Why Most Gold Mining Stocks Are Terrible Investments

| This is Porter & Co.’s The Big Secret on Wall Street, which we publish every Thursday at 4 pm ET. Once a month, we provide to our paid-up subscribers a full report on a stock recommendation, and also a monthly extensive review of the current portfolio… At the end of this week’s issue, paid-up subscribers can find our Top 3 “Best Buys,” three current portfolio picks that are at an attractive buy price. You can go here to see the full portfolio of The Big Secret. Every week in The Big Secret, we provide analysis for non-paid subscribers. If you’re not yet a subscriber, to access the full paid issue, the portfolio, and all of our Big Secret insights and recommendations, please click here. |

It used to be a house.

Now, it was just a tiny roof-peak triangle… poking out of 18 feet of “slickens.”

Above all else, California farmers in the 1860s dreaded the slickens – a deadly landslide of mud and silt kicked up by the new-fangled hydraulic gold mining machine. The slickens could – and did – bury hundreds of acres of farmland in one blast… as happened to poor George Briggs, who in 1861 lost 58,000 fruit trees in a single day and had to leave town and start his life over.

The miners had little sympathy for George, or for his neighbor with the buried farmhouse. That’s just what happens when you’re in the way of the first large-scale mechanized gold mining operation in history.

Just a few years after a sawmill operator spotted gold flakes in the water at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, enticing 300,000 fortune seekers to what would be called the Golden State, the California gold rush had slowed to a crawl. Placer mining, the classic panning-for-gold technique where prospectors swirled water in containers to catch gold flakes at the bottom, had turned up all the easily available nuggets. By 1852, pay dirt was scarce, with gold miners, on average, bringing in $6 a day, down from 1848’s daily payloads of $20.

Discouraged, plenty of gold bugs packed up their prospecting equipment and headed back East. Plenty more – like George Briggs, a one-time prospector – stuck around in California and decided to make a go of less glamorous endeavors like fruit growing.

But some die-hard miners remained convinced that there was “gold in them thar hills” – and in order to find it, they’d just have to move the hills.

Enter Anthony Chabot, the “Water King,” and his superpowered hydraulic mining machine.

Sometime in 1853, Chabot and a friend (who’d likely be recording pranks on YouTube today) ginned up a high-pressure water cannon out of a canvas hose, a metal funnel, and a few pieces of wood – and were impressed with how quickly it transformed a small hillside into a heap of rocks.

This device had clear implications for the gold mining market. Before long, the pair had created and marketed a series of bigger and better models – developing an 18-foot-long cannon that could blast 500 gallons of water 400 feet in the air. “Those streams directed upon an ordinary wooden building would speedily unroof and demolish it,” a newspaper of the time reported.

The new technology – aimed at rocky hillsides and river banks – also worked brilliantly to bring gold to light. Between 1860 and 1880, hydraulic mining added hundreds of employees and $170 million (in 1860 dollars) to California’s economy, and the number of millionaires in California outpaced totals in New York and Boston. Lucrative picks-and-shovels businesses – like aqueducts for transporting water to the mines – sprang up across the state, with some 5,000 miles of pipeline shunting millions of gallons to the gold mines by 1858.

But it turned out, flattening California’s topography with a giant pressure washer also led to soil erosion – slickens – and a state full of angry farmers.

Nevada, Placer, and Yuba counties – the sites of the most intense mining operations – were soon pockmarked by sediment, debris, floodwater, and eroded hills… and by destroyed wheat crops that had been worth as much as $800,000 per farm. After a long-drawn-out series of complaints and injunctions, California’s fruit and grain growers finally in 1884 won a case known as the Sawyer Decision, and the California government agreed to ban hydraulic mining. By then, of course, irreparable damage had been done to its ecosystem, with a canyon-sized pit of soil erosion still visible today at Diggins State Park, once the site of California’s largest hydraulic mine.

And still, the yellow metal beckoned… from ever deeper underground.

In place of hydraulic mining, gold miners now turned to dredges… dynamite… drills… and as the decades rolled on, high-tech, heavy-duty excavation machines. The Water King’s hydraulic hose was the dawn of a new era for gold mining – the capital-intensive era – one that’s still going on today, all over the world.

A century and a half later, the over $200 billion global gold mining industry is still gobbling up billions of dollars in labor, energy, and ever more expensive and elaborate equipment as gold (a finite resource) gets harder and harder to find.

This unfortunate reality is why we don’t often recommend gold miners… and why we’ll tell you that, frankly, most of them suck.

Most Gold Miners Underperform Gold In The Long Run

Over the past half century, the price of gold has risen more than 7,500% in U.S. dollar terms. Yet, over the same period, gold stocks – as tracked by the Barron’s Gold Mining Index (BGMI) – have risen only 1,000% (versus 6,300% for the S&P 500).

This is dramatic long-term underperformance for an asset that supposedly represents leveraged exposure to the underlying price of gold. However, as you can see in the chart below, this underperformance really started to accelerate around the time of the Global Financial Crisis.

Gold and gold stocks both fell sharply in the early stages of the Global Financial Crisis. However, gold recovered quickly and made substantial new highs before peaking at just under $2,000 an ounce in late 2011.

Gold stocks, meanwhile, barely managed to return to their pre-crisis highs during this time. And they’ve continued to languish well below those highs ever since, even as gold itself has gone on to make new all-time highs above $2,700 per ounce over the past few years.

Market correlations put this shift in perspective. Between January 1970 and August 2008 – just before the collapse of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – gold and gold stocks had a strong correlation of 0.9, meaning they moved together roughly 90% of the time. Since September 2008, this correlation has fallen to only 0.35.

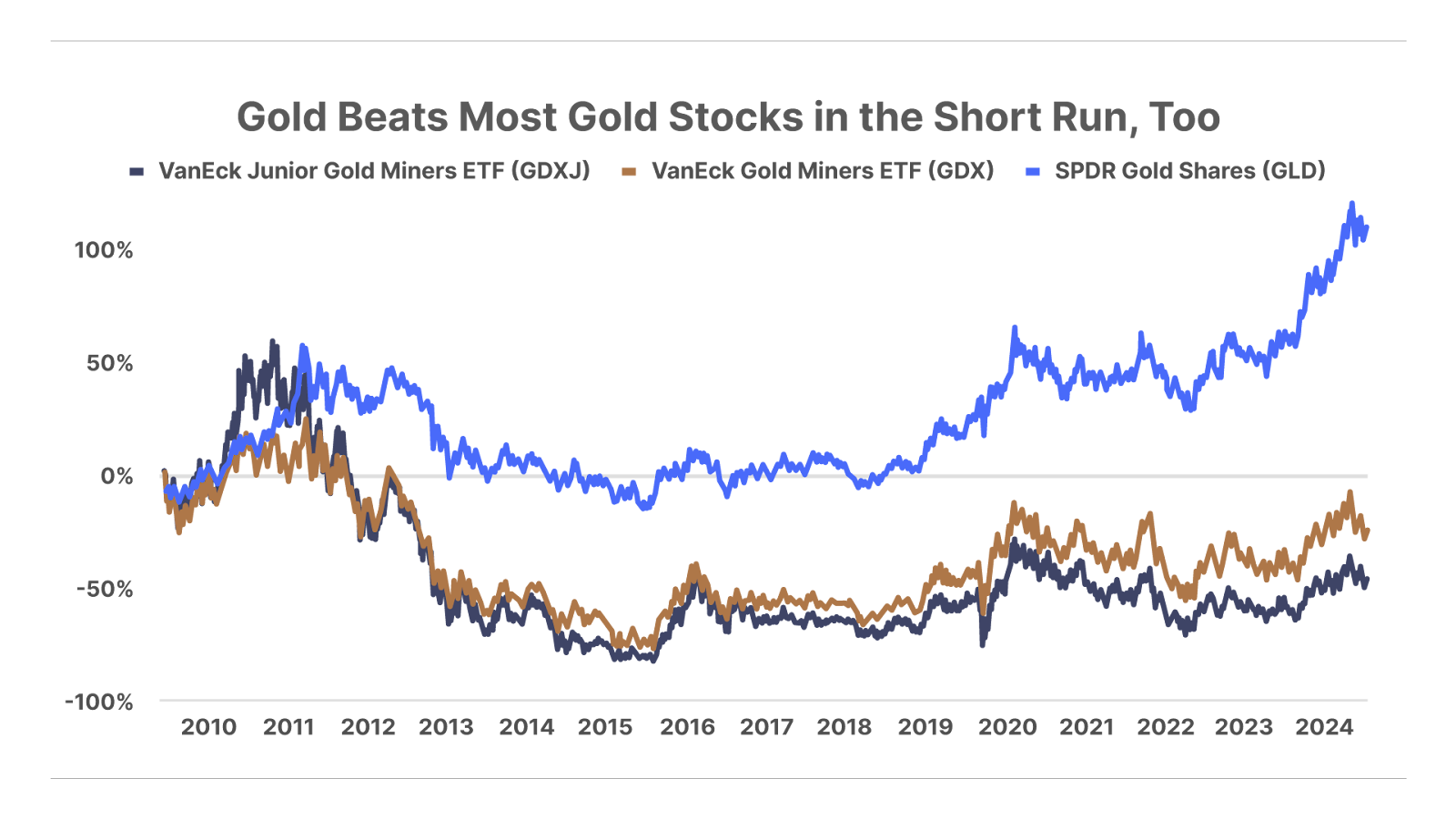

This shift can also be seen in the recent performance of the most popular gold and gold stock exchange-traded funds (“ETFs”): the SPDR Gold Trust ETF (GLD), the VanEck Vectors Gold Miner ETF (GDX), and the VanEck Junior Gold Miners ETF (GDXJ).

Since December 2009 – the earliest period when all three of these ETFs were available – GLD (tracking the price of the metal) has risen more than 100%, while GDX and GDXJ (tracking stocks) have declined 22% and 56%, respectively.

What accounts for the poor relative performance of most gold miners versus gold? The answer is relatively simple…

Gold Mining Is (Generally) A Terrible Business

Here at Porter & Co., we believe investing in high-quality, capital efficient companies for the long run is the surest way to build generational wealth in the stock market. However, most gold miners are incredibly capital inefficient.

Mining gold has always required a lot of work – and a lot of money. But mining has become an increasingly capital-intensive endeavor as gold has become ever more challenging to find.

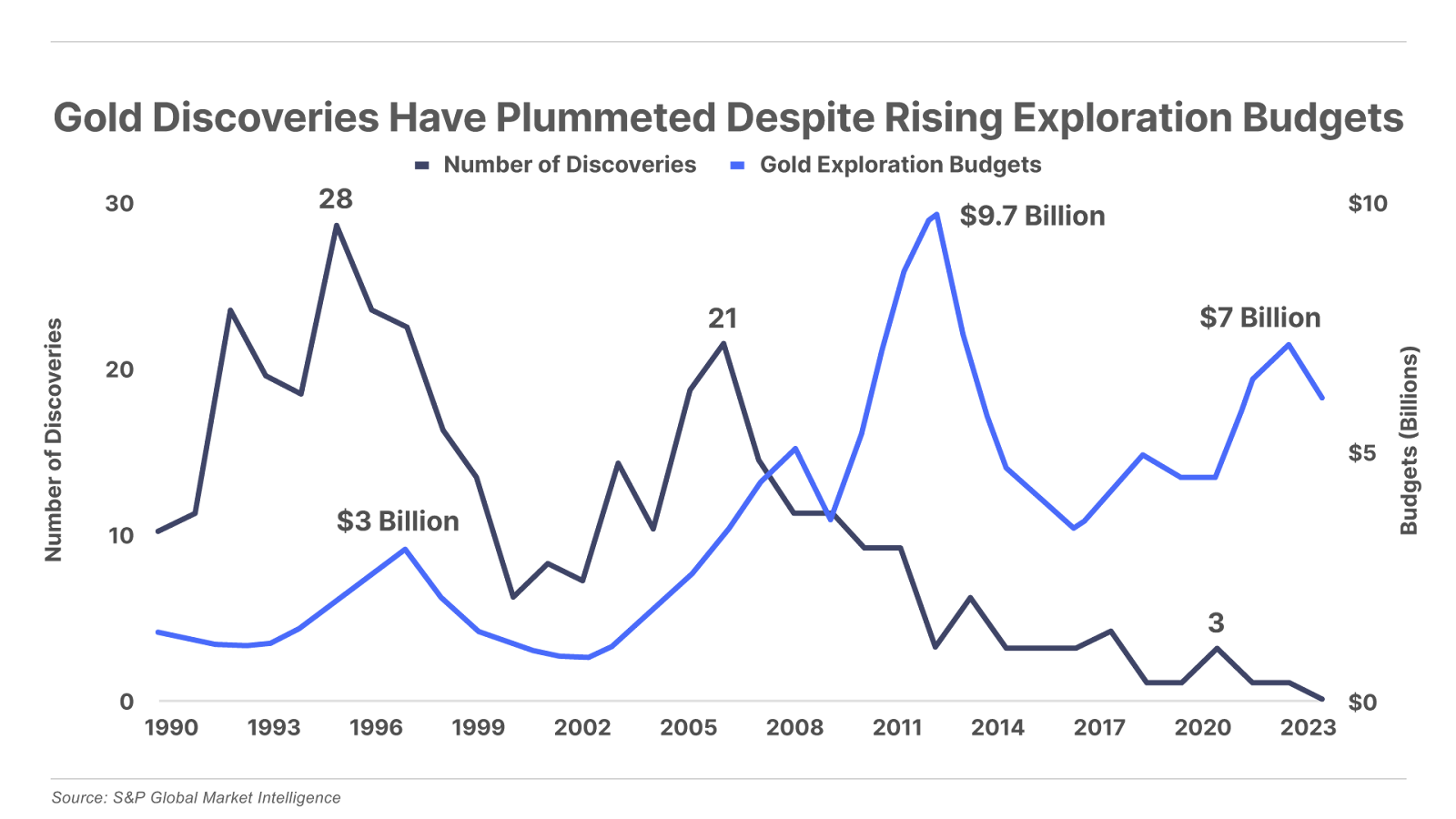

As shown in the chart below, despite a near tripling in gold miners’ exploration budgets, the number of new gold discoveries have plummeted over the past few decades.

The volume of new gold reserves has also plunged over this time.

This means discovering an ounce of gold has become much more expensive.

Getting permits for new mines has also become increasingly difficult. The process has become complex and time-consuming, even in mining-friendly countries like the U.S. and Canada. Thus, obtaining permits takes ever more effort and resources, resulting in higher costs.

Finally, even when projects are permitted, governments are demanding larger ownership stakes and higher production taxes. In some less friendly jurisdictions, they may decide to seize a mine outright. This occurred most recently last October, when the Malian government nationalized the Yetala gold mine previously owned by miners AngloGold Ashanti and Iamgold.

All these factors have caused mining capital expenditures (“capex”) to soar over the past several decades. And unfortunately, data suggest actual capital costs are routinely even bigger than companies project.

A 2019 study from consultancy McKinsey & Company showed that only 20% of gold mines with an expected capex of $500 million or more experienced no cost overruns before completion.

Meanwhile, almost half (44%) were required to spend 15% to 100% more on capex to complete their mines than initially planned. And nearly one in five (19%) ultimately spent over 100% more than planned.

Higher Gold Prices Are A Double-Edge Sword

The high costs of gold mining don’t end once a mine is built. Operating a gold mine is also expensive, and counterintuitively, these costs tend to move higher along with the price of gold.

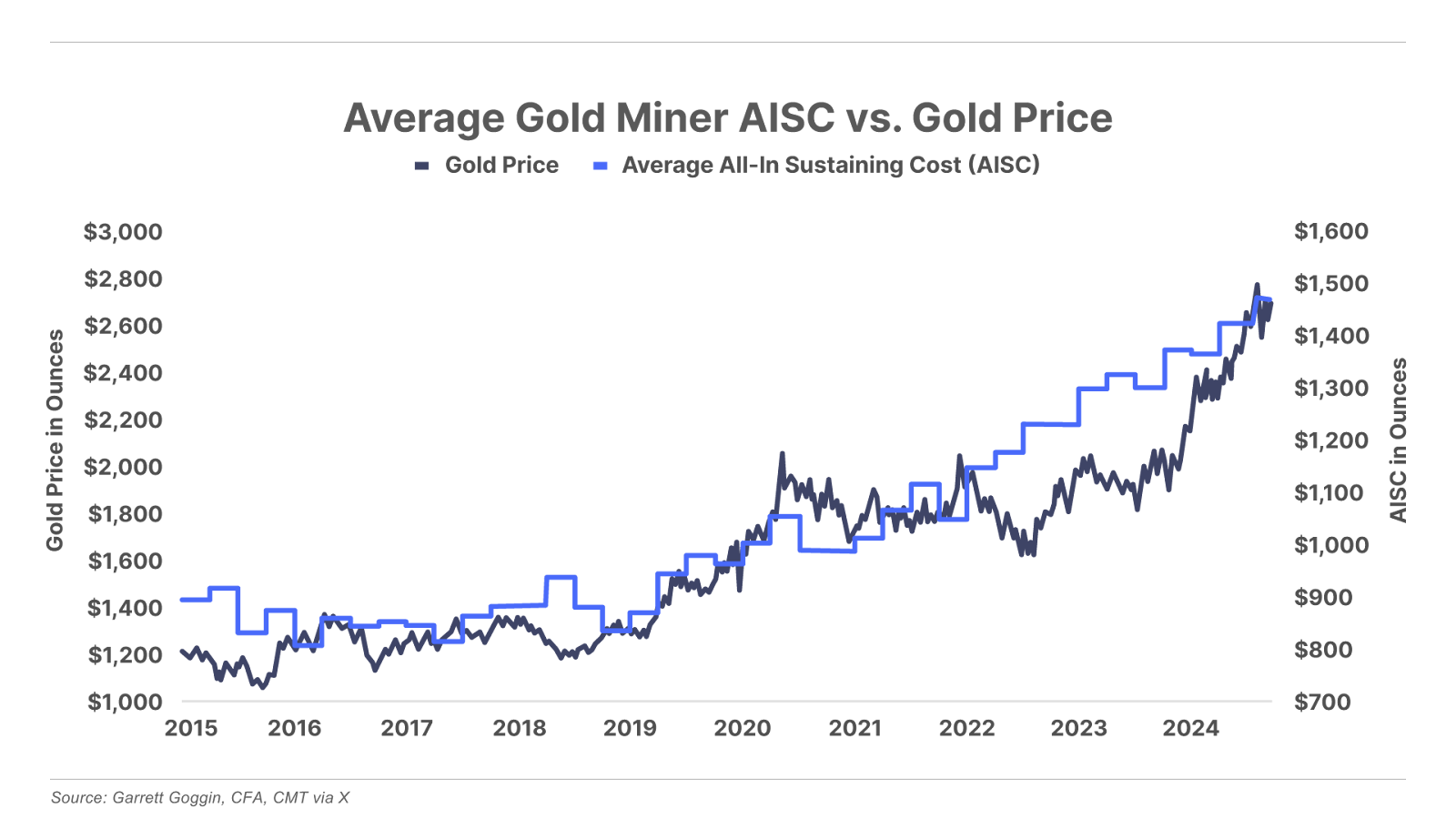

Tracking precise gold production costs over the long term is difficult, as the industry standard for reporting these costs – known as all-in sustaining cost (“AISC”) – has only been around since 2012. However, a chart of this measure over the past 10 years shows that these costs have moved quite closely with the price of gold over that time.

There are several logical reasons for this relationship…

First, a significant percentage of a miner’s production cost is often directly tied to the price of gold. This includes taxes to local and national governments and royalties paid to financing companies.

As gold prices rise, miners are also incentivized to develop less economically viable gold deposits with higher production costs, which they might not have been able to mine at lower gold prices. Similarly, higher gold prices incentivize the building of new mines with greater capex.

Second, the largest single driver of higher gold prices over time is monetary inflation (aka money printing), which also tends to drive up many of the individual inputs into the cost of gold production. This explains the sudden worsening in gold miners’ performance versus gold since 2008, when the Federal Reserve began to ramp up massive monetary inflation in response to the crisis, a trend that has only accelerated since COVID.

According to a 2018 study by precious metals trading platform Goldmoney, labor (39%), fuel and power (20%), and consumable goods (20%) account for nearly 80% of a typical miner’s production cost. Like gold itself, the cost of each of these items is highly correlated to increases in the money supply.

In short, the higher gold prices go, the higher most gold miners’ production costs go. In fact, in some cases, miners’ production costs can rise even faster than their realized gains from higher gold prices, meaning their margins can decline as the price of gold moves higher.

Of course, there are exceptions to every rule. Companies with excellent management teams, better deposits in favorable jurisdictions, and lower-than-usual capex and production costs can significantly outperform the broad gold mining indexes. Similarly, early-stage exploration companies and miners with significant exploration potential may be more highly correlated to gold prices.

However, the capital inefficient nature of most publicly traded gold miners is why we generally don’t recommend investing in them. Instead, we prefer to invest in what are known as gold streaming companies.

Rather than exploring and digging for gold like typical miners, these companies provide financing to gold mining companies to do the dirty work of pulling metal out of the earth. In exchange for providing this capital, they earn a percentage of the mine’s output.

This lucrative arrangement makes streaming companies incredibly capital efficient, and a fantastic way to get leverage to the underlying price of gold.

Paid-up Big Secret on Wall Street subscribers already have access to in-depth research on our favorite gold streamer, which is also one of our current Top 3 “Best Buys.” If you’re not yet a subscriber, click here to get started now.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.