Even Dictators Can’t Lead Alone

The Ruthless Art Of Political Survival

| Editor’s Note: Porter & Co. is following a lighter publishing schedule in August, and we continue to monitor all of our portfolios – and will send updates and buy and sell alerts on our open positions when needed for all services. This August, we’re producing a special series called “What We’re Reading.” Each Friday during the month, we are sending Big Secret readers a literary excerpt or investing insight that you won’t see anywhere else. Members of the Porter & Co. team are sharing an excerpt from their personal summer reading – books that they found instructive, or ones that they just plain enjoyed. We hope you’ll enjoy them too. Last week, Distressed Investing analyst Marty Fridson served up an exclusive advance look at former Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ upcoming memoir Risks and Returns, where the nicknamed “King of Bankruptcy” shared negotiating insights from his decades on Wall Street. We’re continuing this month’s program with “what Kim’s reading”… This week, Porter & Co. CEO and publisher Kim Iskyan provides an excerpt of The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics, by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith… Kim also shares his insights into this work about leadership and power in his brief introduction below. In addition to hosting this issue on our website, we also make it available as a downloadable PDF. Click here to download the full issue. |

I worked in political-risk consulting for several years, I studied international relations in college, and I have a graduate degree in history. But I could have saved myself a lot of trouble – and been way ahead of everyone else from the get-go – if I’d been able to read The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics, by two savvy political scientists, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith. (I would have needed a time machine, as I finished grad school years before the authors tapped out this masterpiece… but anyway.)

The premise of The Dictator’s Handbook is that all politics – and, more broadly, all organizations, from school boards to Fortune 500 companies to the local dry cleaner – is a function of individual motivations and desires and ambitions. Institutions don’t act with single-minded objectives or goals… They’re a bubbling cauldron of individual agendas that may or may not overlap with that of the institution. It’s a simple idea… but far more nuanced in practice than you might think. De Mesquita and Smith pack the book with vivid stories and examples. And – especially today – you can see them yourself in Technicolor. This is an applied poli-sci degree in a nutshell… and well worth your time.

In the excerpt below, de Mesquita and Smith explain how France’s Louis XIV consolidated power in the 17th century… outline their fascinating – and startlingly applicable – model of political power (the “nominal selectorate,” the “real selectorate,” and the “winning coalition”)… chronicle why Che Guevara was a dead man well before he was, well, dead… lay out their “five basic rules leaders can use to succeed in any system”… and profile the politics of software giant Hewlett-Packard and its former CEO (and one-time Republican presidential candidate) Carly Fiorina.

I hope you enjoy this extract from The Dictator’s Handbook, which includes much of Chapter 1, “The Rules Of Politics,” and a portion of Chapter 3, “Staying In Power.” – Kim Iskyan, CEO and Publisher

From Chapter 1: The Rules of Politics

The Rules Of Power

The logic of politics is not complex. In fact, it is surprisingly easy to grasp most of what goes on in the political world as long as we are ready to adjust our thinking ever so modestly. To understand politics properly, we must modify one assumption in particular: we must stop thinking that leaders can lead unilaterally.

No leader is monolithic. If we are to make any sense of how power works, we must stop thinking that North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un can do whatever he wants. We must stop believing that Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin or Genghis Khan or anyone else is in sole control of their nation. We must give up the notion that Enron’s Kenneth Lay or British Petroleum’s Tony Hayward knew about everything that was going on in their companies or that they could have made all the big decisions. All of these notions are flat-out wrong because no emperor, no king, no sheik, no tyrant, no chief executive officer, no family head, no leader whatsoever can govern alone.

Consider France’s Louis XIV (1638-1715). Known as the Sun King, Louis reigned as monarch for over 70 years, presiding over the expansion of France and the creation of the modern political state. Under Louis (shown below), France became the dominant power in continental Europe and a major competitor in the colonization of the Americas. He and his inner circle invented a code of law that helped shape the Napoleonic code and that forms the basis of French law to this day. He modernized the military, forming a professional standing army that became a role model for the rest of Europe and, indeed, the world. He was certainly one of the pre-eminent rulers of his or any time. But he didn’t do it alone.

The word monarchy may mean “rule by one,” but such rule does not, has not, and cannot exist. Louis is famously (and probably falsely) thought to have proclaimed, “L’état, c’est moi” (The state, it is me). This declaration is often used to describe political life for supposedly absolute monarchs like Louis, likewise for tyrannical dictators. The declaration of absolutism, however, is never true. No leader, no matter how august or how revered, no matter how cruel or vindictive, ever stands alone. Indeed, Louis XIV, ostensibly an absolute monarch, is a wonderful example of just how false this idea of monolithic leadership is.

After the death of his father, Louis XIII (1601-1643), Louis rose to the throne when he was four years old. During the early years actual power resided in the hands of a regent – his mother. Her inner circle helped themselves to France’s wealth, stripping the cupboard bare. By the time Louis assumed actual control over the government in 1661, at the age of 23, the state over which he reigned was nearly bankrupt.

While most of us think of a state’s bankruptcy as a financial crisis, looking through the prism of political survival makes evident that it really amounts to a political crisis. When debt exceeds the ability to pay, the problem for a leader is not so much that good public works must be cut back but rather that the incumbent doesn’t have the resources necessary to purchase political loyalty from key backers. Bad economic times in a democracy mean too little money to fund pork-barrel projects that buy political popularity. For kleptocrats, they mean passing up vast sums of money and maybe even watching their secret bank accounts dwindle, along with the loyalty of their underpaid henchmen.

The prospect of bankruptcy put Louis’s hold on power at risk because the old-guard aristocrats, including the generals and officers of the army, saw their sources of money and privilege drying up. Circumstances were ripe for these politically crucial but fickle friends to seek someone better able to ensure their wealth and prestige. Faced with such a danger, Louis needed to make changes or else risk losing his monarchy.

Louis’s specific circumstances called for altering the group of people who had the possibility of becoming members of his inner circle – that is, the group whose support guaranteed his continued dignity as king. He moved quickly to expand the opportunities (and for a few, the actual power) of new aristocrats, called the noblesse de robe. Together with his chancellor, Michel Le Tellier, he acted to create a professional, relatively meretricious army. In a radical departure from the practice observed by just about all of his neighboring monarchs, Louis opened the doors to officer ranks – even at the highest levels – to make room for many more than the traditional old-guard military aristocrats, the noblesse d’épée. In so doing, Louis was converting his army into a more accessible, politically and militarily competitive organization.

Meanwhile, Louis had to do something about the old aristocracy. He was deeply aware of their earlier disloyalty as instigators and backers of the anti-monarchy Fronde (a mix of revolution and civil war) at the time of his regency. To neutralize the old aristocracy’s potential threat, he attached them to his court – literally, compelling them to be physically present in Versailles much of the time. This meant that their prospects of income from the crown depended on how well favored they were by the king. And that, of course, depended on how well they served him.

By elevating so many newcomers, Louis created a new class of people who were beholden to him. In the process, he centralized his own authority more fully and enhanced his ability to enforce his views at the cost of many of the court’s old aristocrats. Thus he erected a system of “absolute” control whose success depended on the loyalty of the military and the new aristocrats, and on tying the hands of the old aristocrats so that his welfare translated directly into their welfare.

The French populace in general did not figure much into Louis’s calculations of who needed to be paid off – they did not represent an imminent threat to him. Even so, it’s clear that his absolutism was not absolute at all. He needed supporters, and he understood how to maintain their loyalty. They would be loyal to him only so long as being loyal was more profitable for them than supporting someone else.

Louis’s strategy was to replace the “winning coalition” of essential supporters that he inherited with people he could more readily count on. In place of the old guard, he brought up and into the inner circle members of the noblesse de robe and even, in the bureaucracy and especially in the military, some commoners. By expanding the pool of people who could be in the inner circle, he made political survival for those already in that role more competitive. Those who were privileged to be in his winning coalition knew that with the enlarged pool of candidates for such positions, any one of them could easily be replaced if they did not prove sufficiently trustworthy and loyal to the king. That, in turn, meant they could lose their opportunity for wealth, power, and privilege. Few were foolish enough to take such a risk.

Like all leaders, Louis forged a symbiotic relationship with his inner circle. He could not hope to thrive in power without their help, and they could not hope to reap the benefits of their positions without remaining loyal to him. Loyal they were. Louis XIV survived in office for seventy-two years until he died quietly of old age in 1715.

Louis XIV’s experience exemplifies the most fundamental fact of political life. No one rules alone. No one has absolute authority. All that varies is how many backs have to be scratched and how big the supply of backs available for scratching is.

Three Political Dimensions

For leaders, the political landscape can be broken down into three groups of people: the nominal selectorate, the real selectorate, and the winning coalition.

The nominal selectorate includes every person who has at least some legal say in choosing their leader. In the United States it is everyone eligible to vote, meaning all citizens aged eighteen and over. Of course, as every citizen of the United States must realize, the right to vote is important, but at the end of the day no individual voter has a lot of say over who leads the country. Members of the nominal selectorate in a universal-franchise democracy have a toe in the political door, but not much more. In that specific way, the nominal selectorate in the United States or Britain or France doesn’t have much more power than its counterparts, the “voters,” in the old Soviet Union. There, too, all adult citizens had the right to vote, although their choice was generally to say yes or no to the candidates chosen by the Communist Party rather than to pick among candidates. Still, every adult citizen of the Soviet Union, where voting was mandatory, was a member of the nominal selectorate.

The second stratum of politics consists of the real selectorate. This is the group that actually chooses the leader. In today’s China (as in the old Soviet Union), it consists of all voting members of the Communist Party; in Saudi Arabia’s monarchy it is the senior members of the royal family; in Great Britain, the voters backing members of Parliament from the majority party.

The most important of these groups is the third, the subset of the real selectorate that makes up the winning coalition. These are the people whose support is essential if a leader is to survive in office. In the USSR the winning coalition consisted of a small group of people inside the Communist Party who chose candidates and who controlled policy. Their support was essential to keep the commissars and general secretary in power. These were the folks with the power to overthrow their boss – and he knew it. In the United States, the winning coalition for the presidency is vastly larger than in the old Soviet system, but because of the peculiarities of the Electoral College, it is nowhere near a majority or even a plurality of voters. For Louis XIV, the winning coalition was a handful of members of the court, military officers, and senior civil servants without whom a rival could have replaced the king.

Fundamentally, the nominal selectorate is the pool of potential support for a leader; the real selectorate includes those whose support is truly influential; and the winning coalition extends only to those essential supporters without whom the leader would be finished. A simple way to think of these groups is as interchangeables, influentials, and essentials.

In the United States, the voters are the nominal selectorate – interchangeables. As for the real selectorate – influentials – the electors of the Electoral College really choose the president (just as the party faithful picked the general secretary back in the USSR), but the electors nowadays are normatively bound to vote the way their state’s voters voted, so they don’t really have much independent clout in practice. That is true, however, only if state legislatures do not change the rules for selection of their electors. If they do – in keeping with the U.S. Constitution, by the way – then the winning coalition could be much, much smaller. In the United States, the nominal selectorate and real selectorate so far have been pretty closely aligned.

This is why, even though you’re only one among many voters, interchangeable with others, you still feel like your vote is influential – that it counts and is counted. The winning coalition – essentials – in the United States is the smallest bunch of voters, properly distributed among the states, whose support for a candidate translates into a presidential win in the Electoral College. The winning candidate may, of course, garner many more votes than the essential minimum they need to win the presidency. Those extra voters plus the essentials make up the support coalition. The support coalition must not be confused with the winning coalition. As we will see, essentials get goodies that the excess supporters may not receive. It is easy to confuse the support coalition and the essential, winning coalition in a democracy. Their differences are much more obvious when the essential group is very small.

With the distinction between essentials and the support coalition firmly in mind, we can see that while the winning coalition (essentials) is a pretty big fraction of the nominal selectorate (interchangeables) in the United States, it doesn’t have to be even close to a majority of the U.S. population. In fact, given the federal structure of American elections, it’s possible to control the executive and legislative branches of government with as little as about one-fifth of the vote, if the votes are really efficiently placed. (Abraham Lincoln and Donald Trump were masters at just such voter efficiency.) Indeed, the absolute popular vote margin tells us almost nothing in a great many places, including, distressingly, the United States.

Still, it is worth observing that the United States has one of the world’s biggest winning coalitions both in absolute numbers and, most importantly, as a proportion of the electorate. But it is not the biggest. Britain’s parliamentary structure requires the prime minister to have the support of a little over 25% of the electorate in two-party elections to Parliament. That is, the prime minister generally needs at least half the members of Parliament to be from her party and for each of them to win half the vote (plus one) in each two-party parliamentary race: half of half of the voters, or one-quarter. France’s runoff system can be even more demanding. Election requires that a candidate win a majority in the final, two candidate runoff, but, of course, to make the runoff it is only necessary to have one more vote than the third-place finisher. If, say, 10 candidates ran, then getting into the runoff might require few votes indeed!

Looking elsewhere we see that there can be a vast range in the size of the nominal selectorate, the real selectorate, and the winning coalition. Some places, like North Korea, have a mass nominal selectorate in which everyone gets to vote – it’s a joke, of course – a tiny real selectorate that actually picks the leader, and a winning coalition that surely is no more than maybe a couple of hundred people (if that) and without whom even North Korea’s first leader, Kim Il-Sung (pictured in Kim Il-Sung Square in Pyongyang above), could have been reduced to ashes. Other nations, like Saudi Arabia, have tiny nominal and real selectorates, made up of the royal family and a few crucial merchants and religious leaders. The Saudi winning coalition is perhaps even smaller than North Korea’s.

Virtues Of 3D Politics

You may find it hard to believe that just these three dimensions govern all of the varied systems of leadership in the world. After all, our experience tends to confirm that on one end of the political spectrum we have autocrats and tyrants – horrible, selfish thugs who occasionally stray into psychopathology. On the other end, we have democrats – elected representatives, presidents, and prime ministers who we like to think are the benevolent guardians of freedom. Leaders from these two worlds, we assure ourselves, must be worlds apart!

It’s a convenient fiction but a fiction nonetheless. Governments do not differ in kind. They differ along the dimensions of their selectorates and winning coalitions. These dimensions limit or liberate what leaders can and should do to keep their jobs. How limited or liberated a leader is depends on how selectorates and winning coalitions interact.

No question, it is tough to break the habit of talking about democracies and dictatorships as if either of these terms is sufficient to convey the differences across regimes, even though no two “democracies” are alike and neither are any two “dictatorships.” In fact, it is so hard to break that habit that we will continue to use these terms much of the time throughout this book – but it is important to emphasize that the term dictatorship really means a government based on a particularly small number of essentials drawn from a very large group of interchangeables and, usually, a relatively small batch of influentials.

On the other hand, if we talk about democracy, we really mean a government founded on a very large number of essentials and a very large number of interchangeables, with the influential group being almost as big as the interchangeable group. When we mention monarchy or military junta, we have in mind that the number of interchangeables, influentials, and essentials is small.

The beauty of talking about organizations in terms of essentials, influentials, and interchangeables is that these categories permit us to refrain from arbitrarily drawing a line between forms of governance, pronouncing one “democratic” and another “autocratic,” or one a large republic and another small, or any of the other mostly one dimensional views of politics expressed by some of history’s leading political philosophers.

The truth is, no two governments or organizations are exactly alike. No two democracies are alike. Indeed, they can be radically different one from the other and still qualify perfectly well as democracies. The more significant and observable differences in the behavior of governments and organizations depend on the absolute and relative size of the interchangeable, influential, and essential groups. The seemingly subtle differences between, say, France’s government and Britain’s, or Canada’s and the United States’, are not inconsequential. However, the variations in their policies are the product of the incentives leaders face as they contend with their particular mix of interchangeable, influential, and essential groups.

There is incredible variety among political systems, mainly because people are amazingly inventive in manipulating politics to work to their advantage. Leaders make rules to give all citizens the vote – creating lots of new interchangeables – but then impose electoral boundaries, stacking the deck of essential voters to ensure that their preferred candidates win. Democratic elites may decide to require a plurality to win a particular race, giving themselves a way to impose what a majority may otherwise reject. Or they might favor having runoff elections to create a majority, even though it may end up being a majority of the interchangeables’ second-place choices. Alternatively, democratic leaders might represent political views in proportion to how many votes each view got, forging governments out of coalitions of minorities. Each of these and countless other rules easily can fall within our definition of democracy, yet each can – and does – produce radically different results.

Shuffling The Essential Deck

Staying in power, as we now know, requires the support of others. This support is only forthcoming if a leader provides his essentials with more benefits than they might expect to receive under alternative leadership or government. When essential followers expect to be better off under the wing of some political challenger, they desert.

Incumbents have a tough job. They need to offer their supporters more than any rival can. While this can be difficult, the logic of politics tells us that incumbents have a huge advantage over rivals, especially when officeholders rely on relatively few people and when the pool of replacements for coalition members is large. Lenin designed precisely such a political system in Russia after the revolution. This explains why, from the October 1917 revolution through to Gorbachev’s reforms in the late 1980s, only one Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, was successfully deposed in a coup. All the other Soviet leaders died of old age or infirmity, but Khrushchev failed to deliver what he’d promised to his cronies. It is the successful, reliable implementation of political promises to those who count that provides the basis for any incumbent’s advantage.

The story of survival is not much different, although the particulars are very different, in political settings that rely on many essential backers. As even a casual observer of election campaigns knows, there is a big discrepancy between what politicians promise when making a bid for power and what they actually deliver. Once in power, a new leader might well discard those who helped her get to the top and replace them with others whom she deems more loyal.

Not only that, but essential supporters can’t just compare what the challenger and incumbent each offer today. The incumbent might pay less now, for instance, but the pay is expected to continue for those kept on or brought into the new incumbent’s inner circle. True, the challenger may offer more today, but his promises of future rewards may be nothing more than political promises without any real substance behind them. Essentials must compare the benefits expected to come their way in the future because that future flow adds up in time to bigger rewards. Placing a supporter in his coalition after a leader is ensconced as the new incumbent is a good indicator that he will continue to rely on and reward that supporter, exactly because the new incumbent has made a concerted effort to sort out those most likely to remain loyal from opportunists who might bring him down in the future. The challenger might promise to keep backers on if she reaches the heights of power, but it is a political promise that might very well not be honored in the long run.

Lest there be doubt that those who share the risks of coming to power are often thrown aside, or worse, let us reflect on the all too-typical case of the backers of Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba. Of the 21 ministers appointed by Castro (pictured in the photo above) in January 1959, immediately after the success of his revolution, 12 had resigned or been ousted by the end of the year. Four more were removed in 1960 as Castro further consolidated his hold on power. These people, once among Fidel’s closest, most intimate backers, ultimately faced the two big “exes” of politics. For the luckier among them, divorce from Castro came in the form of exile. For others, it meant execution. This included even Castro’s most famous fellow revolutionary, Che Guevara.

Che may have been second in power only to Fidel himself. Indeed, that was likely his greatest fault. Castro forced Che out of Cuba in 1965 partly because of Che’s popularity, which made him a potential rival for authority. Castro sent Che on a mission to Bolivia, but toward the end of March 1967 Castro simply cut off Guevara’s support, leaving him stranded. Captain Gary Prado Salmon, the Bolivian officer who captured Che, confirmed that Guevara told him that the decision to come to Bolivia was not his own. It was Castro’s. One of Fidel’s biographers remarked,

In a very real sense Che followed in the shadows of Frank Pais, Camilo Cienfuegos, Huber Matos, and Humberto Sori Marin [all close backers of Castro during the revolution]. Like them, he was viewed by Castro as a ‘competitor’ for power and like them, he had to be moved aside ‘in one manner or another.’ Che Guevara was killed in Bolivia but at least he escaped the ignominy of execution by his revolutionary ally, Fidel Castro. Humberto Sori Marin was not so ‘fortunate.’ Marin, the commander of Castro’s rebel army, was accused of conspiring against the revolution. In April 1961, like so many other erstwhile backers of Fidel Castro, he too was executed.

Political transitions are filled with examples of supporters who help a leader to power only to be replaced. This is true whether we look at national or local governments, corporations, organized crime families, or, for that matter, any other organization. Each member of a winning coalition, knowing that many are standing on the sidelines to replace them, will be careful not to give the incumbent reasons to look for replacements.

This was the relationship Louis XIV managed so well. If a small bloc of backers is needed and can be drawn from a large pool of potential supporters (as with the small coalition needed in places like Zimbabwe, North Korea, or Afghanistan), then the incumbent doesn’t need to spend a huge proportion of the regime’s revenue to buy the coalition’s loyalty. On the other hand, more must be spent to keep the coalition loyal if there are relatively few people who could replace its members.

That is true in two circumstances: when the coalition and real selectorate are both small (as in a monarchy or military junta), or the coalition and selectorate (whether real or nominal) are both large (as in a democracy). In these circumstances, the incumbent’s ability to replace coalition members is pretty constrained. Essentials can therefore drive up the price for staying loyal. The upshot is that there is less revenue available to be spent at the incumbent’s discretion because more has to be spent to keep the coalition loyal, fending off credible counteroffers by political foes.

When the ratio of essentials to interchangeables is small (as in rigged-election autocracies and most publicly traded corporations), coalition loyalty is purchased cheaply and incumbents have massive discretion. They can choose to spend the money they control on themselves or on pet public projects. Kleptocrats, of course, sock the money away in secret bank accounts or in offshore investments to serve as a rainy-day fund in the event that they are overthrown. A few civic-minded autocrats slip a little into secret accounts, preferring to fend off the threat of revolt by using their discretionary funds (the leftover tax revenue not spent on coalition loyalty) to invest in public works. Those public works may prove successful, as was true for Lee Kuan Yew’s efforts in Singapore and Deng Xiaoping’s in China. They may also prove to be dismal failures, as was true for Kwame Nkrumah’s civic-minded industrial program in Ghana and Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, which turned out to be a great leap backward for China.

We have seen how the desire to survive in office shapes some key revenue-generation decisions, key allocation decisions, and the pot of money at the incumbent’s discretion. Whether the tax rate is high or low, whether money is spent more on public or private rewards, and how much is spent in whatever way the incumbent wants all dictate political success within the confines of the governance structure the leader inherits or creates. And our notion of governing for political survival tells us that there are five basic rules leaders can use to succeed in any system:

Rule 1: Keep your winning coalition as small as possible. A small coalition allows a leader to rely on very few people to stay in power. Fewer essentials equals more control and contributes to more discretion over expenditures. Bravo for Kim Jong-Un of North Korea. He is a contemporary master at ensuring dependence on a small coalition. Bravo to Donald Trump. He tried to shrink the coalition by manipulating vote counting in the world’s oldest democracy. That’s not an easy thing to do.

Rule 2: Keep your nominal selectorate as large as possible. Maintain a large selectorate of interchangeables and you can easily replace any troublemakers in your coalition, influentials and essentials alike. After all, a large nominal selectorate provides a big supply of substitute supporters to put the essentials on notice that they should be loyal and well behaved or else face being replaced. Bravo to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin for introducing universal adult suffrage in Russia’s old rigged election system. Lenin mastered the art of creating a vast supply of interchangeables. Boo to Donald Trump. He foolishly tried to suppress turnout by America’s interchangeables, inducing more people to turn out to vote in 2020 and swelling the size of the selectorate, which resulted in his unintentionally swelling the size of the essential coalition needed for victory in 2020, making it bigger than had been true in 2016. Big error!

Rule 3: Control the flow of revenue. It’s always better for a ruler to determine who eats than it is to have a larger pie from which the people can feed themselves. The most effective cash flow for leaders is one that makes lots of people poor and redistributes money to keep select people (their supporters) wealthy. Bravo to Pakistan’s former president, Asif Ali Zardari, estimated to be worth up to $4 billion even as he governed a country near the world’s bottom in per capita income. Bravo to Donald Trump. He found a way to tax his foes (Democrats) heavily while lightening the tax burden on his supporters (especially wealthy Republicans).

Rule 4: Pay your key supporters just enough to keep them loyal. Remember, your backers would rather be you than be dependent on you. Your big advantage over them is that you know where the money is and they don’t. Give your coalition just enough that they don’t shop around for someone to replace you and not a penny more. Bravo to Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, who, whenever facing a threat of a military coup, managed to pay his army, keeping their loyalty against all odds well into his 90s.

Rule 5: Don’t take money out of your supporters’ pockets to make the people’s lives better. The flip side of rule 4 is not to be too cheap toward your coalition of essential supporters. If you’re good to the people at the expense of your coalition, it won’t be long until your “friends” will be gunning for you. Effective policy for the masses doesn’t necessarily produce loyalty among essentials, and it’s darn expensive to boot. Hungry people are not likely to have the energy to overthrow you, so don’t worry about them. Disappointed coalition members, in contrast, can defect, leaving you in deep trouble.

Bravo to Senior General Than Shwe of Myanmar, who made sure following Cyclone Nargis in 2008 that food relief was controlled and sold on the black market by his military supporters rather than letting aid go to the people – at least 138,000 and maybe as many as 500,000 of whom died in the disaster.

Do The Rules Work In Democracies?

At this point, you may be saying, Hold on! If an elected leader followed these rules she’d be out of the job in no time flat. That’s almost right, but not quite. Donald Trump (below) followed all but one of these rules about as closely as any freely elected leader in modern history, and he was voted out after one term. Breaking even one rule is dangerous for anyone, including democratically elected leaders.

A democratic leader does indeed have a really tough time maintaining her position while looting her country and siphoning off funds. She’s constrained by the laws of the land, which also determine – through election procedures – the size of the coalition that she needs in order to come to power. The coalition has to be relatively large and she has to be responsive to it, so she does have a problem with rule 1. But that doesn’t mean she doesn’t try to follow rule 1 as closely as she can (and all of the other rules too).

Why, for example, do state legislatures gerrymander districts? Precisely because of rule 1: Keep the coalition as small as possible.

Why do some political parties favor immigration? Rule 2: Expand the number of interchangeables, a rule Donald Trump did not adequately understand and manipulate.

Why are there so many battles over the tax code? Rule 3: Take control of the sources of revenue.

Why do Democrats spend so much tax money on welfare and social programs? Or why on earth do we have earmarks? Rule 4: Reward your essentials at all costs.

Why do Republicans wish the top tax rate were lower and have so many problems with the idea of national health care? Rule 5: Don’t rob your supporters to give to your opposition.

Just like autocrats and tyrants, leaders of democratic nations try to follow these rules because they, like every other leader, want to get power and keep it. Even democrats almost never step down unless they’re forced to. The problem for democrats is that they face different constraints and have to be a little more creative than their autocratic counterparts. And they succeed less often. Even though they generally provide a much higher standard of living for their citizens than do tyrants, democrats generally have shorter terms in office.

Political distinctions are truly continuous across the intersection of the three dimensions that govern how organizations work. Some “kings” in history have actually been elected. Some “democrats” rule their nations with the authority of a despot. In other words, the distinction between autocrats and democrats isn’t cut-and-dried.

Having laid the foundation for our new theory of politics and having revealed the five rules of leadership, we’ll turn to the big questions at the heart of the book, often using the terms autocrats and democrats throughout, to show how the games of leadership change as you slide from one extreme to the other on the spectrum of small and large coalitions. But just remember, there’s always a little mix of both words regardless of the country or organization in question. The lessons from both extremes apply whether you’re talking about Saddam Hussein or George Washington. After all, the old saw still holds true – politicians are all the same.

From Chapter 3: Staying In Power

Governance In Pursuit Of Heads

CEOs, just like national leaders, are susceptible to removal. Being vulnerable to a coup, they need to modify the corporate coalition (usually the board of directors and senior management) by bringing in loyalists and getting rid of potential troublemakers. Usually they have a large potential pool of people to draw from and prior experience to help guide their choices. But, also like national leaders, they face resistance from some members of their inherited coalition, and that may be hard to overcome.

Most publicly traded corporations have millions of interchangeables (their shareholders), a considerably smaller set of influentials (big individual shareholders and institutional shareholders), and a small group of essentials, often not more than 10 to 15 people. In a group of this size, even seemingly minor variations in the number of coalition members can have profound consequences for how a company is run. As we will see, this was particularly true for HewlettPackard (“HP”), because, as in all companies, small shifts in coalition numbers can lead to large percentage changes in the expected mix of corporate rewards.

In the case of HP, the CEO’s winning coalition made up a relatively large fraction of the real selectorate because ownership is heavily concentrated in a few hands. That is, we might count corporate coalition size in terms of the number of its members or in terms of the number of shares they own. In HP’s case, the essential bloc and the influential bloc have very few members compared to the total selectorate because the families of the company’s founders, William Hewlett and David Packard, retain significant ownership, just as was true of Ford Motor Company, Hallmark Cards, and quite a few other businesses for many years.

Involvement in a corporation can yield benefits, just like involvement in any form of government. These benefits can take the form of rewards given to everyone or private payments directed just to the essentials. In a corporate setting, private benefits typically come as personal compensation in the form of salary, perks, and stock options. Rewards to everyone – what economists call “public goods” – take the shape of dividends (an equal amount per share) and increased stock value.

When the winning coalition is sufficiently large that private rewards are an inefficient mechanism for the CEO to buy the loyalty of essentials, public goods tend to be the benefit of choice. Usually, coalition members are eager to receive private benefits. However, dividends and growth in share value are preferred over private rewards by very large shareholders who also happen to be in the winning coalition – this makes them the biggest recipients of the rewards that go to all shareholders. That was precisely the situation in HP, where the Hewlett and Packard families owned a substantial percentage of the company.

Who makes up the essentials in a corporation? The coalition typically includes no more than a few people in senior management and the members of the board of directors. The board usually includes a mix of senior managers in the company, representatives from large institutional shareholders, handpicked friends and relatives of the CEO (generally described as “civic leaders,” no doubt), and the CEO herself. In the parlance of economists who study corporations, the makeup of these boards boils down to insiders (employees), gray members (friends, relatives), and outsiders. One part of any corporate board’s duties is to appoint, retain, or remove CEOs. Generally CEOs keep their job for a long time, and that certainly was true of HP’s first CEO, founder David Packard. He was replaced in 1992 by an insider, Lewis Platt, who had worked for the firm since the 1960s. Platt retired in 1999 and was replaced by outsider Carly Fiorina. The HP board has repeatedly deposed CEOs since then.

It should be obvious that any board members involved in deposing the former CEO have the potential to be a problem for a new CEO. Since they have already been coup makers, there is little reason to doubt that they stand ready to start trouble once again if they think the circumstances warrant it. And what could those circumstances be but application of one or more of the rules of governance we set out earlier, especially if that application harms their interests?

Research into CEO longevity teaches us, not surprisingly, that time in office lengthens as one maintains close personal ties to members of the board. Just as sons and daughters may make attractive inheritors of the mantle of power in a dictatorship, friends, relatives, and fellow employees can generate the expectation of more loyal supporters after power is achieved. This logic probably contributed to Lewis Platt’s elevation to CEO of HP. Putting more outsiders on a board translates on average into better returns for shareholders, a benefit to everyone. At the same time, it also translates into greater risk for the CEO. Since the CEO’s interest is rarely the same as the shareholders’ interest, CEOs prefer to avoid outsider board members if they can.

Corporate problems, especially those serious enough to result in the ousting of a sitting CEO, can serve to galvanize attention and enhance oversight by the board, making existing coalitions less reliable. Furthermore, it is likely that the new CEO will face real impediments to his efforts to create and shape a board of directors in the wake of an older CEO’s deposition. After all, the old board members did not get rid of the prior incumbent with the idea that they would also make it easy for the successor CEO to get rid of them. Nevertheless, any new CEO worth her salt will try to do just that. The long-lasting CEOs are the ones who succeed.

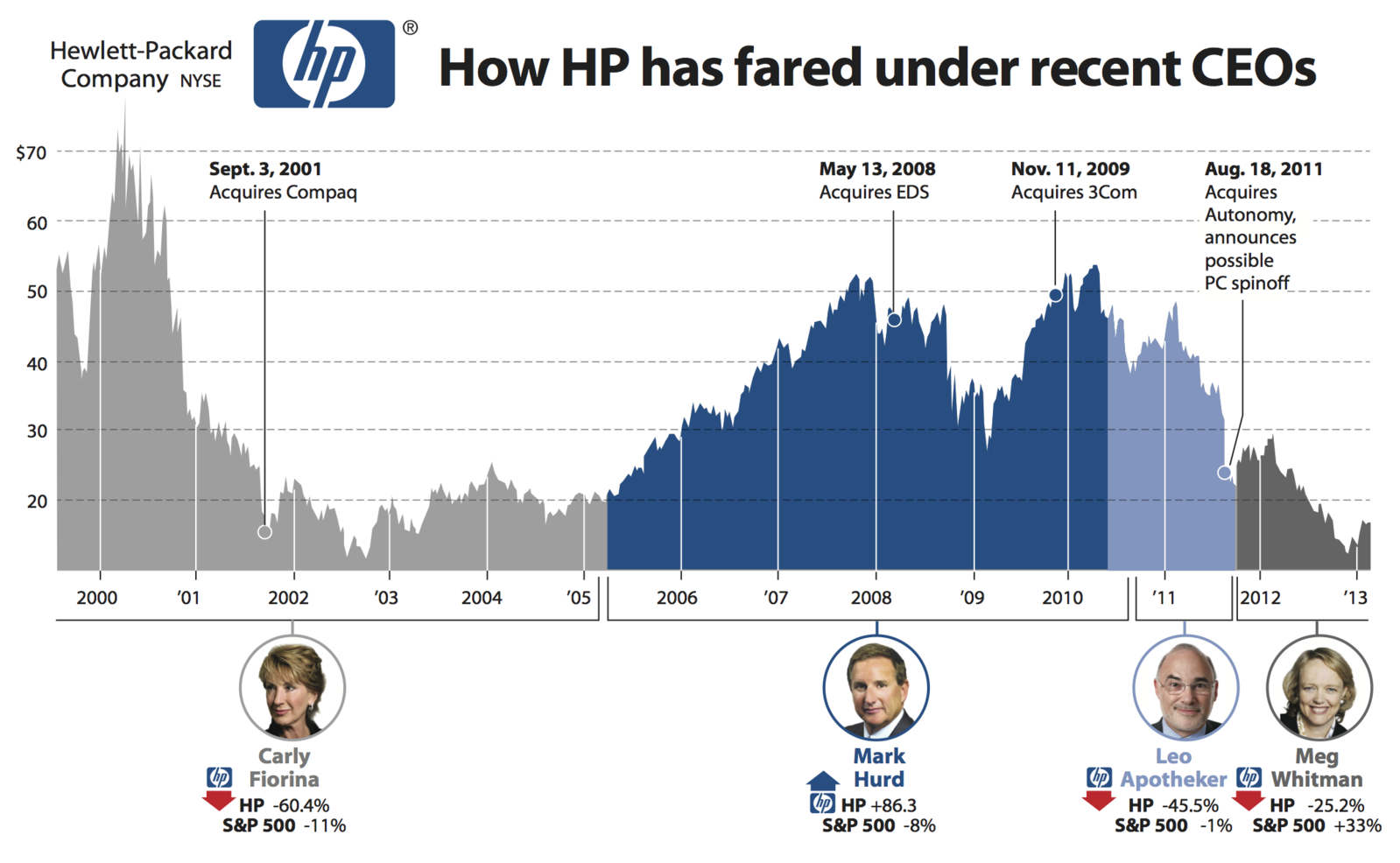

Carly Fiorina (above) became Hewlett-Packard’s CEO in 1999. After six turbulent years she was deposed from that position and as chair of the board. Prior to being removed she was the target of an unsuccessful proxy fight mounted by Walter Hewlett and David Woodley Packard, sons of HP’s founders.

The board, in keeping with the power of inherited insider influence, also included Susan Orr, founder David Packard’s daughter. All were individuals with big financial stakes in HP. Furthermore, as big shareholders Hewlett, Packard, and Orr were more concerned about HP’s overall performance than about any private benefits they got from being on the board. Good news for shareholders – potentially bad news for Fiorina. The board that selected Fiorina as CEO consisted of 14 members. As we’ve seen, three were relatives of HP’s founders; three more were current or retired HP employees. Fiorina’s initial board, in other words, had a substantial group of insiders and gray members who were not of her choosing and who had big stakes in the corporation’s stock value. It is not hard to see that Carly Fiorina needed to make changes to build a leaner board with stronger attachments to her. It would not be easy – while the board had selected her to be CEO, they were not her handpicked loyalists.

She achieved results nonetheless. A year after Fiorina’s ascension, in 2000, HP’s proxy statement to its shareholders listed only 11 board members, 20% fewer than the group that selected her. Three, including David Woodley Packard, were gone. As Fiorina became more entrenched in her position, the board continued to shrink – the 2001 statement listed only 10 board members, a reduction of nearly 30% from the board she’d originally inherited. Seemingly growing more secure in her control, Fiorina launched an effort to merge HP with Compaq, an effort with both beneficial prospects and serious risks for her continued rule.

Naturally, Fiorina presented the merger as a boon for HP and its shareholders. As Fiorina explained in a speech at a conference on February 4, 2002, “It is a rare opportunity when a technology company can advance its market position substantially and reduce its cost structure substantially at the same time. And this is possible because Compaq and HP are in the same businesses, pursuing the same strategies, in the same markets, with complementary capabilities. So, yes, we thought about a go-slow approach. But, we concluded, after two-and-a-half years of careful deliberation and preparation, that standing still had enormous risks…. Standing still means choosing the path of retreat, not leadership.”

There is no reason to doubt the sincerity of Fiorina’s expectations for the Compaq merger. But it is instructive to examine a major indicator of how Fiorina’s appointment and her views meshed with broader market sentiments. The day before the announcement of Carly Fiorina’s appointment as HP’s new CEO, HP’s shares traded at $53.43.

The market’s reaction to her appointment can reasonably be described as uncertain. The price of HP shares was flat immediately following the announcement and then began to decline, falling to under $39 by mid-October 1999, about three months later. Of course, markets are forward looking, and so investors were watching and learning, modifying their expectations as Fiorina took charge. The news and modified expectations must have been good for a while because by early April 2000, HP’s shares had risen markedly, to about $78. But good feelings and good circumstances were not to prevail for long. After April 7, 2000, the share price went into a tailspin, bottoming out in September 2002 at around $12 a share and significantly underperforming the major stock market indexes. By the time Fiorina resigned in February 2005, HP’s share price had only rebounded to about $20.

With respect to the Compaq merger, the market was similarly pessimistic. The plan to merge with Compaq was announced on September 3, 2001. Share prices rose on the news, with a peak in December of that year of about $23, though that was still well below the value the day before Carly Fiorina became CEO. Over the period from July 1999 (the announcement of Fiorina’s appointment) to the end of December 2001, the adjusted Dow Jones index fell 9.4% while HP’s adjusted share price fell 47%.

From the perspective of any big investor in HP, including the Hewlett and Packard families, Fiorina must have looked like a disaster. Their company was doing worse than the general stock market; their fortunes were being hammered. She was a CEO in trouble. Nevertheless, the upward tick in the share value indicated a renewed, if temporary, boost of optimism at the announced intention to merge with Compaq. But markets don’t like infighting, and when Walter Hewlett and David Woodley Packard declared their opposition to the merger, the gains were reversed.

Soon the price collapsed even further, halving as it became apparent that there was to be a proxy fight in which Hewlett and Packard sought to muster support from enough shareholders to defeat the board’s proposed slate at the corporation’s annual meeting. No doubt Fiorina realized that she was going to be in for a tough time, perhaps even before her public announcement of the intended and eventually successfully completed merger. It also seems likely that she would already have known Hewlett’s and Packard’s views. We can only conclude that this was an intentional gamble on a major policy shift, one that could – and did – adversely affect the wealth of HP’s large shareholders (such as now-former board members Hewlett and Packard).

Looking at the Compaq-HP merger politically, we can see several critical themes emerging. Fiorina was already in some trouble because of declining share value. She had successfully diminished the board’s size and shuffled its membership, both wise choices for a CEO seeking longevity in office. Yet despite these actions, she still faced significant opposition from the inner circle of essentials and influentials. She had not yet secured the board’s loyalty. The Compaq merger might have made good business sense and could therefore have been good for the stock price, thus softening internal opposition to her. Or else, seeing the merger as a fait accompli, her opponents might have given up their fight. That didn’t happen. And the disgruntled board members, heavily invested as they were in HP’s stock value, could not be mollified with private rewards.

However, what in retrospect may seem like a political nonstarter held at the time great political advantages. For instance, what had to be an implication of Fiorina’s multibillion-dollar merger with Compaq for the board composition? Once the deal was sealed, Fiorina would have to bring some Compaq leaders onto the post-merger HP board. This could be done either by expanding the existing board to accommodate Compaq influentials or by pruning the existing board to make room for the new Compaq representatives drawn from Compaq’s selectorate. Fiorina apparently saw that the merger would provide an opportunity to reconstitute the board and potentially weaken the board faction that opposed her. That seems to be exactly what she tried to do.

Of course, her rivals would not sit idly by and be purged. Unless such a purge can be accomplished in the dark, presented as a fait accompli to the old group of influentials, the risk of failure is real. As it happens, Securities and Exchange Commission regulations require disclosures, which makes turning a board purge into a fait accompli extremely difficult when the opportunity to purge the board depends on a prospective merger.

There are two potential responses to a rebellion such as the one Fiorina faced over HP’s weak share price and the Compaq merger. CEOs can either purge some essentials and boost the private benefits to remaining coalition members, or they can expand the coalition and increase rewards to the general selectorate of interchangeables (that is, shareholders). Having survived the proxy fight in 2002, Fiorina faced an 11-member board that included five new members carried over from Compaq as part of the merger. HP’s board had shifted materially, with only six previous HP board members on it.

Since Fiorina had been the mover and shaker behind the Compaq deal, it is reasonable to believe that she assumed the new members would be likely to work with her as opposed to lining up with board members who had supported Walter Hewlett’s fight against the merger. Walter Hewlett and Robert P. Wayman, meanwhile, had left the board. By this time, in 2002, Fiorina had expanded the total board size by only one, from 10 to 11, while overseeing the departure of several old board members at the same time to make room for five Compaq representatives. Surely she had reason to believe she now enjoyed the support of a majority of the new board.

Perhaps in an effort to shore up the support of remaining old hands on the board, or perhaps coincidentally, there also was a notable shift in board compensation. Just before Fiorina became HP’s head, board members earned compensation (that is, private benefits) that ranged from $105,700 to $110,700. With Fiorina in office and the board diminished in size, this amount dropped slightly to $100,000 to $105,000 and remained there in the years 2000 to 2003. But in 2004, according to HP’s 2005 proxy statement, board members received between $200,000 and $220,000. During the same period, dividends remained steady at 32 cents a share annually and HP’s shares significantly underperformed the main stock market indexes. Clearly something was up: HP’s stock price performance was poor; dividends were steady; and directors’ pay had doubled.

Fiorina’s board shuffling and their improved compensation seem aimed at getting the right loyalists in place to help her survive. Although the Compaq merger resulted in the board’s growing from 10 to 11, what is most noteworthy is that this net growth of one member was achieved while adding five new members (one of whom stepped down at the end of the year). So the old members constituted only about half the board, shifting the potential balance of power toward Fiorina. Presumably that is just what she hoped, although it is not how things turned out.

Expanding the board was not, and generally is not, the optimal response to a threat from within. To her credit, in terms of political logic, she significantly expanded the size of the interchangeables by adding Compaq’s shareholders to HP’s shareholders. This normally helps to induce strengthened loyalty, but declining share value could not have been good for new HP board members who had been heavily invested in Compaq, since their economic well-being was now tied to HP’s share performance. Nor could Fiorina mollify HP’s large shareholders on the board with better board compensation, since their welfare depended on producing the public good of greater returns to shareholders. Those gray board members who owned lots of shares made the seemingly small board of 11 actually pretty large in terms of shares they could vote.

Under enormous pressure, Carly Fiorina stepped down. She was replaced by Patricia Dunn as chairwoman, with HP’s chief financial officer, Robert Wayman, emerging again as a significant HP player. He was made interim CEO. Wayman, unable or uninterested in translating his interim position into a full-time job, stepped down a month later while continuing in his role as a member of the board and an HP employee. Mark Hurd replaced him as CEO.

In the immediate aftermath of Fiorina’s ouster, the board separated two key positions, CEO and chair, presumably in a good Montesquieu-like effort to promote the separation of powers and protect themselves against future adverse choices by the CEO. If that was their intention, they certainly failed. Following Hurd’s ascent to the position of CEO, he successfully brought the two posts back under one person’s control: his own.

Within a year of Fiorina’s ouster, all the leading coup makers who acted against her were gone. Mark Hurd had risen to the top, and, as suggested by the quote from Italo Calvino, he had to watch day and night to keep his head. Four years later, despite stellar HP performance, Hurd was forced out amid a personal scandal. This is the essential lesson of politics: in the end, ruling is the objective, not ruling well.

The Perils Of Meritocracy

One lesson to be learned from Mark Hurd’s ultimate removal at HP is that doing a good job is not enough to ensure political survival. That is true whether one is running a business, a charity, or a national government. How much a leader’s performance influences the length of his tenure in office is a highly subjective matter. It might seem obvious that it is important to have people in the coalition of key backers who are competent at implementing the leader’s policies. But autocracy isn’t about good governance. It’s about what’s good for the leader, not what’s good for the people. In fact, having competent ministers or competent corporate board members can be a dangerous mistake. Competent people, after all, are potential (and potentially competent) rivals.

The three most important characteristics of a coalition are 1) loyalty, 2) loyalty, and 3) loyalty. Successful leaders surround themselves with trusted friends and family, and rid themselves of any ambitious supporters. Carly Fiorina had a hard time achieving that objective, and as a result she failed to last long. Fidel Castro, by contrast, was a master (of course, he had fewer impediments to overcome in what he could do than did Fiorina), and he lasted in power for nearly half a century.

From the book The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior Is Almost Always Good Politics by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith. Copyright © 2011 by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith. Reprinted by permission of PublicAffairs, an imprint of Basic Books Group, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc., New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Let us know what you are reading this summer by sharing your current book list to [email protected].

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD