Using Finance Tricks To Support Its Share Price

Share Buybacks Are A Good Thing… But Not Always

| This is Porter & Co.’s The Big Secret on Wall Street, which we publish every Thursday at 4 pm ET. Once a month, we provide to our paid-up subscribers a full report on a stock recommendation, and also a monthly extensive review of the current portfolio… At the end of this week’s issue, paid-up subscribers can find our Top 3 “Best Buys,” three newly added portfolio picks that are at an attractive buy price. You can go here to see the full portfolio of The Big Secret. Every week in The Big Secret, we provide analysis for non-paid subscribers. If you’re not yet a subscriber, to access the full paid issue, the portfolio, and all of our Big Secret insights and recommendations, please click here. |

Would you take a salary cut from $375,000 to $55,000?

What about if this was back in 1981, where $375,000 was worth north of a million, in today’s dollars?

… what if it was Ronald Reagan who asked you?

For hedge fund exec John Shad, the choice was simple. His friend Ronnie needed him to chair the SEC (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission), and that was all that mattered… even though the 84% pay cut meant he’d now earn less than his daughter, who’d just graduated law school.

Forty-five years before Elon Musk’s team started “DOGE-ing” federal institutions, the newly-elected President Ronald Reagan brought in his own crackdown crew to unwind New Deal-era government excesses. There was a lot to untangle.

For the first time in SEC history, the body that regulates the stock market would be overseen by (shocker!) a businessman… an investment banker and mergers-and-acquisitions specialist, rather than a career politician.

It was a savvy move on Reagan’s part. Shad – a stickler for ethics, a fan of the 80-hour workweek, and a huge bargain at $55,000 – immediately gave the SEC a pro-transparency, anti-corruption, pro-business makeover.

In the days before the internet was the lungs of the global economy, Shad pioneered a computer platform called EDGAR (Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval) that made all SEC filings available for anyone to view. He cracked down on insider trading, imprisoning notorious white-collar criminal “Ivan The Terrible” Boesky. And he kicked out a flock of the 1980s version of “DEI hires” from the SEC, making it a point to promote entirely on merit.

Most notably, in 1982, he implemented Rule 10b-18 … the “safe harbor” ruling that made stock buybacks kosher for the first time since the rip-roaring 1920s…

Safe, Legal, And Not At All Unusual

Stock buybacks are when a company purchases its own shares and takes them off the market, thereby reducing share count. This essentially allows the company’s earnings “pie” to be split into fewer “slices,” thereby increasing the earnings per share (“EPS”), a key metric tracked by Wall Street analysts.

Used judiciously by a company with strong financials, buybacks are a legitimate way to return cash to shareholders (as well as a convenient way for those investors to receive a “dividend” without having to pay a tax on cash dividends).

President Franklin Roosevelt took a dim view of stock buybacks, which he considered “market manipulation.” He didn’t ban buybacks outright, but his Depression-era SEC heavily regulated the practice to the point that most companies just didn’t bother doing it.

But John Shad changed all that. Under Reagan’s business-friendly regime, companies could buy back their shares with much fewer restrictions – for instance, not purchasing more than 25% of the stock’s available trading volume in a day (for most stocks, an easy rule to stay on the right side of).

With some modifications, Shad’s “safe harbor” ruling is still in effect today… and still getting plenty of mileage. In 2025, companies in the S&P 500 are expected to buy back $1 trillion of shares, up 16% from 2024 and roughly 100% over the past 10 years.

These days – particularly among Reagan-haters – stock buybacks often get a bad rap, with folks like Senator Elizabeth Warren claiming that they produce an unsustainable “sugar high” for corporations, and that their only purpose is to line CEOs’ pockets. But the truth is, they’re just a tool that can be used for good or for ill.

In general, there are two good reasons a company might buy back its own shares.

The first is when a company’s management team – who should know the business better than anyone else – believes its shares are trading at a discount to their intrinsic value. Using excess cash to buy back shares in this scenario is as close to “free money” as you’re likely to find in the business world.

The second is when a company – typically a mature business in a saturated or declining market – no longer believes it can earn an adequate return by reinvesting its cash back into its business. Again, in this case, returning cash to shareholders can make a great deal of sense.

However, in recent years, buybacks have become popular for another, less favorable, reason. Companies have increasingly turned to stock buybacks to manufacture EPS growth in the face of slowing (or even falling) revenue and net income. And in many cases, they’ve been taking on massive amounts of debt to do so.

This kind of financial engineering is the downside of Shad’s safe-harbor ruling.

When businesses shrink their share count to artificially inflate their stock price, it seldom ends well.

And right now, we’re seeing this scenario play out in real-time with one of the last companies you might expect…

This Market Leader Has A Problem

Apple (AAPL) is one of the most extraordinary consumer brands in history. It has a special sauce of blending high-end technology with a stylish, easy-to-use interface. It’s also unparalleled in its ability to keep users inside its tech and operating ecosystem (ever tried to switch from a Mac to a PC… or from an iPhone to an Android… and keep all your files and music and photos? Exactly).

Apple has achieved the dream of any consumer brand: It makes you feel smarter just for owning its products.

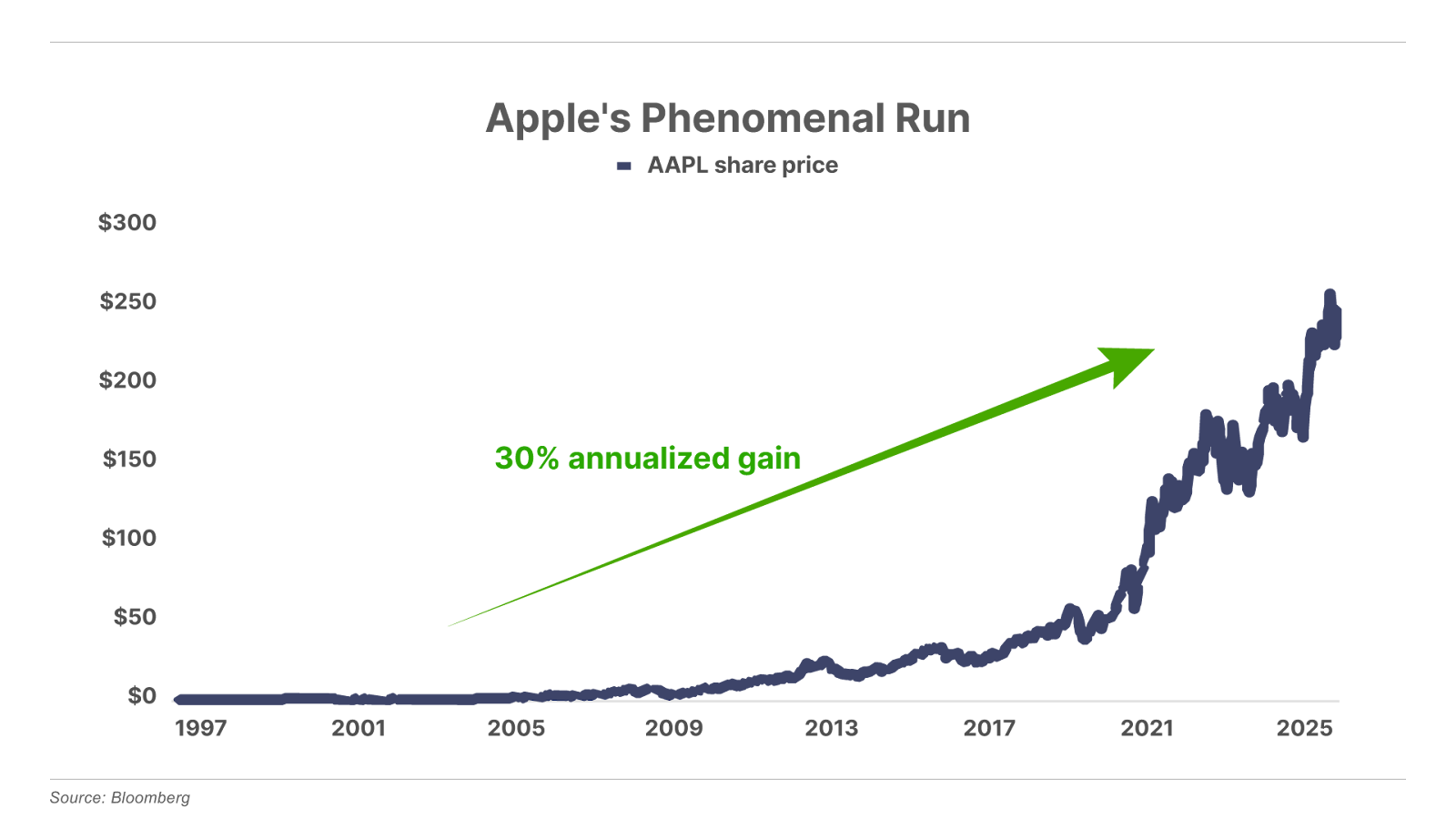

As a result, Apple has created immense wealth for its shareholders over the years. Shares are up an incredible 131,000% since the beginning of 1997, for an average annualized return of nearly 30%. So $1,000 invested in Apple in 1997 would be worth more than $1.3 million today (with dividends reinvested, that figure jumps to $1.6 million).

With some small bumps, it’s been a one-way road upward for Apple shares. The company’s market cap currently tops $3 trillion – that’s more than (depending on the day) any other publicly listed company, and more than the annual gross domestic product (“GDP”) of all but five countries.

Historically, it’s been a bad idea to bet against Apple. But today, we believe it’s a stock to avoid. And its growing reliance on share buybacks is a key reason why.

Apple’s Revenue Growth Has Stalled

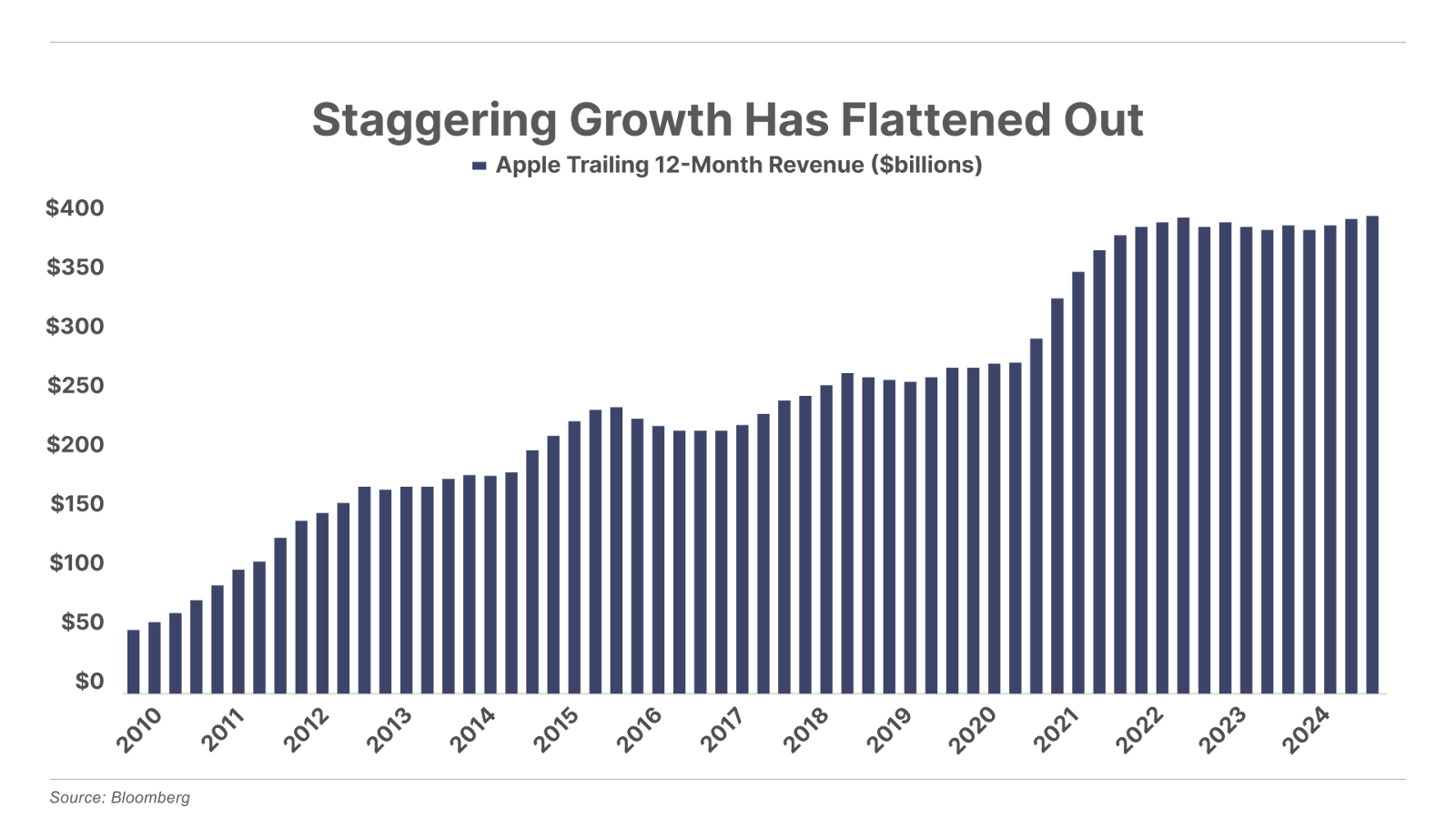

In the years following the Global Financial Crisis – fueled in large part by growing adoption of its then-new iPhone – Apple was able to grow at a remarkable clip. Between 2010 and 2016, the company increased revenue by an average of nearly 30% per year.

However, as Apple has become one of the largest companies in the world, its growth has naturally begun to slow. Over the past decade, revenue has grown at only 9% a year. And over the past three years, revenue essentially hasn’t grown at all.

Apple’s net income growth has also slowed. Yet, like an increasing number of other companies in recent years, Apple has continued to grow its EPS… thanks in large part to stock buybacks.

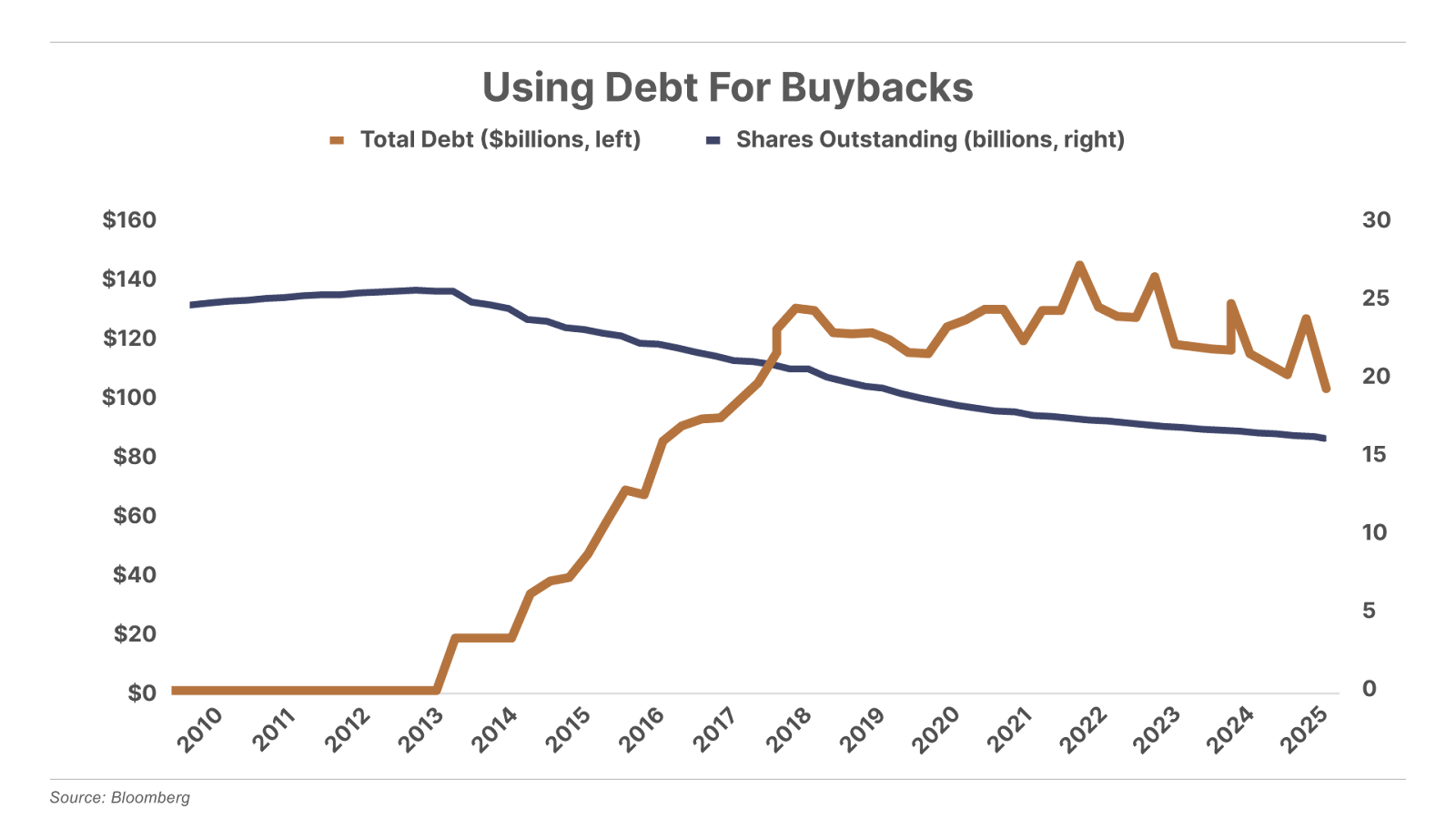

As you can see below, the number of AAPL shares outstanding has fallen by more than 40% since 2013. And much of these buybacks were financed by the $100 billion in debt the company has taken on over the same period.

Over the past several years – likely due to rising interest rates – Apple has used cash to fund these buybacks. Since 2019, the company’s massive cash hoard has been more than cut in half – from well over $100 billion to around $50 billion today.

Again, share buybacks aren’t necessarily a bad thing when used appropriately.

However, Apple’s reliance on this strategy has pushed its share price higher without a corresponding increase in revenue or net income. And that share-price growth is tough to justify without revenue and profit growth. (Apple already has superb margins – including a gross margin of 47% and an operating margin of nearly 30% – and improving them even further won’t be easy, particularly when prices are already high – see below).

As a result, that rising share price has led to stretched valuations…

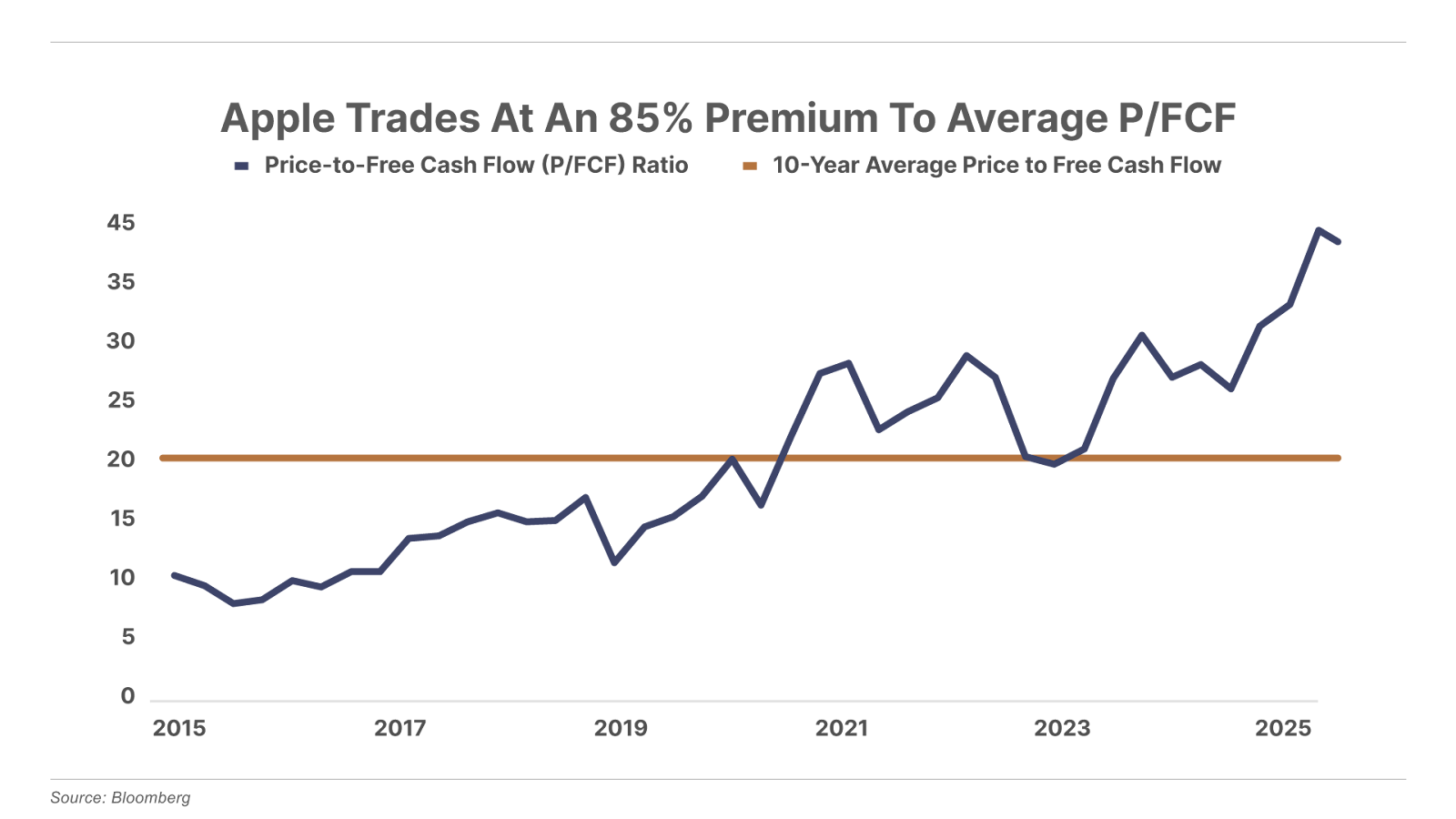

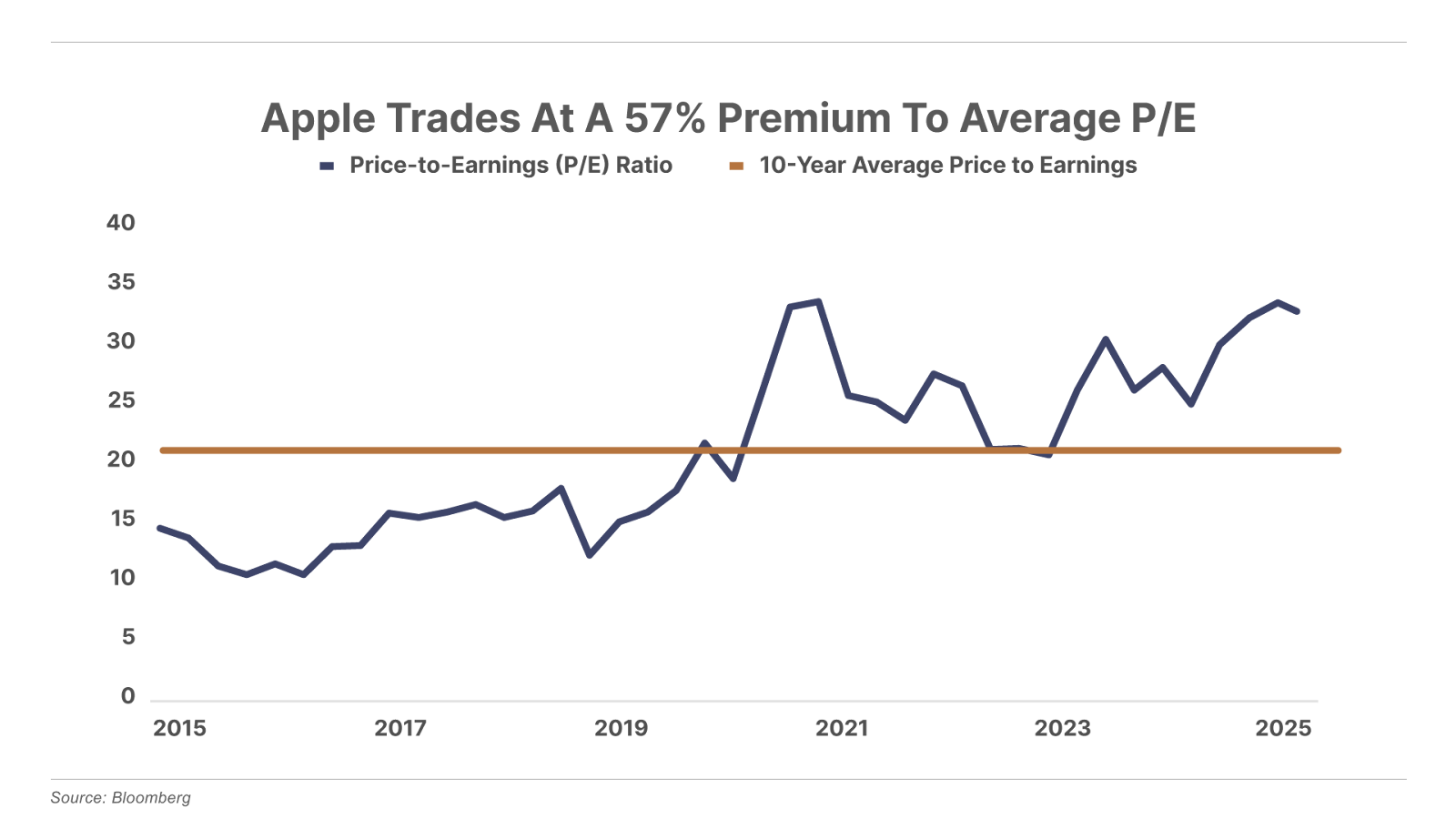

Apple Is The Most Expensive It’s Been In A Decade

As shown below, Apple is trading at big valuation premiums… at decade highs on a price-to-free cash flow basis, and within shouting distance of 10-year highs on a price-to-earnings basis.

If Apple were still growing rapidly, trading at these levels wouldn’t be a major concern for shareholders. But that is no longer the case, and buying a slow-growth mega cap at stretched valuations is not a great idea.

Worse, Apple’s continued buybacks at these lofty valuations mean each additional dollar it spends adds to the downside risk to its share price.

Barring a significant rebound in Apple’s revenue growth in coming quarters, its stock could decline significantly as the company returns to a more reasonable valuation. Based on the extremes above, shares could fall 50% or more.

However, it seems unlikely that any rebound in Apple’s growth rate, which would justify current valuations, is in the cards.

AI Isn’t Coming To The Rescue

Roughly 25% of Apple’s current market cap has been added in just the last year, following the company’s announcement of its upcoming artificial intelligence (“AI”) features.

The plan, it seems, was that AI gadgetry could be a trigger for an upgrade super cycle – that is, a reason for many of the roughly 1.4 billion iPhone users to get the newest model.

It doesn’t seem to have worked… The introduction of the iPhone 16 last September showed that Apple was nowhere near to bringing worthwhile AI features to its most important product (the iPhone accounts for around half of Apple’s total revenue).

When the company began to roll out these highly-touted AI features, reviews were mixed at best – with many users noting that the iPhone 16 is still well behind earlier offerings from competitors like Google and Samsung – which doesn’t bode well for the upgrade cycle. And it certainly hasn’t justified that $1 trillion in market cap gain of the past year – an amount equal to that of three Bank of Americas (BAC)… or 25 Ford Motors (F) – so far.

But this isn’t the only risk on the horizon…

The American Consumer Is Tapping Out

In recent months, a number of major consumer brands – including those that have traditionally been resilient to recession, like PepsiCo (PEP) and Procter & Gamble (PG) – have reported faltering demand and increased resistance to price hikes. And Americans now owe a record $1.21 trillion in credit card debt – so these problems are likely to get much worse if consumers run out of ways to spend.

Even assuming a full suite of AI features, $799 for a stripped-down, just-the-basics iPhone 16 (or as much as $1,599 for the Rolls Royce version) will be difficult for increasingly stretched American consumers – who account for roughly half of Apple’s total revenue – to justify… or to pay for.

If U.S. consumers choose to hold off on buying the newest-generation iPhone, Apple’s revenue will suffer even more.

Apple (Also) Has A China Problem

Or rather, two China problems.

First… China, which accounted for 17% of Apple’s total revenue in 2024 and is the company’s second-largest market, is turning away from the iPhone.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, Apple was the third-largest smartphone seller, with a market share of 15%, down from its peak of 25% just two years prior. Shipments in the fourth quarter were also down 25% year over year. Domestic competitors are well ahead of Apple in innovating and bringing AI to the market, with more appealing products.

Second… around 95% of all Apple products are manufactured in China. The bulk of the company’s far-flung supply chain is in China. For example, in the city of Zhengzhou in central China – also known as “iPhone City” – around 250,000 employees of Apple contractor Foxconn make most of the world’s iPhones, with inputs from a vast web of suppliers, many of them in the area.

The company has been trying to diversify – it has several production facilities in India, for example – but its heavy reliance on China can’t be resolved quickly. That means Apple is susceptible to being collateral damage in the evolving chilliness in geopolitical relations between China and the U.S.

Apple has a lot to lose in a trade war – which is looking increasingly likely under President Donald Trump’s efforts to impose tariffs – and this dynamic is unlikely to change anytime soon, given that a “China chill” is one of the few policies that is popular across the political spectrum in the U.S.

The Chinese government hasn’t yet interfered in Apple’s operations in the country to a meaningful degree, but it’s a threat that isn’t going away, and one that represents a serious risk for Apple shareholders.

The Bottom Line Is Clear

Apple will continue to be one of the world’s most valuable companies. Consumers will continue to use Apple products, likely for generations to come. So we certainly wouldn’t recommend shorting shares today.

But Apple’s lofty valuation simply isn’t supported by its current fundamentals. Even a routine correction could see its stock price fall by up to 50%.

That’s likely why legendary investor Warren Buffett has been selling. His firm Berkshire Hathaway, one of the largest holders of Apple, has reduced its massive stake by 600 million shares – or roughly 67% – since the end of 2023.

For now, there are far better investment opportunities for our capital.

Porter & Co.

Stevenson, MD

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.