s shares. This sort of one-time profit is eagerly sought by many speculators and bargain hunters. It does not offer the degree of opportunity, however, that should interest those desiring to make the greatest possible gains from their investment funds.

Neither does another type of situation which sometimes offers a considerably larger degree of profit. Such a situation occurs when a changed condition opens up a large increase in sales for a period of a very few years, after which sales stop growing. A large-scale example of this is what happened to the many radio set manufacturers with the commercial development of television. A huge increase in sales occurred for several years. Now that nearly 90% of United States homes that are wired for electricity have television sets, the sales curve is again static. In the case of a great many companies in the industry, a large profit was made by those who bought early enough. Then as the sales curve leveled out, so did the attractiveness of many of these stocks.

Not even the most outstanding growth companies need necessarily be expected to show sales for every single year larger than those of the year before. In another chapter I will attempt to show why the normal intricacies of commercial research and the problems of marketing new products tend to cause such sales increases to come in an irregular series of uneven spurts rather than in a smooth year-by-year progression. The vagaries of the business cycle will also have a major influence on year-to-year comparisons. Therefore growth should not be judged on an annual basis but, say, by taking units of several years each. Certain companies give promise of greater than normal growth not only for the next several-year period, but also for a considerable time beyond that.

Those companies which decade by decade have consistently shown spectacular growth might be divided into two groups. For lack of better terms I will call one group those that happen to be both “fortunate and able” and the other group those that are “fortunate because they are able.” A high order of management ability is a must for both groups. No company grows for a long period of years just because it is lucky. It must have and continue to keep a high order of business skill, otherwise it will not be able to capitalize on its good fortune and to defend its competitive position from the inroads of others.

The Aluminum Company of America is an example of the “fortunate and able” group. The founders of this company were men with great vision. They correctly foresaw important commercial uses for their new product. However, neither they nor anyone else at that time could foresee anything like the full size of the market for aluminum products that was to develop over the next seventy years. A combination of technical developments and economies, of which the company was far more the beneficiary than the instigator, was to bring this about. Alcoa has and continues to show a high order of skill in encouraging and taking advantage of these trends. However, if background conditions, such as the perfecting of airborne transportation, had not caused influences completely beyond Alcoa’s control to open up extensive new markets, the company would still have grown – but at a slower rate.

The Aluminum Company was fortunate in finding itself in an even better industry than the attractive one envisioned by its early management. The fortunes made by many of the early stockholders of this company who held onto their shares is of course known to everyone. What may not be so generally recognized is how well even relative newcomers to the stockholder list have done. When I wrote the original edition, Alcoa shares were down almost 40% from the all-time high made in 1956. Yet at this “low” price the stock showed an increase in value of almost 500% over not the low price, but the median average price at which it could have been purchased in 1947, just ten years before.

Now let us take Du Pont as an example of the other group of growth stocks – those which I have described as “fortunate because they are able.” This company was not originally in the business of making nylon, cellophane, lucite, neoprene, orlon, milar, or any of the many other glamorous products with which it is frequently associated in the public mind and which have proven so spectacularly profitable to the investor.

For many years Du Pont made blasting powder. In time of peace its growth would largely have paralleled that of the mining industry. In recent years, it might have grown a little more rapidly than this as additional sales volume accompanied increased activity in road building. None of this would have been more than an insignificant fraction of the volume of business that has developed, however, as the company’s brilliant business and financial judgment teamed up with superb technical skill to attain a sales volume that is now exceeding two billion dollars each year. Applying the skills and knowledge learned in its original powder business, the company has successfully launched product after product to make one of the great success stories of American industry. The investment novice taking his first look at the chemical industry might think it is a fortunate coincidence that the companies which usually have the highest investment rating on many other aspects of their business are also the ones producing so many of the industry’s most attractive growth products. Such an investor is confusing cause and effect to about the same degree as the unsophisticated young lady who returned from her first trip to Europe and told her friends what a nice coincidence it was that wide rivers often happened to flow right through the heart of so many of the large cities. Studies of the history of corporations such as Du Pont or Dow or Union Carbide show how clearly this type of company falls into the “fortunate because they are able” group so far as their sales curve is concerned.

Possibly one of the most striking examples of these “fortunate because they are able” companies is General American Transportation. A little over 50 years ago when the company was formed, the railroad equipment industry appeared a good one with ample growth prospects. In recent years few industries would appear to offer less rewarding prospects for continued growth. Yet when the altered outlook for the railroads began to make the prospects for the freight car builders increasingly less appealing, brilliant ingenuity and resourcefulness kept this company’s income on a steady uptrend. Not satisfied with this, the management started taking advantage of some of the skills and knowledge learned in its basic business to go into other unrelated lines affording still further growth possibilities.

A company which appears to have sharply increasing sales for some years ahead may prove to be a bonanza for the investor regardless of whether such a company more closely resembles the “fortunate and able” or the “fortunate because it is able” type. Nevertheless, examples such as General American Transportation make one thing clear. In either case the investor must be alert as to whether the management is and continues to be of the highest order of ability; without this, the sales growth will not continue.

Correctly judging the long-range sales curve of a company is of extreme importance to the investor. Superficial judgment can lead to wrong conclusions. For example, I have already mentioned radio-television stocks as an instance where instead of continued long-range growth there was one major spurt as the homes of the nation acquired television sets.

Nevertheless, in recent years certain of these radio-television companies have shown a new trend. They have used their electronic skills to build up sizable businesses in other electronic fields such as communication and automation equipment. These industrial and, in some cases, military electronic lines give promise of steady growth for many years to come. In a few of these companies, such as Motorola for example, they already are of more importance than the television operation. Meanwhile, certain new technical developments afford a possibility that in the early 1960s current model television sets will appear as awkward and obsolete as the original wall-type crank-operated hand telephones appear today.

One potential development, color television, has possibly been over-discounted by the general public. Another is a direct result of transistor development and printed circuitry. It is a screen-type television with sets that would be little different in size and shape from the larger pictures we now have on our walls. The present bulky cabinet would be a thing of the past. Should such developments obtain mass commercial acceptance, a few of the technically most skillful of existing television companies might enjoy another major spurt in sales even larger and longer lasting than that which they experienced a few years ago. Such companies would find this spurt superimposed on a steadily growing industrial and military electronics business. They would then be enjoying the type of major sales growth which should be the first point to be considered by those desiring the most profitable type of investments.

I have mentioned this example not as something which is sure to happen, but rather as something which could easily happen. I do so because I believe that in regard to a company’s future sales curve there is one point that should always be kept in mind. If a company’s management is outstanding and the industry is one subject to technological change and development research, the shrewd investor should stay alert to the possibility that management might handle company affairs so as to produce in the future exactly the type of sales curve that is the first step to consider in choosing an outstanding investment.

Since I wrote these words in the original edition, it might be interesting to note, not what “is sure to happen” or “may happen,” but what has happened in regard to Motorola. We are not yet in the early 1960s, the closest time to which I refer as affording a possibility of developing television models that will obsolete those of the 1950s. This has not happened nor is it likely to do so in the near future. But in the meanwhile, let us see what an alert management has done to take advantage of technological change to develop the type of upward sales curve that I stated was the first requisite of an outstanding investment.

Motorola has made itself an outstanding leader in the field of two-way electronic communications that started out as a specialty for police cars and taxicabs, and now appears to offer almost unlimited growth. Trucking companies, owners of delivery fleets of all types, public utilities, large construction projects, and pipe lines are but a few of the users of this type of versatile equipment. Meanwhile, after several years of costly developmental effort, the company has established a semiconductor (transistor) division on a profitable basis which appears headed toward obtaining its share of the fabulous growth trend of that industry. It has become a major factor in the new field of stereophonic phonographs and is obtaining an important and growing new source of sales in this way. By a rather unique style tie-up with a leading national furniture manufacturer (Drexel), it has significantly increased its volume in the higher-priced end of its television line. Finally, through a small acquisition it is just getting into the hearing-aid field and may develop other new specialties as well. In short, while some time in the next decade important major stimulants may cause another large spurt in its original radio-television lines, this has not happened yet nor is it likely to happen soon. Yet management has taken advantage of the resources and skills within the organization again to put this company in line for growth. Is the stock market responding to this? When I finished writing the original edition, Motorola was 45½. Today it is 122.

When the investor is alert to this type of opportunity, how profitable may it be? Let us take an actual example from the industry we have just been discussing. In 1947 a friend of mine in Wall Street was making a survey of the infant television industry. He studied approximately a dozen of the principal set producers over the better part of a year. His conclusion was that the business was going to be competitive, that there were going to be major shifts in position between the leading concerns, and that certain stocks in the industry had speculative appeal. However, in the process of this survey it developed that one of the great shortages was the glass bulb for the picture tube.The most successful producer appeared to be Corning Glass Works. After further examination of the technical and research aspects of Corning Glass Works it became apparent that this company was unusually well qualified to produce these glass bulbs for the television industry. Estimates of the possible market indicated that this would be a major source of new business for the company. Since prospects for other product lines seemed generally favorable, this analyst recommended the stock for both individual and institutional investment. The stock at that time was selling at about 20. It has since been split 2½-for-1 and 10 years after his purchase it was selling at over 100, which was the equivalent of a price of 250 on the old stock.

POINT 2. Does the management have a determination to continue to develop products or processes that will still further increase total sales potentials when the growth potentials of currently attractive product lines have largely been exploited?

Companies which have a significant growth prospect for the next few years because of new demand for existing lines, but which have neither policies nor plans to provide for further developments beyond this may provide a vehicle for a nice one-time profit. They are not apt to provide the means for the consistent gains over ten or 25 years that are the surest route to financial success. It is at this point that scientific research and development engineering begin to enter the picture. It is largely through these means that companies improve old products and develop new ones. This is the usual route by which a management not content with one isolated spurt of growth sees that growth occurs in a series of more or less continuous spurts.

The investor usually obtains the best result in companies whose engineering or research is to a considerable extent devoted to products having some business relationship to those already within the scope of company activities. This does not mean that a desirable company may not have a number of divisions, some of which have product lines quite different from others. It does mean that a company with research centered around each of these divisions, like a cluster of trees each growing additional branches from its own trunk, will usually do much better than a company working on a number of unrelated new products which, if successful, will land it in several new industries unrelated to its existing business.

At first glance Point 2 may appear to be a mere repetition of Point 1. This is not the case. Point 1 is a matter of fact, appraising the degree of potential sales growth that now exists for a company’s product. Point 2 is a matter of management attitude. Does the company now recognize that in time it will almost certainly have grown up to the potential of its present market and that to continue to grow it may have to develop further new markets at some future time? It is the company that has both a good rating on the first point and an ‘affirmative attitude on the second that is likely to be of the greatest investment interest.

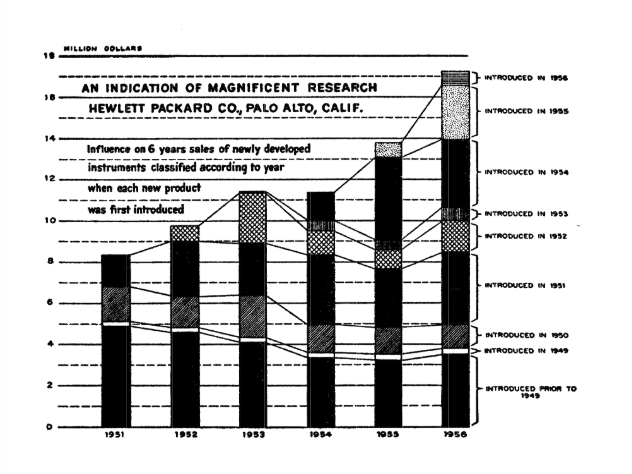

POINT 3. How effective are the company’s research and development efforts in relation to its size?

For a large number of publicly-owned companies it is not too difficult to get a figure showing the number of dollars being spent each year on research and development. Since virtually all such companies report their annual sales total, it is only a matter of the simplest mathematics to divide the research figure by total sales and so learn the percent of each sales dollar that a company is devoting to this type of activity. Many professional investment analysts like to compare this research figure for one company with that of others in the same general field. Sometimes they compare it with the average of the industry, by averaging the figures of many somewhat similar companies. From this, conclusions are drawn both as to the importance of a company’s research effort in relation to competition and the amount of research per share of stock that the investor is getting in a particular company.

Figures of this sort can prove a crude yardstick that may give a worthwhile hint that one company is doing an abnormal amount of research or another not nearly enough. But unless a great deal of further knowledge is obtained, such figures can be misleading. One reason for this is that companies vary enormously in what they include or exclude as research and development expenses. One company will include a type of engineering expense that most authorities would not consider genuine research at all, since it is really tailoring an existing product to a particular order-in other words, sales engineering. Conversely, another company will charge the expense of operating a pilot plant on a completely new product to production rather than research. Most experts would call this a pure research function, since it is directly related to obtaining the know-how to make a new product. If all companies were to report research on a comparable accounting basis, the relative figures on the amount of research done by various well-known companies might look quite different from those frequently used in financial circles.

In no other major subdivision of business activity are to be found such great variations from one company to another between what goes in as expense and what comes out in benefits as occurs in research. Even among the best-managed companies this variation seems to run in a ratio of as much as two to one. By this is meant some well-run companies will get as much as twice the ultimate gain for each research dollar spent as will others. If averagely-run companies are included, this variation between the best and the mediocre is still greater. This is largely because the big strides in the way of new products and processes are no longer the work of a single genius. They come from teams of highly trained men, each with a different specialty. One may be a chemist, another a solid state physicist, a third a metallurgist and a fourth a mathematician. The degree of skill of each of these experts is only part of what is needed to produce outstanding results. It is also necessary to have leaders who can coordinate the work of people of such diverse backgrounds and keep them driving toward a common goal. Consequently, the number or prestige of research workers in one company may be overshadowed by the effectiveness with which they are being helped to work as a team in another.

Nor is a management’s ability to coordinate diverse technical skills into a closely-knit team and to stimulate each expert on that team to his greatest productivity the only kind of complex coordination upon which optimum research results depend. Close and detailed coordination between research workers on each developmental project and those thoroughly familiar with both production and sales problems is almost as important. It is no simple task for management to bring about this close relationship between research, production, and sales.Yet unless this is done, new products as finally conceived frequently are either not designed to be manufactured as cheaply as possible, or, when designed, fail to have maximum sales appeal. Such research usually results in products vulnerable to more efficient competition.

Finally there is one other type of coordination necessary if research expenditures are to attain maximum efficiency. This is coordination with top management. It might perhaps better be called top management’s understanding of the fundamental nature of commercial research. Development projects cannot be expanded in good years and sharply curtailed in poor ones without tremendously increasing the total cost of reaching the desired objective. The “crash” programs so loved by a few top managements may occasionally be necessary but are often just expensive. A crash program is what occurs when important elements of the research personnel are suddenly pulled from the projects on which they have been working and concentrated on some new task which may have great importance at the moment but which, frequently, is not worth all the disruption it causes.The essence of successful commercial research is that only tasks be selected which promise to give dollar rewards of many times the cost of the research. However, once a project is started, to allow budget considerations and other extra factors outside the project itself to curtail or accelerate it invariably expands the total cost in relation to the benefits obtained.

Some top management do not seem to understand this. I have heard executives of small but successful electronic companies express surprisingly little fear of the competition of one of the giants of the industry. This lack of worry concerning the ability of the much larger company to produce competitive products is not due to lack of respect for the capabilities of the larger company’s individual researchers or unawareness of what might otherwise be accomplished with the large sums the big company regularly spends on research. Rather it is the historical tendency of this larger company to interrupt regular research projects with crash programs to attain the immediate goals of top management that has produced this feeling. Similarly, some years ago I heard that while they desired no publicity on the matter for obvious reasons, an outstanding technical college quietly advised its graduating class to avoid employment with a certain oil company. This was because top management of that company had a tendency to hire highly skilled people for what would normally be about five-year projects. Then in about three years the company would lose interest in the particular project and abandon it, thereby not only wasting their own money but preventing those employed from gaining the technical reputation for accomplishment that otherwise might have come to them.

Another factor making proper investment evaluation of research even more complex is how to evaluate the large amount of research related to defense contracts. A great deal of such research is frequently done not at the expense of the company doing it, but for the account of the federal government. Some of the subcontractors in the defense field also do significant research for the account of the contractors whom they are supplying. Should such totals be appraised by the investor as being as significant as research done at a company’s own expense? If not, how should it be valued in relation to company-sponsored research? Like so many other phases in the investment field, these matters cannot be answered by mathematical formulae. Each case is different.

The profit margin on defense contracts is smaller than that of non-government business, and the nature of the work is often such that the contract for a new weapon is subject to competitive bidding from government blueprints. This means that it is sometimes impossible to build up steady repeat business for a product developed by government sponsored research in a way that can be done with privately sponsored research, where both parents and customer goodwill can frequently be brought into play. For reasons like these, from the standpoint of the investor there are enormous variations in the economic worth of different government-sponsored research projects, even though such projects might be roughly equal in their importance so far as the benefits to the defense effort are concerned. The following theoretical example might serve to show how three such projects might have vastly different values to the investor:

One project might produce a magnificent new weapon having no non-military applications. The rights to this weapon would all be owned by the government and, once invented, it would be sufficiently simple to manufacture that the company which had done the research would have no advantage over others in bidding for a production contract. Such a research effort would have almost no value to the investor.

Another project might produce the same weapon, but the technique of manufacturing might be sufficiently complex that a company not participating in the original development work would have great difficulty trying to make it. Such a research project would have moderate value to the investor since it would tend to assure continuous, though probably not highly profitable, business from the government.

Still another company might engineer such a weapon and in so doing might learn principles and new techniques directly applicable to its regular commercial lines, which presumably show a higher profit margin. Such a research project might have great value to the investor. Some of the most spectacularly successful companies of the recent past have been those that show a high order of talent for finding complex and technical defense work, the doing of which provides them at government expense with know-how that can legitimately be transferred into profitable non-defense fields related to their existing commercial activities. Such companies are providing the government the research results the defense authorities vitally need. However, at the same time they are obtaining, at little or no cost, related non-defense research benefits which otherwise they would probably be paying for themselves. This factor may well have been one of the reasons for the spectacular investment success of Texas Instruments, Inc., which in four years rose nearly 500% from the price of 5¼ at which it traded when first listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1953; it may also have contributed, in the same period, to the even greater 700% rise experienced by Ampex shareholders from the time this company’s shares were first offered to the public in the same year.

Finally, in judging the relative investment value of company research organizations, another type of activity must be evaluated. This is something which ordinarily is not considered as developmental research at all-the seemingly unrelated field of market research. Market research may be regarded as the bridge between developmental research and sales. Top management must be alert against the temptation to spend significant sums on the research and development of a colorful product or process which, when perfected, has a genuine market but one too small to be profitable. By too small to be profitable I mean one that will never enjoy a large enough sales volume to get back the cost of the research, much less a worthwhile profit for the investor. A market research organization that can steer a major research effort of its company from one project which if technically successful would have barely paid for itself, to another which might cater to so much broader a market that it would pay out three times as well, would have vastly increased the value to its stockholders of that company’s scientific manpower.

If quantitative measurements-such as the annual expenditures on research or the number of employees holding scientific degrees-are only a rough guide and not the final answer to whether a company has an outstanding research organization, how does the careful investor obtain this information? Once again it is surprising what the “scuttle butt” method will produce. Until the average investor tries it, he probably will not believe how complete a picture will emerge if he asks intelligent questions about a company’s research activities of a diversified group of research people, some from within the company and others engaged in related lines in competitive industries, in universities, and in government. A simpler and often worthwhile method is to make a close study of how much in dollar sales or net profits has been contributed to a company by the results of its research organization during a particular span, such as the prior ten years. An organization which in relation to the size of its activities has produced a good flow of profitable new products during such a period will probably be equally productive in the future as long as it continues to operate under the same general methods.

POINT 4. Does the company have an above-average sales organization?

In this competitive age, the products or services of few companies are so outstanding that they will sell to their maximum potential if they are not expertly merchandised. It is the making of a sale that is the most basic single activity of any business.

Without sales, survival is impossible. It is the making of repeat sales to satisfied customers that is the first benchmark of success.Yet, strange as it seems, the relative efficiency of a company’s sales, advertising, and distributive organizations receives far less attention from most investors, even the careful ones, than do production, research, finance, or other major subdivisions of corporate activity.

There is probably a reason for this. It is relatively easy to construct simple mathematical ratios that will provide some sort of guide to the attractiveness of a company’s production costs, research activity, or financial structure in comparison with its competitors. It is a great deal harder to make ratios that have even a semblance of meaning in regard to sales and distribution efficiency. In regard to research we have already seen that such simple ratios are far too crude to provide anything but the first clues as to what to look for. Their value in relation to production and the financial structure will be discussed shortly. However, whether or not such ratios have anything like the value frequently placed upon them in financial circles, the fact remains that investors like to lean upon them. Recause sales effort does not readily lend itself to this type of formulae, many investors fail to appraise it at all in spite of its basic importance in determining real investment worth.

Again, the way out of this dilemma lies in the use of the “scuttle butt” technique. Of all the phases of a company’s activity, none is easier to learn about from sources outside the company than the relative efficiency of a sales organization. Both competitors and customers know the answers. Equally important, they are seldom hesitant to express their views. The time spent by the careful investor in inquiring into this subject is usually richly rewarded.

I am devoting less space to this matter of relative sales ability than I did to the matter of relative research ability. This does not mean that I consider it less important. In today’s competitive world, many things are important to corporate success. However, outstanding production, sales, and research may be considered the three main columns upon which such success is based. Saying that one is more important than another is like saying that the heart, the lungs, or the digestive tract is the most important single organ for the proper functioning of the body. All are needed for survival, and all must function well for vigorous health. Look around you at the companies that have proven outstanding investments. Try to find some that do not have both aggressive distribution and a constantly improving sales organization.

I have already referred to the Dow Chemical Company and may do so several times again, as I believe this company, which over the years has proven so rewarding to its stockholders, is an outstanding example of the ideal conservative long-range investment. Here is a company which in the public mind is almost synonymous with outstandingly successful research. However, what is not as well known is that this company selects and trains its sales personnel with the same care as it handles its research chemists. Before a young college graduate becomes a Dow salesman, he may be invited to make several trips to Midland so that both he and the company can become as sure as possible that he has the background and temperament that will fit him into their sales organization. Then, before he so much as sees his first potential customer, he must undergo specialized training that occasionally lasts only a few weeks but at times continues for well over a year to prepare him for the more complex selling jobs. This is but the beginning of the training he will receive; some of the company’s greatest mental effort is devoted to seeking and frequently finding more efficient ways to solicit from, service, and deliver to the customer.

Are Dow and the other outstanding companies in the chemical industry unique in this great attention paid to sales and distribution? Definitely not. In another and quite different industry, International Business Machines (IBM) is a company which has (speaking conservatively) handsomely rewarded its owners. An IBM executive recently told me that the average salesman spends a third of his entire time training in company-sponsored schools! To a considerable degree this amazing ratio results from an attempt to keep the sales force abreast of a rapidly dung ing technology. Nevertheless I believe it one more indication of the weight that most successful companies give to steadily improving their sales arm. A one-time profit can be made in the company which because of manufacturing or research skill obtains some worthwhile business without a strong distribution organization. However, such companies can be quite vulnerable. For steady long-term growth a strong sales arm is vital.

POINT 5. Does the company have a worthwhile profit margin?

Here at last is a subject of importance which properly lends itself to the type of mathematical analysis which so many financial people feel is the backbone of sound investment decisions. From the standpoint of the investor, sales are only of value when and if they lead to increased profits. All the sales growth in the world won’t produce the right type of investment vehicle if, over the years, profits do not grow correspondingly.

The first step in examining profits is to study a company’s profit margin, that is, to determine the number of cents of each dollar of sales that is brought down to operating profit. The wide variation between different companies, even those in the same industry, will immediately become apparent. Such a study should be made, not for a single year, but for a series of years. It then becomes evident that nearly all companies have broader profit margins-as well as greater total dollar profits-in years when an industry is unusually prosperous. However, it also becomes clear that the marginal companies-that is, those with the smaller profit margins-nearly always increase their profit margins by a considerably greater percentage in the good years than do the lower cost companies, whose profit margins also get better but not to such a great degree. This usually causes the weaker companies to show a greater percentage increase in earnings in a year of abnormally good business than do the stronger companies in the same field. However, it should also be remembered that these earnings will decline correspondingly more rapidly when the business tide turns.

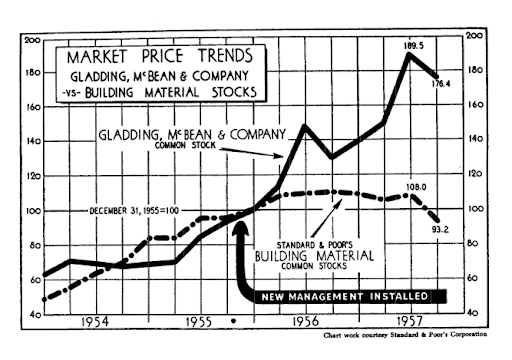

For this reason I believe that the greatest long-range investment profits are never obtained by investing in marginal companies. The only reason for considering a long-range investment in a company with an abnormally low profit margin is that there might be strong indications that a fundamental change is taking place within the company. This would be such that the improvement in profit margins would be occurring for reasons other than a temporarily expanded volume of business. In other words, the company would not be marginal in the true sense of the word, since the real reason for buying is that efficiency or new products developed within the company have taken it out of the marginal category. When such ‘internal changes are taking place in a corporation which in other respects pretty well qualifies as the right type of long-range investment, it may be an unusually attractive purchase.

So far as older and larger companies are concerned, most of the really big investment gains have come from companies having relatively broad profit margins. Usually they have among the best such margins in their industry. In regard to young companies, and occasionally older ones, there is one important deviation from this rule – a deviation, however, that is generally more apparent than real. Such companies will at times deliberately elect to speed up growth by spending all or a very large part of the profits they would otherwise have earned on even more research or on even more sales promotion than they would otherwise be doing. What is important in such instances is to make absolutely certain that it is actually still further research, still further sales promotion, or still more of any other activity which is being financed today so as to build for the future, that is the real cause of the narrow or non-existent profit margin.

The greatest care should be used to be sure that the volume of the activities being credited with reducing the profit margin is not merely the volume of these activities needed for a good rate of growth, but actually represents even more research, sales promotion, etc., than this. When this happens, the research company with an apparently poor profit margin may be an unusually attractive investment. However, with the exception of companies of this type in which the low profit margin is being deliberately engineered in order to further accelerate the growth rate, investors desiring maximum gains over the years had best stay away from low-profit-margin or marginal companies.

POINT 6. What is the company doing to maintain or improve profit margins?

The success of a stock purchase does not depend on what is generally known about a company at the time the purchase is made. Rather it depends upon what gets to be known about it after the stock has been bought. Therefore it is not the profit margins of the past but those of the future that are basically important to the investor.

In the age in which we live, there seems to be a constant threat to profit margins. Wages and salary costs go up year by year. Many companies now have long-range labor contracts calling for still further increases for several years ahead. Rising labor costs result in corresponding increases in raw materials and supplies. The trend of tax rates, particularly real estate and local tax rates, also seems to be steadily increasing. Against this background, different companies are going to have different results in the trend of their profit margins. Some companies are in the seemingly fortunate position that they can maintain profit margins simply by raising prices. This is usually because they are in industries in which the demand for their products is abnormally strong or because the selling prices of competitive products have gone up even more than their own. In our economy, however, maintaining or improving profit margins in this way usually proves a relatively temporary matter. This is because additional competitive production capacity is created. This new capacity sufficiently outbalances the increased gain so that, in time, cost increases can no longer be passed on as price increases. Profit margins then start to shrink.

A striking example of this is the abrupt change that occurred in the fall of 1956, when the aluminum market went in a few weeks from a condition of short supply to one of aggressive competitive selling. Prior to that time aluminum prices rose about with costs. Unless demand for the product should grow even faster than production facilities, future price increases will occur less rapidly. Similarly the persistent disinclination of some of the largest steel producers to raise prices of certain classes of scarce steel products to “all the market would bear” may in part reflect long-range thinking about the temporary nature of broad profit margins that arise from no other cause than an ability to pass on increased costs by higher selling prices.

The long-range danger of this is perhaps best illustrated by what happened to the leading copper producers during this same second half of 1956. These companies used considerable self-restraint, even going so far as to sell underworld prices in an attempt to keep prices from going too high. Nevertheless, copper rose sufficiently to curtail demand and attract new supply. Aggravated by curtailed Western European consumption resulting from the closing of the Suez Canal, the situation became quite unbalanced. It is probable that 1957 profit margins were noticeably poorer than would have been the case if those of 1956 had not been so good. When profit margins of a whole industry rise because of repeated price increases, the indication is not a good one for the long-range investor.

In contrast, certain other companies, including some within these same industries, manage to improve profit margins by far more ingenious means than just raising prices. Some companies achieve great success by maintaining capital-improvement or product-engineering departments. The sole function of such departments is to design new equipment that will reduce costs and thus offset or partially offset the rising trend of wages. Many companies are constantly reviewing procedures and methods to see where economies can be brought about.

The accounting function and the handling of records has been a particularly fertile field for this sort of activity. So has the transportation field. Shipping costs have risen more than most expenses because of the larger percentage of labor costs in most forms of transportation as compared to most types of manufacturing. Using new types of containers, heretofore unused methods of transportation, or even putting in branch plants to avoid cross-hauling have all cut costs for alert companies.

None of these things can be brought about in a day. They all require close study and considerable planning ahead. The prospective investor should give attention to the amount of ingenuity of the work being done on new ideas for cutting costs and improving profit margins. Here the “scuttlebutt” method may prove of some value, but much less so than direct inquiry from company personnel. Fortunately, this is a field about which most top executives will talk in some detail. The companies which are doing the most successful work along this line are very likely to be the ones which have built up the organization with the know-how to continue to do constructive things in the future. They are extremely likely to be in the group offering the greatest long-range rewards to their shareholders.

POINT 7. Does the company have outstanding labor and personnel relations?

Most investors may not fully appreciate the profits from good labor relations. Few of them fail to recognize the impact of bad labor relations. The effect on production of frequent and prolonged strikes is obvious to anyone making even the most cursory review of corporate financial statements.

However, the difference in the degree of profitability between a company with good personnel relations and one with mediocre personnel relations is far greater than the direct cost of strikes. If workers feel that they are fairly treated by their employer, a background has been laid wherein efficient leadership can accomplish much in increasing productivity per worker. Furthermore, there is always considerable cost in training each new worker. Those companies with an abnormal labor turnover have therefore an element of unnecessary expense avoided by better-managed enterprises.

But how does the investor properly judge the quality of a company’s labor and personnel relations? There is no simple answer. There is no set yardstick that will apply in all cases. About the best that can be done is to look at a number of factors and then judge from the composite picture.

In this day of widespread unionization, those companies that still have no union or a company union probably also have well above average labor and personnel relations. If they did not, the unions would have organized them long ago. The investor can feel rather sure, for example, that Motorola, located in highly unionized Chicago, and Texas Instruments, Inc., in increasingly unionized Dallas, have convinced at least an important part of their work force of the company’s genuine desire and ability to treat its employees well. Lack of affiliation with an international union can only be explained by successful personnel policies in instances of this sort.

On the other hand, unionization is by no means a sign of poor labor relations. Some of the companies with the very best labor relations are completely unionized, but have learned to get along with their unions with a reasonable degree of mutual respect and trust. Similarly, while a record of constant and prolonged strikes is a good indication of bad labor relations, the complete absence of strikes is not necessarily a sign of fundamentally good relations. Sometimes the company with no strikes is too much like the henpecked husband.Absence of conflict may not mean a basically happy relationship as much as fear of the consequences of conflict.

Why do workers feel unusually loyal to one employer and resentful of another? The reasons are often so complex and difficult to trace that for the most part the investor may do better to concern himself with comparative data showing how workers feel, rather than with an attempt to appraise each part of the background causing them to feel that way. One series of figures that indicates the underlying quality of labor and personnel policies is the relative labor turnover in one company as against another in the same area. Equally significant is the relative size of the waiting list of job applicants wanting to work for one company as against others in the same locality. In an area where there is no labor surplus, companies having an abnormally long list of personnel seeking to enter their employ are usually companies that are desirable for investment from the standpoint of good labor and personnel relations.

Nevertheless, beyond these general figures there are a few specific details the investor might notice. Companies with good labor relations usually are ones making every effort to settle grievances quickly. The small individual grievances that take long to settle and are not considered important by management are ones that smolder and finally flare up seriously. In addition to appraising the methods set up for settling grievances, the investor might also pay close attention to wage scales. The company that makes above-average profits while paying above average wages for the area in which it is located is likely to have good labor relations. The investor who buys into a situation in which a significant part of earnings comes from paying below-standard wages for the area involved may in time have serious trouble on his hands.

Finally the investor should be sensitive to the attitude of top management toward the rank-and-file employees. Underneath all the fine-sounding generalities, some managements have little feeling of responsibility for, or interest in, their ordinary workers. Their chief concern is that no greater share of their sales dollar go to lower echelon personnel than the pressure of militant unionism makes it mandatory. Workers are readily hired or dismissed in large masses, dependent on slight changes in the company’s sales outlook or profit picture. No feeling of responsibility exists for the hardships this can cause to the families affected. Nothing is done to make ordinary employees feel they are wanted, needed, and part of the business picture. Nothing is done to build up the dignity of the individual worker. Managements with this attitude do not usually provide the background for the most desirable type of investment.

POINT 8. Does the company have outstanding executive relations?

If having good relations with lower echelon personnel is important, creating the right atmosphere among executive personnel is vital.

These are the men whose judgment, ingenuity, and teamwork will in time make or break any venture. Because the stakes for which they play are high, the tension on the job is frequently great. So is the chance that friction or resentment might create conditions whereby top executive talent either does not stay with a company or does not produce to its maximum ability if it does stay.

The company offering greatest investment opportunities will be one in which there is a good executive climate. Executives will have confidence in their president and/or board chairman. This means, among other things, that from the lowest levels on up there is a feeling that promotions are based on ability, not factionalism. A ruling family is not promoted over the heads of more able men. Salary adjustments are reviewed regularly so that executives feel that merited increases will come without having to be demanded. Salaries are at least in line with the standard of the industry and the locality. Management will bring outsiders into anything other than starting jobs only if there is no possibility of finding anyone within the organization who can be promoted to fill the position. Top management will recognize that wherever human beings work together, some degree of factionalism and human friction will occur, but will not tolerate those who do not cooperate in team play so that such friction and factionalism is kept to an irreducible minimum. Much of this the investor can usually learn without too much direct questioning by chatting about the company with a few executives scattered at different levels of responsibility. The further a corporation departs from these standards, the less likely it is to be a really outstanding investment.

POINT 9. Does the company have depth to its management?

A small corporation can do extremely well and, if other factors are right, provide a magnificent investment for a number of years under really able one-man management. However, all humans are finite, so even for smaller companies the investor should have some idea of what can be done to prevent corporate disaster if the key man should no longer be available. Nowadays this investment risk with an otherwise outstanding small company is not as great as it seems, in view of the recent tendency of big companies with plenty of management talent to buy up outstanding smaller units.

However, companies worthy of investment interest are those that will continue to grow. Sooner or later a company will reach a size where it just will not be able to take advantage of further opportunities unless it starts developing executive talent in some depth.This point will vary between companies, depending on the industry in which they are engaged and the skill of the one-man management. It usually occurs when annual sales totals reach a point somewhere between $15 million and $40 million. Having the right executive climate, as discussed in Point 8, becomes of major investment significance at this time.

Those matters discussed in Point 8 are, of course, needed for development of proper management in depth. But such management will not develop unless certain additional policies are in effect as well. Most important of these is the delegation of authority. If from the very top on down, each level of executives is not given real authority to carry out assigned duties in an ingenious and efficient manner as each individual’s ability will permit, good executive material becomes much like healthy young animals so caged in that they cannot exercise. They do not develop their faculties because they just do not have enough opportunity to use them.

Those organizations where the top brass personally interfere with and try to handle routine day-to-day operating matters seldom turn out to be the most attractive type of investments. Cutting across the lines of authority which they themselves have set up frequently results in well-meaning executives significantly detracting from the investment caliber of the companies they run. No matter how able one or two bosses may be in handling all this detail, once a corporation reaches a certain size executives of this type will get in trouble on two fronts. Too much detail will have arisen for them to handle. Capable people just are not being developed to handle the still further growth that should lie ahead.

Another matter is worthy of the investor’s attention in judging whether a company has suitable depth in management. Does top management welcome and evaluate suggestions from personnel even if, at times, those suggestions carry with them adverse criticism of current management practices? So competitive is today’s business world and so great the need for improvement and change that if pride or indifference prevent top management from exploring what has frequently been found to be a veritable gold mine of worthwhile ideas, the investment climate that results probably will not be the most suitable one for the investor. Neither is it likely to be one in which increasing numbers of vitally needed younger executives are going ro develop.

POINT 10. How good are the company’s cost analysis and accounting controls?

No company is going to continue to have outstanding success for a long period of time if it cannot break down its overall costs with sufficient accuracy and detail to show the cost of each small step in its operation. Only in this way will management know what most needs its attention. Only in this way can management judge whether it is properly solving each problem that does need its attention. Furthermore, most successful companies make not one but a vast series of products. If the management does not have a precise knowledge of the true cost of each product in relation to the others, it is under an extreme handicap. It becomes almost impossible to establish pricing policies that will insure the maximum obtainable over-all profit consistent with discouraging undue competition. There is no way of knowing which products are worthy of special sales effort and promotion. Worst of all, when apparently successful activities may actually be operating at a loss and, unknown to management, may be decreasing rather than swelling the total of over-all profits. Intelligent planning becomes almost impossible.

In spite of the investment importance of accounting controls, it is usually only in instances of extreme inefficiency that the careful investor will get a clear picture of the status of cost accounting and related activities in a company in which he is contemplating investment. In this sphere, the “scuttlebutt” method will sometimes reveal companies that are really deficient. It will seldom tell much more than this. Direct inquiry of company personnel will usually elicit a completely sincere reply that the cost data are entirely adequate. Detailed cost sheets will often be shown in support of the statement. However, it is not so much the existence of detailed figures as their relative accuracy which is important. The best that the careful investor usually can do in this field is to recognize both the importance of the subject and his own limitations in making a worthwhile appraisal of it. Within these limits he usually can only fall back on the general conclusion that a company well above average in most other aspects of business skill will probably be above average in this field, too, as long as top management understands the basic importance of expert accounting controls and cost analysis.

POINT 11. Are there other aspects of the business, somewhat peculiar to the industry involved, which will give the investor important clues as to how outstanding the company may be in relation to its competition?

By definition, this is somewhat of a catch-all point of inquiry. This is because matters of this sort are bound to differ considerably from each other – those which are of great importance in some lines of business can, at times, be of little or no importance in others. For example, in most important operations involving retailing, the degree of skill a company has in handling real estate matters – the quality of its leases, for instance – is of great significance. In many other lines of business, a high degree of skill in this field is less important. Similarly, the relative skill with which a company handles its credits is of great significance to some companies, of minor or no importance to others. For both these matters, our old friend the “scuttlebutt” method will usually furnish the investor with a pretty clear picture. Frequently his conclusions can be checked against mathematical ratios such as comparative leasing costs per dollar of sales, or ratio of credit loss, if the point is of sufficient importance to warrant careful study.

In a number of lines of business, total insurance costs mount to an important per cent of the sales dollar. At times this can matter enough so that a company with, say, a 35% lower overall insurance cost than a competitor of the same size will have a broader margin of profit. In those industries where insurance is a big enough factor to affect earnings, a study of these ratios and a discussion of them with informed insurance people can be unusually rewarding to the investor. It gives a supplemental but indicative check as to how outstanding a particular management may be. This is because these lower insurance costs do not come solely from a greater skill in handling insurance in the same way, for example, a skill in handling real estate results in lower than average leasing costs. Rather they are largely the reflection of overall skill in handling people, inventory, and fixed property so as to reduce the overall amount of accident, damage, and waste and thereby make these lower costs possible. An index of insurance costs in relation to the coverage obtained points out clearly which companies in a given field are well run.

Patents are another matter having varying significance from company to company. For large companies, a strong patent position is usually a point of additional rather than basic strength. It usually blocks off certain subdivisions of the company’s activities from the intense competition that might otherwise prevail. This normally enables these segments of the company’s product lines to enjoy wider profit margins than would otherwise occur. This in turn tends to broaden the average of the entire line. Similarly, strong patent positions may at times give a company exclusive rights to the easiest or cheapest way of making a particular product. Competitors must go a longer way round to get to the same place, thereby giving the patent owner a tangible competitive advantage although frequently a small one.

In our era of widespread technical know-how it is seldom that large companies can enjoy more than a small part of their activities in areas sheltered by patent protection. Patents are usually able to block off only a few rather than all the ways of accomplishing the same result. For this reason many large companies make no attempt to shut out competition through patent structure, but for relatively modest fees license competition to use their patents and in return expect the same treatment from these licensees. Influences such as manufacturing know-how, sales and service organization, customer goodwill, and knowledge of customer problems are depended on far more than patents to maintain a competitive position. In fact, when large companies depend chiefly on patent protection for the maintenance of their profit margin, it is usually more a sign of investment weakness than strength. Patents do not run on indefinitely. When the patent protection is no longer there, the company’s profit may suffer badly.

The young company is just starting to develop its production, sales, and service organization, and in the early stages of establishing customer goodwill is in a very different position. Without patents its products might be copied by large entrenched enterprises which could use their established channels of customer relationship to put the small young competitor out of business. For small companies in the early years of marketing unique products or services, the investor should therefore closely scrutinize the patent position. He should get information from qualified sources as to how broad the protection actually may be. It is one thing to get a patent on a device. It may be quite another to get protection that will prevent others from making it in a slightly different way. Even here, however, engineering that is constantly improving the product can provide considerably more advantageous than mere static patent protection.

For example, a few years ago when it was a much smaller organization than as of today, a young West Coast electronic manufacturer had great success with a new product. One of the giants of the industry made what was described to me as a “Chinese copy” and marketed it under its well-known trade name. In the opinion of the young company’s designer, this large competitor managed to engineer all the small company’s engineering mistakes into the model along with the good points. The large company’s model came out at just the time the small manufacturer introduced its own improved model with the weak points eliminated. With a product that was not selling, the large company withdrew from the field. As has been true many times before and since, it is the constant leadership in engineering, not patents, that is the fundamental source of protection. The investor must be at least as careful not to place too much importance on patent protection as to recognize its significance in those occasional places where it is a major factor in appraising the attractiveness of a desirable investment.

POINT 12. Does the company have a short-range or long-range outlook in regard to profits?

Some companies will conduct their affairs so as to gain the greatest possible profit right now. Others will deliberately curtail maximum immediate profits to build up good will and thereby gain greater overall profits over a period of years. Treatment of customers and vendors gives frequent examples of this. One company will constantly make the sharpest possible deals with suppliers. Another will at times pay above contract price to a vendor who has had unexpected expenses in making delivery, because it wants to be sure of having a dependable source of needed raw materials or high-quality components available when the market has turned and supplies may be desperately needed. The difference in treatment of customers is equally noticeable. The company that will go to special trouble and expense to take care of the needs of a regular customer caught in an unexpected jam may show lower profits on the particular transaction, but far greater profits over the years.

The “scuttlebutt” method usually reflects these differences in policies quite clearly. The investor wanting maximum results should favor companies with a truly long-range outlook concerning profits.

POINT 13. In the foreseeable future will the growth of the company require sufficient equity financing so that the larger number of shares then outstanding will largely cancel the existing stockholders’ benefit from this anticipated growth?

The typical book on investment devotes so much space to a discussion on the corporation’s cash position, corporate structure, percentage of capitalization in various classes of securities, etc., that it may well be asked why these purely financial aspects should not be given more than the amount of space devoted to this view point out of a total of 15. The reason is that it is the basic contention of this book that the intelligent investor should not buy common stocks simply because they are cheap but only if they give promise of major gain to him.

Only a small percentage of all companies can qualify with a high rating for all or nearly all of the other fourteen points listed in this discussion. Any company which can so qualify could easily borrow money, at prevailing rates for its size company, up to the accepted top percentage of debt for that kind of business. If such a company needed more cash once this top debt limit has been reached – always assuming of course that it qualifies at or near the top in regard to further sales growth, profit margins, management, research, and the various other points we are now considering – it could still raise equity money at some price, since investors are always eager to participate in ventures of this sort.

Therefore, if investment is limited to outstanding situations, what really matters is whether the company’s cash plus further borrowing ability is sufficient to take care of the capital needed to exploit the prospects of the next several years. If it is, and if the company is willing to borrow to the limit of prudence, the common stock investor need have no concern as to the more distant future. If the investor has properly appraised the situation, any equity financing that might be done some years ahead will be at prices so much higher than present levels that he need not be concerned. This is because the near-term financing will have produced enough increase in earnings, by the time still further financing is needed some years hence, to have brought the stock to a substantially higher price level.

If this borrowing power is not now sufficient, however, equity financing becomes necessary. In this case, the attractiveness of the investment depends on careful calculations as to how much the dilution resulting from the greater number of shares to be outstanding will cut into the benefits to the present common stockholder that will result from the increased earnings this financing makes possible. This equity dilution is just as mathematically calculable when the dilution occurs through the issuance of senior securities with conversion features as when it occurs through the issuance of straight common stock. This is because such conversion features are usually exercisable at some moderate level above the market price at the time of issuance – usually from 10% to 20%. Since the investor should never be interested in small gains of 10% to 20%, but rather in gains which over a period of years will be closer to ten or a hundred times this amount, the conversion price can usually be ignored and the dilution calculated upon the basis of complete conversion of the new senior issue. In other words, it is good to consider that all senior convertible issues have been converted and that all warrants, options, etc., have been exercised when calculating the real number of common shares outstanding.

If equity financing will be occurring within several years of the time of common stock purchase, and if this equity financing will leave common stockholders with only a small increase in subsequent per-share earnings, only one conclusion is justifiable. This is that the company has a management with sufficiently poor financial judgment to make the common stock undesirable for worthwhile investment. Unless this situation prevails, the investor need not be deterred by purely financial considerations from going into any situation which, because of its high rating on the remaining fourteen points covered, gives promise of being outstanding. Conversely, from the standpoint of making maximum profits over the years, the investor should never go into a situation with a poor score on any of the other fourteen points, merely because of great financial strength or cash position.

POINT 14. Does the management talk freely to investors about its affairs when things are going well but “clam up” when troubles and disappointments occur?

It is the nature of business that in even the best-run companies unexpected difficulties, profit squeezes, and unfavorable shifts in demand for their products will at times occur.

Furthermore, the companies into which the investor should be buying if greatest gains are to occur are companies which over the years will constantly, through the efforts of technical research, be trying to produce and sell new products and new processes. By the law of averages, some of these are bound to be costly failures. Others will have unexpected delays and heartbreaking expenses during the early period of plant shake-down. For months on end, such extra and unbudgeted costs will spoil the most carefully laid profit forecasts for the business as a whole. Such disappointments are an inevitable part of even the most successful business. If met forthrightly and with good judgment, they are merely one of the costs of eventual success. They are frequently a sign of strength rather than weakness in a company.

How a management reacts to such matters can be a valuable clue to the investor. The management that does not report as freely when things are going badly as when they are going well usually “clams up” in this way for one of several rather significant reasons. It may not have a program worked out to solve the unanticipated difficulty. It may have become panicky. It may not have an adequate sense of responsibility to its stockholders, seeing no reason why it should report more than what may seem expedient at the moment. In any event, the investor will do well to exclude from investment any company that withholds or tries to hide bad news.

POINT 15. Does the company have a management of unquestionable integrity?

The management of a company is always far closer to its assets than is the stockholder. Without breaking any laws, the number of ways in which those in control can benefit themselves and their families at the expense of the ordinary stockholder is almost infinite. One way is to put themselves – to say nothing of their relatives or in-laws – on the payroll at salaries far above the normal worth of the work performed. Another is to own properties they sell or rent to the corporation at above-market rates.Among smaller corporations this is sometimes hard to detect, since controlling families or key officers at times buy and lease real estate to such companies, not for purposes of unfair gain but in a sincere desire to free limited working capital for other corporate purposes.

Another method for insiders to enrich themselves is to get the corporation’s vendors to sell through certain brokerage firms, which perform little if any service for the brokerage commissions involved but which are owned by these same insiders and relatives or friends. Probably most costly of all to the investor is the abuse by insiders of their power of issuing common stock options. They can pervert this legitimate method of compensating able management by issuing to themselves amounts of stock far beyond what an unbiased outsider might judge to represent a fair reward for services performed.

There is only one real protection against abuses like these. This is to confine investments to companies the managements of which have a highly developed sense of trusteeship and moral responsibility to their stockholders. This is a point concerning which the “scuttlebutt” method can be very helpful. Any investment may still be considered interesting if it falls down in regard to almost any other one of the fifteen points which have now been covered, but rates an unusually high score in regard to all the rest. Regardless of how high the rating may be in all other matters, however, if there is a serious question of the lack of a strong management sense of trusteeship for stockholders, the investor should never seriously consider participating in such an enterprise.

Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings, by Philip A. Fisher, published with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD