Breaking the Billion-Dollar Barrier

The Last Time This Happened, Investors Earned a 2,000% Return

| Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email Lance, our Customer Care Concierge, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected].

Paid subscribers can also access this issue as a PDF on the “Issues & Updates” page here. |

“The secret ingredient comes from bull testicles.”

In the early 1990s, this wildfire rumor about the source of the mystery chemical taurine in Red Bull energy drinks was – in hindsight – genius.

For most consumer-product companies, it would have been a public relations nightmare. But for Red Bull founder Dietric Mateschitz, it was a manna-from-heaven marketing moment. And it helped make him one of the world’s wealthiest men.

The bull balls story begins a decade earlier in Thailand, when Mateschitz – then a 38-year old marketing executive for Blendax, Europe’s largest toothpaste maker – discovered the energy-boosting effects of taurine. Suffering from a severe case of jet lag, Mateschitz consumed a local drink called Krating Daeng, which Thailand’s laborers chugged to grind through 12-hour shifts of punishing manual labor.

The mystery tonic, containing sugar, caffeine, B vitamins, and taurine, instantly brought the weary Mateschitz back to life. The drink’s effectiveness made him wonder why the magical elixir had not made its way to the west.

Spoiler alert: taurine does not, in fact, come from a bull’s nether regions. It’s a naturally occurring amino acid in humans, and was first put into drink form in the 1960s after the Japanese government outlawed amphetamines – better known as speed. In 1962, experimenting with a safer energy-boosting alternative, a Japanese pharmaceutical company came up with an “energizing tonic” containing a synthetic taurine and caffeine. Branded as Lipovitan, it was the world’s first energy drink.

Taurine-based energy drinks became popular throughout Asia by the mid-1980s, but they had yet to reach the U.S. and Europe. Mateschitz saw a massive opportunity to unleash such an energy product on the west.

In 1984, he quit his corporate job and poured his life savings of $500,000 into a partnership with the owners of the Krating Daeng. Mateschitz swapped 51% of his new company for the rights to distribute the drink internationally. He called it Red Bull – the English translation of Krating Daeng.

Mateschitz understood that the value of a consumer product was in its branding – rather than in the capital-intensive business of actually making the product and getting it to consumers. So he outsourced Red Bull’s bottling and distribution, and focused on building the brand.

He then spent the next three years developing Red Bull’s marketing and branding strategy. The perfectionist Materschitz went through 50 different iterations on the can design. Finding the right slogan was an even tougher battle.

Mateschitz’s college friend Johannes Kastner, who owned an ad agency, agreed to develop the slogan for free. For the next 18 months, Mateschitz rejected every proposal that came across his desk. Exasperated, Kastner threatened to walk.

Mateschitz convinced him to think about it for one more day. Tossing and turning in his sleep that night, inspiration struck at 3 a.m. Kastner phoned Mateschitz and gave him his last idea – “Red Bull gives you wings.”

Mateschitz loved it… and with that, Red Bull was ready to launch.

By the time Mateschitz put the first Red Bull drinks on store shelves in his home country of Austria in 1987, the company’s finances were running on fumes.

Red Bull Goes Full Guerilla

With no cash for a media campaign or advertising, Mateschitz put together what became one of the world’s most successful guerrilla marketing campaigns – an unconventional strategy that delivers maximum brand exposure at minimal cost.

He arranged to strew thousands of empty Red Bull cans in places popular with young men, his target demographic. The Potemkin village of demand, near bars, college campuses, concerts, and nightclubs across Europe, in turn generated real demand.

The company’s next guerrilla marketing effort was to then deploy battalions of scantily-clad “Red Bull Girls” to hand out samples in college libraries during midterms, or outside pubs during peak hours.

These successful, though small scale, early efforts bootstrapped the Red Bull brand into local European markets in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

But it was the testicular-based taurine rumors that took Red Bull to the next level. Possibly started by Red Bull itself, the rumor quickly spread across Europe and then the world.

Mateschitz instantly embraced the bull-ball story. As a seasoned marketer, he knew that any press was good press.

He designed an entire PR and marketing strategy to fan the flames, including an entire page on the company’s website dedicated to the far-fetched tale.

The bull-testicle rumors became a global phenomenon, boosting Red Bull’s brand. It became one of the world’s first viral marketing campaigns.

Red Bull sales boomed. Then came the controversy.

Several high-profile deaths were reported from high school athletes and college party-goers, who reportedly consumed several cans of Red Bull before they died.

Red Bull was not found legally liable for the deaths, but the news sparked a backlash against the brand. France imposed a nationwide ban on Red Bull in 1998, and the European press labeled the drink “speed in a can” and “liquid cocaine.” High schools banned Red Bull.

As it happened (and as any parent might have predicted), telling teenagers what not to do – what they weren’t allowed to drink – was more marketing gold for Red Bull. In a 2010 Bloomberg interview, when asked if the rumors and controversy were all part of a master marketing plan, Mateschitz replied:

“Yes. We expected it. It was a part of the strategy from the beginning. We would make the brand interesting enough that people wanted to get their hands on it.”

By the year 2000, Red Bull was a global phenomenon, selling more than a billion cans per year across 50 countries. Booming sales provided Red Bull with a war chest to up the ante on its shock-and-awe marketing campaign. The company invested heavily into sponsorships and endorsement partnerships, focusing on extreme sports and daredevil athletes who gained international notoriety for pulling off out-of-this-world stunts… literally.

Perhaps most famously, Red Bull spent $30 million to sponsor the world’s boldest sky-diving jump… from space.

On October 12, 2012, Austrian daredevil Felix Baumgartner jumped out of a helium balloon 24 miles above Earth’s surface, wearing a Red Bull-branded space suit:

Baumgartner set world records for the highest skydive and the fastest speeds reached during a free-fall descent. He maxed out at 843.6 miles per hour – faster than a jetliner. The event was broadcasted by 40 TV stations and 130 digital news outlets.

In the days that followed, the stunt was derided as ludicrous and reckless. The outrage only further promoted Red Bull’s brand and sales – playing perfectly into Mateschitz’s marketing master plan.

By the time Mateschitz passed away in 2022 at age 78, Red Bull had made him one of the world’s richest men, with a net worth of $27 billion.

Guerilla marketing was only part of the source of Red Bull’s success. The company’s early decision to outsource the bottling and distribution made it an incredibly capital efficient enterprise that could distribute a huge chunk of earnings to its owners each year. In 2021, for example, Mateschitz earned $865 million in dividends from (privately held) Red Bull.

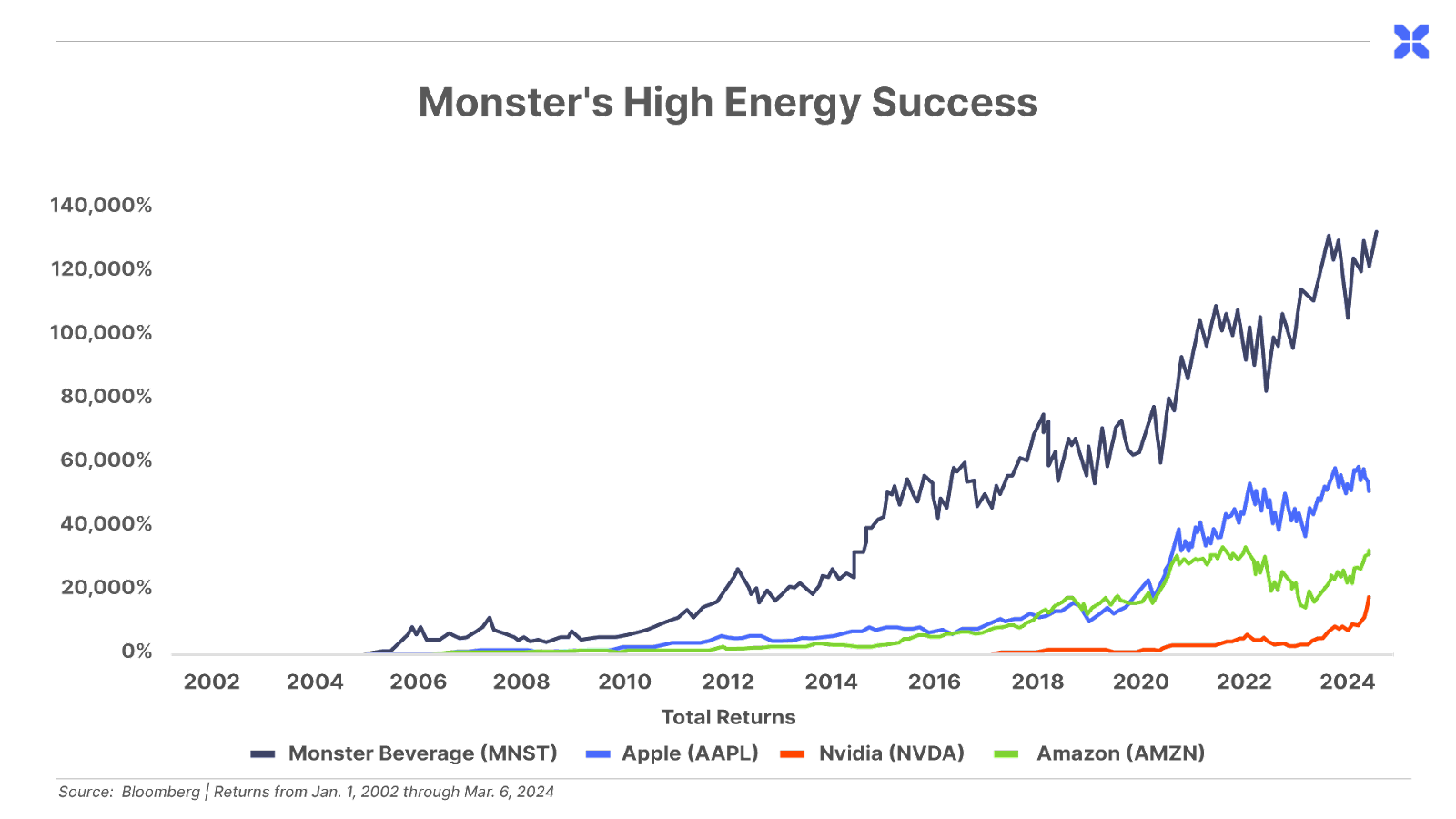

Big profit margins attracted countless imitators over the last three decades. All failed to make a meaningful dent in Red Bull’s dominant market share – until Monster Energy arrived in 2002. Like Red Bull, Monster outsourced bottling and distribution and focused solely on marketing and brand building. This made Monster Beverage (MNST) one of the best-performing stocks of all time. Since 2002, the shares have generated an incredible 132,200% return – outperforming tech giants like Apple, Nvidia, and Amazon, which themselves have been outshining the market.

Even investors who did not buy shares until Monster broke the billion-dollar annual sales barrier in Q3 2008 (demand for energy drinks continued growing through the 2008 Great Financial Crisis) have still generated a market-crushing 2,047% total return since then. That compares with a 493% return in the S&P 500 over the same period.

Today, that same opportunity has presented itself. For only the third time in history, a new energy drink has surpassed the billion-dollar mark in annual sales in the U.S.

But there’s one key difference this time around that could propel this brand beyond what both Monster and Red Bull achieved.

You see, Monster’s success came from following the Red Bull playbook, and thus it took market share from the same target audience. This new brand is stealing market share from its two larger rivals, while also opening up the energy-drink category to a massive new consumer cohort – one that its predecessors purposefully ignored.

And it’s created another opportunity for Red Bull- and Monster-style shareholder returns.

Let’s get started…

Supercharging the Energy-Drink Market

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.