Lessons From a Distressed Investing Legend

Negotiating With Union Leaders, Warren Buffett, and Bankrupt Banks

| Editor’s Note: Porter & Co. follows a lighter publishing schedule in August, but we continue to monitor all of our portfolios, and will send updates and buy and sell alerts on our open positions when needed for all services. This August, we’re launching a special series called “What We’re Reading.” Each Friday during the month, we are sending Big Secret readers a literary excerpt or investing insight that you won’t see anywhere else. We have asked the analysts at Porter & Co. to share an excerpt from their personal summer reading – books that they found instructive, or ones that they just plain enjoyed. We hope you’ll enjoy them too. We’re kicking off this month’s program with “what Marty’s reading”… Martin Fridson, who leads our Distressed Investing advisory, has secured an advance copy of Risks and Returns, the upcoming memoir of the legendary “King of Bankruptcy” Wilbur Ross… and he’s graciously agreed to share a part of it with us. The full book will be released in September, and you can pre-order it here. Marty also shares his insights into Ross’ colorful career in his brief introduction below. If you like “What We’re Reading,” let us know – and let us know what you are reading by sharing your current book list to [email protected]. In addition to hosting this issue on our website, we also make it available as a downloadable PDF. Click here to download the full issue. |

Wilbur Ross was called “King of Bankruptcy” during his long and distinguished Wall Street career. Ross earned that distinction because of his mastery of the U.S. bankruptcy process, which is essential to understanding distressed securities.

Ross headed up bankruptcy restructuring for decades at global investment bank Rothschild & Sons before starting his own firm, W.L. Ross & Co., in 2000. In 2016, President Donald Trump appointed him Secretary of Commerce, a position he held until 2021.

Ross has granted an exclusive advance look to Porter & Co. of his upcoming memoir, Risks and Returns: Creating Success in Business and Life. The excerpt offers the perspective of an investment banker who engaged in the nitty-gritty of negotiations among distressed companies and their creditors. During many of these negotiations, Ross acquired prominent businesses out of bankruptcy and managed their successful turnarounds, earning him and the bondholders handsome profits. That experience provides readers a fresh viewpoint as someone who was in the game – commentaries on bankruptcy are more commonly authored by securities analysts and lawyers.

He begins this essay by sharing a story that sheds light on the importance of labor relations in reviving failed companies, notably in the account of W.L. Ross & Co.’s 2002 acquisition of the steel subsidiaries of Ling-Temco-Vought. Prior to his involvement, the business suffered huge inefficiencies because of internal bureaucracies. For instance, the maintenance team and the operators of a company mill knew how to do each other’s jobs, but if the mill broke down, the operators would sit around playing cards while the maintenance people took over. Ross used a cooperative rather than a confrontational approach with the union to streamline the organizational structure, creating a single, unified team that more efficiently ran and repaired the mill.

Ross also recounts how he outmaneuvered Warren Buffett to win the bidding for the bankrupt Burlington Mills textile company. He also grappled with organized crime in advising the Italian government on restructuring Banco di Napoli. The bottom line is that distressed-debt investors will profit richly from the insights Wilbur Ross gained through his wide-ranging creation of value out of financial failure. – Martin Fridson

The Art of the Steel

One of W.L. Ross & Co.’s first investments was buying the conglomerate Ling-Temco-Vought’s (“LTV”) steel subsidiaries in 2002. I had previously advised the unsecured creditors of LTV in its first bankruptcy in 1986. Now the company was bankrupt again, and this time poised for liquidation. The steel mill was kept on “hot idle,” with just enough molten metal running through it to prevent the mill’s refractory bricks from imploding. That process was costing more than $1 million per week, so creditors were scrambling to auction off the mill.

We studied the business and formed International Steel Group (“ISG”) in anticipation of submitting a bid for it. In the meantime, a bankruptcy court had already terminated the unfunded pension and retiree healthcare obligations, and the workers almost all had been let go. ISG was optimistic about acquiring the mill, but a terrible labor contract had to be fixed before we could submit a bid.

I called Leo Gerard, president of the United Steelworkers of America (“USWA”) union, and told him of our interest in purchasing LTV’s steel operation. He and I soon met in Pittsburgh. ISG proposed to hire back most of the former workers, but to do so on a “nonconforming” contract – meaning that it had more favorable terms than the other steel industry contracts. In exchange, we needed to reduce the number of job classifications from 32 to five.

The existing number of categories created artificial restrictions on who could do what, leading to gross inefficiencies. For example, the operators of a rolling mill and its maintenance team each knew how to do each other’s jobs. But for weeks, maintenance men would sit around playing pinochle until the mill broke down. Then the operators would play pinochle for a few days while the maintenance guys went to work. This structure was simply too wasteful – we needed only one set of workers to both operate and maintain the mill.

As for wages, we left them unchanged, but cut out excess days off. Overtime pay would kick in after 40 hours in a week, instead of beginning each day after eight hours of work. That let us offset overtime on one day with fewer hours on another day. Finally, only people who actually touched steel would be USWA union members, not office workers. The quid pro quo for all this was that we set weekly targets for each shift on each machine and if the workers hit their production targets everyone involved would get a bonus, even if the company was losing money overall.

I am a great believer in productivity bonuses for blue-collar workers. Unions dislike them because they prefer to be the exclusive intermediary between a worker and his paycheck.

At first, Leo, the union president, gagged on these radical proposals. But we broke for two hours and then met at his favorite Italian restaurant, up high on a hill overlooking Pittsburgh. There, while consuming gallons of red wine, we inked an agreement in longhand on a napkin. At the end, I had one more condition: The contract must be applicable to any other steel company we acquired.

Leo was fine with it, but had another stipulation of his own: We must implement our plan to reduce the layers of management from factory floor to CEO office from eight to three. This reduction accelerated decision-making and gave the CEO better firsthand knowledge of what was going on. We also agreed that the CEO’s base pay could not exceed 10 times what an experienced steelworker received, but there could be very large performance-based bonuses.

Separately, W.L. Ross & Co. convinced Cleveland-Cliffs to supply iron ore not on a fixed price, but rather one that varied with the price of hot rolled sheet, our most basic product. This locked in our gross margins.

Not everyone in the steel industry looked favorably on the deal we had made with the unions. I soon received an unsolicited call from the CEO of U.S. Steel. The company historically has had a difficult relationship with the steelworkers’ unions.

“Wilbur, I don’t know you well, but I am calling to do you a real favor,” the U.S. Steel CEO began. “You are making the biggest mistake of your life by trusting the steelworkers. If you buy LTV, they will f— you. Believe me, I have dealt with them for years. Don’t do the deal.”

I thanked him and hung up, convinced that, more than anything, he was worried that we might outcompete him. Indeed, our negotiation style was a competitive advantage. Typically, major industrial labor negotiations involve battalions of lawyers and public relations professionals hired by management. Unions then feel compelled to take up arms in the same way. There is little one-on-one negotiation, and the experts play head games with each other. Leo and I saved time and money by working out the key bullet points in one session and then tasking the lawyers to write out the details. I truly believe our ability to do this deal with the UWSA saved as many as 100,000 jobs.

Trust as a Powerful Business Tool

This situation was somewhat special in our level of trust in one another. As I’d seen in other bankruptcies, I realized during our talks that the union understood the company better than the senior management. Hence, they had a realistic sense of why the operation was failing, and why they needed to give concessions toward a lower-cost operation.

For my part, I won Leo’s trust by showing him how cost savings could happen by streamlining job categories, and by demonstrating a good-faith interest in the welfare of his workers by promising productivity bonuses. Nor did I mind having a union representative on the board of directors. American companies actually get off easy if a single union rep is a voting board member – European companies often feature much greater union representation.

These talks reinforced that one of the most important relationships for any CEO must be with the head of his or her union. It should not just be a business relationship, but also have a social component. And it certainly should not be adversarial. This general posture also helped explain why the various auto parts businesses I was involved in never went on strike at the time I controlled them. In 2003, a Slate headline wondered “Is Wilbur Ross the Next Andrew Carnegie?” The answer was no – at least where relations with the unions were concerned.

Three weeks after my meeting with Leo, in a blinding snowstorm, at the Cleveland office of the law firm Jones Day, ISG was the only bidder for LTV, though U.S. Steel and others came to watch the proceeding. For $325 million, we bought $90 million in fixed assets, into which $2.5 billion had been invested just in the last five years. The deal also included $100 million of accounts receivable and inventory worth $50 million, which GE Capital financed 100% for us.

But the best part was that the union fully honored the deal Leo and I had scrawled on napkins. We reduced the number of man-hours to make a ton of steel from close to six to one and a half. For years afterward, I kept up good relations with Leo and the USWA union to let them know I truly regarded them as partners, and that we were mutually dependent on each other for prosperity – almost like we held each other hostage.

Once, I went to a USWA picnic in a public park outside Pittsburgh. I showed up wearing my International Steel Group workman’s jacket, blue jeans, and sneakers. U.S. Steel’s two representatives wore Ralph Lauren blazers, Hermès ties, and Gucci loafers. The sartorial contrast symbolized a difference in attitude that was not lost on the union.

Helping a Steel Mill Prosper

Not long after the LTV acquisition, several factors caused International Steel Group to prosper. For one thing, China was in the throes of a building boom, pushing the price of steel higher. Second, the new labor contract had begun to return the mill to profitability. Third, U.S. automakers were pushing 0% financing, goosing demand for vehicles. Finally, Leo Gerard and I successfully lobbied the Bush administration to put a temporary tariff on imports so we would have time to requalify our newly reorganized mills with our big customers.

I had in fact been closely monitoring the public communications from the International Trade Commission prior to the LTV acquisition, and was optimistic the Bush administration would apply tariffs. They did, at a 30% clip, and LTV benefited immensely. This shows the virtue of paying strict attention to how policy decisions in Washington can impact your business.

The next year, 2003, the legacy steelmaker Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy and was careening toward liquidation. Their lawyers soon realized that our contract with the union was applicable to any steel company we bought, and approached us about making a bid. This provides yet more evidence that good relations with the union were a net benefit: No one operating on the old contract could compete with us, and Leo was not willing to give anyone else the same concession because he believed in ISG.

We managed to buy Bethlehem by just paying the professional fees of the lawyers, accountants, and financial advisors involved in the deal, with no significant payments by us to unsecured creditors. The labor contract also needed the usual membership ratification, so we arranged for Bethlehem’s shop stewards to visit counterparts at the mills ISG already owned. The result was an almost unprecedented 80% favorable vote to ratify a concessionary contract.

Two strange situations developed next. First, there were a few Bethlehem plant managers we wanted to retain, but most of them said they could not operate under the leaner management structure the labor contract called for. They quit. The thought of a 40-year-old executive preferring unemployment to accepting more responsibility is incomprehensible to me.

The second weird thing was the board’s insistence that we address its meeting when it considered our deal. It was a silly concept, because they really had no other option for a buyer. But our CEO Rodney Mott and I went to the board meeting at the Bethlehem (Pennsylvania) County Club. Much to our surprise, we arrived to see not just the board, but top management, financial advisors, and lawyers – about 50 people in total.

We went around and politely introduced ourselves. After a half hour, the CEO asked where the rest of our team was. “They’re busy making steel!” we said. Each director spoke for a few minutes to weigh in on what they thought about the deal. The most common suggestion regarding the transaction was that we keep the name Bethlehem for the newly merged company. Bethlehem was synonymous with the glory days of American steelmaking, having supplied the steel for the Lincoln Tunnel, the Empire State Building, and many of the U.S. Navy vessels for World War II.

After all of them spoke, we responded, “Bethlehem is indeed an iconic name, but today’s reality is that you have failed, and the name now has a pejorative connotation. So we can’t use it.” They grudgingly voted for the deal anyway. Had they not, Bethlehem would have been liquidated.

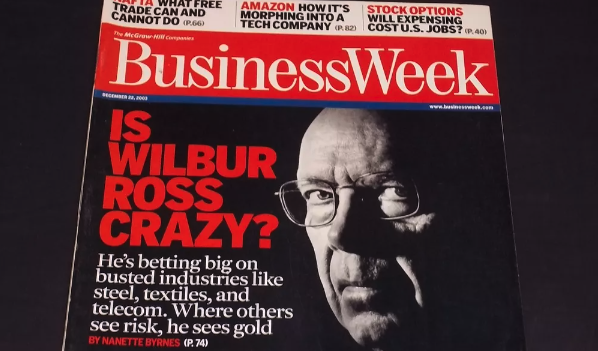

A few months later we took ISG public, with Goldman Sachs and UBS leading the initial public offering (“IPO”). Because of my appetite for purchasing money-losing steel mills, BusinessWeek published a cover story entitled, “Is Wilbur Ross Crazy?” Months later, ISG stock subsequently traded above its IPO issue price. My wife, Hilary, is still not 100% convinced that the question posed by BusinessWeek has yet been fully answered.

Negotiating As a Reasonable Accommodation

Having done thousands of business negotiations in my life, I think I’ve learned something about how the process works. Conceptually, a negotiation is primarily two people each trying to sell ideas to each other. You should not view this as a debate in which someone will win and someone else will lose. Instead, you should think of it as two friendly adults trying hard to accommodate each other’s reasonable needs.

Therefore, you should view yourself as a salesman, and adopt those qualities. Your task is to make the other party feel comfortable interacting with you. Your demeanor should be polite and attentive, and you should work hard at keeping the personal chemistry good. Aggressive behavior usually just makes the other person more defensive and belligerent – don’t lose your temper. Bullying is also counterproductive, since most executives are sufficiently strong personalities to resist it. Avoid playing head games or being tricky.

A successful negotiation begins well before you even get to the negotiating table. Preparation is as essential to a negotiation as it is to any other aspect of business decision-making. An ill-prepared negotiator may well omit a key point early on and therefore be forced to return to it later. Doing so may cause contempt for you in the mind of the other side.

Making a mistake, or worse yet, misrepresenting something, only does harm. You above all must be thoroughly prepared, not just about your side’s desires but also about what are likely to be the fundamental needs of the other side.

Once talks get underway, I like to begin negotiations with the topics likely to be the easiest to resolve. That creates a sense of momentum and even goodwill. Establishing a deadline for concluding the talks is useful, but only if it is truly a hard deadline. Setting artificial deadlines is not useful. Violating them can create a sense that there is a lack of progress.

A good practice for corporate negotiators is that the to-and-fro should occur in the conference room, not the press room. It is rarely useful to be publicly critical of your counterparty. Once people have taken a public position on a negotiation, it becomes twice as hard to make a deal.

Fine Tuning the Art of Negotiation

The one exception I have encountered is Donald Trump. He is so used to being attacked publicly and to counter attacking his adversaries in public that he doesn’t care about it. He regards tumultuous statements as just part of the game. My negotiations with him over the Trump Taj Mahal bankruptcy, proved the point.

Setting expectations for outcomes is also key. With professional negotiators involved, no one is going to crush the other one 90 to 10. The real question is how much can you marginally tilt the outcome to your benefit, perhaps 60 to 40?

People who overplay their hand by insisting on unrealistic terms rarely achieve a satisfactory result. My general rule is that if each side feels it gave a bit too much away, it is probably a reasonable deal. If you pay careful attention to the initial give and take, you can begin to estimate the other party’s determination to get things their way, and react accordingly.

Consequently, tradeoffs are useful negotiation tools. But deploy them sparingly, because they can have real financial and economic consequences. If you have gone back and forth repeatedly on the same topic without resolving it, introducing a tradeoff can jump start a path to agreement by making a lesser concession on a closely related topic that is within your tolerance. In some cases, noneconomic concessions like the company name or board representation for the company being acquired can buy you tangible economic benefits. Describing a transaction as a merger of equals, as J.P. Morgan did with Guaranty Trust, is often worth a lot, even if it may not be precisely accurate. You should be open to conceding such intangible matters in order to avoid sacrificing core interests.

Patience and polite persistence are virtues in negotiation. Part of your preparation should be developing multiple reasons why the other party should accept your request. Patiently reminding him how beneficial the deal is for his constituents is one of the best means of persuasion. But don’t trot out every rationale right at the beginning. Wheel them out one by one so you can perhaps wear down his resistance by compounding one compelling reason on top of another. Similarly, preparing in advance your rationale for not granting a concession likely to be requested will lower the temperature. If the counterparty invokes many issues you were not expecting, one of you is missing the boat.

Appealing to precedent can be useful as a winning argument. If you can show that your requests are consistent with those that have been honored in lots of prior deals in a given industry, all the better. It is even better to show that you personally have gotten in prior deals what you are seeking now, or that another company has yielded the point in a prior transaction.

When there is serious disagreement on the price of an asset, the way to bridge the gap may be to grant a higher price that only will be fully paid if the forecast results for the next few years have been achieved. In this way, the downstroke should be a bit less than you would have paid without any contingencies. That way you will have lowered your economic risk in the event of an operational shortfall. You also will want the triggering events to be measurable, simple, and difficult to manipulate. If stock is the earnout currency, you will need to make a value judgment whether to issue it at today’s price or a future one. I tend to prefer today’s price, largely to eliminate another uncontrollable variable.

There are a few other things to avoid in any negotiation. Accusing the counterparty of reneging is not useful. Simply repeating your argument about the merits of your original proposal in a calm manner is far better. If a negotiation is fraught with re-trades, it may be a signal of either party’s insincerity, and perhaps foreshadow a contentious post-deal environment. It is, of course, a very bad idea for you yourself to renege. Being well prepared and careful should eliminate any need to re-trade on your part.

Next, sessions should not run late into the night. Tired people become grouchy, and that is not useful. Tiredness can also cause people to miss points of discussion. Similarly, there should be frequent breaks during the day for similar reasons, but there should not be long delays between sessions. Talks should be in person rather than by Zoom, to the extent possible, to make it easier for personal rapport to develop.

The Art of the Bluff Is Not To

Unlike fine wine, negotiations do not get better with age. If they drag on, deal fatigue sets in, small issues assume outsized importance, and mutual distrust and even dislike can emerge. I also feel strongly that the fewer people in the negotiations room, the better. The presence of a big audience increases the risk of long speeches, less candor, and attempts at gamesmanship. Ultimately, a negotiation will be reduced to a question of who is more willing to walk away if his threshold demands are not met. If you are the one willing to walk – truly willing – and you handle yourself sensibly, the other party ultimately will realize he has a binary decision to make: Either yield to your core demands or lose the deal.

Unfortunately, in many situations neither you nor your counterparty is really prepared to blow the deal, so neither is willing to walk away from a stalemate. Under those circumstances, the best approach may be to declare a moratorium on the discussion for a couple of days. During that time, either side may decide to yield or to walk away. If it ends, at least it will be after careful reconsideration.

The biggest mistake in negotiations is to set a formal redline, because if you do so and then go beyond it, you will have lost all credibility. In poker, bluffing can be a useful part of the game strategy, if it is not overused. But I have almost never seen it work in real life when serious and well-informed people are involved. Similarly, storming out of a room only works if the other side’s approach is so unreasonable and filled with braggadocio that you need to show that you will not put up with it.

Allowing yourself to lose your temper can do no good, only harm. Emotion is the mortal enemy of rational discussion. If you catch yourself starting to become emotional, call for a break until you can calm yourself. If the other party starts to flare up, a break again is useful.

These little tips do not guarantee success. But I can guarantee that if you do the opposite of each prescription, you will have a lower probability of a successful outcome. Movies and television create larger-than-life stereotypes that make corporate negotiations seem more like hand-to-hand combat than they really are. If you want to succeed as a negotiator, cast these overly dramatic visualizations out of your mind. If you doubt my thinking, tell me the last time you convinced your spouse to do what you wanted by screaming at him or her.

I rest my case.

Sago Mine: The Worst Tragedy

Like the steel industry, the U.S. coal industry was also undergoing a hard time in the early 2000s. We created International Coal Group (“ICG”) by buying nonunion bankrupt mines, mainly in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Illinois. Months after we purchased them, they were turning around nicely, in large part because of the excellent management of Ben Hatfield, whom we had hired as ICG’s CEO. We ran them responsibly, even honoring all of the environmental remediation obligations left after the bankruptcy, perhaps becoming the only coal company to do so.

Underground coal mining is inherently a difficult and dangerous occupation. Working eight hours in a cramped space thousands of feet below the surface is the ultimate claustrophobic task, and despite highly regulated safety precautions, any incident can destroy lives. When coal miners leave their wives to go to work, the goodbyes are almost as emotional as those from wives of fighter pilots going off on combat missions.

To help ensure the safest working environment possible, ICG specifically included a strong track record of mine safety as a determinant of our executive compensation packages. Ben had stressed in his job interview for the CEO position that no mine under his supervision had ever had a fatality, so we had confidence in his ability to adhere to the rules. The mine-safety protocols held that prior to a whole shift going underground, one person would go down alone to look carefully for anything that might endanger his fellow workers as they joined him. This policy was followed meticulously and carefully recorded.

Nonetheless, before dawn on January 2, 2006, a day with powerful storms and lightning strikes, Ben called to say that an explosion at our Sago Mine in West Virginia had trapped 13 men underground. Rescue efforts were underway, but the outcome was uncertain.

I had owned the mine all of seven weeks, but still felt a responsibility to help. I volunteered to fly there to do what I could, but Ben admonished that since I had no technical skills to offer, I would just get in the way. We spoke repeatedly over the next hours and days, but an initially optimistic assessment tragically proved incorrect. All but one of the men were dead, and the sole survivor was close to death. This was the worst coal-mining disaster in years. Accordingly, state and federal authorities carefully investigated it, and ultimately concluded that the probable cause was a freak lightning bolt igniting the methane gas typically present in the mine.

Nonetheless, some of our employees had died, and their families were inconsolable. I had lost my own father at age 18, so I knew the pain the children were going through. Compounding the grief of the families and the communities was that the media initially reported that 12 of the miners were found alive – something that had to be recanted later.

We could not make up for their loss of loved ones, but at least we could provide financial support to relieve that aspect of the tragedy. I established and was the main contributor to a 501(c)(3) charity, the Sago Mine Fund, and asked then West Virginia Governor Joe Manchin to appoint an independent board of trustees to allocate the fund’s money. As a Democrat, Manchin could have made a huge political issue about a disaster at a nonunion mine owned by a private equity fund, but he knew that ICG was a responsible company and chose not to do so. I was also grateful to Donald Trump in those days, who made an unsolicited and anonymous contribution to the fund, an especially generous act.

In the wake of the tragedy, our public relations experts had recommended that I make no public response to the vast amount of press coverage that ensued. But, as the head of the entire operation, I decided personally to face up to the media attacks and rebut the false accusations about ICG’s malfeasance. Being reviled in TV and print interviews day after day was a harrowing experience, and it compounded my grief and sorrow in what I publicly described as “the worst week of my life.” Both the horrible event itself and the media attacks provided me with nightmares for a long time. Months later, when the inspectors made their report, there was little press interest. The tragedy was newsworthy. The fact that management was blameless was not.

Warren Buffett and Burlington Mills

One of my other major acquisitions at W.L. Ross & Co. was Burlington Mills – one of the leading textile mills in the United States. It and J.P. Stevens, another iconic mill, were suffering severely from foreign competition, mostly from Asia, as the apparel and other fabric-consuming industries moved abroad.

Burlington had grown to 8,000 employees since its founding in 1923, but went bankrupt in 2001 with $800 million in debts and a mountain of unfunded pension liabilities. Those facts caused it to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Its unsecured bonds then collapsed, and we bought quite a few. I became chairman of the unsecured creditors committee, and prepared to bid for the company. Because Burlington was an established name, and had a reputation for producing high-quality products, we believed we could buy it and return it to profitability.

But as it turned out, someone else had a similar theory of the case: Warren Buffett, perhaps the most brilliant investor of all time.

Buffett’s experience in the textile industry ran deep: he had built Berkshire Hathaway from the remnants of a failed textile company, and he had recently bought Fruit of the Loom, so he knew the value of what he was acquiring, just as I did. But where we diverged was on how we would bid for the company. Warren’s style is to decide on the value of something, bid it in cash, and if someone overbid, let it go. I and the other bondholders decided to outbid him using at par bonds in lieu of cash bonds that were trading at a steep discount.

In bankruptcy court, Warren tried to convince the judge that W.L. Ross & Co.’s bid should be disregarded, claiming cash was a more valuable currency than defaulted bonds. I was put up for cross-examination. When his lawyer, a famous bankruptcy practitioner from Jones Day named Bill Hayman, questioned me, his line of attack was to argue that surely cash was a better bid than our equity proposal.

My response was that the committee owned more than two-thirds of the bonds, and we preferred to take the equity. Since it was our investments that were at risk, not Buffett’s, the court should not impose an unwanted solution on us.

In the end, the judge agreed: “If the unsecured creditors prefer stock to cash, I will not overrule them.” We won.

Buffett is good-natured enough that this one victory did not preclude us from having a good relationship afterward. Sometime later, he and I were seated together at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. Someone wanted to photograph the two of us together. Warren said to me, “Let’s give them a scene of you and me fighting over my wallet!” We staged a grappling match, and the press got their picture. Afterward, he confided to me, “Wilbur, it really wasn’t worth fighting over. I only had one hundred dollars in it!”

Buffett’s living habits reflect his general good nature. Unlike most billionaires, Buffett lives in the same modest house he bought in Omaha decades earlier. His food tastes are also unchanged: He favors steak and Coca-Cola. Every year he auctions off for a charity a private lunch. The first one in 2000 went for $20,000. The most recent one sold for $19 million. I don’t know who has good enough clothes to wear to a $19 million lunch.

To return to Burlington, as part of our reorganization plan, we proposed a way we could buy the company just for the price of funding their pension liability. First, we would sell off the only truly profitable unit of their business, a leading carpet manufacturer (which we later did sell for 20-plus times earnings to Mohawk Industries for $352 million). That would raise enough capital to deleverage the company to the point where its only real liability was the pension fund. We then would exchange the defaulted publicly traded bonds for 100% of the equity.

The judge agreed with us, and that plan was put into motion. Soon, we merged Burlington with other assets we had acquired: Cone Mills, a leading denim producer, and Safety Components, a major auto seat-belt manufacturer. No one can accuse us of being terribly creative in naming the new company International Textile Group (“ITG”), following in the footsteps of International Steel Group and International Coal Group.

The next step in making ITG profitable involved internationalizing it.

We set up a joint venture in Mexico, allowing us to become a major producer there. We also started two joint ventures in China and in Vietnam. Sadly, the move to Vietnam proved to be one of the worst mistakes of my business career. As is common in Communist countries, including China, we were forced to rely on a state-run company as our business partner. State-run companies are dens of corruption and inefficiencies, and our Vietnamese “partner” made up the lost revenue by charging us seven times as much as they should have to run the business in Vietnam. The management was simply horrible. This was all my own fault – I should never have let my business be that dependent on a state-run company.

As a result, we lost every penny we put in there.

Even though the company worked out well we also underachieved on a bad bet we had made on one of its proprietary technologies. Burlington had a scientific operation called NanoTex, which imparted chemicals into fabrics in a way that made them impervious to moisture. When they showed me how a tie could be resistant to a ketchup stain, I was hooked. We spun the NanoTex operation out of Burlington, and backed it with money from my own fund and other venture investors.

At first, we convinced Brooks Brothers and other apparel retailers to buy NanoTex for its products, and things were going well. But two developments got in our way. First, another company, GoreTex, had developed a similar product that did as good a job, but was cheaper. This company had also figured out how to configure its formula so that it could be used on furniture and other fabrics. It would have taken serious money to compete with such a well-armed competitor, and that’s not the business I was interested in. Eventually, we sold the NanoTex brand to our investors and it faded away. The lesson is here that technology is a risky area: You can never be sure you have the best mousetrap. Or if you do, how long will that be true?

The Pros and Cons of Bankrupt Banks

I bought my first bank control position at age 30 – and it did not happen because of a crisis with the bank itself. The principal stockholder of the First New Haven National Bank in Connecticut also owned the major local department store. In 1977, downtown retailers in smaller cities were facing a crisis, as big suburban malls lured customers away from stores like the one in downtown New Haven.

My group bought his 15% stake in the bank to provide the liquidity he needed to keep the store going. The financial analytics all pointed to a good decision: The stock was trading at a big discount from book value and with a high dividend yield, which supported a margin loan for the purchase. We then brought in a more sophisticated CEO and the bank prospered.

A few years later we sold First New Haven to Shawmut Bank, and soon went to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston to approve the merger. In the lobby, a sign posted above the reception desk read: “The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston does not cash government checks.” Below that notice someone had written in black magic marker ink, “What do they know that we don’t know?”

Curiously, no one had removed the graffiti. Disdain for the Federal Reserve still runs deep in American politics today. The Fed is burdened with two mutually contradictory mandates: maximization of employment and controlling inflation toward a 2% per annum target. Easy monetary policy fosters the first and tighter monetary policy the second. As has been repeatedly demonstrated, the way this yin and yang is balanced has huge political and economic consequences, but the agency is at least theoretically non-partisan.

At Rothschild, my earliest bank advisory assignments were the Bank of New England and a defunct savings bank in Philadelphia. Later, I advised the Italian government on restructuring Banco di Napoli. Like many Italian banks, it was owned by a local “foundation” – one heavily influenced by the Neapolitan Mafia. When word got out on our involvement, a local Naples newspaper, perhaps as a warning, ran an editorial questioning why the Italian government had hired an American “thug” to advise on the bank.

Mafia bosses accusing me of being a thug – that was rich. Our investigation into the bank’s finances showed an abysmal loan portfolio and many loan documents conveniently missing from the files. It was thus very difficult to evaluate them. I recommended that the government extract the tainted loans and divide the good loans, deposits, and related branches into segments that would complement the generally uneconomically small branches of the many foreign and Italian banks operating there. We obtained enough premiums from those sales to offset much of the government’s losses embedded in the bad loans.

A far easier task was assisting the Mexican government on selling a small, failed bank to a major Spanish bank. When that went well, the government then invited Rothschild into a limited competition to advise them on the privatization of the Mexico City International Airport. Our presentation to the board went well until an old man sitting at the end of the table asked, “Señor Ross, how will you deal with the private aircraft fuel concession?” In other words, who got the contracts for refueling private planes, and how?

I responded, “These are best operated by specialists, so we would propose a separate competitive bid for this facility.”

Little did I know then that our answer cost us the assignment. Rumor was that the question had been planted by the drug cartels, who did not want outsiders to know that their planes were secretly buying enough fuel from the facility to run narcotics into the United States. Our competitor either guessed right or was tipped off, because his answer was, “We would leave that facility alone.”

Seeing Value in Ireland

In 2011, W.L. Ross & Co. had an opportunity to invest in the Bank of Ireland, our first European banking opportunity. At that time, the mortgage crisis was continuing to dominate that continent, and the Bank of Ireland was in dire straits. Larger private equity firms concluded that taking a piece of it in exchange for injecting liquidity and organizing a turnaround was too risky. Hence, there was no other bidder for the deal. But W.L. Ross went in at the invitation of my friend Prem Watsa, known as the Warren Buffett of Canada. Our decision was, as always, based on rigorous analysis. Most firms were wary of Ireland because they believed it was too dependent on friendly corporate tax rates for prosperity. They also regarded the Irish economy as similar to those of sclerotic Western European nations.

They had not done enough homework! Upon further examination, the Irish economy had many factors besides tax rates that augured a brighter economic future than other European countries could hope to enjoy. Ireland had excellent transportation and telecom facilities, and a young, well-educated, and diligent workforce. U.S. companies, mainly tech and pharmaceutical companies, had located production facilities there and often used Ireland as their base for European operations. (In fact, the little blue pills that give middle-aged men such pleasure are made in Ireland.)

Also important were the government’s extreme belt-tightening during the crisis and its fully funded national retirement system. Additionally, Ireland had the least restrictive of any European employment regulations. Laws making it very hard to release workers actually reduce employment, because employers are loath to hire workers whom they can’t let go – a fact overlooked by EU and U.S. legislators. Ireland didn’t have that problem. The fact that English was the spoken language was another plus. It was essential to understanding the economy, because when you buy the largest bank in a country you are really buying a warrant on that economy.

Upon sealing the deal, we made a few rapid moves. We took over part of the government’s rights to subscribe to a third round of new capital. And, at our insistence, an existing Bank of Ireland executive, a South African named Richie Boucher, became our CEO. Two years later, the bank had been restored to health. Things went so well that I sold my stake in 2014 at a nearly 300% return.

Part of the strategy for the bank’s recovery involved me going on TV to repeatedly proclaim with confidence my belief in Ireland’s “V-shaped recovery,” and my conviction that the bank’s problems were behind it. That helped convince other investors that Ireland was a place to be in the long run. A few years later, the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) of Ireland, Enda Kenny, went into great detail about my role in the bank’s recovery in a speech to the American Ireland Fund at the Breakers resort in Palm Beach. The Irish press also repeatedly referred to me as “the man who saved Ireland.”

It was, of course, hyperbole, but it did boost my standing with my Irish-American wife.

The successes I had at W.L. Ross & Co. brought my career to a new level. It is certain that I benefited from a network of personal and professional contacts who were as generous with their advice and invitations as they were skilled in financial dealmaking. But in truth, the victories were attributable to a continuation of habits adopted early in my career. A dedication to preparation, focus, and discipline – executing your strategy for a successful outcome despite any distraction or adversity – has made all the difference.

Excerpted from Risks and Returns: Creating Success in Business and Life, by Wilbur Ross (Regnery Publishing, 2024), with permission from the author

Let us know what you are reading this summer by sharing your current book list to [email protected].

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD