Betting on perfection is a fool’s errand in any environment. It’s particularly risky today as the economy teeters on the edge of recession and a looming debt crisis. Fortunately, the bubble in AI and tech stocks is setting up a tremendous opportunity elsewhere.

If You Overpay, Are You Really “Winning”?

If you’re new here:

Welcome! You’re reading “Something You Don’t Know,” Porter’s complimentary e-letter. It reveals a hidden market story, or dissects a largely misunderstood element of investing, every other Friday, at no charge. You can see our archive of earlier issues at this link.

NFL New Orleans Saints head coach Mike Ditka was obsessed with 22-year-old prospect Ricky Williams.

A 5’10” running back coming out of the University of Texas, Ricky wasn’t unlike many of the other extraordinarily gifted athletes who make it into pro football. Except that he had a bad habit of getting injured… and showed up for his first NFL tryouts 20 pounds overweight – and refused to participate in workouts.

That didn’t deter coach Ditka, though. He saw greatness in young Ricky, who reminded him of Walter “Sweetness” Payton, an iconic Chicago Bears player he’d coached a decade earlier. And whether it was nostalgia, a belief that Ricky really was the second coming of “Sweetness,” or a cocktail of the two, Ditka wanted Ricky, bad.

So he traded every one of his draft picks for that year in order to get Ricky Williams on the Saints.

Each NFL team gets to pick one fresh-out-of-college player per round in the seven-round NFL draft. In the now-infamous 1999 draft, Ditka traded away six of his picks – plus two picks in the upcoming 2000 draft – to move up in the draft in order to lock down Ricky Williams.

The 8-for-1 gamble made headlines, including an epically cringe-worthy ESPN photoshoot that featured Ditka and Williams in wedding attire with the caption, “For Better or for Worse.”

But – you might have seen this coming – Ricky Williams wasn’t all that Ditka had hoped.

In his first NFL season, Ricky suffered a string of injuries and the Saints limped through their second-worst season in franchise history, ending at 3 wins and 13 losses. At the end of the season, Mike Ditka was fired.

Ricky wound up spending three seasons with the Saints, before he was traded to the Miami Dolphins in 2002. His solid but unremarkable 11-year NFL career was punctuated by injuries, substance abuse, and breaks for rehab and suspensions. He definitely didn’t live up to Ditka’s expectations… nor was he worth the NFL equivalent of a king’s ransom that the Saints paid.

Ditka – who as recently as 2010 said that he’d “absolutely” make the same trade again – fell prey to a phenomenon known as “the winner’s curse.” Simply put, the person who “wins” the auction almost always overpays.

The “winner’s curse” crops up anytime people get (overly) excited about bidding on something: Used cars, sports drafts, oil fields, a rival company. It was first documented in 1971 by three petroleum engineers – Edward Capen, Robert Clapp, and William Campbell – who noticed that oil companies kept suffering disappointing returns on their investment after bidding on the Outer Continental Shelf oil lease auctions.

Capen, Clapp, and Campbell concluded that “bidders did not have sufficient knowledge of the laws of probability to make rational informed decisions, and instead were being swayed by the bids of other oil companies.” Essentially, thanks to the madness of crowds, buyers who let their emotions get in the way often end up overbidding… and overpaying.

As Mike Ditka discovered, the “winner’s curse” may end up costing far more than the winner anticipates.

And – though it’s not an auction, per se – we see a similar curse any time we examine a super-hyped market bubble. Excited buyers overpay for “hot” stocks… but when valuations come back down to earth, the romance inevitably ends.

Take the 1999-2000 dot-com bubble, for instance…

The Price You Pay Matters

In 2000, Sun Microsystems was one of the most valuable companies in the U.S.

Like other darlings of the dot-com era, Sun shares had soared over the preceding decade, from a split-adjusted price of roughly $1 in 1995, to a high of $64 in early 2000. By then, the company was trading at a price-to-sales (P/S) multiple of more than 10x.

The P/S ratio is one of the simplest measures of valuation. While the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio indicates how much investors are paying per dollar of a company’s earnings (profits), the P/S indicates how much they’re paying per dollar of sales (revenue).

The P/S ratio is a useful tool for valuing early-stage or high-growth companies that don’t have earnings. It also tends to be more useful for identifying overvalued rather than undervalued companies, as a company with a low P/S may still be richly valued depending on the quality of its business (capital efficiency, margins, etc.).

Average P/S ratios can vary by industry, but anything over 10x is considered extremely overvalued by even the most generous standards.

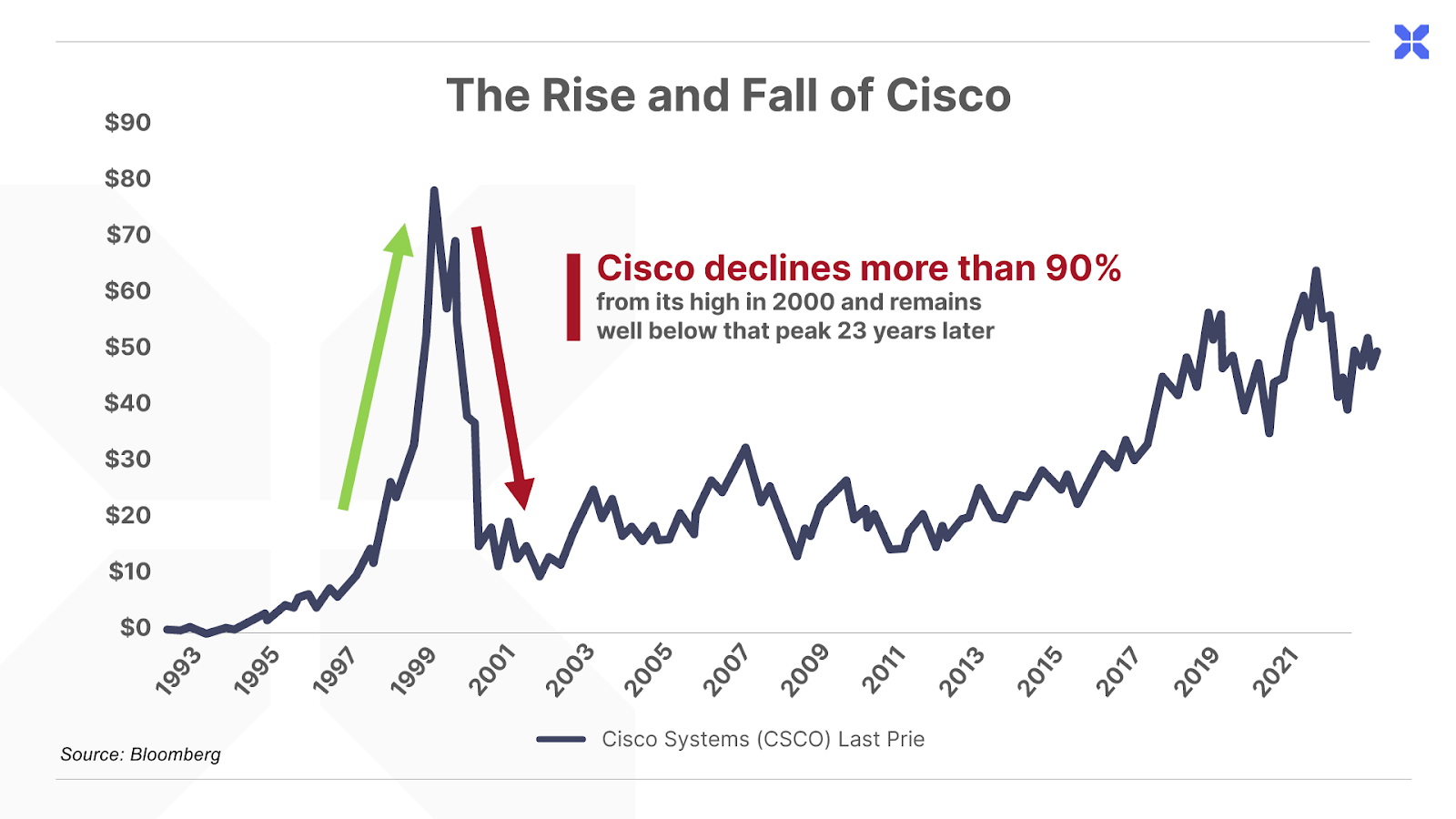

Sun wasn’t alone… At the peak of the Internet frenzy, more than three dozen S&P 500 companies achieved this feat, including such notables as Intel (16x), Qualcomm (25x), Microsoft (26x), Oracle (44x), and Cisco Systems (60x).

Of course, as we now know, the good times were fleeting. Over the next few years, the broad market plunged more than 50%. Blue-chip darlings like Sun lost 90%, or more, of their value. Lots of one-time hot stocks vanished altogether.

The tech bust decimated the savings of an entire generation of overeager investors… who got too excited, paid too much, and experienced the stock market version of the “winner’s curse.”

But it wasn’t just the depth of the decline in these stocks that was so painful. It was also the duration. Investors who owned even the (ostensibly) best companies in this bunch could easily have been underwater for a decade or more.

For example, Microsoft fell “only” 75% from peak to trough – far less than most other blue-chip tech firms. But its shares didn’t surpass their dot-com bubble peak until late 2016 – nearly 17 years later.

Some shares are still trading well below those 2000 highs today, including Intel (still 59% below dot-com peak) and Cisco (39% below dot-com peak).

(Sun Microsystems was no exception. It was trading more than 90% below its peak 2000 share price when it was acquired by Oracle in 2009.)

As Sun CEO Scott McNealy pointed out in a now-classic Businessweek interview in April 2002, what happened shouldn’t have been a big surprise…

“Two years ago, we were selling at 10 times revenues when we were at $64. At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends.

“That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. That assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal. And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10 years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate.

“Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes. What were you thinking?

McNealy’s admission reflects one of the fundamental truths of investing: The price you pay matters. Even the best businesses (or running backs) are likely to be terrible investments if you pay too much for them.

Many dot-com era investors learned this lesson the hard way. And unfortunately, a new generation of investors appears destined to repeat those mistakes today.

Tech Bubble 2.0

As paid-up readers of The Big Secret on Wall Street know, there’s a new frenzy in the tech world that harkens back to the halcyon days of earlier bubbles. As we wrote on May 26:

“Today, a new technology (AI) promises to convert the abundance of microprocessing power and computer networks into useful intelligence, the demand for which is widely believed to be unlimited.

Like all manias, faith in the unbridled future is enough for investors to plunk down huge sums of capital.

Consider the case of Mobius AI – a new startup founded earlier this year by four former Google researchers. According to a recent New York Times article, the founders “weren’t sure what their product might be — just that it would involve AI technology that could generate its own photos and videos.”

Despite having little more than four employees and an AI dream, it was enough for two of the top U.S. venture capital (VC) firms, Andreessen Horowitz and Index Ventures, to fund the business at a $100 million valuation. Similar deals have been struck for other brand new start-up companies. More than $50 billion was invested into AI startups in 2022.”

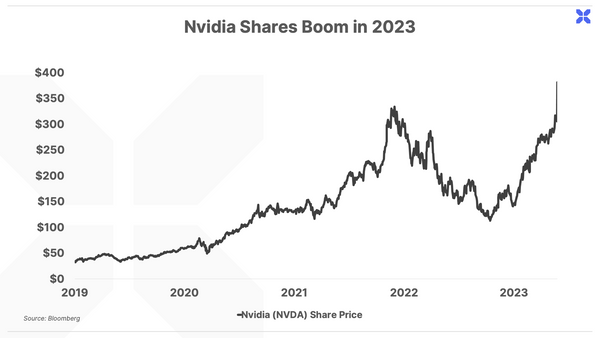

Even greater sums are being wagered in the public markets, where exuberant investors have been bidding up the shares of a handful of AI-related companies to dot-com-era extremes.

The market valuation of chipmaker Nvidia (NVDA), fuelled by AI hype, has risen from $350 billion in January, to around $1 trillion today.

Today Nvidia shares trade in excess of 37 times sales. That’s on par with the most extreme blue-chip valuations of the internet bubble – and nearly four times richer than that which prompted McNealy’s comments more than two decades ago.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that the AI bubble won’t continue to inflate – or that Nvidia shares can’t soar even higher as it does. Manias can go on longer (and end more quickly) than almost anyone believes possible.

However, as we recently noted to Big Secret readers, Nvidia is priced for “perfection.” It must continue to grow and execute flawlessly to simply maintain – for now – its current valuation… anything less is likely to lead to significant losses for today’s shareholders (who are likely to suffer hefty losses in coming months in any case).

It’s a similar story for a number of other AI-related names, including fellow blue-chips Microsoft and Adobe (each trading at roughly 11x sales), as well as other tech darlings like Atlassian (14x), Palantir (16x), C3.ai (17x), and Snowflake (23x).

Betting on perfection is a fool’s errand in any environment. It’s particularly risky today as the economy teeters on the edge of recession and a looming debt crisis.

Ultimately, as in the aftermath of the dot-com boom – and countless other manias before it – most AI investors are likely to be left holding massive losses in the end.

Fortunately, the bubble in tech stocks is setting up a tremendous opportunity elsewhere.

Overworked and Underpaid

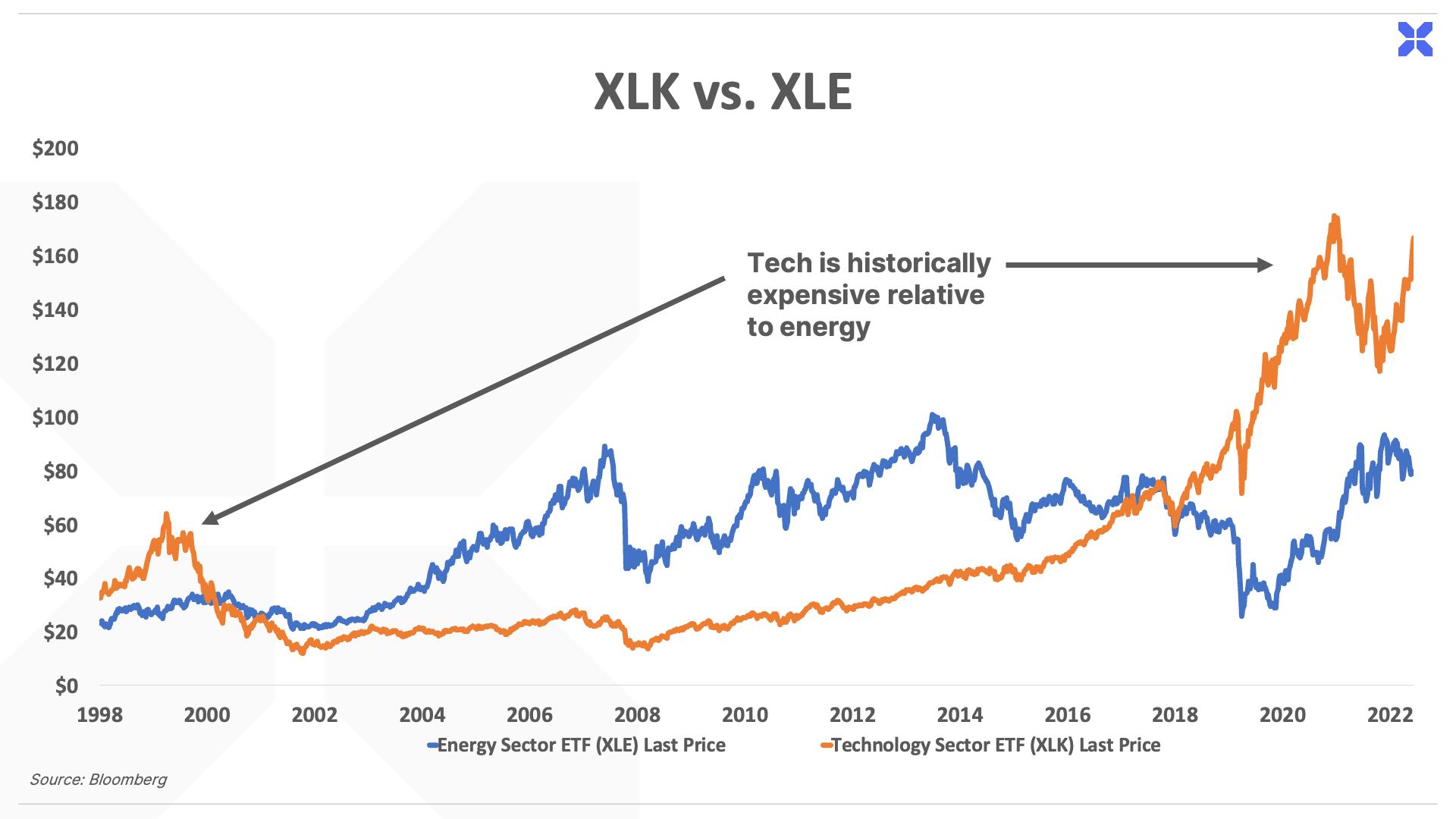

As investors rushed into technology stocks in the late 1990s, they ignored other sectors. By the peak of the bubble in the early 2000s, so-called “old economy” sectors – energy in particular – had fallen to historically cheap valuations that were the converse of the overvaluations in tech.

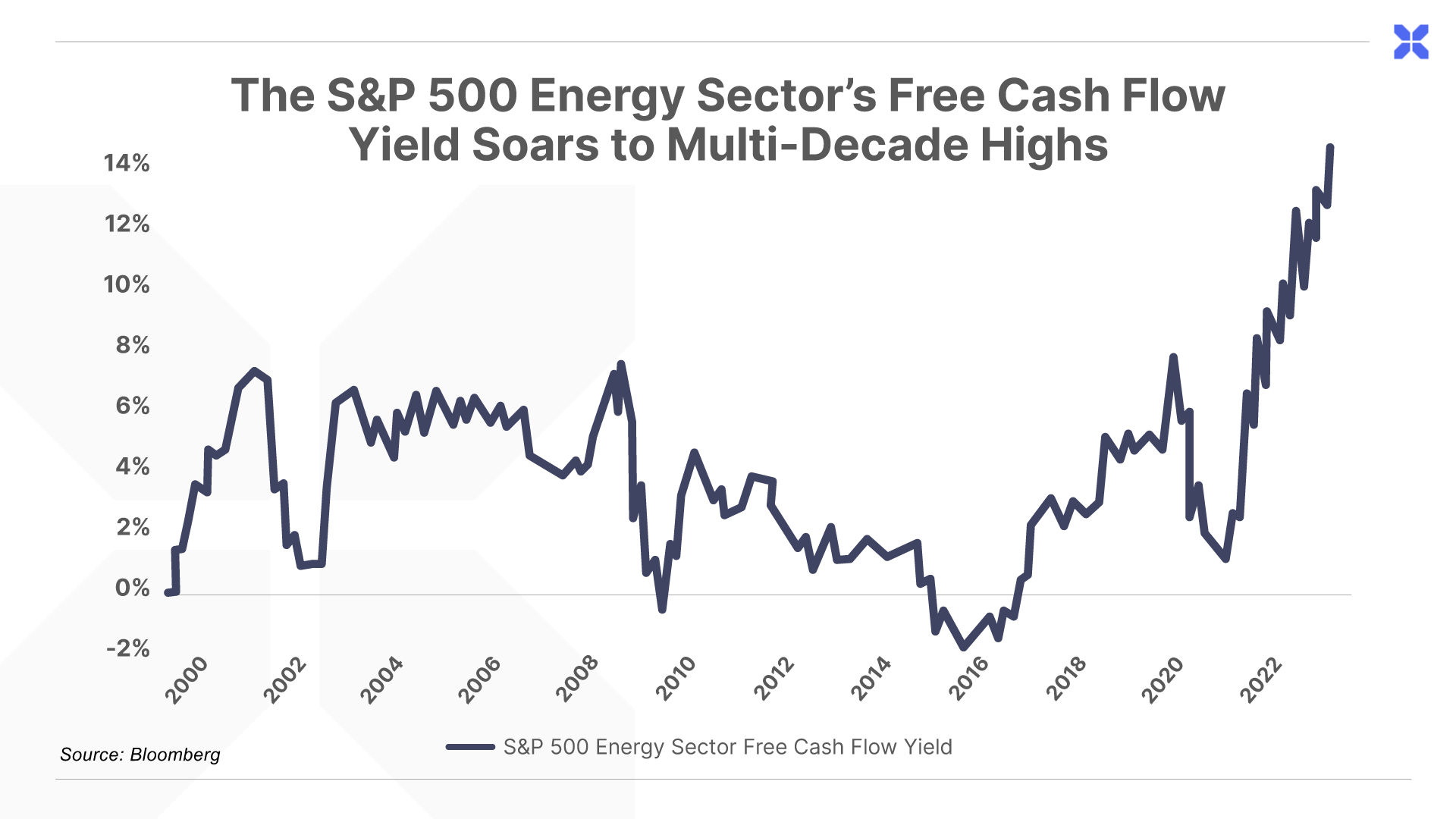

At the peak of the frenzy, the technology sector as a whole was trading at a P/S of 7 and a P/E near 60. Yet, as the bubble burst, the energy sector was trading at a P/S near 1, and an average P/E well below 20. The energy sector also offered a peak free cash flow (FCF) yield above 7%.

FCF yield is among the most conservative ways to value a company.

FCF is simply the cash that’s left over after a company pays all its operating expenses and makes any necessary long-term investments (capital expenditures). It’s the cash a company actually has on hand to return to shareholders through dividends or share buybacks, which makes it a far more reliable metric than earnings (which can easily be manipulated).

The FCF yield is similar to a company’s dividend yield – only instead of using the money the company pays out in dividends (which may be more or less than it actually has on hand), it counts all of the cash it has available to pay out to shareholders.

All things equal, the higher a company’s FCF yield, the cheaper the shares are – with yields above 5%-7% considered particularly attractive.

The early 2000s divergence between the energy and technology sectors ultimately set the stage for a massive “mean reversion” that saw energy stocks dramatically outperform tech stocks – and the broad market – for most of the following decade.

The following chart of the Technology Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLK) versus the Energy Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLE) puts this performance in perspective.

You’ll also notice a similar divergence has appeared over the past several years, as technology again outperformed energy.

This divergence briefly began to close in late 2021 and 2022 as the bear market weighed heavily on tech stocks. However, this year’s AI frenzy has seen the gap widen dramatically again, setting the stage for significant energy outperformance in the years ahead.

Energy Stocks Are A Great Bargain No Matter What

Yet, the energy sector isn’t just inexpensive relative to tech. It’s incredibly cheap on an absolute basis as well.

In fact, as the chart below shows, energy stocks currently offer a FCF yield of more than 13% – nearly double their yield in the early 2000s.

In other words, energy stocks are arguably a significantly better value today than they were back then.

The recent weakness in energy stocks has occurred alongside a roughly 20% decline in oil prices, from just under $90 per barrel last fall to around $70 today. Yet despite this price weakness – and rising fears that an impending recession could push prices even lower – the fundamental outlook for oil is bullish.

The Big Oil Squeeze

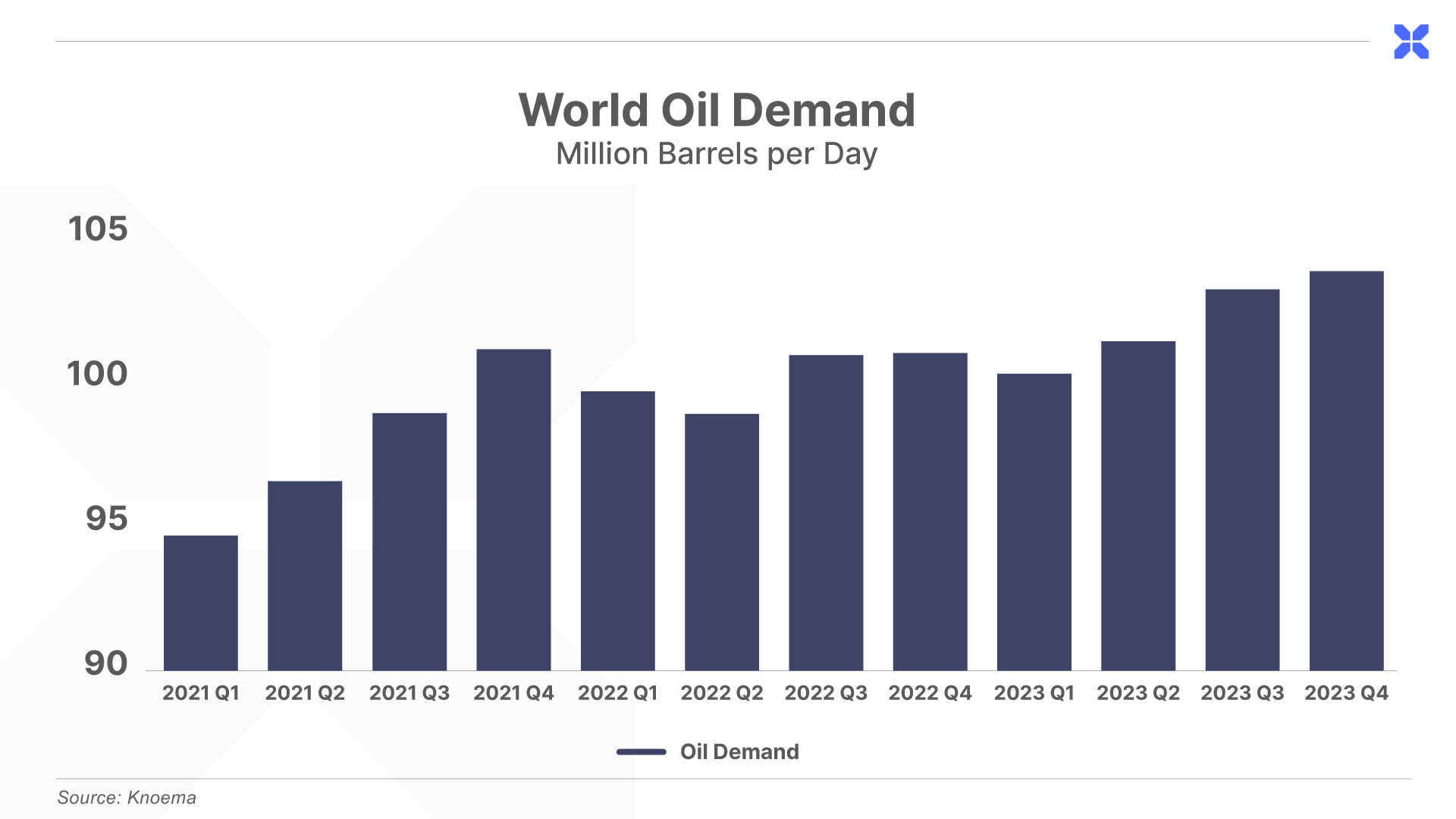

First, global oil demand continues to rebound from its COVID-19 lows, with China leading the way.

After months of fits and starts, China’s economy has finally reopened in full following the end of its draconian “zero-COVID” policies late last year. And though the reopening has proceeded slower than initially expected, official data suggest Chinese oil demand rose to a new all-time record of more than 16 million barrels per day (bpd) in April.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects this trend to continue. It now forecasts global oil demand will rise to a new record of 101.9 million bpd by the end of 2023, representing a year-over-year increase of roughly 2 million bpd. (That’s even despite lower oil demand in the U.S. and Europe due to slowing economic growth in the second half of the year.)

And while demand has been steadily rising, global oil supply has continued to contract…

U.S. shale oil production – which accounted for roughly 90% of the supply growth over the past decade – has largely flatlined as rising costs and a punitive regulatory environment have disincentivized new investment.

Meanwhile, the OPEC+ oil cartel has announced production cuts of 1.66 million bpd this year – and, so far, it appears they’re following through on their promises.

Altogether, the IEA estimates these trends could cause global oil supply to fall by at least 400,000 bpd through December.

This implies the world is likely to shift from a small oil supply surplus in 2022 to a significant supply deficit of 1.5 million bpd to as much as 2.6 million bpd by the end of this year…. creating an additional strong tailwind for oil prices.

Notably, outside of the COVID lockdowns, recessions historically haven’t moved the needle much on oil demand.

For example, during the 2008-2009 recession – which coincided with the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression – oil demand fell by just 1.6%. A similar slowdown today would represent a decline of roughly 1.6 million bpd, suggesting even a severe recession may not be enough to push the oil market back into a surplus again.

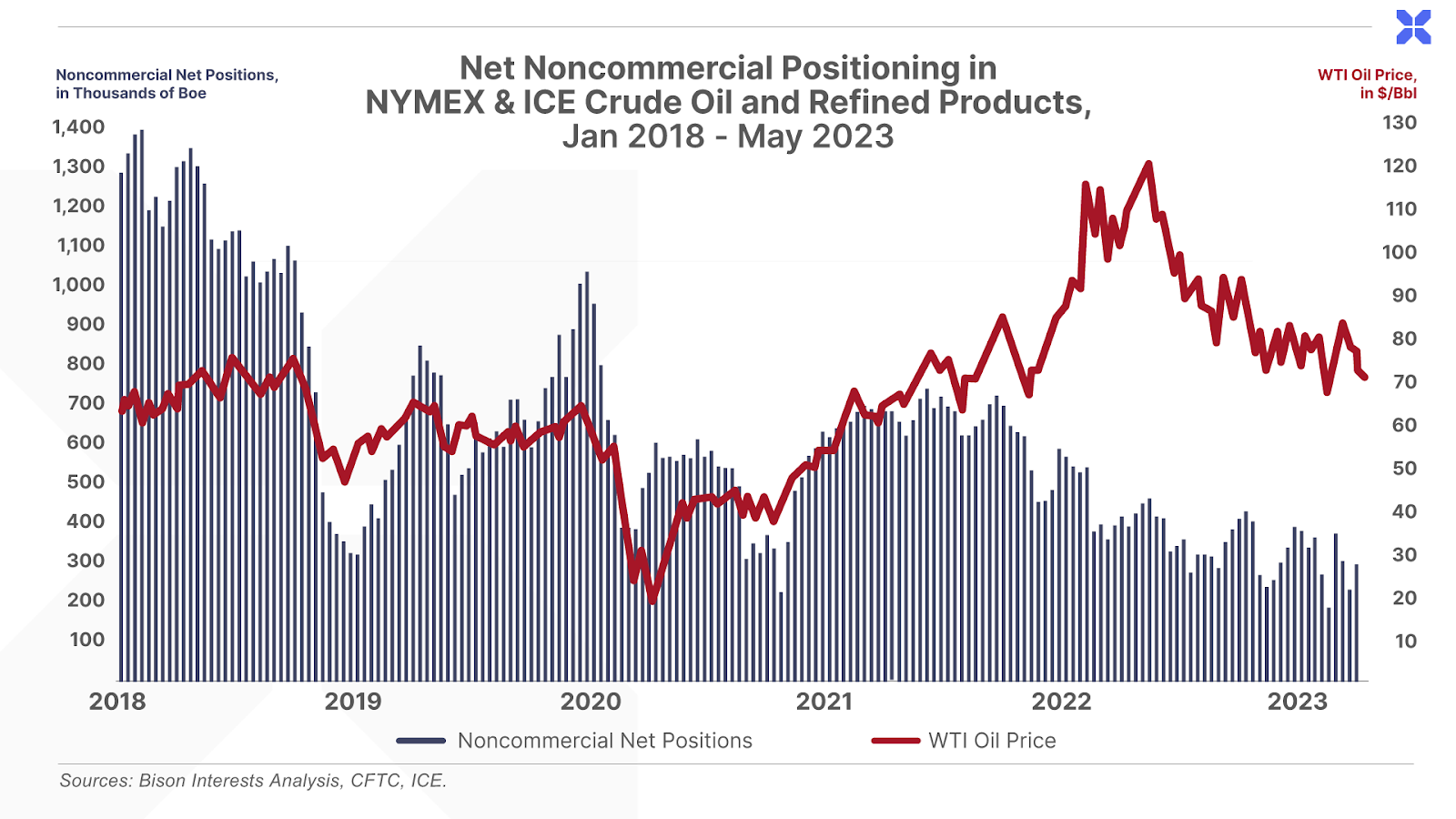

Yet, remarkably – despite low supply and high demand for oil – institutional investors are ignoring energy right now.

Right now, “non-commercial” firms – which include hedge funds and other investors that tend to speculate on oil prices via the futures markets – currently hold one of their smallest net long positions in years. By this measure, investors are actually less bullish on oil than they were at the depths of the COVID lows.

In sum, investors willing to look past the AI hype today have a rare chance to buy cash-gushing businesses in a civilization-essential sector with positive fundamentals at some of their cheapest valuations in decades.

And, as a bonus, they’ll completely dodge the “curse” of overpaying for bid-up bubble stocks.

If you’re interested in this opportunity, be sure to read the latest issue of The Big Secret on Wall Street, where we reviewed two of our favorite investments in the energy sector.

These companies are currently offering best-in-class free cash flow yields of 15% and 20%, respectively, along with tremendous upside potential in the years ahead.

Click here to learn more.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

P.S. If you’d like to learn more about the Porter & Co. team – all of whom are real humans, and many of whom have Twitter accounts – you can get acquainted with us here – or email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected].