Could you make a fortune buying into the AI boom today? Perhaps. We would rather own a world-beating business in a sector that is uniquely underappreciated by investors. In this issue, we recommend one of the highest-quality businesses ever created.

Lessons From America’s First Great Economic Boom and Bust

The Real Story of the American West Isn’t Paramount’s “1883”, It’s What Happened in 1887

Plus, One of the Very Best Businesses in the World is Now a Buy

Welcome to Porter & Co.! If you’re new here, thank you for joining us… and we look forward to getting to know you better. You can email your personal concierge, Lance, at this address, with any questions you might have about your subscription… The Big Secret on Wall Street… how to navigate our website… or anything else. You can also email our “Mailbag” address at any time: [email protected].

At the end of this issue, you’ll find our model portfolio, watchlist (which is also here), and Mailbag — as well as a “Best Buys” section, where we’ll briefly cover three portfolio names that we think you should consider buying first.

In addition to hosting The Big Secret on our website, it is also available as a downloadable PDF. Click here to download the full report.

Again… we’re excited that you’re with us…and we’re looking forward to a long and fulfilling relationship.

If you’re not a member and would like to learn more, click here.

By the early 1880s, Cheyenne, Wyoming was the wealthiest city in the world.

Flush with a never-ending stream of cash from their enormous ranches, the “Cattle Kings” established the Cheyenne Club in 1880. Designed to rival Denver’s Corkscrew Club, it was built to surpass the luxuries offered in London’s finest social clubs.

It had an indoor tennis court, served champagne at every meal, and offered the finest food from around the world – even fresh oysters.

The first “Cattle King” was John Wesley Iliff, a grocer who assembled a herd outside of Denver in 1861. His clients were local – he sold beef to the crews building the first western railroads and to the soldiers manning the Army’s forts built to protect them.

Demand for beef grew rapidly, especially after the Civil War ended in 1865. And Iliff made so much money supplying beef for government and railroad contracts, he was able to buy an enormous ranch – a stretch of land that ran 100 miles along the South Platte River in Colorado.

The great plains had previously been the domain of the buffalo. And their numbers were seemingly endless. In 1859 Luke Voorheese, an early settler, wrote that he’d traveled for 200 hundred miles through a single herd of buffalo between Colorado and Nebraska.

But, by the 1870s, buffalo hides were in huge demand for use as belts on steam engines in factories. And exterminating bison became the unofficial policy of the U.S. government. General Philip Sheridan’s strategy to control the Indians was to exterminate their food supply. The army gave away free ammunition to buffalo hunters. Most importantly, the Union Pacific Railroad cut the prairie in half, bringing thousands of hunters into the plains.

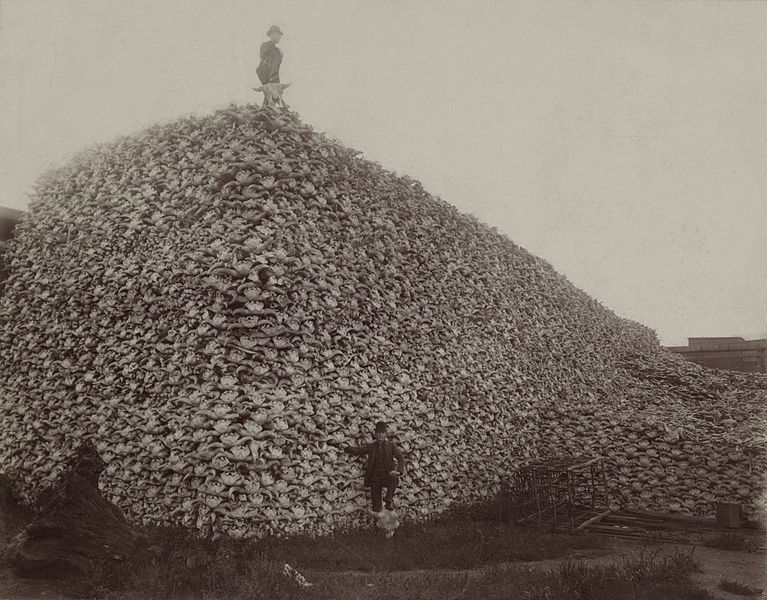

By the mid-1870s, piles of bones like this one littered the West.

Four years after the Union Pacific railroad was completed in 1869, the entire buffalo herd south of the Union Pacific line was gone. And by 1883, virtually every bison in the United States – some 20 million animals – had been slaughtered.

They were replaced by cattle.

In the spring of 1867, in the first of many fabled “cattle drives,” 35,000 head of cattle traveled the trails from Texas into the open ranges of Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, the Dakotas and Montana, searching for fresh pastures. Then 75,000 the next year. By 1871, more than half a million head of cattle a year were migrating northwards, into the plains where not long ago, “the buffalo roamed.”

In the two decades following the Civil War, a total of more than ten million head of cattle would be pushed into the northern plains, along with half a million horses and 50,000 cowboys.

In the spring of 1867, a 29-year old Illinois cattle broker, Joseph McCoy, figured he could reduce his costs by buying cattle “on the hoof” in the west and then shipping them, via specialized rail cars, to Chicago’s butchers. He pitched several railroads on the idea and was rejected by all of them, except the tiny Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad. With its backing, he built the first train depot for cattle on 250 acres outside of a tiny hamlet in Kansas called Abilene.

The depot could hold 1,000 head… but 35,000 head arrived in the summer and fall of 1867. And the next year, 70,000 head arrived for shipment to Chicago. By 1869, 140,000 head were shipped from McCoy’s depot.

Abilene became a boom town, virtually overnight. McCoy had created the West’s first cattle town.

Other entrepreneurs copied the success of McCoy’s cattle depot, building farther and farther north and west along the growing spurs of the railroads. In Kansas, depots were built at Ellsworth, Newton, Wichita, Caldwell, Hays, Dodge City, and Hunnewell. In Montana, at Miles City. And, most famously, in Wyoming at Cheyenne. By the early 1880s, this 3,000-person cattle town boasted the highest per capita income in the world (as well as a capitol dome plated with gold leaf).

By the late 1860s, the value of U.S. meat production reached $1.4 billion, or 20% of America’s entire GDP. Beef production in America doubled between 1870 and 1900.

The cattle boom created other lucrative spinoff industries, too… restaurants and meatpackers, for instance.

In 1860, Lorenzo Delmonico was operating restaurants in three locations, including his flagship in New York at 5th Avenue and 14th Street. Delmonico invented the menu, and his chef, Charles Ranhofer, dreamed up most of the dishes that would be featured on menus for the next 100 years, like eggs Benedict, lobster Newburg, Manhattan clam chowder, oysters Rockefeller and, in honor of the 1867 purchase of Alaska, baked Alaska. But the prime attraction at Delmonico’s was always beef.

By 1900, there were 1,304 meatpacking plants in the U.S. The five leading meatpacking corporations (Swift, Armour, Morris, Cudahy, and S&S) employed more workers than any other industry in the country. Meatpackers would remain the largest industry in America (by employment) until the automakers surpassed them in the 1920s.

But these facts alone don’t tell the whole story of how Cheyenne became the richest city in the world. It wasn’t only cowboys that built America’s economy after the Civil War. Or even the Cattle Kings.

The cattle boom and everything that followed was enabled by a radically disruptive new technology that dramatically increased the productivity of ranching: barbed wire.

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

Invented by three farmers at a county fair in DeKalb, Illinois in July 1874, barbed wire fences significantly boosted cattle’s odds of survival (until the meatpackers came calling) .

Separating bulls from each other (and protecting them from the other dangers of the open range) meant an 80% reduction in annual bull mortality. Barbed wire also meant that breeding could be accelerated and access to the best grasslands and watering holes could be controlled. And it reduced the need for cowboys to round up the cattle.

The economics were obvious: the bigger the ranch, the greater the returns from barbed wire fencing. Thus, demand for both ranch land and steel soared.

The leader in the barbed wire industry was John “Bet-a-Million” Gates, who, ignoring the patents of the original inventors, soon dominated the business through superior salesmanship. His American Steel and Wire grew like the Internet for a decade, with annual production exceeding one-million pounds after only two years.

In 1877, only three years after its invention, 12.8 million pounds of barbed wire were produced; 26.6 million pounds in 1878; 50.3 million pounds in 1880; and almost 100 million pounds by 1882.

The frenzy that followed will be familiar to anyone who remembers the Internet bubble of the 1990s. Seemingly endless demand for beef, amplified by the possibilities of the new barbed wire industry, created the impression of a “can’t lose” investment proposition.

Many of America’s richest families and individuals – Marshall Field, the Rockefellers, the Vanderbilts, the Flaglers, the Whitneys, the Seligmans, and the Ameses – invested heavily into cattle ranches. And the frenzy didn’t stop with the Yanks.

The cattle mania was also the first genuinely global investment mania.

In 1875, a New York beef wholesaler, Timothy Eastman, pioneered using blocks of ice, fans, and air-tight holds on steamships to keep freshly butchered beef refrigerated on all eight of the transatlantic steamship lines. To market the beef, he delivered a free load to Queen Victoria.

At the time, approximately 1,000 families owned virtually all of the land in the British Isles. Many of these estates were assembled by Henry VIII during the English Reformation, when he confiscated all of Church’s properties, and granted land and titles to his supporters. These estates generated much of the country’s wealth, before the industrial revolution, in the form of rents paid by tenant farmers.

However, in 1849, the growing wealth and power of the merchant class led to the repeal of the Corn Laws – tariffs that kept grain prices high in Britain. Soon grains imported from India and Argentina made farming unprofitable. The incomes of the aristocracy suffered, with ground rents falling by 75% between 1872 and 1890, leaving English and Scottish landowners desperate for higher yielding land. As Timothy Eastman’s shipment of American beef crossed the pond, rumors about the success of America’s cattle ranches became the talk of London – and imported American beef rapidly began to replace local beef as the premium meat.

In 1879, the British parliament sent two members, Clare Read and Albert Pell, to the American West to explore opportunities. What they reported back launched the biggest investment mania the world had yet seen. Read and Pell wrote “the acknowledged profits upon capital invested in cattle are 25% to 33% per year.” On the basis of that report, enormous amounts of capital flowed from Great Britain into the American West.

Between 1879 and 1888, the British formed 36 new companies and raised $45 million to invest in cattle, an amount of capital equal to 5% of British GDP. A comparably sized investment would equal $150 billion today.

When an exciting new industry meets a flood of capital from investors – who are willing to pay almost any price just to get in the game – it rarely ends well.

In A.I., The “Steaks” Are High

Today, a similar influx of enthusiastic capital is pouring into artificial intelligence.

In the American West, a new technology (barbed wire) converted the incredible abundance of the Great Plains into an enormous economic engine – beef – the demand for which was widely believed to be unlimited.

Today, a new technology (A.I.) promises to convert the abundance of microprocessing power and computer networks into useful intelligence, the demand for which is widely believed to be unlimited.

Like all manias, faith in the unbridled future is enough for investors to plunk down huge sums of capital.

Consider the case of Mobius AI – a new startup founded earlier this year by four former Google researchers. According to a recent New York Times article, the founders “weren’t sure what their product might be — just that it would involve A.I. technology that could generate its own photos and videos.”

Despite having little more than four employees and an AI dream, it was enough for two of the top U.S. venture capital (VC) firms, Andreessen Horowitz and Index Ventures, to fund the business at a $100 million valuation. Similar deals have been struck for other brand new start-up companies. More than $50 billion was invested into AI startups in 2022.

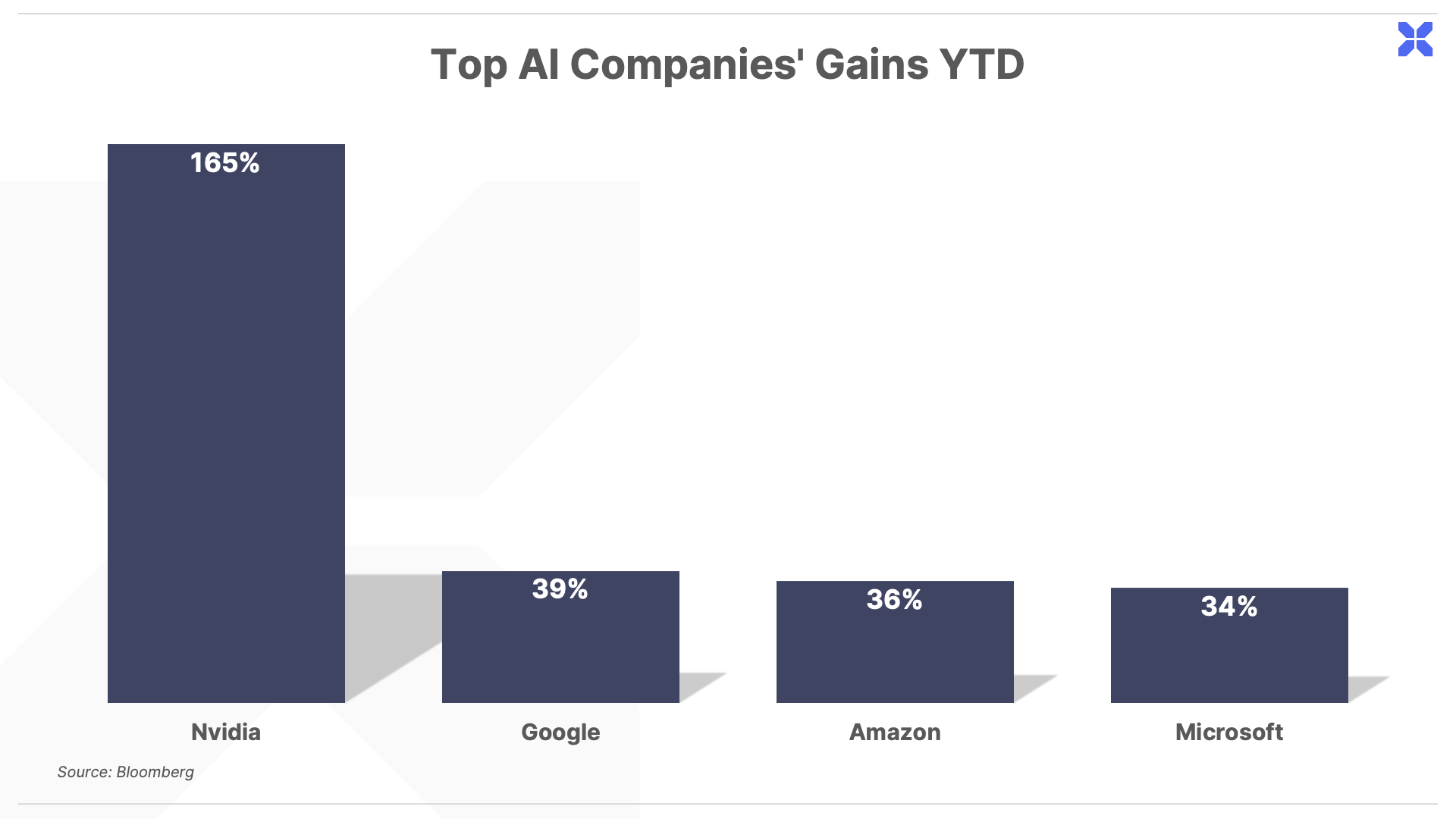

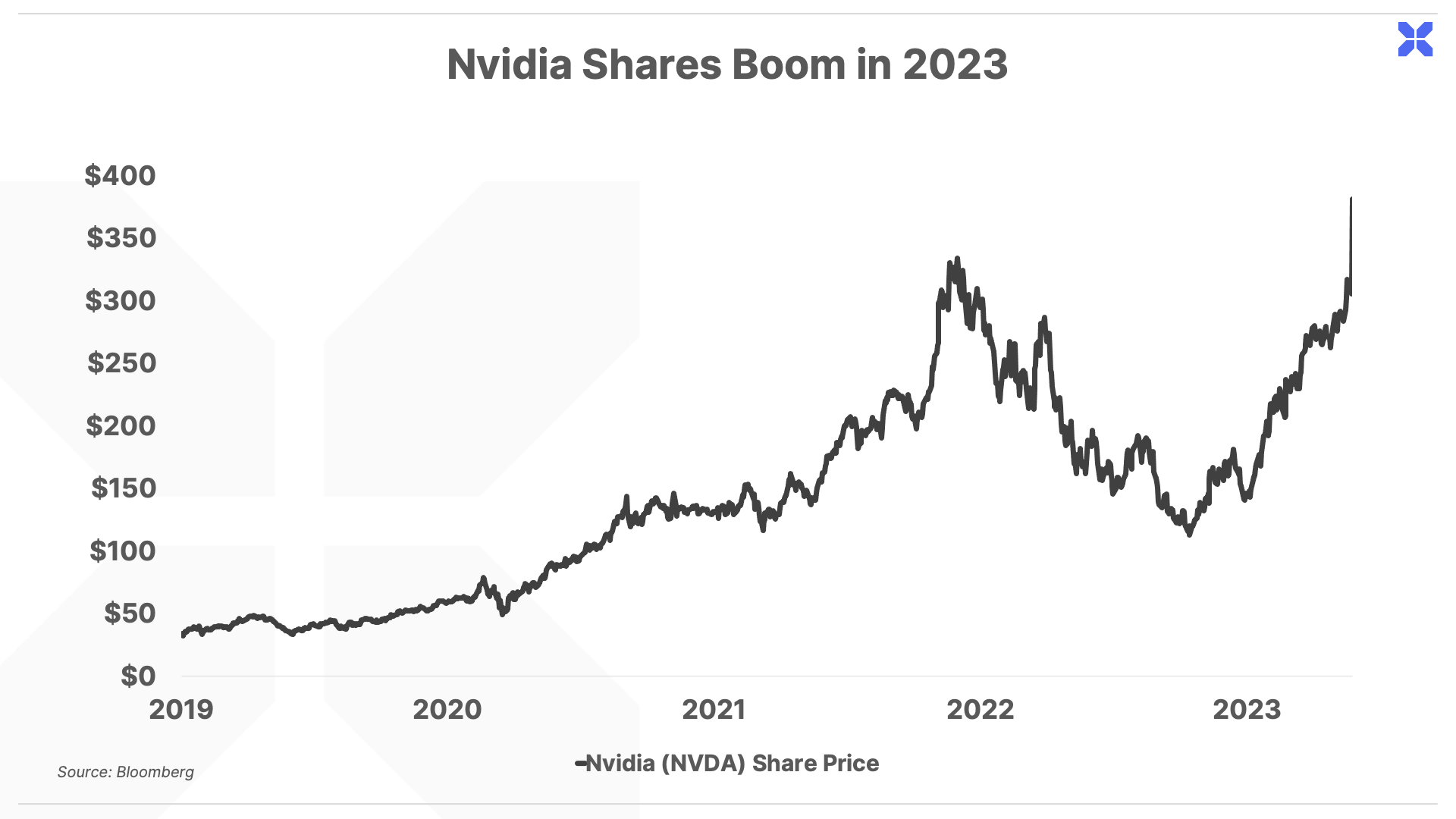

And far greater sums are being wagered in the public markets. Chipmaker Nvidia looks a lot like American Steel and Wire. Over the past five months, AI hype has fueled a stratospheric rise in Nvidia’s market capitalization from $350 billion in January to $950 billion today (including a one-day increase of $200 billion alone on May 25).

And Google, Microsoft, and Amazon look a lot like the best western ranches. The valuations for these companies have also gained hundreds of billions of dollars in value in recent months, with share prices routinely surging on any AI-related headlines.

But let’s not forget how the cattle boom ended.

“The Big Die-Up”

To go back to the plains… as capital poured into ranching and barbed wire began to privatize the endless prairie, there wasn’t enough good land for grazing. By 1886 the herds weren’t growing and, making matters worse, the price of beef was down about 20% from the year before.

Bubbles seem to attract pins. And the winter of 1886-1887 was the pin of the cattle boom.

No one had ever seen anything like it. In mid-January the snow started falling on the northern plains and it didn’t stop for ten days. The temperature fell to 28 below, to thirty below, to 46 below zero. To sixty degrees below zero. It was the coldest winter on record.

There was so much snow and so little grass left that the cows that didn’t freeze to death, starved to death waiting for spring to arrive.

When the spring finally came, there were hardly any cows left. The cowboys, with so few cows to round up, called the winter the “Big Die-Up.” More than a million head of cattle died. And virtually every large cattle ranch was wiped out, with losses of up to 80% of their herds.

Historian Christopher Knowlton, in his book Cattle Kingdom, wrote:

“The deadly winter proceeded, almost biblical in its ferocity and duration, as though it had every intention of humbling and shaming anyone who had participated in the great cattle boom.”

In Colorado, the number of large-scale cattle companies was slashed from 58 in 1885 to just nine by 1888. In one telling example, the Poudre Livestock Company lost two-thirds of its herd.

Barbed wire was useless to keep out the snow. In most cases, investors in the boom lost everything.

Investors from Boston poured $2 million (roughly $6 billion today) into the Union Cattle Co., in 1883. Investors included the copper baron Alexander Agassiz, the stockbroker Henry Higginson (who founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra), and Quincy Adams Shaw, scion of the wealthiest family in Boston. The ranch, at its peak, held 60,000 head of cattle. It paid an annual 8% dividend for two years.

How? Not by selling cattle. Union Cattle bought at the peak, right before prices collapsed. Unbeknownst to its shareholders, the company borrowed $1.6 million to complete its land purchases and to pay the dividend.

After the Big Die-Up, it went bankrupt and was a total loss.

The same happened across the range, to virtually every ranch that was established during the boom.

The Swan Land & Cattle Co, for example. A joint-stock company founded in Scotland in 1883 with $3 million in capital (equivalent to almost $10 billion today) it was the largest in the West – a ranch the size of Connecticut. Somehow the company paid 20% annual dividends until it collapsed after The Big Die-Up. How? The manager, Alexander Swan, explained it this way: “In our business we are often compelled to do certain things which, to the inexperienced, seem a little crooked.”

The most famous victim of the cattle bubble was 28-year-old Theodore Roosevelt. Fleeing the grief of losing both his mother (typhoid) and his first wife (kidney failure) on the same day, Roosevelt moved to the Dakota Territory and established the Elkhorn Ranch in the summer of 1883. He went on to invest most of his family’s wealth ($80,000 – a quarter of a billion today) into cattle, with disastrous results.

In the aftermath of The Big Die-Up, Roosevelt wrote to his sister: “I wish I was sure I would lose no more than half the money I invested out here.” In all, Roosevelt would lose 75% of his herd and virtually all of his money.

How Not to Die

At Porter & Co. we have seen enough booms and busts to know that the real challenge investors face is survival, not underperformance. (For a reminder of how risky investing can be, just look at our recent recommendation of Icahn Enterprises.)

We have never seen a relatively wealthy person complain about their retirement because their portfolio has only averaged a 12% return over 20 years instead of a 14% return. But we have, unfortunately, seen that most retired people eventually suffer a catastrophic investment loss, resulting in a real decrease to their standard of living.

Our advice: eliminate that possibility by never investing in companies and sectors that have become swept up in speculative mania. Avoid risk like the plague, and you might survive.

Likewise, we believe the best way to produce great returns over the long term is to own the highest quality businesses in the world.

Could you make a fortune buying Nvidia today? Perhaps. Like the barbed wire purveyors during the 1800s cattle boom, Nvidia is the leading supplier of the critical infrastructure that promises to unleash an AI-driven productivity boom.

For now, business is booming. Earlier this week, Nvidia announced guidance for next quarter revenues to reach a record $11 billion, up 32% from its prior record of $8.3 billion in quarterly revenue. But investors are pricing in a bright future, with the stock price skyrocketing from $100 per share late last year to $390 today. Wall Street analysts currently expect Nvidia to generate $5.93 in earnings for 2024, meaning shares trade at an eye-watering 66x price-to-earnings multiple (compared with 18x for the S&P 500).

Nvidia is now priced for perfection – it must continue growing and executing flawlessly in order to provide current investors with further upside from its lofty valuation. But history shows that when speculative fervor prices assets for perfection, any stumble can leave investors “out in the cold.”

It was a freak snowstorm that decimated the cattle speculators in the 1880s. For a company like Nvidia, the potential threats range from competitors encroaching on its market share to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan – a growing geopolitical risk that could wipe out 25% of Nvidia’s business overnight.

Forecasting the future competitive landscape of an emergent technology, or pricing in geopolitical risk is difficult. In order to justify Nvidia’s current valuation, investors must grapple with a series of highly uncertain future scenarios.

We would rather own a world-beating business in a sector that is uniquely underappreciated by investors.

In that regard, we suggest studying and then owning one of the best businesses we have ever had the privilege to recommend to investors. It is, we would argue, one of the highest quality businesses ever created.

It’s also largely immune to speculative mania because, quite frankly, it is boring. No one is running out to snap up shares of this company… except the richest men in the world.

And there’s a very important reason to consider buying it now…

“A Money-Printing Machine ”

This content is only available for paid members.

If you are interested in joining Porter & Co. either click the button below now or call our Customer Care team at 888-610-8895.